Listen to this story

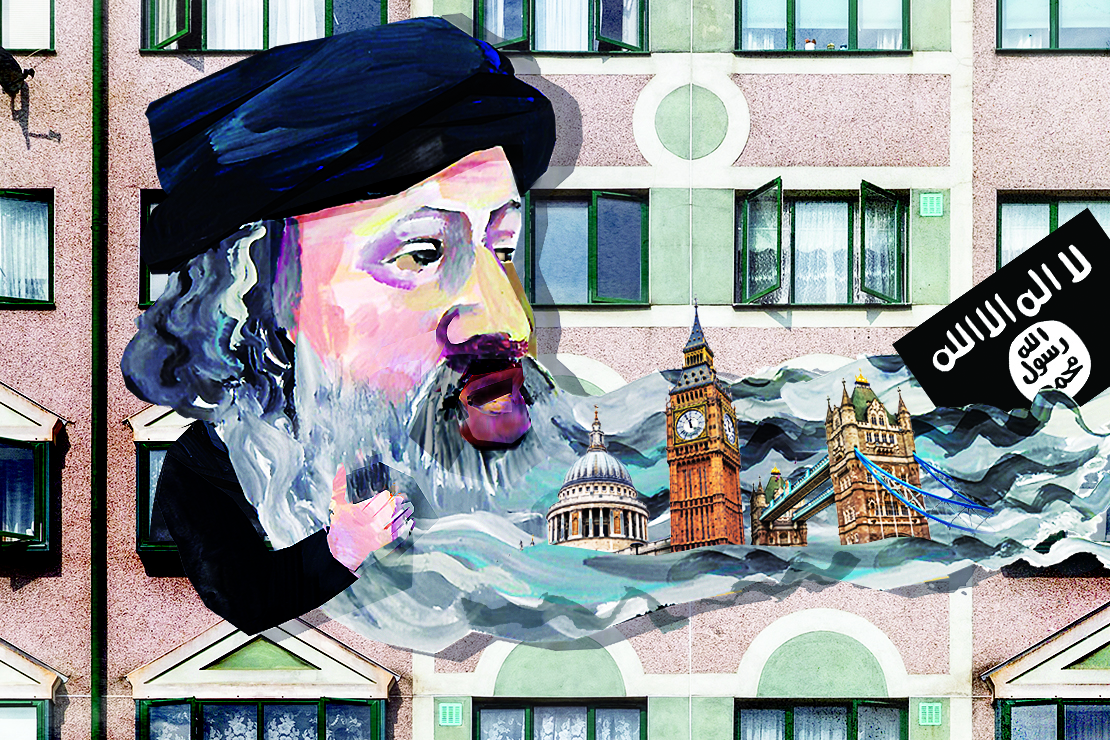

Opportunities to meet a caliph are pretty rare. Yet in London in the 1990s, you could bump into a protector of the entire Muslim world on the Central line. He wore no finery, of course, and his palace was a two-bedroom government apartment in Dagenham. How did a seemingly unremarkable figure leave such an extraordinary footprint in jihadist discourse?

Muhammad al-Rifai didn’t initially want to be caliph, but he held sway over 5,000 followers from all walks of life, in locales stretching from Nelson, Slough, and Maidenhead to Pakistan, Bangladesh, Chad, Sudan, the Philippines, and Afghanistan, even before the days of Twitter. His group, though small, foreshadowed much of what would come to pass a decade later. Some of his men went on to play a significant role in Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s caliphate.

Muhammed al-Rifai, also known as Abu Hammam al-Filistini, was born in 1959, the son of an illustrious family immersed in Islamic mysticism. The Rifais were closely linked to the Sufi order of the same name and were of prophetic lineage. Although the family name cropped up all over the Near East, his own branch was Palestinian. Following the Nakba in 1948, his family found refuge in Zarqa, half an hour’s drive from Jordan’s capital Amman.

Zarqa is an obscure, dusty town whose most famous export so far has been Salafi jihadists like the founder of al Qaeda in Iraq, Musab al-Zarqawi. Like many of his compatriots, Rifai knew the taste of dislocation and became an orphan in search of a cause. While some Palestinians with secular temperament joined leftist organizations in the 1960s and 1970s, those with a religious inclination like Rifai joined Islamist movements.

