Fethi Bejaoui, an archaeologist, still remembers his disbelief as he walked through Sakher El Materi’s villa.

It was 2011, just a few weeks after the revolution that had deposed El Materi’s father-in-law —Tunisian President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali — and forced the dictator and several members of his family to flee the country in private jets and yachts to Italy, France, and the Persian Gulf.

It seemed the family never had a plan B. As they fled on the night of Jan. 14, they were seen frantically stuffing wads of U.S. dollars into suitcases and bars of gold into handbags. According to one report, a member of the family even tried to make a last-minute transfer of $2.9 million — which was denied. Never could they have imagined that one day they’d be exiled from Tunisia, caught off guard and unprepared, forced to abandon their sprawling palaces, villas, businesses, and everything in them. They had thought their dynasty would last forever, with El Materi poised to become Ben Ali’s successor.

When Bejaoui ventured deeper into the home that El Materi and his wife Nesrine Ben Ali shared in the coastal town of Hammamet, it was ghostly quiet. The infinity pool had gathered leaves and debris; expensive furniture and family photos had been left in their usual arrangement; the cage that had housed the couple’s pet tiger, “Pacha,” stood empty.

“It was enormous and palatial,” he recalls, 10 years later in his office nestled among the ruins of ancient Carthage. “Just like a museum.”

But it was what greeted Bejaoui as he entered the living room that left him speechless. Stone epitaphs and engravings from the 2nd and 5th centuries had been broken apart and crudely inserted into the wall above the fireplace. Two ancient Roman columns had been erected next to a large stove in the kitchen, providing ceiling support. A precious marble bust of a woman had been hollowed out to form a wash basin. Bejaoui, stunned by the flagrant abuse of irreplaceable heritage, struggled to hold back his tears.

“These objects had just been torn apart,” he says. “It was criminal. Once you tear a monument apart, it’s over, it’s finished. We will never know the stories behind these artifacts.”

This looting and destruction of priceless treasures was symbolic of the excesses of El Materi and the rest of the Ben Ali clan, one of the many ways in which they had wantonly helped themselves to much of Tunisia’s wealth. But the traces of the fortune they left behind turned out to be just the beginning; much of their money lay in the hundreds of properties and businesses the family had hoarded throughout the years or hidden in offshore bank accounts across the globe. These assets would prove to be much less visible, or retrievable, than the treasures Bejaoui found at the villa.

In 2018, El Materi’s villa was reportedly sold to an unnamed sports star for an “unimaginable” price. At the time, the villa was estimated to value $17.5 million. The money made from the sale of the villa was returned to the Tunisian state — as was to be the fate of many of the family’s near 500 properties.

While the excessive accumulation of wealth by the former dictator and his family indicates they sat atop the kleptocracy in Tunisia, they did not represent the entirety of the corrupt system that saw billions stolen from Tunisian coffers over the past decades. As various committees and commissions were created, stalled, and then reestablished to recover the assets stolen by the Ben Ali-Trabelsi clan, some have argued that the corrupt tendencies of the former regime endured and that endemic mismanagement has prevented the return of these assets to the state.

From the mid-1990s, the dictator and his family had amassed vast swaths of wealth through the Tunisian economy. The U.S. think tank Global Financial Integrity estimates that between 2000 and 2008, over $9 billion was lost to illicit financial activities and official government corruption. Meanwhile, many Tunisians struggled to find employment or provide a dignified life for themselves. In 2010, the unemployment rate among graduates was 23%. There were also gaping economic disparities between the coastal elites and the interior regions, with poverty rates in the latter almost four times higher than those in the rest of the country at the time of the revolution. The family’s ransacking of the economy was one of the main grievances that drew people out onto the streets in 2011, with many chanting “The Trabelsis have eaten the whole economy!”

Ten years on, many members of the Ben Ali-Trabelsi clan remain in exile, scattered across the world in Saudi Arabia, the Seychelles, and France. Some, like Leila Trabelsi’s nephew Imed, are in jail, while in-laws Slim Cheboub and Marouane Mabrouk, having either proved their innocence or made amends, have been allowed back to Tunisia. But the question that has dogged Tunisians for a decade remains — what happened to the money? Where is it hidden, and will Tunisians ever be able to recover what was stolen from them?

