We live in a time of transformation in broader Arab-Israeli relations. Although peace between Israelis and Palestinians still seems far away, Arab states are increasingly not only coming to terms with Israel but also seeking a partnership with it. The United Arab Emirates and Bahrain have established official relations with Israel. Even Saudi Arabia, with its more delicate politics, is hinting at a potential alliance with the state. Egypt is a security partner of Israel, and Jordan even more so. Syria — at least the diminished version controlled by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad — stands apart.

Had recent history played out differently, might the Syrian president have entered the ranks of new Arab leaders making peace with Israel or even beaten them to it? Why did this not happen? Can it be ruled out now?

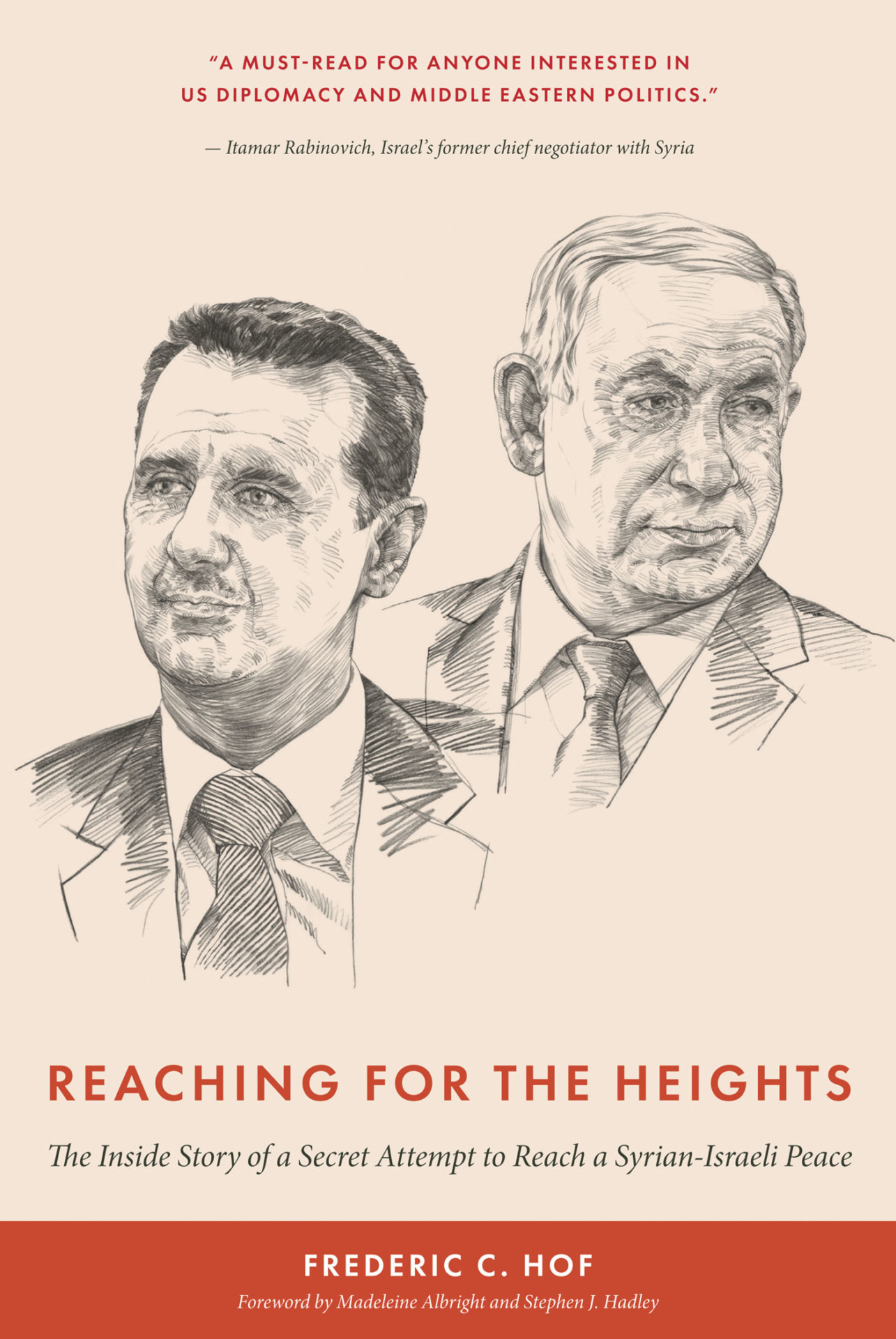

Ambassador Frederic C. Hof’s new book, “Reaching for the Heights: The Inside Story of a Secret Attempt to Reach a Syrian-Israeli Peace,” chronicles an ill understood but critical period of Middle East history. It focuses on secret negotiations, conducted and mediated by Hof himself, between Israel and Syria that came to an abrupt end with the latter’s collapse into protest, repression and finally civil war. The Israeli-Syrian peace track is often overshadowed by the Israeli-Palestinian one, but Hof’s account makes a strong case that peace between Syria and Israel deserved all the energy and attention he committed to it between 2009 and 2011.

