It’s a blistering late summer afternoon in Marsala, a city in western Sicily known for its windmills and cotton candy-pink sunsets over its salt pans. In narrow alleyways, the smell of fish broth drifts into the hot air, mingling with the clinking of terracotta plates and the murmurs of women’s voices coming from the balconies as they peel and chop vegetables, scale fish, and rub soft, moist grains of semolina between their palms to aerate them. It is Friday afternoon, which in Marsala means only one thing: couscous.

The dish is a tradition and an aberration — the national dish of Tunisia is as common in Marsala as it is in Mahdia, just across the short stretch of the Mediterranean that divides Italy’s southern island and the African continent. “I always wondered how no one ever questioned why couscous is as common as pasta here,” Rosa Maria Pugliese told New Lines as she worked the semolina by hand in her sunlit kitchen. “But it’s important to remember why that is, so people can be aware we were once the poor ones looking for a better life in the opposite direction.”

Pugliese, 71, may carry an Italian name, but she is one of tens of thousands of Italians born and raised on the opposite side of the Mediterranean, in Tunisia.

In the past decade, as Sicily has become the “Gateway to Europe” and the front line of Mediterranean migration, the narrative of foreigners flooding into Europe has become fodder for far-right governments — including that of Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s prime minister. Indeed, in that time, some half a million migrants, many seeking asylum, have landed on Sicily’s shores, according to data from the International Organization for Migration. Since its election in 2022, Meloni’s right-wing government has taken a particularly hard stance toward Tunisians, after a record 97,306 so-called irregular arrivals (that is, those who cross the sea in small boats and rafts and do not enter via passport control) were recorded in 2023 alone. Now, it rejects thousands of visa-seekers from its southern neighbor every year, including many students admitted to Italian universities. Yet the government’s position overlooks an inconvenient, unacknowledged sliver of history: A little over a century ago, it was Sicilians navigating those same migration routes — in reverse.

For millennia, the Mediterranean was the maritime highway of the old world, and Sicily sat right at its center. Travelers from east and west passed by or through it, leaving their mark. Long before European borders were drawn, the cultures, languages and genetics of the Mediterranean basin mixed, creating communities and subgroups that defy easy categories today. And so it is no surprise that fluid movement between Sicily and Tunisia has been a core part of Mediterranean history, extending far beyond the long-simmering rivalry between ancient Carthage and Rome, or the conquest of Sicily in 827 that saw the North African Aghlabid, Fatimid and Kalbid dynasties rule the island for over 200 years. (Their influence is still felt in the architecture of Palermo’s great monuments, including its cathedral.)

Even after the expulsion of Muslims by European Christian armies in 1071, the exchange of people between the northern and southern coasts didn’t stop. If anything, it grew stronger throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, after the Berber sultan Mulay Ahmad gave the island of Tabarka, off modern-day Tunisia’s northwest coast, to a Genoese family to fish for red coral, a highly sought-after commodity that had been the object of bitterly disputed fishing privileges in the western Mediterranean. The coral trade soon linked the northern and southern Mediterranean even more closely.

Through more intense trade exchanges and piracy, the socioeconomic ties between the two shores continued. Those trade relations made Tunisia a prime destination for Sephardic Jewish merchants from the Tuscan city of Livorno, who were seeking safe shelter after expulsion campaigns in the 16th and 17th centuries. Those exiles sought refuge in the Ottoman Empire and eventually settled in Tunis, where they formally established a flourishing, well-integrated community in 1685.

“Tunisians like to say that Italians are their Mediterranean cousins, sharing geographical proximity, similarities in food, gestures and physical features,” William Granara, a professor at Harvard University whose research focuses on Arab Sicily, told New Lines. “But there’s also a shared history that continued well after medieval times, and has mutually influenced local societies.”