The answer is somewhat depressing. In the context of a global financial system that caters to and protects the very wealthy, it is unlikely Tunisia will ever get all the money back — estimated to be $17 billion by the Tunisian Association for Financial Transparency. But Tunisia could still get back part of it.

Today, with the country facing an ever-worsening economic crisis, experts argue that the asset recovery question has become even more urgent. When compared to Libyan ruler Moammar Gadhafi’s $150 billion, Ben Ali’s fortune may seem small, but to a country facing near bankruptcy, it’s substantial.

“It is more of a symbolic gesture, to get this money back. This is Tunisians’ money,” says Mouheb Garoui, founder of Tunisian anti-corruption NGO I-Watch. “But right now, every euro and dollar counts. We have never seen a crisis like this before.”

Since 2011, Tunisia has been plagued by sinking wages and growing joblessness, with unemployment rising to 18% amid the coronavirus pandemic. Tunisia’s 2021 budget forecasts borrowing needs at $7.2 billion, including $5 billion in foreign loans.

“Even $1 billion is meaningful,” says Jamel Ksibi, a Tunisian businessman who has managed several construction companies since the 1990s. “$1 billion would give employment to thousands and thousands of Tunisians. If we invested it in infrastructure or roads or flooding protection for example, that would transform regions and give employment.”

But as more time passes and the country’s crisis deepens, the likelihood of Tunisia ever recovering the stolen money wanes.

It is useful when examining Tunisia’s asset recovery strategy to first establish how the Ben Ali-Trabelsi clan operated and how exactly they became so wealthy. The clan consisted of Ben Ali and his wife Leila Trabelsi; Ben Ali’s children, both with Leila and with his first wife Naima Kefi, and their spouses; and the extended families of Ben Ali and Leila, including Leila’s notorious brother Belhassen and nephew Imed Trabelsi, accused of being the main drivers behind the family’s nefarious accumulation of wealth and seizure of property.

The Trabelsi family emerged in the mid-1990s, after Ben Ali’s marriage to Leila, just as Tunisia began its push toward greater privatization. The Trabelsis’ proximity to power gave them access to information about upcoming deals, and they would position themselves strategically. They would abuse their influence — and people’s fear of the regime — to secure these deals. In 2014, the World Bank released a report that found that the companies owned by the Ben Ali-Trabelsi clan made up 21% of private sector profits, despite only accounting for 3% of its output and 1% of its employment.

Researcher Mohamed-Dhia Hammami has mapped out the Ben Ali-Trabelsi networks using data on the companies confiscated after 2011. “Here you have an integrated, giant network at the center where you can find the most influential figures — Sakher El Materi, Belhassen Trabelsi, and many others,” he says, zooming in on a graphic that resembles a knotted spiderweb on his iPad. “However, you also find all of these individuals who are not connected to anyone but whose assets were confiscated because they had some form of relationship with the regime.”

Hammami explains that although there was no chain of command — those in the Ben Ali-Trabelsi network were not simply obeying the orders of Ben Ali — there existed a kind of social hierarchy. According to where they were positioned, some had more authority over others.

“The connections that matter are the ones between themselves: They were cooperating together for the accumulation of wealth. They constituted a community on their own.”

Ksibi, the businessman, remembers how the business climate began to sour as this community gained power.

“We started to notice — every year, every month — that their influence was expanding,” recalls Ksibi in an interview in his office in Tunis’ main business district. “Every sector started to be controlled. They started with imports, then tourism, then certain agriculture domains, even transport. The evolution was fast and intense.”

Ksibi says that in order to survive, one had to tread lightly and avoid confrontation with the interests of the family or their friends and associates. “We started to be afraid of becoming competitors, truly afraid, because at the time you risked years in prison for one misstep.”

“These were barriers that instilled real fear.”

Once the dictator and his family fled, these barriers melted away.