New Lines sat down with the ambassador to discuss his experiences as a mediator in the secret negotiations between Israel and Syria.

New Lines: What drove you to commit all this effort in pursuit of an Israeli-Syrian peace, especially as the Israeli-Palestinian track is usually the centerpiece of Arab-Israeli peace talks?

Frederic C. Hof: By the time I was sworn in at the State Department in April 2009, Special Envoy George Mitchell already had in place his strategy for the Israeli-Palestinian track, and he had already assembled a talented team to support him. When I arrived, nothing comparable had been set up to address the Syria-Israel or Israel-Lebanon tracks.

The administration was verbally committed to “comprehensive peace,” but Mitchell’s time and resources seemed to be going exclusively into Palestinian-Israeli peacemaking. And why not? It was, and still is, the centerpiece of the Arab-Israeli peace process. But I believed that peace between Israel and its two northern neighbors would yield important dividends for the security of the U.S. It was inconceivable to me that Syria could be at peace with Israel while supporting Hezbollah in Lebanon and collaborating with Iran throughout the region.

I thought from the beginning that Syria’s strategic realignment — which would include Lebanon — would be the price it would have to pay for recovering land lost to Israel in 1967.

NL: Up to then, why do you think there was no peace between Israel and Syria over the decades? After all, the United States had tried to woo the elder [President Hafez al-]Assad to a peace track as well. Was Bashar different?

FCH: There were strong U.S. efforts in the 1990s to broker Syria-Israel peace. They fell short mainly because neither side was ever convinced that the other side was serious about wanting peace and ready to do what it would take to bring it about. The negotiations centered on the terms and conditions for the phased return to Syria of all territory it lost to Israel during the 1967 June War. But “all territory” was never defined by U.S. mediators or agreed to by the parties.

Hafez went to his death convinced that Israel would never negotiate the terms and conditions of complete Israeli withdrawal to the “line of June 4, 1967,” the unmarked line separating Syrian and Israeli forces in the Jordan Valley before war broke out. Multiple Israeli leaders convinced themselves that Hafez, who refused to charm the Israeli public like Anwar Sadat, was not ready for peace. During my mediation, however, serious progress was being made in convincing each side of the seriousness of the other. But then it all came crashing down starting in mid-March 2011.

NL: You mention that Washington, whose support you took for granted, played a more complicated role than that of unconditional backer. Can you explain how this affected your mission?

FCH: U.S. President Barack Obama stated early in his administration that he was committed to seeking comprehensive Arab-Israeli peace. Palestinian-Israeli peace was considered by the president and his team to be the centerpiece of peace diplomacy led by Mitchell. I accepted fully the primacy of the Israeli-Palestinian track while assuming the president to be also supportive of efforts to broker Israel-Syria and Israel-Lebanon peace. Mitchell’s efforts completely overshadowed mine, a condition that initially worked very much to my advantage.

Where Mitchell was, over time, subjected to ever-increasing interagency review and micromanagement, I was, relatively speaking, a free agent enjoying White House cover in the person of Dennis Ross, my eventual mediation partner. It was only when I reported significant progress after meetings with Bashar and [then-prime minister] Benjamin Netanyahu in early March 2011 that I began to fear that the White House was not prepared for success on the Israel-Syria front. Not only was there no response to an apparent breakthrough, but when Syrian violence began in mid-March, there was also no attempt by Obama to reach out personally to Bashar to try to stop the violence and preserve a promising peace mediation.

NL: How did this experience change your view of U.S. power and influence, especially U.S. diplomacy in the face of complicated challenges? You spent a considerable amount of time with Bashar, who of course would later become a war criminal and mass murderer. What was your impression of him at the time, personally and politically?

FCH: My experience reinforced something I thought I already knew: Diplomatic objectives must fully reflect the desires and priorities of the president. I took for granted Obama’s commitment to comprehensive peace without the benefit of due diligence — a major error on my part. As for Bashar, there was nothing in my encounters with him that suggested to me I was dealing with someone prone to mass murder and crimes against humanity. I knew, of course, that Syria was a police state and Bashar was the chief of police. But in meetings with Mitchell and me, he was invariably polite and engaging. I think the onetime chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, John Kerry, believed he had a solid relationship of trust and confidence with Bashar. Bashar, however, consistently lied to Mitchell and Kerry about Syria’s support for Hezbollah. He did not do so in my private meeting with him in February 2011. But he did assert in that meeting that Iran and Hezbollah would readily accept Syria-Israel peace, even though peace would require Syria to liquidate its military relationships with both, and Syria would pressure Lebanon to make peace with Israel, thereby putting Hezbollah out of its “resistance” game. I do not know if he was lying — hoping perhaps that Israel would bolt from the mediation at some point, leaving him blameless — or if he truly believed Iran and Hezbollah would be content to take a decisive beating lying down.

