Listen to this story

The most famous poem in all of Arabic literature, penned by the pagan prince Imru’ al-Qays around one century before Islam, happens to contain what must be one of humanity’s oldest surviving wine reviews.

This epic, 81-line autobiographical ode, which legend holds was affixed to Mecca’s Kaaba along with several other poets’ magna opera in honor of their literary genius, is a vivid recollection of its author’s escapades through the Arabian desert, with passages ranging from boasts about sexual conquests to an extended paean to his horse. It’s in the closing lines, as he depicts the aftermath of a violent rainstorm that the poet likens a noisy flock of birds to a group of rowdy drinkers:

It was as if the larks of the valley, at dawn

Had supped a fine, peppery vin de goutte

The Quran tells us the wine in paradise, by contrast, has the heady aroma not of pepper but of the perfumes musk and camphor.

The Prophet Muhammad’s preferred poet, Hassan ibn Thabit, compared one wine of Capitolias (in modern-day Jordan) to “succulent apple, freshly picked” in a famous ode defending God’s Messenger.

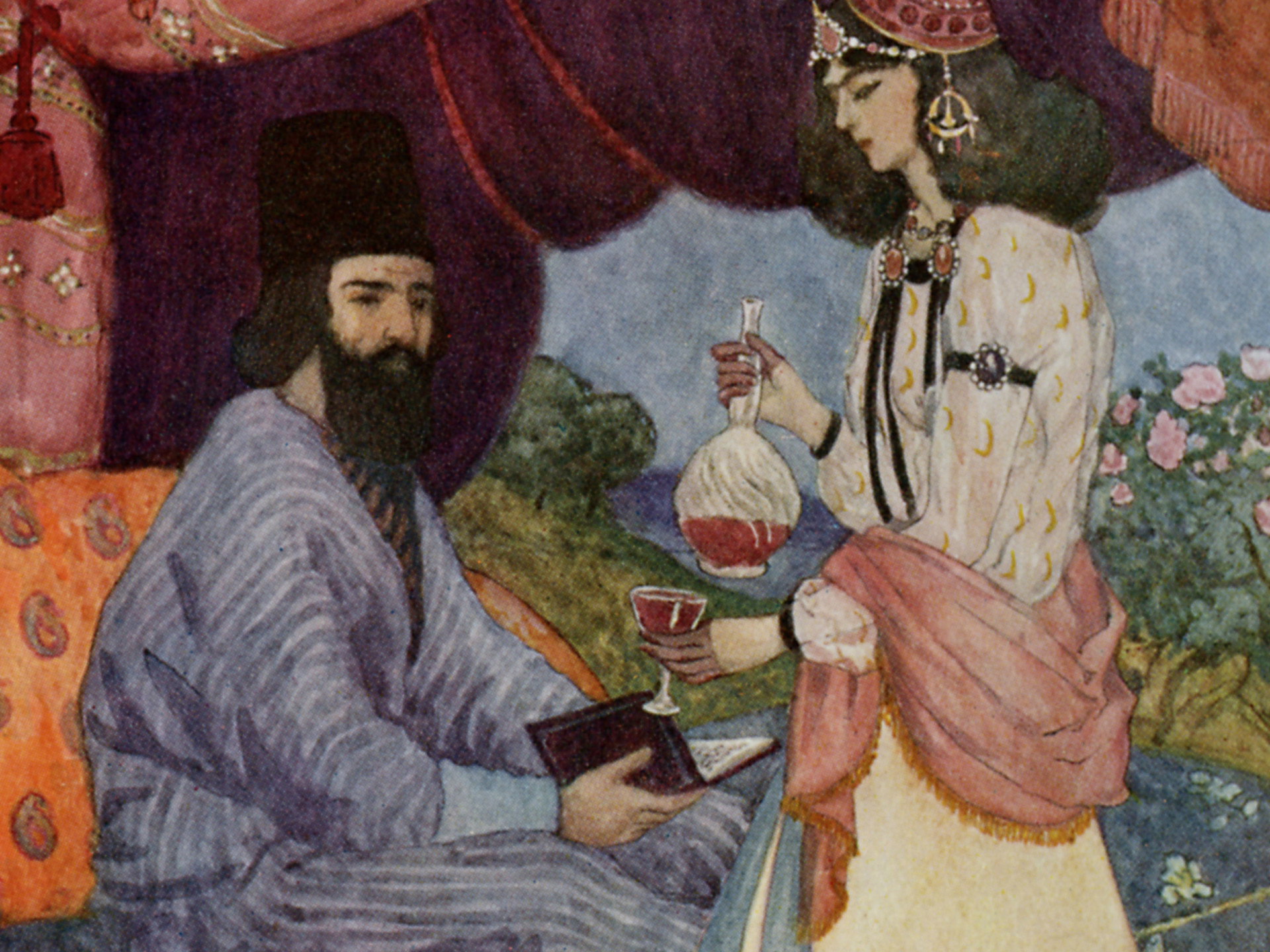

A century later, in Damascus, the sovereign of the Muslim world, the Umayyad Caliph al-Walid ibn Yazid — who was said to enjoy a glass or two — dutifully echoed the Lord in citing notes of musk in the vintages he extolled in his own scandalously impious verse.

As for the undisputed master of classical Arabic wine poetry, Abu Nuwas (an Arab court poet of the libertine Abbasid Caliph al-Amin in Baghdad, and a character in the Create a free account to continue reading Already a New Lines member? Log in here Create an account to access exclusive content.