In February 2011, financial specialist Jean-Pierre Brun was part of a team from the Stolen Asset Recovery (StAR) initiative, a partnership between the World Bank and the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime, that traveled to Tunis to meet and offer assistance to the new government. Still in the throes of revolution, the city was on high alert. Gunshots and the sounds of armed conflict could be heard in the street outside their meeting room.

“As soon as the government changed, we were on the ground very quickly,” says Brun. “Efforts to recover the stolen assets were identified as one of the first priorities by authorities. … Expectations were very high.”

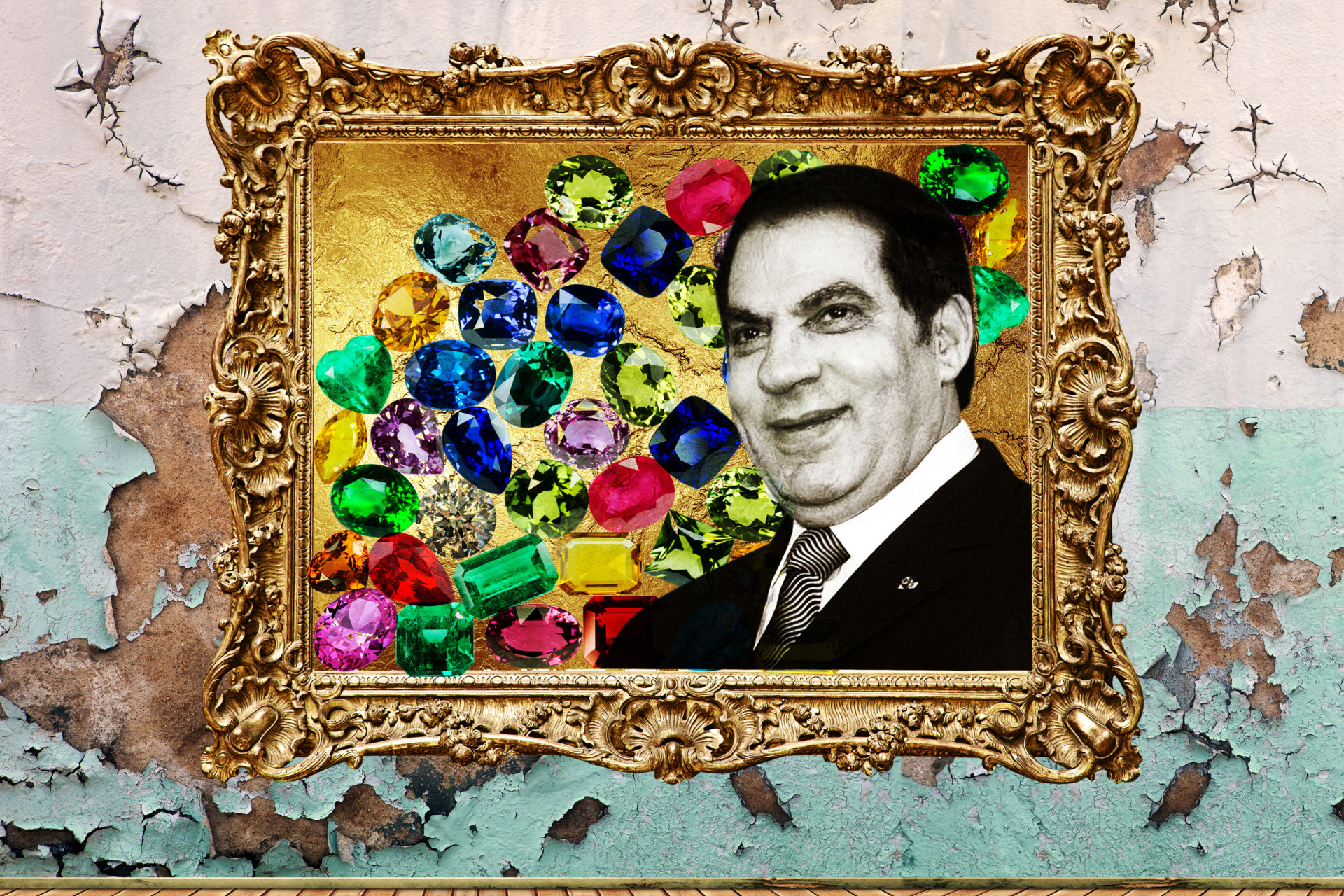

As news of the clan’s departure spread, the protestors demanded the restitution of the stolen assets. A strategy, led by the governor of Tunisia’s central bank, was quickly drawn up. International arrest warrants were issued for Ben Ali, Leila Trabelsi, and members of their family — the couple would later be tried in absentia on suspicion of corruption and sentenced to life in prison for theft and unlawful possession of cash and jewelry.

