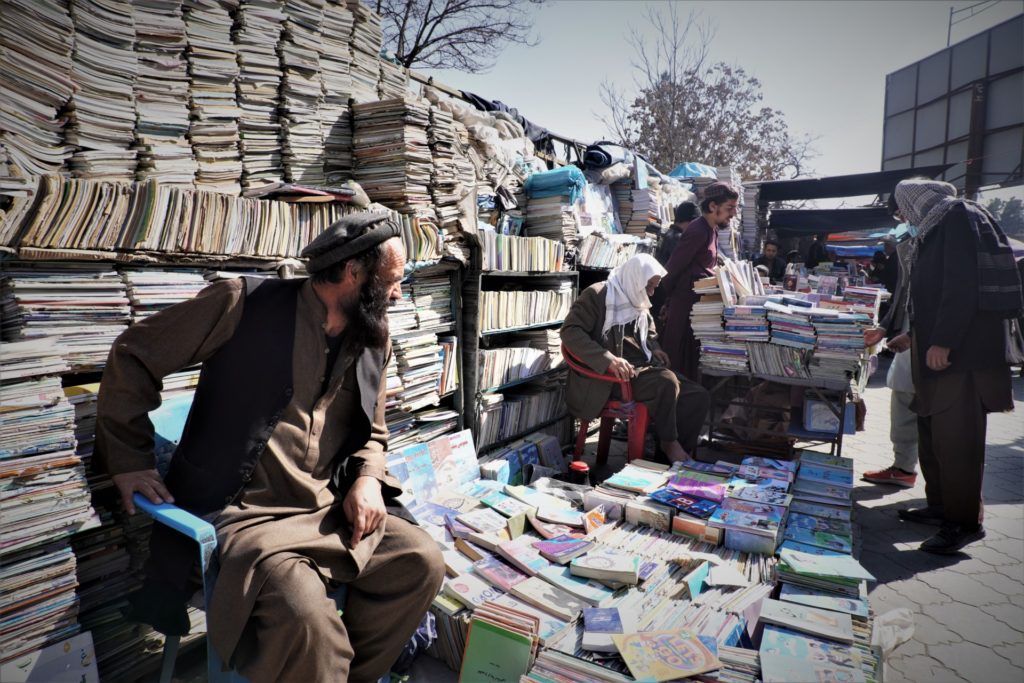

For the last 25 years, Shams ul-Haqq and Haji Sherazuddin have been selling books next to each other, near the Bagh-e-Omoomi bridge close to Kabul’s grand bazaar. One is a former communist, the other a former mujahid. Both have witnessed and participated in Afghanistan’s turbulent history over the past half century. They have seen the rise and fall of regimes and today sell books about the men who made and unmade them.

Shams is in his 60s, with a white beard. He sells political biographies and history books. On his shelves lie volumes that describe the very history he has lived through. A biography of the mujahideen commander Ahmad Shah Massoud sits beside one of the country’s last communist dictators, Dr. Mohammad Najibullah. Farther down the shelf is a biography of Mohammad Zahir Shah, the country’s last king, who in his later years came to be known nostalgically as Baba-ye Mellat (Father of the Nation). The choice of foreign biographies hints at the country’s eclectic political sensibilities. Farsi and Pashto translations of Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” lie next to a copy of Che Guevara’s “Bolivian Diary.” Some of the books are in English.

“Most of these men and their ideologies destroyed our country,” says Shams. “However, fewer people buy these books these days.”

Sherazuddin has sold textbooks from the start.

It was during the Taliban era that the two set up shop next to each other in the bazaar. Back then, both men received their books from Iranian and Pakistani distributors. Today, most books are printed in Afghanistan. During the Taliban era, book sales were restricted. “Although controls only happened occasionally, the Taliban obviously did not like books about secularism, socialism, or communism, and Iranian books, too, were unpopular because of their Shiite state ideology,” Sherazuddin recalls. Books about the Muslim Brotherhood and their ideology were also banned.

Most of their customers are young Afghans, mainly students. “Unlike the past, there are many schools and universities in today’s Kabul,” says Shams. “We benefit from that.” Other customers are known intellectuals or former politicians and military officials. Thanks to their demands, he earns around 500-600 afghani each day ($6-7) with which he can feed his family of 10. His sons sometimes help him run his open-air shop.

Unsurprisingly, the two booksellers at first did not get along. “He took the place next to me by force, typical mujahideen style,” Shams chuckles. “It’s fate that we, two former enemies, ended up here together. If we can make peace, so can other Afghans,” he adds.

During the 1980s, Shams was a reconnaissance officer in the Afghan communist regime’s air force. Though he wasn’t a member of the party, he still holds a favorable view of the Saur Revolution, the April 1978 communist coup. “Call it whatever you want, coup or revolution, but I can confirm that many young people in Kabul supported it. I grew up amongst them,” he says.

As a young urbanite, he believed that true progress could only come through fundamental change. Like many Kabulis, he was not satisfied with the policies of President Mohammad Daoud Khan, who had come to power in 1973 after toppling his cousin King Mohammad Zahir Shah in a bloodless coup. Daoud’s rule alienated both Islamists and communists, who were imprisoned in large numbers.

After Daoud’s murder, the communist reign of terror began. Many politicians, intellectuals, activists, writers, and religious figures were arrested and killed. Noor Mohammad Taraki, Afghanistan’s first communist dictator, pronounced that “all enemies of the revolution” needed to be executed, as once dictated “by Lenin himself.” After Taraki was killed by his protege, Hafizullah Amin, things only became worse. Detentions and executions increased. Finally, during Christmas 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, toppling Amin and replacing him with the more pliant Babrak Karmal.