When the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, Rifai had already left his studies in Medina for a physiotherapy course in Punjab University, Pakistan. In Lahore, Rifai responded to fellow countryman Abdullah Azzam, who urged young Arabs to help the Afghans fight the Soviet forces. Rifai’s followers claim that he fought alongside Azzam at the tail end of the Soviet invasion, but they are short on details.

Abdullah Anas, one of the founders of the Arab Services Bureau – a clearinghouse based in Peshawar for Arab mujahideen – bumped into him in 1983 as he was working for the Red Crescent. Rifai, he recalls, was “polite, friendly and devout.” He met him again in 1992 and found him more hardline. It’s difficult to ascertain why. Was it the effects of war or the influx of radicals coming to Peshawar in the late ‘80s? In any case, one of Rifai’s closest acolytes told me that Rifai presented Azzam with a plan to take over Pakistan before leaving the Islamic Republic for Jordan. Azzam had no ambitions for global jihad against an enemy near or far and rejected the proposal. But what was noteworthy was that Rifai was already toying with the idea of establishing a transnational Islamic polity.

When the Gulf War broke out in 1991, Rifai had left the Muslim Brotherhood and was deeply disenchanted with the Hashemite Kingdom’s general pro-Western stance. By then, he was a follower of the Palestinian Salafist jihadist preacher Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, distributing his works and calling for jihad against the Americans. In response, the authorities flung him into prison for four months. It was during his incarceration that he met a young tough from his adopted hometown: Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

As a student of Abu Qatadah al-Filistini, Jihadism’s foremost scholar, told me, “[Rifai] had an ability to get you to practice in an easy and understandable way; Abu Musab fell under his influence.” While Zarqawi headed to Afghanistan, Rifai traveled to the United Kingdom after a brief stint in Peshawar. Once in London, he purportedly shared a flat with the Tottenham ayatollah Omar Bakri Mohammed, the founder of al-Muhajiroun, a Salafist jihadist network from which many future British ISIS fighters would emerge.

When the Afghan communist regime fell in 1992 – three years after Soviet forces departed – the Afghan mujahideen factions immediately set about fighting for the spoils. In addition to that, the 1989 assassination of the Afghan Arabs’ spiritual leader Abdullah Azzam left an immense void in their midst. In such circumstances, some Afghan Arabs – no doubt influenced by the Pakistani Islamists who also called for the return of an Islamic emirate – began looking for an Aragorn-like savior who would unite them.

The majority of the factions involved in Afghan jihad arguably failed to grasp the political reality or even the complex history of the institution of the caliphate. In theory, the caliph was the ruler of the Muslim faithful and served a politico-religious function. Up to the 13th century, he was a descendant of the Prophet’s tribe of Quraysh. But fighting over who should be the legitimate caliph started right after the Prophet’s passing. After 750 C.E., there were two and later three caliphates. The Abbasids, the Fatimids, and the Umayyads all competed for the loyalty of the faithful. By the 10th century, the caliphate had become a shadow of its former self and a plaything of dynastic sultans who paid nominal lip service to the institution until it was snuffed out in the 1258 destruction of Baghdad by the Mongols, after which it nominally existed under the Mamluk dynasty in Egypt until the early 16th century.

It was the arrival of Ottomans in the Middle East in 1517 that revived the institution, but they claimed the title of caliphate for themselves even though they were not from Qurayshi ancestry. By then, however, the criteria for caliph had changed, and being of Meccan lineage became less important. The Ottomans emphasized their status as a sultanate far more than a caliphate. Briefly around World War I, Ottoman ruler Abdul Hamid II invoked his caliphal title for political purposes, but the empire was crumbling by then. Kemal Ataturk’s abolition of the caliphate a few years later, in 1924, along with the rise of Arab nationalism, gave Arab Qurayshi ancestry a new significance because it bolstered the Arab nationalist cause.

Despite its abolition, the institution did not lose its potency in the Muslim imagination. For some Arabs in Peshawar, arguably an Arab caliph encapsulated the hopes and dreams they could not realize in their own homelands. Other claims for the Commander of the Faithful had not ended well. Jamilur Rahman, an Afghan subordinate of the mujahideen leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, reigned until an Afghan Arab blew out his brains as Rahman was leading him in prayer. Even in Europe, the Caliph of Cologne, Metin Kaplan, a Turkish asylum seeker, was involved in a lengthy battle with the Caliph of Berlin, Halil Ibrahim Sofu, which resulted in Sofu’s killing by unknown assailants.