On March 14, 2011, a decree was issued by interim President Fouad Mebazaa that stated that all the assets of Ben Ali, Leila Trabelsi, and 112 other individuals from their close circle would be automatically confiscated. The new law decreed that all “movable and immovable property” — businesses, properties, cars, furniture, and other luxury items — that had been obtained after 1987, the year that Ben Ali came to power, would be considered illegal. Only inherited assets, or those obtained before 1987, were exempt. The onus was now on the family to prove their innocence.

A report on TV showed stern investigators revealing a hidden safe in the palace, filled to the brim with cash and jewels.

In the beginning there was tremendous optimism. Media crews were invited to Ben Ali’s colossal palace that rose above a high cliff at Sidi Dhrif in the northwest of Tunis and encouraged to show the world his jaw-dropping extravagance and greed. A report on TV showed stern investigators revealing a hidden safe in the palace, filled to the brim with cash and jewels. There were also public sales of thousands of their belongings, from Leila Trabelsi’s designer handbags and shoes to the family’s luxury cars, including bespoke Aston Martins and Mercedes that had never been driven, branded with their personal signatures.

Both the government and the public were eager to publicize the family’s wicked ways, hoping that the ill-gotten billions would be returned to the Tunisian state as quickly as possible.

“We told Tunisian authorities that in order to be successful they needed first to create a real task force, an interagency body, that would embody this political will,” says Brun. The result was the creation of Tunisia’s semi-independent National Asset Recovery Committee, made up of six different bodies composed of officials from the central bank, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Justice, and Ministry of State Domains and tasked with the identification and retrieval of the clan’s assets both in Tunisia and abroad. In 2014, the government would also form an independent tribunal with a four-year mandate — the Truth and Dignity Commission — that would carry out its own independent arbitrations and investigations. This commission’s remit was more reconciliatory and would encourage corrupt individuals to come forward voluntarily and make amends.

The strategy was twofold. There was first the question of the family’s domestic assets, which according to analysts made up the majority of the clan’s wealth. Businesses that were owned (in part or in full) by the Ben Ali-Trabelsi clan — such as French telecom company Orange, radio station Shems FM, or car dealership Ennakl Automobiles — were confiscated and essentially nationalized. The seized assets included 550 properties, 48 boats and yachts, 40 stock portfolios, 367 bank accounts, and approximately 400 enterprises, with an estimated value of $13 billion. El Materi’s business group Princesse El-Materi Holdings was nationalized and renamed Al Karama Holding: Formerly the masthead of El Materi’s corrupt dealings, it was now tasked with the management and resale of these companies on behalf of the state. In 2015, a similar fate was to befall a real estate company owned by Belhassen Trabelsi, “Gammarth Immobiliére,” which was handed the unenviable task of finding sufficiently wealthy buyers for the family’s grotesque palaces.

Then there was the question of the family’s money abroad. The EU was quick to impose sanctions on 48 members of the Ben Ali-Trabelsi family, while the Swiss government announced a 10-year freeze on 60 million Swiss francs ($65.6 million) it had identified in its banks. With almost no experience in asset recovery, nor the protocol or contacts in place for making such international requests, the new Tunisian authorities approached the matter in a manner that Brun charitably described as “a bit improvised.”

Just a few weeks after the collapse of the 23-year-old regime, Tunisia’s judiciary and ministries were in shock. With no prior surveillance of economic elites in place — Ben Ali’s 2003 anti-terrorism and money laundering law had not been properly implemented — they had to start from scratch. They drew up their own databases and research teams. Mutual legal assistance requests were launched haphazardly through embassies, often without prior communication or a clear outline of what evidence was needed. Tunisia’s Financial Intelligence Unit, newly charged with collecting data on suspicious transactions from financial institutions, was overwhelmed with information.