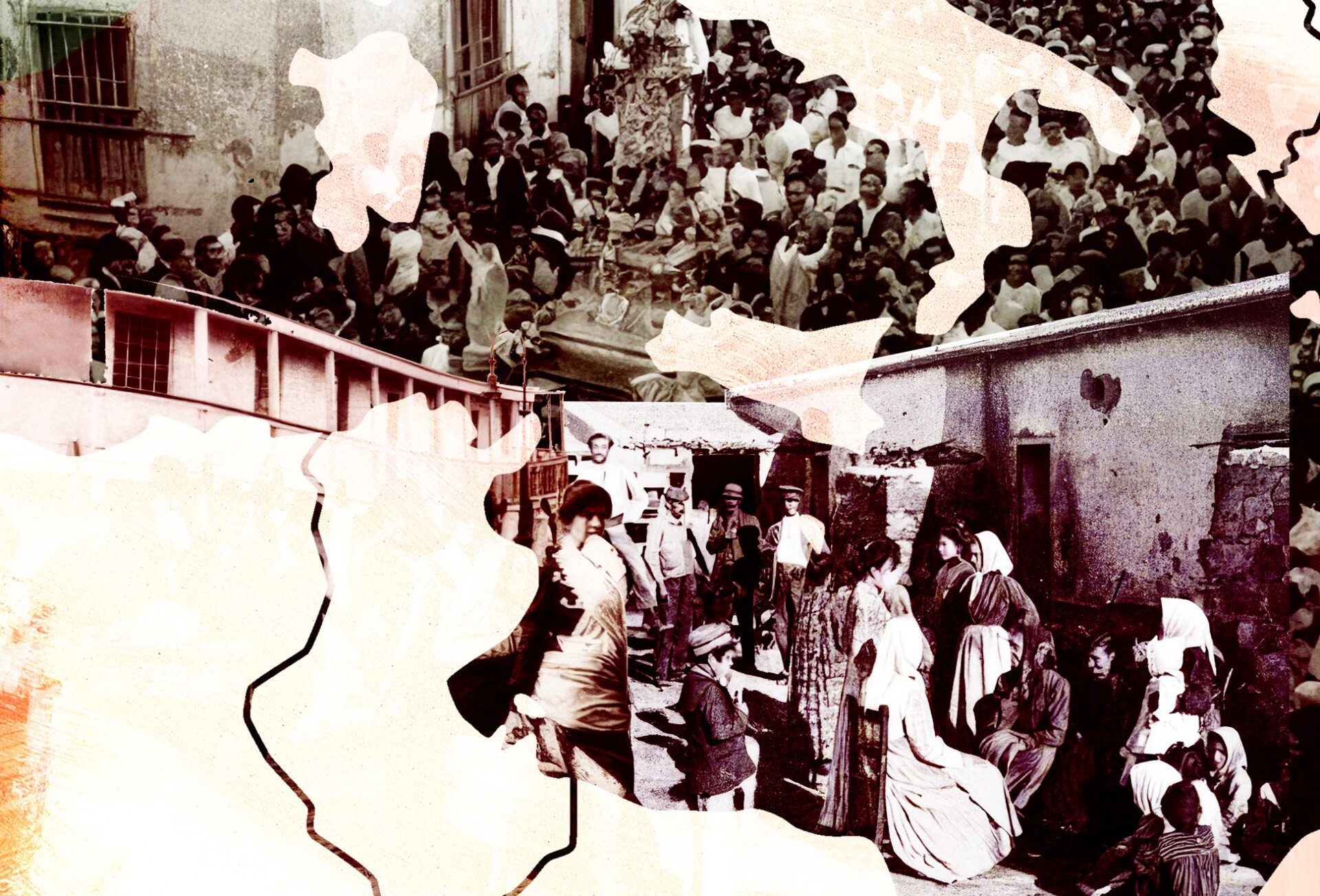

One of the strands of that history that has almost disappeared from memory happened at the end of the 19th century, when Italians, particularly Sicilians, headed to Tunisia in waves. Their influence would be felt for generations in the cuisine, architecture and even language of the nation that welcomed them.

