Early in the Arab Spring, I saved my first screenshot of a revolution banner from Syria. This was before it became necessary to mark banners with dates and locations. Two young boys pulled the white fabric taut between them, the stark black Arabic letters stating, “If the price of freedom is a shroud, then it is with me.” I was stunned by the courage of this gesture steeped in meaning and symbolism. That was 2011 – long before the symbolism wore off and became Syria’s destiny. Since then, hundreds of thousands of Syrian lives have ended in such shrouds. Though the price has been paid many times over, freedom is nowhere to be found.

The back-and-forth between shrouds and banners, death and words, fear and freedom, make the essence of the Syrian revolution. Two years ago, the legend of epic banner-making, Raed Fares, was himself shrouded in his hometown, Kafranbel. On Black Friday, Nov. 23, 2018, Raed was shot dead in his car along with his loyal friend, Hamoud al Junaid, most likely by extremists tied to the jihadist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

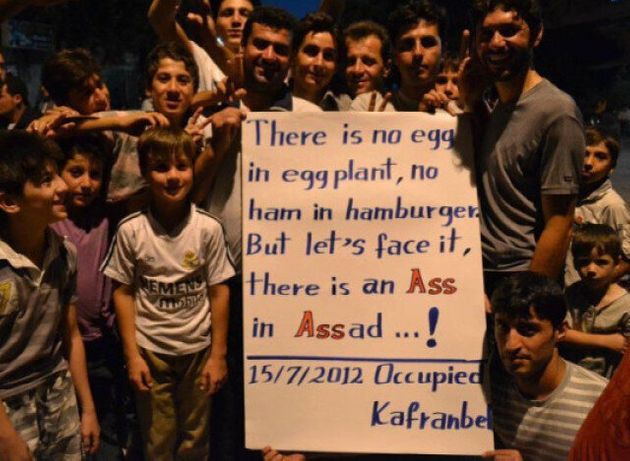

Kafranbel is one of the many sites of resistance that was virtually unknown before the revolution. When people from the small town in Idlib began to protest the Assad regime in April 2011, their weekly protests soon became known for witty banners and cartoons. Raed was behind the bold Arabic and English (and sometimes Russian) banners. His collaborator, Ahmad Jalal, drew the comical yet dark cartoons.

The blunt banners were like handmade tweets addressed to the world from the ground in Idlib. The Arabic banners were cutting, directed at the Assad regime, ISIS, the political opposition, the squabbling armed groups, and the suffering Syrian people.

No one escaped Raed’s brutal criticism: U.S. presidents, Russia, Iran, the United Nations – everyone who was witnessing the Syrian war and doing nothing to stop it. Many of the English banners extended sentiments of solidarity with other tragedies like the Boston Marathon bombing and social justice movements like Black Lives Matter. Some banners celebrated American holidays like Christmas, Thanksgiving, and even Black Friday. These earnest and often hilarious lines of broken, Google-translate English attempted to create bonds of empathy with the Syrian cause. A few of the banners went viral. Sometimes, like in Boston, people would make banners to send messages of solidarity back to Kafranbel.

Raed was a communications genius. He photographed the people carrying the banners in front of specific sites in the town, like a building with a bombed-out staircase, to document the progression of destruction. When the regime airstrikes and barrel bombs made it too dangerous to assemble in the open square, they retreated to narrow streets and shortened the protests.

He championed the values of the revolution and the rights of the Syrian people to live. And he favored one ideal above all: freedom.

As the years passed, Raed kept building his vision for a free Syria. He started Radio Fresh — a popular radio station for citizens in liberated areas that broadcasted the daily news, warned of airstrikes, and entertained with original comedy programs and music segments. Radio Fresh’s political defiance and secular perspective irked both the regime and Al-Nusra Front, al Qaeda’s former franchise in Syria. It was looted and destroyed by the Islamic extremists. Later, he founded the URB — Union of Revolutionary Bureaus — to organize the civil society efforts in Idlib. Raed survived two assassination attempts and a kidnapping by Al-Nusra related to his audacious activities. Before his killing, he was planning to produce a revolution comedy television series.

Raed’s Kafranbel represented a Syria that surpassed our dreams and imagination. He believed the revolution was a platform to build another future, far from the Assad family’s brutal authoritarian rule that has gripped the country for over four decades.

He used to tell me, “We can never go back to what was. The price has been too high, but we must keep going.” Like many Syrians witnessing the war from a distance, I felt my faith in the revolution waver as armed groups, extremists, and political opportunists marred the cause. However, Raed’s Kafranbel proved that our collective dream of a just and free Syria for all was not lost. As long as Syrians like him were speaking truth through their words and drawings, it was still possible.

As Syrians in the diaspora became friends with Raed, he embraced our renewed attachment to the country through the revolution. He made his town a home for us, both physically for those lucky enough to visit and virtually through social media. Every Friday morning, we devoured images of the new banners and spread them as far as we could, amplifying their message.

Years ago, I told Raed that one day we would build a Museum of Freedom in Kafranbel. We would display all the banners and posters inside. He laughed. I never imagined he would not be there to build it with us. It’s still hard to accept that invincible Raed is gone.

As the war grinds on and continues to take its heavy toll of death and displacement, I don’t understand how we can still be shocked by loss. However, Raed’s death has taken more space, needs more processing and reflection. His loss represents much more than one person’s tragic death. We lost the essence that he brought to the revolution: tenacity and joy. That unwavering belief that despite the despair that is Syria, we could still fight with our words, voices, jokes, wit, and our defiant laughter. With his death, we lost what could have – what should have – been.

There are so many uncountable, unmeasurable things that this brutal war has stolen from us. We did not account for the loss of possibility.

Raed was known for saying that “the revolution is an idea, and ideas cannot be killed.” Inspiring to many, but not helpful when the people behind the ideas can, in fact, be killed and their deaths send those left behind reeling.

Two years after losing Raed, we are in an extended Arab Autumn. He would have loved watching the irreverent, joyful protests in Lebanon last year. I imagine him chanting and cursing along with the united demonstrators. He would have cheered on the awe-inspiring and fearless revolutionaries in Iraq. He would have championed the spark of popular global movements against corruption and oppression. He would have made glorious banners that celebrated all those who called for freedom and dignity. He would have mourned George Floyd, been crushed over the Beirut blast, and led pandemic protests. And today, he would have been composing devastatingly funny banners about Donald Trump.

Raed’s sharp sarcasm would have called out the hypocrisies as well: the world’s silence over the destruction of Idlib over the past two years by regime and Russian airstrikes, in contrast to the massive outcry in response to the U.S. pullout from northeastern Syria; Trump’s gloating over the killings of Baghdadi and Soleimani while doing nothing to save civilian lives in Syria.

Today, Kafranbel is a ghost town, like many of the towns and villages in Idlib. The regime eventually bombed Radio Fresh’s headquarters before taking the town a couple months later. The few people who live there are the ones who could not flee. Raed’s family now lives in France. His son Mohamad often shares photos on Facebook: Raed as father, Raed as friend, Raed smoking, Raed playing his oud, Raed always smiling.

Scroll, stop, feel the pang of pain, snap, save. Repeat.

My phone now stores thousands of screenshots from the revolution and war. Almost a decade’s worth of photos of banners and dead people have slipped between the snapshots of my personal life. Sometimes I think of the two boys who lived for a few months on my screen. Where are they now? Are they still alive? Have they been displaced? Do they still believe in their banner?

As long as we are alive, we are all carrying our shrouds with us. Only the bravest among us will risk their lives to write the truth on them for the world to see. The most brilliant among us will write it in the form of a witty joke.