Despite this chaotic approach, there was initially a fast response from the international community. Apartments valuing between 20 million and 50 million euros ($24 million to $60 million) were identified in France, bank accounts in Switzerland, Lebanon, and Canada, and yachts and private jets in Italy and Spain.

There were, in the first few years, some small but meaningful wins. In April 2013, $28.8 million was confiscated from Leila Trabelsi’s bank account in Lebanon and transferred back to Tunisia, while the planes and yachts in which the family fled were returned to Tunisia from Switzerland, Spain, and Italy. “It’s not so frequently that in the first two or three years of an asset recovery action that generally lasts for years or decades, you have some preliminary successes like that,” says Brun.

However, in 2012, Tunisian President Moncef Marzouki gave a solemn address to a hall of delegates in Doha at the inaugural Arab Forum on Asset Recovery. While Marzouki expressed Tunisia’s continued resolve to recover stolen assets and to hold accountable those responsible for the corruption, he said that the government had faced some significant obstacles — notably, a lack of information about assets frozen in foreign jurisdictions and a slow response to mutual legal assistance requests.

Indeed, despite the enthusiasm and initial successes, the strategy had quickly become beset with problems, bogged down in mountains of paperwork and foreign jurisdictions’ complex and cumbersome legal requirements. To make matters worse, there was little cohesion between Tunisia’s multiple committees in their handling of the questions over assets. From the get-go, officials have since argued that Tunisia had neither the expertise nor the strength of resources to effectively tackle such problems.

When the national committee was liquidated in 2015, these problems multiplied.

Tunisia’s head of state litigation, Ali Abbes, was only appointed six months ago, but he talks with the weariness of someone who’s been on the job for much longer.

“When the strategy was conceived at the beginning, they didn’t think it would be so complex or that it would be so difficult to get a result,” he says. Optimism was such that the original committee’s mandate was limited to four years, he explains, with officials thinking it would be more straightforward to get the money back. In that time, the committee received a huge amount of documentation that needed careful investigation. “We still need more time as it’s extremely complex,” he sighs. Since 2015, Tunisia’s asset recovery strategy has seen few successes. In 2017, 3.5 million euros ($4.2 million) was returned from Switzerland — a small fraction of what remains. A recent article in Jeune Afrique estimated that so far, Tunisia has only been able to recover roughly $750 million from the resale of businesses through Al Karama Holding. In its final report, the Truth and Dignity Commission stated that it had managed to recuperate approximately $252 million through arbitration — Jeune Afrique however found that so far only $4.5 million had been deposited in the requisite account. This brings the total known amount recovered in the last 10 years to approximately $788 million, by my estimate, based on extensive reporting.

First, there was the problem of the money itself. One of the main challenges is that no one knows how much money they are actually looking for. The showy auctions of the family’s jewels and cars led to inflated estimates — the highest being $42 billion — which raised expectations and paved the way for disappointment. Garoui, meanwhile, says that most of the family’s assets were left in Tunisia and that the money stashed abroad “cannot reasonably be more than $1 to 1.5 billion.” What has so far been identified by foreign jurisdictions is, however, much, much lower. “Unless you find the assets, you are obliged to guess,” says Brun.

This guessing game stems from the loopholes and opacity within the global financial system — what British journalist and expert on kleptocracies Oliver Bullough has coined “Moneyland.”

“I call this new world Moneyland — Maltese passports, English libel, American privacy, Panamanian shell companies, Jersey trusts, Liechtenstein foundations, all add together to create a virtual space that is far greater than the sum of their parts,” writes Bullough in his 2018 book on the subject.

