Since Russia began its unprovoked war on Ukraine on Feb. 24, images of Ukrainian farmers pulling destroyed or abandoned Russian military hardware with their tractors have captivated followers on social media. The resilience and tenacity of Ukrainians in their David and Goliath fight against Russia has endeared governments and civilians alike in an unprecedented and coordinated display of support for Ukraine.

These and similar images are one type of open-source intelligence, or OSINT, that are increasingly used by intelligence analysts, investigators and journalists to track and trace what is happening on the ground in real time. OSINT includes any publicly available source, much of which can be found online on social media platforms and in videos, webinars and speeches as well as tools such as satellite imagery that can be used in combination to triangulate data and verify facts.

Since the war began in Syria, the field of OSINT has evolved from being a niche interest of online amateur sleuths on the fringes to a mainstream method of investigation and research. Thanks to OSINT, the scale of Russia’s troop build-up on Ukraine’s borders and details about the type of military hardware it was using was known months before the invasion. Since then, data has been collected for a range of categories including materiel losses, targets, casualties and potential war crimes as well as the quality and quantity of equipment and supplies on both sides.

The abundance of images online illustrating the ability of a lesser-equipped but dogged Ukrainian army hanging on despite its superior adversary has surprised many. This has fueled debate among experts, such as military analysts, and data journalists about the veracity of OSINT. Michael Kofman, research program director in the Russia studies program at the Virginia-based CNA think tank, takes a longer view and suggests it’s too early to suggest Russia cannot win its war; after all, Russia has a bigger military and more weaponry. The Ukrainian government, particularly President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, has proved adept at harnessing social media and uniting the population against a common enemy. The abundance of images attesting to Ukrainians’ability to thwart Russian advances may distort the current state of war in Ukraine and inadvertently portray the Ukrainian situation as being better than it is. Yet those who rely on OSINT take a cautious view about drawing conclusions. For data journalists, grand predictions are not the point. Rather, it is to stick to what the data shows.

Information about materiel losses is one point of contention. As of March 28, OSINT suggests that the Russian military has been losing equipment at almost four times the rate as the Ukrainian military, despite Russia’s significant firepower advantage. Only some of this can be explained by early war losses due to the disorganization, supply issues, and Russia’s initial attempts to advance very quickly with the expectation of not facing serious opposition.

There has also been a disparity between documented materiel losses and official claims from each side. The Ukrainian government reports that twice as many Russian losses as can be verified through OSINT, whereas Russian officials report five to 15 times as many losses on the Ukrainian side as can be documented. Some inflation about losses compared with what is documented via OSINT is inevitable because of a mix of overly optimistic reporting by troops and either a lag on or lack of OSINT data. In an environment where access to smartphones and internet is common, a 2:1 ratio of reported losses to those confirmed via OSINT is reasonable. On the Russian side, this difference can be attributed, at least in part, to Russian officials’ outright falsification of information. One example is their claim that Ukraine has lost 33 Bayraktar TB2 drones. This significantly exceeds the number of Bayraktar drones that have been delivered to Ukraine, and there is visual evidence for the loss of just one of these drones.

Since the start of the war both sides have been using reconnaissance drones, so Russia should have relatively easy access to document a large percentage of alleged Ukrainian materiel losses. However, the Russian side has instead relied on a mix of Russian and pro-Russian media teams to post photographs of the same destroyed or captured vehicles from different angles, multiple times.

Different combat strategies between the Russian and Ukrainian armies also explain why the Ukrainians’ materiel losses have been much less than the Russians’. The Russian army uses tanks and other armored vehicles as primary combat assets, whereas Ukraine appears to have been using tanks and other armored vehicles largely as support assets and have been avoiding direct tank-on-tank combat in which Russian troops have an advantage because their tanks and ammunition are more modern. Ukraine has relied to a greater degree on anti-tank guided missiles (ATGMs) and short-range rocket launchers as well as artillery aided by real-time reconnaissance information from various drones. Shipments of such weapons from the West may have influenced Ukraine’s tactical choices, but even before the West supplied such weaponry, Ukraine had a substantial arsenal of both legacy Soviet ATGMs and had recently developed domestically manufactured models.

OSINT provides little insight into the number of casualties because of official secrecy and operational security. But it is possible to make inferences about the effects on casualties and troop performance based on the equipment found, or lack thereof, by using OSINT. For example, minimal medical equipment (which is of poor quality) and medical personnel as well as limited Medevac capabilities point to the likelihood of a statistically significant shift from the usual 1:3 ratio of killed to wounded troops.

