When the war began, 51-year-old Kostiantyn Bidnyi was living with his family in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv, where he worked as a senior manager at a printing plant. Bidnyi, who goes by Kos, is an avid militaria collector of mostly WWII helmets and is active in the online community of fellow collectors on Facebook. After Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February of last year, he wanted to help his compatriots in their cause. He reached out to friends he had made online and began trading mostly German WWII helmets from his collection for modern Kevlar helmets that he could then donate to the Ukrainian army.

Soon, people began to reach out with, as he put it, “requests to help them buy a Russian combat helmet, like a trophy from the battlefield.” Bidnyi quickly became a prominent middleman in the burgeoning market of selling items picked up from battlefields by Ukrainian soldiers, shipping them westwards and funneling the money back to the original soldier or unit who found them. Soon, Instagram accounts and Facebook pages filled with Russian equipment, uniforms and patches, despoiled from dead and captured Russians — all with price tags. The strange world of collectibles and military souvenirs found its way from the blood-drenched battlefields of Ukraine to the social media age.

“Naturally, having friends who participate in battles serving in the Ukrainian army as volunteers or military personnel, it was not difficult for me to organize such a process: to help collectors have a historically important trophy, and my friends in the army receive material support,” Bidnyi explained in an interview over Facebook.

The modern battlefield can become cluttered with an incalculable amount of waste. For many Ukrainian soldiers, the detritus of war — from shell casings, bandages, helmets, uniforms and equipment taken off the dead and wounded — are trash to be bulldozed and burned. But for militaria collectors abroad, there is gold in these piles. Ukrainians have been able to develop a market for many of these items, turning the garbage of war into a much-needed fundraising pipeline.

Many of those who support Ukraine from abroad have looked for material ways to back the war effort. Fundraising initiatives like Saint Javelin, an organization raising money by selling merchandise with a saint holding a Javelin anti-tank missile in the style of a religious icon, have been incredibly successful, sending some $2 million worth of support to Ukraine. On a smaller scale, a network of militaria collectors from around the world has been able to support Ukrainian soldiers and units directly by buying Russian items collected off the battlefield. Organized on social media and connected by Ukraine’s postal service, these collectors trade in Russian patches, battle-damaged equipment and uniforms.

“The main thing is that my friends at the front receive support, and the community of collectors has the opportunity to feel their involvement in the fight against evil,” Bidnyi says.

Three months after the beginning of the invasion, Bidnyi set up a private Facebook group to help facilitate the sale of more items. With 2,000-plus members, the group has become one of the centers of the market for these items. As Bidnyi says, “I was not unique in this business.” One can find captured uniforms and equipment on most online resale platforms like eBay, and direct sales occur on social media platforms such as Instagram and Reddit. But the Facebook group that Bidnyi started is one of the largest groups dedicated to the business (he asked that its name not be disclosed, due to security concerns).

