After more than two months of arduous toil, a middle-aged man with tattered clothes and bleeding feet finally stands before the gates of the ancient city. His drained appearance belies the tranquility he feels inside, running down to the very depths of his soul. “How long does one have to travel to find oneself?” he wonders, and “Why was it necessary to undertake such a journey simply to move from one side of one’s heart to the other?” The seeker stares in awe at the majestic walls of Damascus, revered for keeping out the invading hordes that stood before it in siege for 20 long years. But alas, he realizes, “no walls are more impenetrable than those of the heart!” And will history remember someone who strove for 20 years so that his heart might finally open to the light?

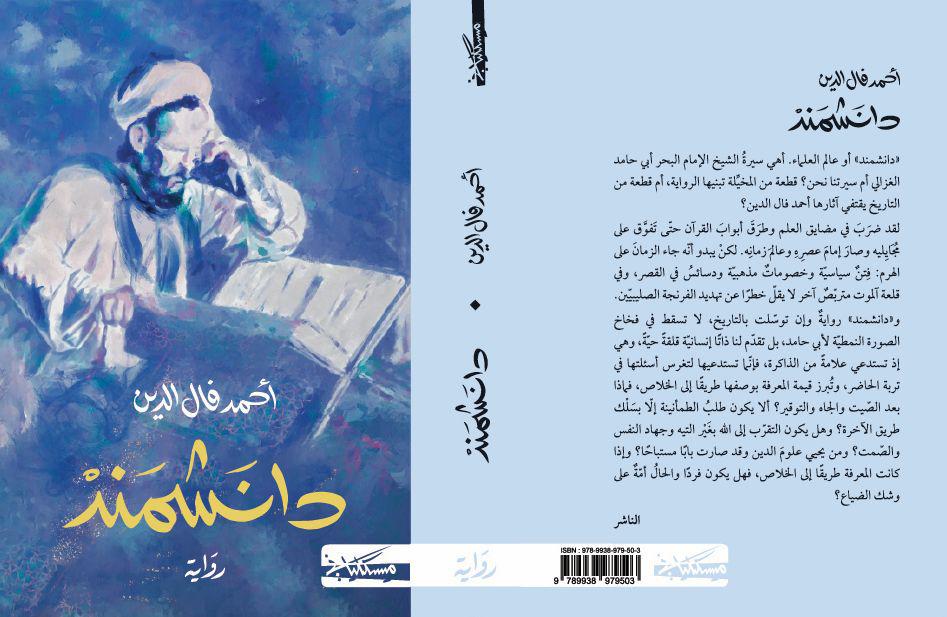

With this enticing opening scene, Ahmed Vall Dine’s latest novel takes the reader on a journey into the inner world of one of the most celebrated figures in Islamic history: the 12th-century philosopher and spiritual savant, Abu Hamid al-Ghazali. Vall Dine is a veteran correspondent for Al Jazeera, but the Mauritanian writer’s interests stretch beyond the newsroom and deep into the archive, bridging the present with the past. “Danishmand” (“The Wise Master”) is his fifth book; his first — published in 2012 — was an autobiographical account of his incarceration in Moammar Gadhafi’s prison cells during the Arab Spring. (The English translation, “In Gaddafi’s Clutches,” has just been published by Dar Arab in the United Kingdom.) The 2012 memoir was followed by two novels in quick succession, published in 2018 and 2019. In 2021, Vall Dine returned to his journalistic roots and published a book-length essay on the rise and fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Poetry has always been regarded as the repository of Arab historical memory; it is the “Diwan al-Arab.” Still very much appreciated among Arabic speakers, poetry is nevertheless no longer the dominant form of literary expression. The Arab world’s encounter with modernity not only introduced new forms of living, but new forms of literary expression as well, and the historical novel has rapidly gained prominence in modern Arabic literature. Contemporary Arab writers have increasingly embraced the genre to revisit the past, but it finds its best expression when the creative reimagining of the past is effectively utilized to stimulate reflection and offer commentary on the present.

With “Danishmand,” Vall Dine once again returns to the historical fiction genre and reimagines a tumultuous chapter in the Islamic past in a way that makes us think about our present predicament. In his first foray — “Al-Hadaqi” (2018) — Vall Dine explored the life and times of the ninth-century Iraqi polymath Abu Uthman Amr ibn Bahr al-Jahiz, who lived and wrote in the Abbasid Golden Age. Al-Jahiz is still revered and widely read in the Arab world today but remains an obscure figure in Anglophone literary circles, enjoying the attention of only a small group of academics and scholars of Arabic literature.

In contrast, al-Ghazali is arguably one of the most scrutinized figures in the Islamic intellectual tradition and is equally renowned in the West. His works were translated and studied in Latin Christendom, and while he is fortunately not one of the five Muslims confined to hell in Dante’s “Inferno,” he is mentioned in the “Convivio,” the Florentine poet’s reflection on the various disciplines of knowledge prevalent in his time. Rene Descartes, the 17th-century father of modern epistemology, is believed to have possessed a Latin translation of al-Ghazali’s autobiography, “The Deliverance From Error” (“Al-Munqidh min al-Dalal”), which was annotated in his own hand. On this basis, historians of philosophy have suggested that Islamic thought influenced European philosophy well beyond the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Al-Ghazali’s books still enjoy wide circulation, and countless studies have been written on his life and thought, including novels (in Arabic and Persian). To this respectable legacy, Vall Dine now adds another work of historical fiction, carefully composed in consummate Arabic prose.

