Listen to this story

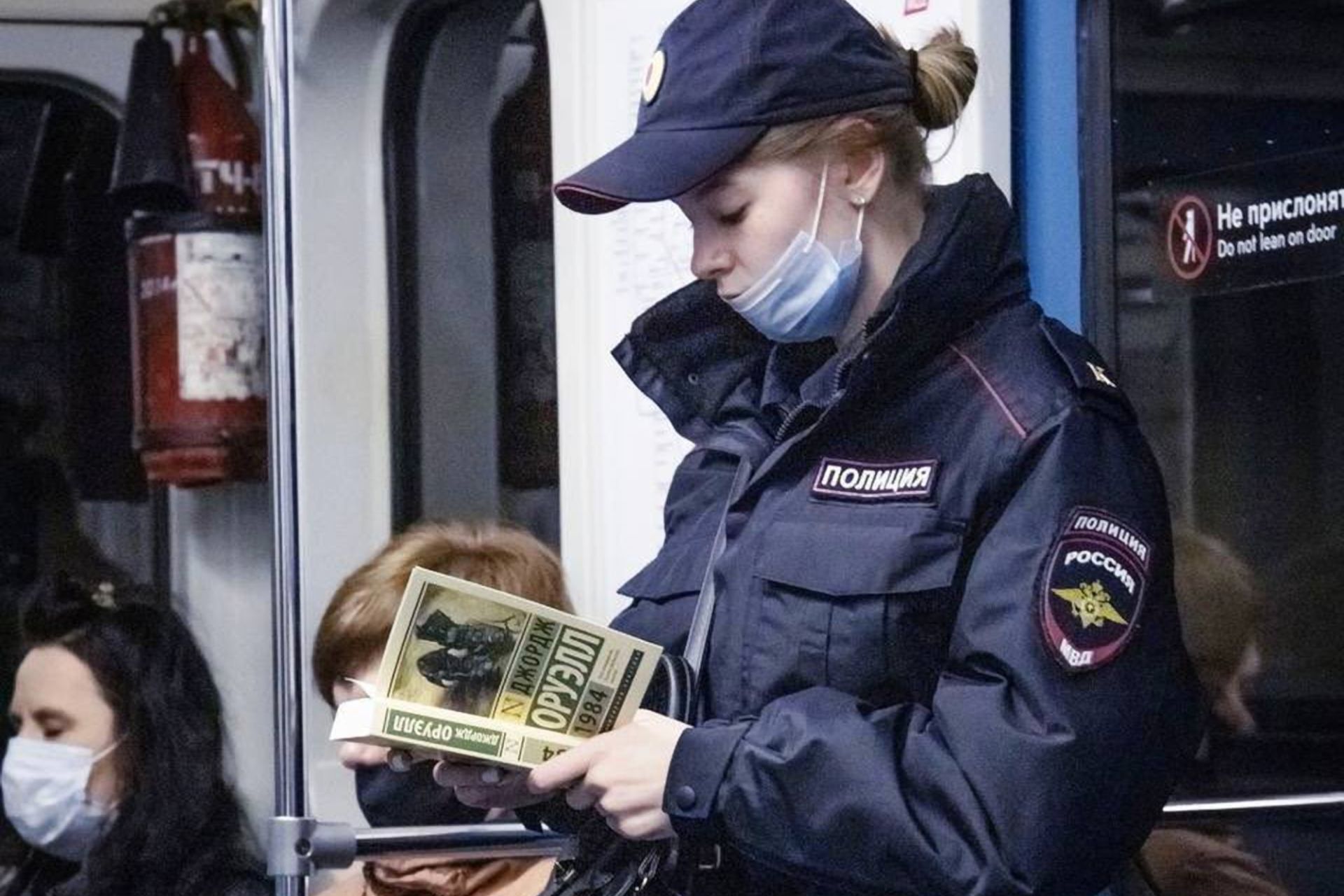

The most poignant line in George Orwell’s “1984” belongs to a minor character, a grief-stricken old man whom the novel’s hero, Winston Smith, remembers seeing long ago in an air raid shelter. Having lost (Winston imagines) a beloved granddaughter, the man kept repeating to his wife,

We didn’t ought to ’ave trusted ’em. I said so, Ma, didn’t I? That’s what come of trusting ’em. I said so all along. We didn’t ought to ’ave trusted the buggers.

Although it’s not immediately clear to Winston just who shouldn’t have been trusted, it seems the man is talking about the warlike political party that, by the time of the novel’s main action, controls Winston’s entire reality.

In the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the line called to mind Sergey Bokov, a 23-year-old Russian soldier quoted by the BBC. Bokov, who had been sent to the Ukrainian border on a supposed exercise, said he didn’t realize his government had flung him into a war until he noticed road signs in Ukrainian and Ukraine’s resistance began. “They deceived us beautifully,” he told the BBC. Create a free account to continue reading Already a New Lines member? Log in here Create an account to access exclusive content.