Additionally, the small quantity (and mostly low quality) of night and thermal vision devices in Russian troops’ possession indicates their ability to operate at night is limited at best. And while the Ukrainian army has nowhere near the amount it would like of such equipment, it has received significant shipments of this equipment from Western sources before and during the war, giving a noticeable advantage to conduct night raids, inflicting losses and tying down Russian troops.

Based on social media footage, defects observed on some of the abandoned and captured Russian equipment indicate structural problems with the quality of parts and maintenance. It is likely these worsened in the months before the invasion, when large quantities of Russian equipment were placed in temporary and/or improvised forward positions in which only basic maintenance would have been possible. And given the time needed to remedy more complicated vehicle maintenance, this will continue to hinder the Russian military for the remainder of the war.

Relatedly, after the start of the war, Russian logistical problems became increasingly apparent from footage posted by Ukrainian civilians as well as from footage of captured Russian supplies and their abandoned military vehicles. The theft and sale of fuel by Russian soldiers in Belarus (and likely elsewhere) who weren’t aware that they were about to participate in the war was widely known. The Ukrainian military had valuable information, all openly sourced, about the significant vulnerability of enemy forces, which they may have used to their strategic advantage.

The size of Russian convoys entering and/or holding various positions in the initial days of the war could be determined from footage captured by publicly accessible roadside cameras. As the war has progressed and with internet access preserved, at least for now, videos from areas occupied by Russian troops have provided a constant stream of data about the movement of troops and equipment as well as protests by the local population. Far less information of this kind has been available from the Ukrainian side, which may have given them a tactical advantage in how they targeted the Russian military.

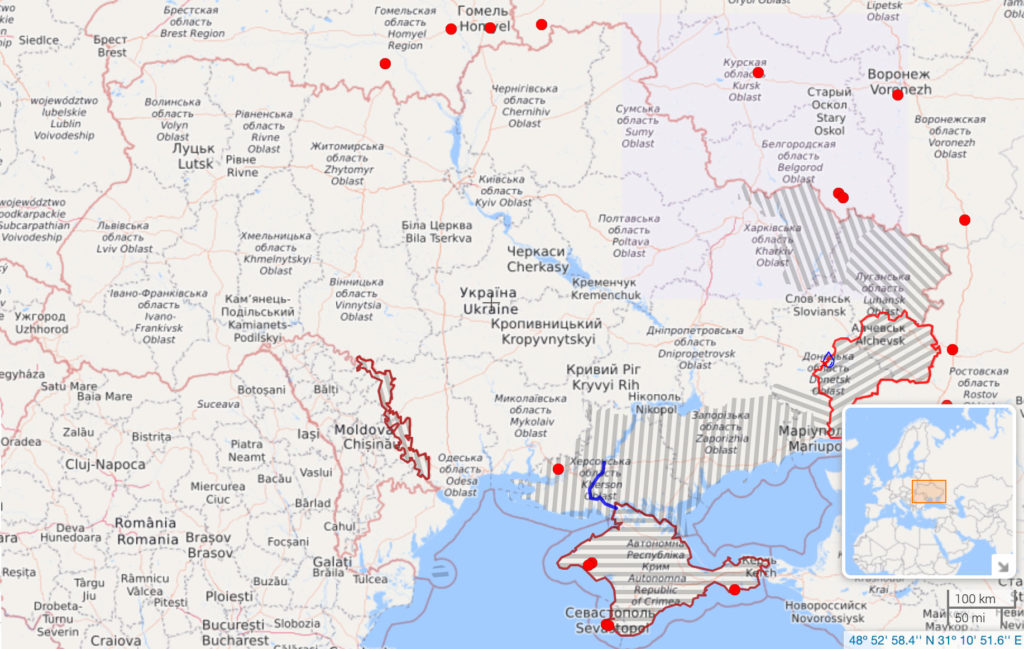

Russia’s inability to take full control over captured areas (beyond some traffic routes and government facilities) gave Ukrainian units time to reorganize and start attacking Russian rear units, making it difficult to determine the level of territorial control the Russian military has in most places. It has been easier to track the situation in southern and southeastern parts of Ukraine, where front lines are better established; the situation is different in northern and western parts of the country. This is shown on the Liveuamap image from March 28.

In the Russia-Ukraine war, as with the Syrian conflict, OSINT is an effective tool for assessing trends and narrowing down likely short-term outcomes. There are limitations with OSINT: It can’t be used to predict the outcome of conflicts. It would also be inappropriate to draw conclusions about the war’s outcome based solely on the pictures of civilians towing Russian military vehicles. But using OSINT to narrow down the level of uncertainty in the gains and losses on both sides can be useful for shaping expectations.