NL: How close do you believe we got to reaching peace between Syria and Israel?

FCH: Although I believe a genuine opportunity was missed, it’s impossible to say. Bashar had explicitly acknowledged that peace with Israel would have two essential elements: Syria’s strategic reorientation away from Iran, Hezbollah and Hamas; and Syria’s full recovery of all land lost to Israel in June 1967. Netanyahu acknowledged the territorial price Israel would have to pay and had authorized his team to work with me to define exactly the line of June 4, 1967. Both sides protected the confidentiality of the effort, and both sides gave every indication of seriousness.

Bashar’s mid-March 2011 decision to authorize violent responses to peaceful protesters stalled the mediation and — as the violence continued — killed it. Even if Bashar had acted reasonably and had convinced his constituents of his good intentions, no one on the U.S. team would have been booking tickets for a Rose Garden signing and handshake. There was still a lot of detailed work to be done. Either of the leaders might have flinched. Netanyahu might eventually have sensed political peril in giving up occupied territory. Bashar might eventually have feared assassination at the hands of Iran and Hezbollah. Still, the foundation seemed to be set. Territorial issues seemed to come down to where a boundary line would be drawn in relation to the upper course of the Jordan River flowing into the Sea of Galilee. Bashar had committed verbally to full strategic realignment in return for the phased return of all occupied territory.

Perhaps what should have worried me the most was whether the U.S. would have played the role of guarantor effectively. Having witnessed the White House second-guess and hobble Mitchell, I wonder what would have happened to the Israel-Syria track if Bashar had permitted the process to continue.

NL: Your book makes repeated reference to the so-called deposit, a mechanism employed in negotiations with the Israelis and Arabs. What is the “deposit,” and what role has it played in Arab-Israeli negotiations?

FCH: The “deposit” — originally called the “pocket” — is specifically applicable to the Syria-Israel track of the peace process. In 1993, Hafez made it clear to the new Clinton administration that he would negotiate peace with Israel only if it were clear what the negotiations would be about: the terms and conditions for full Syrian recovery of all land lost to Israel during the 1967 June War, meaning the Golan Heights and everything in the Jordan Valley to the “line of June 4, 1967.” In the absence of direct talks with Israeli officials, Hafez told his American interlocutors that his condition about the subject of negotiations would be met if Israel deposited its acceptance of that condition with the U.S. In trying to explain the deposit to an Israeli politician interested in cars, I said that Hafez was interested only in negotiating the price of a gold-plated Lexus; he was not interested in a Fiat or a Chevy. He wanted 100% of lost territory returned, nothing less. Successive Israeli prime ministers were reluctant to make the deposit. They feared that its public exposure would be characterized by political opponents as agreeing to a Syrian “precondition”: The return to Syria of all land occupied in June 1967. Still, Secretary of State Warren Christopher was able to report to Hafez in 1993 that he had the deposit from Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin. After a timeout caused by the Israel-PLO Oslo Agreement, Syria-Israel talks facilitated by the U.S. took place between 1994 and 1996. Syria assumed the deposit was in the pocket of U.S. President Bill Clinton. Ultimately, the deposit was nullified during the Clinton-Assad Geneva summit of March 2000, when it became clear that agreement between the parties on the location of the line of June 4, 1967, did not exist.

NL: Your book goes into detail about the territorial and operational parameters of peace, specifically around territory captured from Syria in the 1967 war. This might seem like a naive question, but is the devil actually in the details? Do such things decide the success or failure of such major initiatives? Or are these things basically workable once there is genuine intent to reach an agreement?

FCH: My sense is that all the details could have been worked out to the mutual satisfaction of both sides if they remained convinced that the essential parameters of Syria-Israel peace — strategic realignment in exchange for full territorial recovery — were solid. There would have been, for sure, sharp debates over details. We were in the middle of one over where the boundary should run in relation to the upper Jordan River when the mediation ended because of Syrian state terror. No doubt there would have been disputes over security arrangements and the overall timing and sequencing of implementing obligations. Still, unlike the negotiations of the 1990s, a solid foundation was in place. The two sides articulated full understanding of what was required, and neither side had, as of mid-March 2011, flinched.