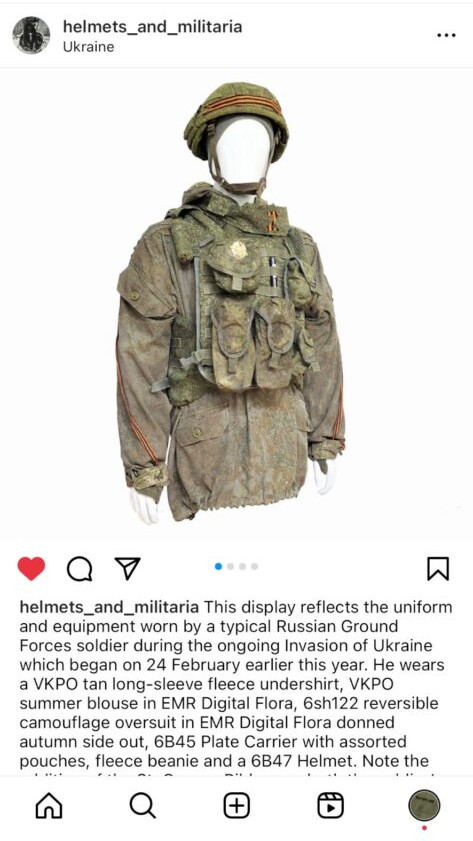

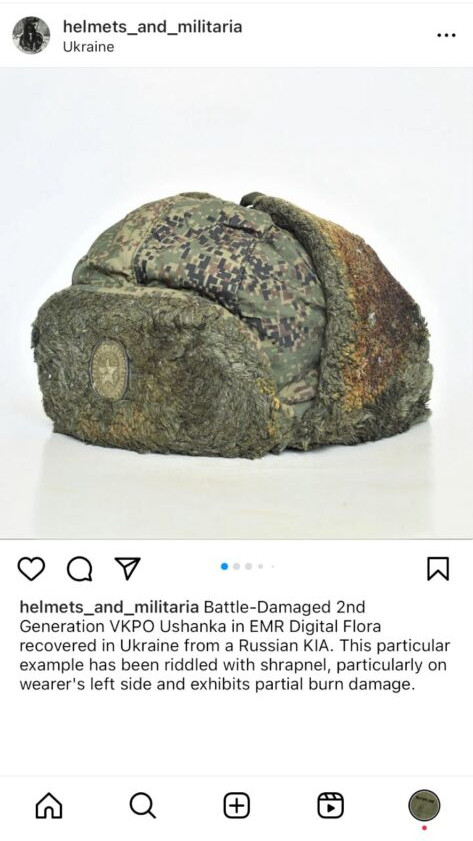

The trade is so demanding that, in May 2022, it became Bidnyi’s full-time job, with funds going to support a variety of units fighting in Ukraine, including the 65th Mechanized Brigade, the 92nd Mechanized Brigade, the Georgian National Legion and the 77th Airmobile Brigade. Bidnyi never fully recorded the money he raised, but he is confident tens of thousands of dollars passed through him “to those military men who provided me with these trophies.” Sold in an auction format, where bids are placed in the comment section, buyers can score a full battle-worn Russian uniform for $80, or a camouflage baseball hat taken from a member of the Wagner Group outside of Bakhmut for $250. All of these items have been collected from the battlefield, taken from prisoners of war, or from the dead. Helmets and items from the Wagner Group, bearing the now-notorious “Z” or orange and black ribbon of Saint George — used to identify Russian soldiers on the battlefield — fetch the most from collectors. Helmets can reach up to $800 and a jacket and gear belonging to a Wagner member recently sold for $470.

With a war that is so well documented by its participants, it should be no surprise that provenance is such a vital part of the collectors’ market. Items auctioned off on the Facebook group often come with images or videos showing them in situ on the battlefield where they were originally found. Recently, a video was shared in the group showing members of the Georgian National Legion, a paramilitary group fighting for Ukraine, ambushing a group of Russian soldiers reportedly of the Wagner Group. The video, shot in December 2022, ends by showing the bodies of eleven Russian soldiers. Pieces of kit taken from the dead Russians in the video were posted in the group for auction.

“If you’re looking for military relics with direct provenance, this is for you, narrowed down to battle, date, and location. Collected directly from specifically to offer here, the smell of cordite and the field are strong on these items,” wrote Shannon Paul Reck, an admin on the Facebook page, a collector himself, and the official point of contact for fundraising operations of the Georgian National Legion in the US and Canada. The auction post went on: “these are not random pick ups and people died wearing these things and all are from this video. I don’t believe in ghosts really but there is a somber energy. You’ll see if you win an item.”

Trading in war “relics” from past conflicts like the Napoleonic Wars or WWII is a relatively normal, if eccentric, pastime of collectors. But helmets, bags, clothing and shrapnel-pocked pieces of vehicles being taken off battlefields and brought into the marketplace in near-real time is a new occurrence — facilitated by e-commerce, social media and Ukraine’s relatively stable connection to the global supply chain.

While the means of acquisition may be modern, battlefield souvenirs or trophies are far from new. Throughout Homer’s “Iliad,” warriors are shown stripping the vanquished of weapons and armor.

“Spears, if you want, both one and twenty you will find / standing in my hut near the shiny walls, / Trojan spears, which I take away from the dead,” says Idomeneus to Meriones. More famously, Hector strips Patroclus of his armor after slaying him. In the modern era, soldiers returned from WWII with looted helmets and flags, while U.S. troops in Vietnam traded in captured belt buckles and insignia.

“Taking trophies is probably the longest tradition in warfare,” says Russ Ames, a militaria collector based in Florida. “But nowadays, with the internet and everything, it’s very easy to get stuff. … People who are fighting can get [trophies] about as easily as someone who is on the other side of the world.”

Legally speaking, the current trade in what international humanitarian law calls “war booty” is a bit murky. While the Hague Convention of 1907 says that “private property cannot be confiscated,” military equipment and other items belonging to an enemy force in combat can indeed be captured and then used by the victorious force. According to “The Domestic Implementation of International Humanitarian Law in Ukraine,” since 2021, “The parties to the conflict may seize military equipment belonging to an adverse party as war booty.” But, according to an earlier version of the manual, “booty of war belongs to the State and not to individual servicemen.” Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense did not reply to a request for comment from New Lines about the trade in captured pieces. While there may be something disquieting about the practice happening in real time, it is a timeless part of war, one of the many small horrors that has accompanied warfare since time immemorial.