“At first, it was not that different than in 2001, when the Americans and their allies entered Afghanistan,” says Shams. “A lot of people in Kabul were happy that someone intervened to end the mess.” But during the 10-year Soviet occupation, the situation deteriorated. While Karmal and the Kremlin’s other clients ruled in Kabul, Soviet-led counterinsurgency operations devastated the countryside. The insurgency grew, and the mujahideen rebels received global support from rich Persian Gulf countries, Europe, the United States, and Pakistan.

“I did not like the mujahideen,” says Shams. “I believed the state propaganda. I thought they were the main problem, not the regime.” Later, like thousands of other communist functionaries, he changed sides. It was not uncommon in the 1980s for many to be working for the Kabul government while secretly holding a membership card for Hizb-e-Islami, the largest mujahideen faction, led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

Sherazuddin, originally from Kabul’s Chardee area, joined Harakat-e Inqilab-e Islami, the mujahideen faction led by Mawlawi Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi, when he was 17. After the Saur Revolution, several of his family members were imprisoned and executed, which forced Sherazuddin, like thousands of other Afghans, to take up arms. Sherazuddin soon developed a reputation as a tough fighter.

“I regarded the Afghans who were supporting the Soviets as traitors,” he says. “In my eyes, they were worse than the occupiers. But later I realized things were more complex and that we were all gears in a large machine. From that history, we have to learn.” Sherazuddin fought mainly in the southeastern provinces of Logar and Paktia, areas that would later also become centers of armed resistance to the U.S.-led occupation. Unlike him, many of his fellow fighters had never even seen the Afghan capital and believed that all its inhabitants were hedonistic apostates, living a desultory life of drink and debauchery. “Meanwhile,” says Sherazuddin, “many Kabulis thought we were heart-eating monsters who drank the blood of their victims.”

After the Red Army withdrew in 1989, the communist regime of Mohammad Najibullah remained in power, buttressed by Soviet military and economic aid and attended by Soviet advisers. Najibullah’s government survived three more years. The mujahideen conquered Kabul in 1992, and a civil war broke out among their factions for control of the capital. But many former rebels like Sherazuddin refused to participate in the fratricide and returned to their homes.

Shams calls his friend “a true mujahid” because of this. “It was a dark time for the people of Kabul,” he says. “And the crimes of the former mujahideen gave the Taliban the reason and opportunity to take over the country. Many people, including myself, welcomed them.” Shams senses a similar desire for order and security now. During recent weeks, bombings and targeted assassinations have increased throughout the country. The crime rate has risen. “The thieves are everywhere, and they’ll kill a person for a mobile phone and some money,” says Shams.

Like millions of Afghans, Shams faces an uncertain future. Some of his family and friends have already left the country. “I would leave myself if I had the means and opportunity,” he says. But there are other factors that make this option undesirable. Not far from his shop is the hotel used by the International Organization for Migration to house Afghan refugees who have been deported from Europe. “I remember how a young man killed himself in his room after he was forced to return,” Shams recalls. “Only after we saw his body did we learn what was going on in the hotel.”

Over a year ago, on Feb. 29, 2020, the Afghan Taliban signed a withdrawal agreement with the Trump administration in Doha, Qatar. The deal included a prisoner exchange between the Taliban and President Ashraf Ghani’s government, to be completed by March 10. Kabul refused on the basis that it was not a party to the agreement; the Taliban in turn ramped up their violence. The insurgents are no longer at war with the U.S.; they are mainly targeting fellow Afghans, many of whom join the security forces to escape poverty. Their prospects look bleak since the Taliban have warned that those who “helped the invaders” will be shown no mercy.

Meanwhile, the Afghan National Army and pro-government militias have intensified their operations and, like the Taliban, have shown little regard for civilian life. Last March, militiamen linked to the notorious CIA-backed Khost Protection Force killed at least 20 civilians, including infants, in southeastern Khost province. A few days later, in eastern Nangarhar, the 02 Unit, another militia under Langley’s control, massacred civilians in a raid. During 2020, the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan documented 8,820 civilian casualties (3,035 killed and 5,785 injured), a decrease in the number of civilian casualties by 15% compared to 2019. But a sense of foreboding prevails about what lies ahead once the Taliban and the Afghan National Army join mortal combat without foreign forces as a buffer.

When President Joe Biden took over the White House in January, many observers hoped that he would take a different approach to America’s longest war than his predecessor and extend the U.S. presence in the country. Their hopes were frustrated. The Biden administration has announced the withdrawal of all US troops but 650 by Sept. 11, 2021.

“We are doomed with them, but we are also doomed without them. That’s the mess we are in,” Shams says. Sherazuddin, however, has a different view. “They should leave our country alone. This is a Muslim land, and it will never accept foreign occupiers,” he says.

For months, Afghan negotiators from both sides have been stuck in peace talks. Yet often, it appears to the public that elitist politicians, warlords and their offspring, and now privileged Taliban leaders in Qatar are engaged in an elaborate pantomime.

“I don’t really believe in these talks. At the end, foreign powers will dictate what’s good and what’s bad for us,” Sherazuddin says with a sense of fatalism. The man who once participated in a jihad against the Soviets is also leery of the Taliban. “Afghans are dying every day. It’s truly difficult for me to say something about their jihad. I think we truly need peace now,” he says.

Shams, on the other hand, thinks that Afghans forget their own responsibility. “Many things lie in our hands. We have international forces in the country, but we still kill each other. This will likely continue after their withdrawal. It’s up to us to stop it,” he says. “If political leaders don’t use this important moment, they will become like all these men in my books. What we need are people who can open their minds to each other, as Sherazuddin and I did. That’s the only way we can rebuild Afghanistan.”