The majority were artisans, farmers and mechanics fleeing Sicily to escape the mounting poverty and the rule of the Mafia after Italy’s unification — which began when Giuseppe Garibaldi, the Italian general considered one of the “fathers” of the state, took the city of Marsala. The consolidation left a political void in the south, leading to unemployment, criminality, land grabbing from the government and extremely high taxes that triggered a mass emigration toward what was, at the time, the richer and developing southern shore of the Mediterranean.

By 1925, almost 80,000 of about 130,000 Italians in Tunisia were Sicilians, coming mainly from the western provinces of Trapani and Palermo.

The generations of touchpoints leading up to the migration made for a soft landing. Decades before, Tunisia’s ruler Ahmed Bey, whose mother was a Sicilian Christian, allocated land for the building of a church for the tens of thousands of Sicilians, as well as smaller numbers of Maltese, Greek and Spanish Christian worshippers who had begun to settle in the welcoming, cosmopolitan Tunisia toward the middle of the 19th century. But it was the Church of Saint Augustin and Saint Fidèle, erected in the late 1880s in La Goulette, the port district on the edge of Tunis where thousands of Sicilians had settled, that became the Italian cultural hub. To this day, the entire enclave shuts down every Aug. 15 for the procession in honor of Our Lady of Trapani, a patron saint of fishers whom the Sicilians coming from Trapani, a port town on the western side of the island, brought with them.

“What we remember the most after so many years is the peaceful coexistence among various ethnicities. Jews, Muslims, Europeans, we all celebrated each other’s festivals or collective defeats,” Marinette Pendola, a Sicilian novelist who was born in Tunisia, told New Lines. “It wasn’t ‘Tunisians and the others.’ We were all together.”

According to Granara, the Harvard professor, the history of the Italian minority in Tunisia has largely been neglected — by communities in both countries as well as in academia. He believes that is because, despite the size of the migration wave, the Italian presence wasn’t a colonial occupation, but sat somewhere closer to a migratory workforce, thanks to a geopolitical mishap for Italy at the beginning of the 20th century.

With the gradual crumbling of the Ottoman Empire, Rome had eyed Tunisia as it plotted a Greater Italy, and identified the Sicilian settlers as a potential aid to overseas expansion. But then France took control over Tunisia without Italy’s approval, in a move remembered by Italians as “the slap of Tunis,” and Rome’s plans fell apart. The French occupation became a symbol of Italians’ colonial inferiority and brought Sicilians closer to the Tunisians, as victims of the same higher power.

Mohamed Benahmed, the founder and president of the Tunis-based association La Piccola Sicilia (an Italian name meaning “Little Sicily”), explains that, unlike the French, who imposed themselves through a military occupation in Tunisia, the Italians were perceived to be of similar social and economic status, working humble jobs side by side with locals and integrating within Tunisian society, learning the local dialect and living in poorer neighborhoods. “They were like the Tunisian immigrants in Europe today,” Benahmed said with a knowing laugh. He spent much of his adult life as one of the 120,000 Tunisians living in Paris. “We Tunisians like to joke that our country was an Italian colony managed by the French. That’s because the Italian population was larger than the French, but they were well-integrated and not acting as a superior ethnicity pretending to dominate us.”

Benhamed moved from downtown Tunis to the suburban neighborhood of La Goulette — also often called “Little Sicily” — in 2017, because he wanted to act against the mounting gentrification that was wiping out the Italian architecture of the area in favor of modern condos and updated, streamlined storefronts. “This is also part of our heritage, and I feel sorry we’re not doing enough to preserve it,” he said. That’s why in 2021 he founded La Piccola Sicilia, with the hope that spreading knowledge about this forgotten history would help preserve the neighborhood’s fading urban gems through preservation projects.

On a wall along a side street in La Goulette, the great Italian actress Claudia Cardinale is immortalized in a mural. Cardinale, who became a breakout star with her turn in Luchino Visconte’s 1963 film adaptation of “The Leopard,” the historical novel by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa that chronicles 19th-century Sicilian life, was born and raised in Tunisia, the daughter of Sicilian immigrants. In fact, when she was cast for “The Leopard,” she had to be dubbed, because at the time she only spoke Tunisian Arabic and Sicilian, not Italian.