Much of the Ben Ali-Trabelsi money is likely camouflaged behind complex corporate structures, within shell companies or trust funds, making it impossible for investigators to trace the money. The family, though mostly in exile with supposedly most of their assets frozen, continue to live comfortably. While he sought asylum in Canada (which was eventually denied), Belhassen Trabelsi languished in a $5,000-a-month luxury apartment in the heart of Montreal. Local media reported that he had signed a $28,000 check for three months of school tuition for his children and paid thousands more for a security detail. Leila Trabelsi and her children, meanwhile, continue to live well in Saudi Arabia — where the largest portion of their wealth is said to be kept. Cooperation requests made by the Tunisian government to the Saudi authorities have gone ignored.

Offshore finance has changed everything, says Bullough. “Some people call shell companies getaway cars for dodgy money, but — when combined with the modern financial system — they’re more like magical teleporter boxes,” he writes. “If you steal money, you no longer have to hide it in a safe … instead, you stash it in your magic box, which spirits it away, out of the country, to any destination you choose.”

Once there, now hidden within multiple jurisdictions or corporate vehicles, the stolen money is very difficult if not impossible to get back, even if a corrupt regime collapses.

“The corrupt rulers have got so good at hiding their wealth that, essentially, once it’s stolen, it’s gone forever, and they get to keep their luxury properties in west London, their superyachts in the Caribbean, and their villas in the South of France, even if they lose their jobs.” Estimates for the total amount stolen each year from the developing world range from $20 billion to an astronomical $1 trillion.

The struggle facing Tunisian investigators is no more apparent than in Switzerland

The struggle facing Tunisian investigators is no more apparent than in Switzerland, which, despite recent reforms and efforts to bolster asset recovery initiatives, has been and likely always will be a haven for dirty money as long as it remains a global financial center. Switzerland is where the largest known amount of the Ben Ali-Trabelsi money is frozen — 60 million Swiss francs ($66 million) — and the Swiss were fast to freeze these assets in 2011. However, a recent column in Swiss newspaper Le Temps, penned by Anouar Gharbi, the deputy secretary-general of the Geneva Council for International Affairs and Development, signaled that the amount of assets in Switzerland could be much more. Gharbi highlighted that a 2009 report of the Swiss National Bank acknowledged the existence of Tunisian assets valuing 625 million Swiss francs ($683 million) — this figure was also mentioned by the then Swiss Foreign Minister Micheline Calmy-Rey during a press conference in 2011. Gharbi writes that Tunisia also previously claimed 114.5 million Swiss francs ($125.2 million) plus interest from HSBC for having harbored Belhassen Trabelsi’s fortune. This claim was nullified after HSBC paid a fine to Swiss banks in 2015 for money laundering.

Swiss legal requirements are especially rigid: To retrieve the money, Tunisia must put the accused on trial and provide clear evidence linking the assets in question to illicit financial activities. In January, France blocked an extradition request for Belhassen Trabelsi (said to be the owner of $40 million of the $66 million) due to the “risk of inhuman and degrading treatment” in Tunis. In 2014, Switzerland was on the cusp of returning Trabelsi’s $40 million to Tunisia, but this was blocked after a last-minute decision by the Swiss Federal Supreme Court, which ruled that federal prosecutors had not paid due diligence to the accused’s arguments.

Swiss journalist Balz Bruppacher, who has closely followed efforts by Arab Spring countries to recover assets in Switzerland, says that after this 2014 verdict, Tunisia lost the possibility to get a quick result and that since then the likelihood of recovering the money from Switzerland has waned: “I don’t think they will succeed in getting back this money as there has not been enough proof provided by Tunisia of the underlying crime.”

Much to the Tunisian public’s dismay, the administrative 10-year freeze on the 60 million Swiss francs was lifted at the beginning of 2021. The Swiss government has insisted, however, that the “majority of assets” will remain frozen and a penal investigation of 11 individuals is ongoing.

Sihem Bensedrine, who led the Truth and Dignity Commission, says that Switzerland needs to be more flexible: “There is enough evidence proving that the origin is illicit, but meanwhile our European partners insist on having this intangible proof. It’s difficult to get this proof because these people are wealthy and they are very well advised; they have excellent lawyers who know how to create the illusion of legality.”

Both Garoui and Bensedrine say that the international community should take the wider political context into consideration. “The whole country is in the course of its democratic transition and is facing an unprecedented economic crisis,” says Bensedrine.