The search for a caliph then was an emotional argument, not a rational one. For the American-Palestinian Abu Othman, a born-again Muslim who started the search, it didn’t even matter whether the caliph could wield political power or not. As long as the oath of allegiance was offered in the same way the Companions had to the Prophet while he was politically powerless in Mecca, it was enough. God would do the rest.

Abu Othman and his helpers offered the post to several candidates, but none, it seems, were keen on the job description. One of the most noteworthy was the late Abdul Hadi Arwani, the imam of Al-Noor Mosque in Acton. He became heavily involved in the Syrian uprising, even sending some of Britain’s first jihadists like Ali al-Manasfi to Syria. His mosque also became a favorite haunt for the notorious ISIS hostage-takers known as the Beatles. Arwani was later murdered in 2015 by the director of the mosque Khalid Rashid and his accomplice Lee Cooper, a former gang member.

After much deliberation, on April 3, 1993, Rifai – the third-choice candidate – accepted the overlordship of nearly a billion Muslim faithful. Refusal to recognize him would result in excommunication.

The new caliph did not slack in his duties. He set to work preaching to North African devotees in study circles off Golborne Road in West London. He eventually gathered enough followers to take them to Afghanistan to begin his start-up proto-state. It was a disaster.

His critics depicted him as a demented Muslim version of Kurtz from Conrad’s Heart of Darkness – a caliph who allied with unscrupulous warlords, boy-lovers, and drug smugglers. He demanded fealty from Osama bin Laden, who had newly arrived in Jalalabad in 1996. He wrote an ultimatum to the Pakistani Prime Minister, Nawaz Sharif, like the Prophet did to the Sassanid emperor Khosrow II: “embrace Islam and be safe.” In the end, the Taliban leader Mullah Omar, who also claimed to be the Commander of the Faithful, lost patience and hounded him out of the country, ending his project.

Despite the comical and bizarre appearance of his actions, Rifai’s violence should not be dismissed. Anas calls him “a veritable Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi Lite,” and there may be some truth to it: His followers, like the forerunners to ISIS, were accused of killing, kidnapping, raping and enslaving women.

Rifai returned to London in the late ‘90s with his project in tatters. His son Hammam, his daughter, and many of his followers were dead, yet he was curiously optimistic. In the debacle of retreat, he contracted pneumonia; a vision of the Prophet reassured him that he was on to the truth and counseled patience. (Muslims believe that dreams are a small portion of prophecy.) And so he remained undeterred by the setback, moved into a two-bedroom council flat in Dagenham with his wife, and began anew.

But he wasn’t alone; he still had a loyal following. One of his acolytes was a young Kuwaiti, Hussein Lari Reda, also known as Abu Omar al-Kuwaiti, who stayed with him for two years in London reorganizing his movement and remaining loyal to the very end. Even as Rifai tottered on death’s door in 2013, Abu Omar boldly demanded that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi offer his allegiance to the caliph.

The 1990s in London were a tumultuous period for Islamists of all shades, including Rifai. London had become what Cairo and Beirut had been for the Arab world’s awakening in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Both exiled and homegrown Islamists were coming to terms with their political decline. At the peak of Muslim power, the Ottomans had banged at the gates of Vienna; now U.S. troops were outside the gates of Mecca.

Islamists came up with their own political philosophies as different from each other as night and day – from the Tunisian Ennahda party, modeling its approach on British parliamentary democracy, to those who wanted to plant the black flag over 10 Downing Street. Amongst adherents to all these different ideas stood Rifai, demanding fealty.

His followers burnt their passports in front of Regent’s Park Mosque while Islamists mocked him. But it was undeniable that the caliphate loomed large in the Islamists’ own political consciousness. Had the Brotherhood not been a response to the dismantling of the caliphate? Did Hizb ut-Tahrir, a group founded by the Palestinian scholar Taqiudin al-Nabhani that aimed to re-establish the caliphate, not have their own imam-in-waiting? Hizb ut-Tahrir recruited on university campuses with fried chicken, shisha and tea followed by a hard sell of establishing God’s existence using Aristotelian logic, mixed with a cocktail of Islamism and Marxism and voilà! “Brother,” ran the refrain, “if you don’t work to establish the caliphate, you’re sinning.”