The cyber markets selling Russian uniforms and equipment offer various clues as to Moscow’s performance and abilities on the battlefield. This is a military that still draws on Soviet-era equipment. Observers of the conflict have noted this since the early months of the war, with the Russian military using ever-older stocks of vehicles and tanks. The same is true of the soldiers fighting. Since the start of the conflict, Soviet-era belt buckles have been common along with Cold War-era steel helmets usually used by soldiers from the breakaway Luhansk and Donetsk “people’s republics” in the east of Ukraine. What isn’t being recovered from the battlefield can be equally telling. Reck has noticed more uniforms being collected without any type of insignia, supporting a prevalent narrative that Russia is sending its newly mobilized soldiers straight into the fight with little training or equipment. “They’re short of insignias. They’ll just give them a uniform, maybe a helmet,” Reck says.

The flow of battlefield pickups directly correlates to the state of the war. When the Ukrainian military is on the offensive and pushing forward, the flow of items picks up.

“The September Kharkiv counteroffensive, there’s loads of stuff, way more than usual because of how quick people were moving and towns were getting captured,” explained Ames. So far, the flow of items seems to have remained steady as the anticipated summer counteroffensive began. At the same time, there has been a noted correlation with Ukrainian postal officials cracking down on items leaving the country when the news is less favorable from the front. “They told us that all military items, and dual purpose items, are prohibited from mailing without special permission from the export control committee,” explains Bidnyi of his meeting with Ukrainian customs officials about the matter.

Reck knew he wanted to help the Ukrainian cause. He started by simply donating whatever money he could regularly. Soon he got in touch with the Georgian National Legion, selling their unit shoulder-sleeve patches as tokens of support in the U.S. to help raise money for the unit. First, he began as a buyer on the Facebook group.

“I wanted to help, so I jumped on their page mainly as a consumer,” he says. But his goal was always to bring the Georgian National Legion into the group, seeing it as a way to boost their fundraising by selling Russian uniforms and equipment they took from the battlefield. They send him boxes of items from Ukraine, which he then posts on the Facebook group for sale. The buyers pay the Georgian National Legion directly and Reck ships the items.

“Each round of ammo or bandage I can provide helps Ukraine contain Putinism to prevent us, you, our friends, and our families from being forced over there to fight something bigger later,” says Reck of the funds he is able to raise by the sales. For the individual soldier, selling items scavenged from the battlefield could help them upgrade their personal equipment like their body armor or helmet, according to Ames. “A soldier goes to Bakhmut with the equipment that he and his family, his friends can help crowdfund for,” commented Joe Barnes on the British newspaper The Telegraph’s podcast “Ukraine: The Latest.”

For collectors, the pieces they buy from Ukraine run the gamut from mundane to macabre. Ames, who buys and sells militaria from numerous time periods and is working on a book on Saddam-era Iraqi helmets, has collected over a dozen pieces from the war, including a full Russian field uniform that included muddy boots and a toiletry kit with toothpaste and toothbrush. “Some guy could have been captured, his uniform taken off, and then a month later it’s in the United States in a collection,” Ames says.

Khang Nguyen is another young collector in the U.S. From a family of Vietnamese immigrants, he would go on walks with his grandfather, who told him stories from his life in Vietnam, which spurred his interest in history and conflict. At first, he started collecting militaria from the Vietnam War but soon felt priced out of that market. Connecting with other collectors on social media, he acquired pieces from Ukrainian soldiers before the 2022 invasion. With those contacts, he began to collect Russian helmets and uniforms after the invasion began. Like other collectors, he shares much of his collection on Instagram, which includes shattered Russian rifle magazines, burned Russian Ushanka hats and multiple helmets in various conditions. After starting the Facebook group in May 2022, Bidnyi recently joined the Ukrainian army himself, leaving Reck to take on the main administrative role of the group. Fellow administrators include Ukrainians as well as others from a variety of countries, including Australia and France. “Any support in the rear is very important to my friends; this motivates them even more since they have been living in inhuman conditions for more than a year, risking literally everything,” Bidnyi says.

As Reck puts it, the sale of these battlefield pickups helps provide logistical support that would otherwise not be available. “For me, collecting and distributing these items isn’t about self-investment, but supporting the future of a country unjustly invaded.”

It is hard not to think of Hector removing the armor from Patroclus’ body in the “Iliad” when you see a Russian plate carrier for sale — the armor must be removed from its owner in much the same way, almost three millennia later. There is a seemingly innate human desire to collect objects that bore witness to conflict — to memorialize it, to prove it happened, to make it all seem worth it. While the way souvenirs and war trophies are being sold is thoroughly modern and unique to this war, the desire for the objects is as old as war itself.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.