Apart from the opening prologue that is set in the middle of the story — on the brink of the looming quest — the book unfolds chronologically, following the life trajectory of the young orphan boy, Muhammad, from the dusty streets of the small town of Tabaran in the district of Tus, in 12th-century Khorasan, to the major centers of Nishapur, Isfahan, Baghdad, Damascus and Jerusalem. The unfolding narrative ultimately follows the path back to the final resting place of the wise master in his hometown in northeastern Iran, not too far from present-day Mashhad.

Part 1 of the novel — “Al-Yatim” (“The Orphan”) — opens with two young boys, Muhammad and his brother Ahmad, striving to scratch out a meager existence along with their recently widowed mother. Their father has left a small inheritance for the boys’ education with a loyal friend, but these funds have been depleted and the dying man summons them to discuss their future. The family friend expresses regret over not being able to provide for them himself due to his own state of abject poverty and failing health. Nonetheless, he has found a way for the boys to receive a religious education, one that will provide for them materially and fulfill their deceased father’s wish for his sons to become scholars. He arranges for them to be enrolled at a religious seminary that provides food, accommodation and clothing for its students. On weekends, the boys are able to visit their mother, now relieved of the burden of providing for her sons. The young Muhammad’s prodigious intellect instantly sets him apart from his peers and his teachers predict a bright future for him. In time, Muhammad is able to secure a scholarship to study at the great Nizamiyyah Seminary in Nishapur, under one of the foremost scholars of the age, Abu al-Maali al-Juwayni.

In the second part of the novel — “Danishmand” (“The Wise Master”) — the precocious student has grown into a great scholar whose reputation begins to rival that of his recently deceased teacher, al-Juwayni. His success draws the attention of the great Seljuk Vizier Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ali Tusi, known by the honorific Nizam al-Mulk (“Organizer of the Realm”), founder and patron of the eponymous Nizamiyyah schools. Al-Ghazali is thus drawn into the world of politics and court intrigue. The caliph in Baghdad is no more than a titular figure: True power resides in the hands of Seljuk Sultan Malik Shah, son of the great Alp Arslan. Nizam al-Mulk served Alp Arslan and pledged loyalty and service to the murdered sultan’s 19-year-old heir. Now, almost two decades later, the Seljuk realm is relatively secure and Nizam al-Mulk is at the height of his influence. There are nonetheless always pretenders to the throne, and the powerful esoteric sect of Assassins led by the enigmatic Hasan-e Sabbah — the Old Man of the Mountain — is determined to usurp power from the Seljuks. The assassins are Shiite Ismailis — loyal to the Fatimid caliph in Cairo — and wreak havoc in the Islamic East through a concerted campaign of killing, targeting leaders and scholars.

By now the Danishmand has joined the entourage of the great vizier, written a book refuting the creed of the Ismailis and served as an emissary of the court on numerous occasions. Nizam al-Mulk appoints al-Ghazali to teach at the Nizamiyyah in Baghdad — the most important of his schools — located in the cultural and intellectual capital of the Islamic world and in close proximity to the court of the Sunni caliph. The Seljuk Empire is thrown into chaos shortly thereafter, when Nizam al-Mulk is assassinated during Ramadan in 1092. His murder is followed by the sudden death of Sultan Malik Shah a month later. Malik Shah’s sons are instantly dragged into an internecine battle over the throne, and al-Ghazali is inadvertently drawn into their power struggle, acting as an emissary among the rival heirs, their mothers and the caliph.

When the caliph dies two years later, al-Ghazali abruptly abandons his teaching post and flees into self-imposed exile. The third part of the novel — “Al-Harib” (“The Escapee”) — thus begins with the famous scholar exchanging the luxurious garments of the court for the coarse apparel of an ascetic traveler, setting off on the road to Damascus and simultaneously taking the first steps toward self-discovery. The third part thus takes off from where the novel began, and we now get a clearer sense as to why the author refers to the prologue as a rebirth (“Al-Milad al-Thani”).

In Part 4 — “Al-Nasik” (“The Ascetic”) — we accompany the seeker as he navigates the pathways of his newly discovered soul. In the closing part of the novel — “Bi Qalb Salim” (“With a Content Heart”) — we return to Tabaran, the final resting place of the Danishmand. The Wise Master has not only found contentment, but more importantly has also left behind a unique inheritance, a guide along the path that leads to felicity. His spiritual sojourn helped him produce his magnum opus, a work of genius ambitiously titled “The Revival of the Religious Sciences” (“Ihya Ulum al-Din”).