These movements might appear astute politically, but they failed to understand something that the likes of Rifai and Baghdadi did: The caliphate was a dream. When the Brotherhood in Egypt was thrown into Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s prisons and Hizb ut-Tahrir was emasculated by al-Baghdadi’s caliphate, ISIS members chose to show themselves burning their passports in a similar fashion to Rifai. Baghdadi understood that feeling; the caliphate was the solution for the alienated and was there to soothe their disaffection.

No one could have foreseen how the ideas bandied around so easily in the ‘90s would metastasize. While the British security services were aware of Israeli-Palestinian tensions flaring up and Islamist attacks abroad, Islamists were not seen as a major threat on home turf, especially from the likes of Rifai.

The lead up to the 9/11 attacks shifted the threat calculation somewhat. Homegrown terror became a real possibility. And the British security services began to flesh out a counter-security strategy they dubbed “CONTEST”. But the perils of the jihadi threat at home only clarified after the 7/7 attacks in 2005. This singular event inaugurated the counter-security architecture in which we find ourselves currently entangled. Arguably, before that the security services didn’t have the imagination nor the proper expertise to assess the likes of Rifai in 2001.

Rifai was a chameleon, at times appearing like a Salafist jihadist, other times intensely critical of bin Laden and suicide bombings, whether in Palestine or New York City. He never advocated the breaking of the law in the United Kingdom but turned a blind eye when his followers robbed, defrauded, and treated the country as if it was at war with the Muslim world. Like al-Muhajiroun, he believed they had to emigrate to a Muslim land to build a community where Islamic law as they understood it was supreme. So he was left alone, free to move his court to a two-bedroom duplex flat in Lisson Green in 2001.

Lisson Green was a place of Islamist ferment. Abu Qatadah preached at Four Feathers Youth Club on Fridays, a stone’s throw from Rifai’s home. The youth club was, as jihadist ideologue Mustafa Setmariam Nasar says, “a place where bulletins were distributed, donations were collected and a place where jihadists and zealots gathered.” His sermons were attended by jihadi luminaries: Zacharia Moussaoui, a 9/11 plotter; Abu Doha, a manager of an al-Qaida camp; Seifullah ben Hassine and Tarek Maroufi, the founders of the Tunisian Combatant group; and many others.

It was hardly surprising that the area produced men who made global headlines. Bilal Berjawi went on to become an al-Shabab commander. Mohammed Emwazi, Alexanda “Big Sid” Kotey, Hudhayfah “Red Beard” Gerbouzi became ISIS hostage takers and executioners known as the Beatles (the latter two have just been extradited to the U.S. where they face a raft of charges for the murder of American journalist James Foley). These young men were able to articulate Jihadism to a new generation of disaffected Muslims in the West. They shaped the image of ISIS in the public imagination and acted as a bridge between older generation of Jihadism and the new. Kotey recruited Tarik Hassane, the son of a Saudi ambassador, to plan mass murder on the streets of London.

But Rifai wasn’t interested in plots to attack the far enemy. He was preoccupied with state building. By 2006, he had followers spanning from Chad to Maidenhead and settled on Bangladesh as the new home for his caliphate. Under the very noses of the Bangladeshi authorities, he had persuaded some dirt-poor islanders to swear allegiance to him. In his mind, he had calculated that the Bangladeshi government wouldn’t even notice the setting up of a nascent proto-state on a flood-prone little island in the world’s most fertile river delta. This time, he treaded carefully; he had learned from his mistakes. He married a local woman, accepted fealty from a Bengali religious scholar, and had financial backing from several wealthy factory owners in the country. Whether it really was a proto-state or merely a figment of his and his followers’ imagination remained open to question.

In London, among the crusty chicken shops off Church Street Market where hawkers sold their wares, Rifai’s helpers fought his critics. Sometimes they tussled with the fiery Jamaican Sheikh Feisal known for his liberality in excommunication. But the intellectual jousting was handled by three men: Abu Ayoub Al-Barqawi, a Moroccan of Tuareg descent who was the group’s hadith scholar and frequent visitor to the United Kingdom; Abul Fadil al-Sudani, who acted as the group’s legal judge offering guidance to the caliph’s followers; and finally Abu Omar al-Kuwaiti, armed with a postgraduate degree in Islamic Studies in Kuwait and boundless energy. The latter authored many of the group’s texts used to indoctrinate its followers. In 2005, he even aimed to set up an evangelical TV channel in the United Kingdom on the lines of Peace TV to propagate his master’s ideas, but it failed due to a lack of funds.