Reaching for the Heights:

The Inside Story of a Secret Attempt to Reach a Syrian-Israeli Peace

– By Frederic C. Hof

NL: When the Syrian regime moved to crush the uprising, what could have been done to try to save the negotiations, and Syria for that matter, during that pivotal moment? Why was it not tried?

FCH: It’s possible nothing could have been done to save mediation once Bashar authorized the use of deadly force against peaceful protesters. But we will never know for sure. My White House negotiating partner, Ross, urged Obama to reach out telephonically to Bashar to warn him that a promising peace mediation would end if the violence continued. The president declined to make the call. I suggested to Ross that I be authorized to seek another private meeting with Bashar, one in which I would deliver the message. Ross sought the requisite permission, but it was not granted. I’ve been told by people in positions who may have known that the White House feared the domestic political implications of reaching out to Bashar and that key U.S. officials believed that Bashar would be a prominent casualty of the Arab Spring anyway. No attempt was ever made to speak with him and give him a chance to preserve the peace mediation. Bashar may well have rejected any such message in any event. But we will never know.

NL: What concessions would each side need to make, and to what extent did Netanyahu and Bashar seem aware of the risks involved in making them?

FCH: Israel would have had to return to Syrian sovereignty, over time — perhaps three to five years — all territory it took from Syria during the 1967 June War. Syria would have had to liquidate all threats to the security of Israel arising from its territory and from its relationships with Iran, Hezbollah and Hamas. Both sides were fully aware of what was required. Neither side tried to redefine or scale back its side of the commitment ledger. Netanyahu was acutely aware of the risks inherent in returning territory to Syria. He knew he would pay a domestic political price and planned to submit any agreement with Syria to a referendum. He wanted Syria’s strategic reorientation to be genuine and measured carefully during Israel’s phased withdrawal. He wanted strong U.S. support, including a large military assistance package. Bashar downplayed the risks inherent in breaking militarily with Iran and requiring Lebanon to make peace with Israel, a step that would have ended Hezbollah’s armed status as the “Lebanese Resistance.” Although he seemed sincere in claiming that Iran and Hezbollah would respect Syria’s decision to make peace with Israel, I had strong doubts that those actors would passively accept being marginalized.

NL: Do you feel that this experience challenged any common beliefs about diplomacy and peacemaking? And about Israel and Syria for that matter? Perhaps inevitably there is a thread of regret that runs through some of your memoir. Obviously your efforts failed to achieve Syrian-Israeli peace, but what, if anything, could you have done differently?

FCH: I think I could have moved more quickly to get the parties to the point where they were in March 2011. If I had been able to have the key meetings with Bashar and Netanyahu months earlier, it’s possible that the prospect of peace would have been publicized by the spring of 2011, perhaps preventing protests and the violent governmental reaction in Syria. Moving more quickly would have required me to act much more independently than I did. Mitchell had been reluctant to authorize any private meetings between me and Netanyahu. Quite understandably, he wanted Netanyahu to remain focused on the Palestinian track. In the summer of 2010, Ross gave me the opportunity to have such a meeting. It should have happened much earlier, and I should have taken the initiative to make it happen. It also occurs to me in retrospect that I should have done more to convince key White House officials of the feasibility and desirability of Israel-Syria peace. Ross did his best in that regard, but it proved to be insufficient. The White House reacted with silence to the apparent breakthrough of late February/early March 2011. The president refused to reach out to Bashar personally to try to stop the violence and preserve the mediation. I should have done a better job of convincing the home team of the national security merits of Syria-Israel peace.

NL: We are accustomed to seeing the Israeli-Arab conflict as open-ended if not hopeless, yet there is more peace than ever between the two sides. The UAE, Bahrain and perhaps even Saudi Arabia want to join Jordan and Egypt as peace partners with Israel. They are trying to lure Bashar into the Arab fold away from Iran. It would be ironic if the destruction of Syria and its infiltration by Iran and its proxies might make peace more possible. The United States’ efforts were complicated by Bashar’s atrocities. Could states that are less concerned with such crimes and increasingly close to Israel be more successful at negotiating an Israeli-Syrian settlement?

FCH: The baseline requirement for any resumption of Syria-Israel peace negotiations would be legitimate governance in Syria; governance regarded by nearly all Syrians as right and proper. Bashar, his family and his entourage personify illegitimacy. They have no standing to speak for Syrians on matters of war and peace. Arab states seeking to normalize relations with a war criminal are deluding themselves if they think he can be weaned off dependency on Iran. And they are powerless to make him legitimate. Syria appears to be a long way from the advent of legitimate governance. By the time full political transition takes place, the Golan Heights may be fully integrated into Israel. A future Syrian government might have to contemplate normalization with Israel without any territorial dimension. Bashar may have irrevocably deeded the Golan Heights to Israel.