The other major stumbling block in Tunisia’s asset recovery strategy has been its internal failings — notably, its chaotic and slow bureaucracy. When the national committee ended its mandate, the weekly meetings came to an end, and the information that had been centralized was scattered between various ministries and government bodies. Abbes is quick to admit that a lack of coordination between ministries and Tunisia’s sluggish, old-fashioned bureaucracy is a key reason behind the lack of recent success. During the interview, New Lines witnessed this inaction when Abbes said that he was unauthorized to answer certain questions about the current strategy — specifically the amount of money Tunisia has managed to claw back — and that such questions should be directed through the Finance Ministry to the new Committee for the Management of Confiscated Assets (promised interviews with the committee never materialized).

Political turmoil has also redirected much of Tunisia’s attention. Since the revolution, Tunisia has seen nine different governments, each with their own differing priorities. A lack of continuity in government has diminished political will — worsened by a controversial reconciliation law passed by late former President Beji Caid Essebesi that gave amnesty to civil servants who abetted corruption in the former regime. The bill was a step back for both the strategy and the revolution. Currently, President Kais Saied and Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi are in a tense standoff after Saied refused to swear in four proposed ministers in a new cabinet whom he says have conflicts of interest, a move that has paralyzed parliament. Political showmanship between the two men has underlaid everything, from the youth protests that swept Tunisia earlier this year to Tunisia’s COVID-19 vaccine efforts.

Now the asset recovery strategy is the latest victim of their dispute. In November 2020, Saied — who ran on an anti-corruption platform and pledged to make asset recovery a personal project — decreed that a new committee be created to retrieve the stolen assets, saying that the issue had been badly handled. After the leaders’ dispute, however, rifts formed between the presidency and various ministries, and the process has stalled once again.

A decade on from its revolution, Tunisia’s transitional justice process is ongoing, if not on standby. Ben Ali died in exile in 2019 at the age of 83. Today, there is a sense of failure around the asset question. Long gone are the days when journalists were welcomed with open arms into palaces and car auctions. It was difficult for New Lines to get official statements or interviews, with several officials who formerly worked on the strategy refusing to talk on the subject, saying it was too sensitive. “There is a total lack of transparency,” says Bensedrine. “They have done nothing — they have failed.”

Bullough says that this gloominess is unsurprising. “The focus is always on recovering the money, but it’s unrecoverable. They never, ever win. The focus should shift to preventing future corruption.”

Indeed, the recovery process itself has not been immune to corrupt forces. In 2011, a French documentary crew followed Laasad Hmaid, the official in charge of the management of confiscated assets at the time, around Ben Ali’s palace. As he walked through the gates, Hmaid dramatically turned to the cameras, whispering, “You are about to enter Ali Baba’s cave,” before pointing out the enormous, indoor heated swimming pool and bed frames cast from pure silver. Six years later, Hmaid was arrested for embezzling just over $1 million.

“The assets that the state has not managed to sell had serious problems with corruption. … Many judges were charged with corruption for mismanaging these properties and assets. It was a big scandal at the time,” says Garoui. With his 2020 decree, Saied inferred that Ben Ali’s money had not been found because the people in charge were implicated in the corruption, while Abbes said that the clan still has allies in Tunisia and that certain people have created obstacles.

Hammami, the researcher, says that the family were presented as scapegoats: “This stigmatization of the family drew focus away from their surrounding networks who were also complicit in their corruption, many of whom continue to live in Tunisia.

“The confiscation of the assets gave the impression that something changed and now we are moving on. In reality, no: It was just a purge of a small group of people who were presented as a scapegoat of all that happened under Ben Ali,” Hammami says.

Despite the doom and gloom, however, Abbes says that the 10th anniversary of the Arab Spring renewed the government’s attention to the issue, and the public outcry after the lifting of the administrative freeze in Switzerland has put pressure on officials. Abbes says that the government is in the process of relaunching investigations and designating a new legal team.

“Now there is much more political will,” he says, “Everyone is now much more motivated to see this money returned to the Tunisian people.”