It helped, of course, that most of Rifai’s opponents were runts in terms of religious learning. Feisal had spent eight years studying in Saudi Arabia’s Medina University but could barely string an Arabic sentence together. The main danger came from Abu Qatadah. Although he didn’t have field experience, he was learned; the Palestinian had become, as Nasar says, “a jihadi reference point.” And when Abu Qatadah said that Rifai was a crank, it carried immense weight. The proposition that one man could claim authority on behalf of the whole Muslim nation appeared to be an absurd one. To make such an immense claim, one needed the support of the majority of Muslims or those who could act on behalf of them, at least. But Rifai’s scholars replied with a simple argument: The Prophet did it, so why not his descendant in London? And it was, of course, the same argument that al-Baghdadi used when he declared himself caliph in 2015.

But Abu Qatadah’s undoing came from his own position as editor of al-Ansar magazine, the mouthpiece for the Algerian Civil War. When he defended the Armed Islamic Group of Algeria (GIA) targeting innocent civilians, Barqawi seized on the words and penned a strongly worded denunciation imaginatively titled The Fatwa Against the Criminal Mufti who Justified the Killing of Civilians. Even though Abu Qatadah eventually renounced the GIA, the damage to his reputation was done, and the caliph survived his broadsides.

The 7/7 attack was a clarion call for the British state. The blasé attitude towards Islamists agitating on home soil was abandoned. The authorities seized Omar Bakri, Abu Qatadah, and Rifai. The caliph was detained, questioned, and flung into HMP Belmarsh. Inside, his fellow inmates alleged that he was beaten by the prison officers and injected with “stuff.” One inmate recalls him being wheeled in during the Friday prayers and “seemed to be having problems with his mental health.” In fact, it was inside Belmarsh that he announced that he was no other than the awaited apocalyptic savior, “the Mahdi,” ready to aid Jesus upon his return. Many of his followers, in a strange irony, excommunicated him and he emerged from prison resolved to live a life of seclusion.

But, occasionally, there were flashes of the old self. When Rifai was asked about traveling to Syria in 2012 to “help,” he gave his blessing to the venture. Abu Omar, too, heard and obeyed. He took his family to Atmah, a Syrian refugee camp, kitted up a praetorian guard known as the Soldiers of the Caliph, and quickly built up a reputation for extremism. While there, even as ISIS was taking over in 2013, Abu Omar declared that the ailing caliph was coming – he was just preparing his travel documents (presumably the ones he had burned in front of Regent’s Park Mosque). Rifai passed away in 2014 before making the arduous journey. Abu Omar continued his career in ISIS, linked to massacres, intra-jihadist infighting, and getting involved in theological debates which resulted in al-Baghdadi’s excommunication and Abu Omar’s subsequent execution. Unlike Abu Omar, many other followers of Rifai continued to serve the ISIS caliphate faithfully.

Rifai represented a feeling that defied political reality: that the ills of the Muslim world could be solved by the return of the caliph. That same emotion saw thousands of Muslims from all corners of the world flock to ISIS. And arguably, that feeling will result in future attempts to revive the institution.

The fact that al-Baghdadi’s caliphate replicated many of Rifai’s actions suggests that despite the pitfalls Rifai faced, his ideas were far from an aberration. His caliphate did not need an Iraq war to incubate. Rather, Rifai was a manifestation of Sunni emotional angst emanating from a Muslim world still grappling with its place.

The idea of the caliphate is, of course, larger than one man, and calls for its return will not go away. As the Uyghur Muslims in China are being systematically eliminated, one Facebook post lays out the case: “The solution is to remove these rulers and unite Muslims behind one Khaleefa, one Army, under the flag of Islam and stand in defense of the Uyghurs …” When the Hagia Sophia was re-converted into a mosque, the pro-government paper Gercek Hayat called on Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to re-establish the caliphate. “If not now, when?” it pled. “If not you, who?”