Vall Dine’s novel is a sprawling work that gives one much pause for reflection. Apart from its lyrical Arabic prose, the book is also characterized by the kind of thick description common in social anthropology, exploring the meanings of the plot’s events to its characters. His creative retelling of al-Ghazali’s life story is also very faithful to the documented history of the great scholar’s life and times. One has only to turn to Frank Griffel’s excellent study, “Al-Ghazali’s Philosophical Theology,” to get a sense of this. The first two chapters of Griffel’s book provide us with the most detailed account of the historical figure and draw on a variety of sources in both Arabic and Persian, the languages in which al-Ghazali wrote and conversed.

Vall Dine embellishes the historical record by paying admirable attention to detail and his portrayals of dress, social norms, book culture and culinary practices draw on historical sources and travelogues written in the period in which the novel is set. For example, samosas make an appearance at the Ramadan banquet hosted by Nizam al-Mulk just before he is assassinated. These mince-filled triangular pastries, popularly associated with Indian cuisine today, made their first appearance in the Persian chronicle “Tarikh-i Bayhaqi” (“Bayhaqi’s History”) by the 11th-century Khorasani historian Abu al-Fadl al-Bayhaqi.

While the novel is certainly illuminating in its grasp of social history, it goes much further, offering an enlightening perspective on the philosophy of history as well. Vall Dine goes against the grain of the common idea of history as unfolding along a single continuum leading to a perfect social order. While this idea of “the end of history” has been championed and popularized by Francis Fukuyama in recent times, the tradition stretches back to the early 19th-century German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and his philosophically grounded account of a linear history, ending at a point when society has reached its apogee and civilization is perfected.

The narrative thrust of the novel instead strongly affirms a cyclical conception of history, a theory clearly articulated by Abd al-Rahman ibn Khaldun, the 14th-century historian and social theorist. Ibn Khaldun poignantly stated that “Civilization is detrimental to societal development.” This unique insight emerged from the realization that the material affluence required to promote the pursuit of progress and the development of civilization would always be the exclusive preserve of powerful elites. The amassing of great fortunes by these elites is inevitably accompanied by the desire to maintain exclusive rights over such wealth, and, as such, the masses will always be left out in the cold. On the basis of this insight, Ibn Khaldun argued that the course of history is cyclical. Powerful civilizations reach a peak but ultimately collapse, because the path to power leaves too many stranded along the way.

In al-Ghazali’s epoch, Islamic civilization was still ascendant, and the contrast between the novel’s context and our own gives a compelling version of the civilizational cycle. The fact that Vall Dine is able to creatively reimagine the past in a way that stimulates us to think about the present is not only a strong indication of the maturation of the genre of historical fiction in contemporary Arabic literature but also an acknowledgment of the author’s mastery of his craft. Vall Dine does not have to openly lament Islamic civilization’s fall from grace; rather, he presents a cogent portrait of what it looked like in al-Ghazali’s era.

In the novel, Arab and Persian elites are at the top of the social hierarchy, with the Turkish military castes rapidly integrating into these ranks. The subaltern classes are made up of Byzantine slave girls prized for their beauty and groomed for service, similar to the court eunuchs castrated in Christian lands and sold into slavery to be trained as bureaucrats and keepers of the harems of powerful men. Similarly, the violent hordes threatening the realm are the white barbarians of Europe who have been mobilized by Pope Urban II and his cohort of religious zealots, setting out to reclaim Jerusalem for their faith. This portrayal of the European barbarian hordes — notorious for their bloodlust and aversion to bathing — marching on Jerusalem via Constantinople, where Christians were far more civilized, constitutes a compelling narrative strand that orders society into a clearly delineated civilizational hierarchy.

The detriments of high civilization are acutely felt by al-Ghazali, especially in relation to his scholarly peers who vie for attention and courtly prestige. Their immersion in material pleasures and pursuits has brought about a spiritual malaise. The “sharia,” or sacred Islamic law, has been reduced to no more than positive law, “fiqh,” a utilitarian jurisprudence defined by legal stratagems and hermeneutic flexibility. Stated in the language of our times, the Islam that al-Ghazali sees being practiced by his peers has effectively been secularized.

The Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor has convincingly argued that modernity is defined by an immanent frame, that is, a refusal to address any issues beyond the sensory world, meaning that we live in an era largely bereft of any transcendent grounding. Stated differently, our existence is dominated by secular time. Taylor therefore holds that modern society is defined by radical horizontality, where there are no high points and where we are no longer rooted to “something other.”

Al-Ghazali, too, developed an acute awareness that the world around him was flattening out, and he therefore sought salvation by attempting to reconnect with the divine. From this vantage point, his journey marks the traversing of the boundaries of secular time and a reentry into the realm of sacred higher time, which is why he appositely refers to the new Islamic discipline formulated in his magnum opus as the “Science of the Path to the Afterlife” (“Ilm Tariq al-Akhirah”).

Vall Dine has not simply written a work of historical fiction. By imaginatively documenting the life story of one of the most prominent sages in the Islamic intellectual tradition, he has effectively taken us along with al-Ghazali on his spiritual quest. On this journey, we learn that even a work of fiction is able to traverse the boundaries of the secular and deliver us into the realm of the sacred.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.