“Perhaps because of nationalism, the stories of European minorities in Tunisia haven’t found much echo,” Benhamed said. “But they’re part of our cosmopolitan past, and it’s a disservice against our own society to obliterate that history, because it would’ve been beneficial to prove how we were once the ones welcoming immigrants running away from poverty and giving them a home and job opportunities, while today we don’t get that same treatment.”

A few years earlier, and on the other side of the Mediterranean, Francesco Tranchida, a local Marsalese with no blood ties to Tunisia, founded the Marsalese Memory Bank, an association collecting oral history accounts of local citizens. That included Sicilians of Tunisia, hundreds of whom began to return in the 1960s.

“I began digging into archives and data, and that’s how I found out that by 1901, 7,000 of my fellow citizens were living on the southern shore of our sea. I thought it was fascinating and had the motivation to try and map this phenomenon to fill a knowledge gap,” Tranchida told New Lines. For three years, Tranchida collected oral histories from Sicilians of Tunisia who had returned to Marsala, like Pugliese. The project snowballed, and Tranchida sought out ways to revive the community more concretely, rather than just preserve its memory. It has now morphed into an annual gathering that brings together Sicilians of Tunisia scattered around Europe. The event, which had its fourth iteration in September, took the name of “Matabbia,” which in Tunisian- inflected Sicilian means “hopefully,” similar to the Arabic “inshallah.” Tranchida explained that the word refers to a hopeful message, tackling the collective amnesia of their past, but also celebrating the future of Sicilian-Tunisian relations.

When Tunisia gained independence from France in 1956, local nationalist movements portrayed all Europeans as a foreign presence deserving of hostility. Even though Sicilians had long been largely considered of the same social and political milieu as the Tunisians under French rule, many soon felt a creeping sense of being shown the door as Tunisians were given priority in public jobs and landownership. The independent government forbade any forms of “Italianness,” even going so far as to suspend the Virgin of Trapani procession, which was only reinstated in 2017.

“Young nations can be very jealous of their own history,” said Pendola, who left her hometown of Zaghouan at age 13 and returned to her ancestral homeland with her family. “Even though we were part of that history, we felt the pressure to leave.”

Within five years of independence, most Italians had left in a self-imposed exile, and many artisanal jobs they dominated — from typography to upholstering — were largely lost or greatly diminished.

Ironically, around the same time, a demand for skilled fishers, caused by a shortage of Italian labor in the south due to emigration toward northern Europe, pushed a mass influx of Tunisians from the coastal towns of Chebba and Mahdia toward Mazara del Vallo, in the province of Trapani in Sicily. Mazara, the site of the initial battles of the Arab conquest, had deep ties to Tunisia, because many Sicilian immigrants had set off from there for Tunisia a century earlier.

The unprecedented influx created the oldest Tunisian community in Italy, and a mirror image of the Sicilians in Tunisia of 100 years before: migrants deeply enmeshed in local life, but guarding their own traditions and identities. Of the 100,000 Tunisians who now reside in Italy, around a quarter live in Sicily.

Pugliese returned to her ancestral homeland around the same time, but the landing was far from soft. Much like the Italians expelled from Moammar Gadhafi’s Libya, who ended up in refugee camps in Italy, the reception of those returning from Tunisia was decidedly frosty.

“Not only were we eradicated by circumstances from what we rightfully considered our homeland, but in Sicily we were seen as Tunisian immigrants stealing jobs,” Pugliese lamented. She said that for years she nursed an identity crisis that made her feel a sense of belonging to both sides and neither at the same time. She felt alienated at school, and she never quite fit in socially in Italy.

“Not everyone is aware of this history, so initially I encountered lots of curiosity when I came back. People would ask me about my family’s past,” she said. “But after a while, you find yourself alone with your memories, because we have such an odd status, it’s hard to relate to. Some identified us as Arabs, and therefore Muslims, others with a shameful colonial past we didn’t even experience.”

Pendola also experienced a similar shock at the age of 13, when the land her family had farmed for three generations in Zaghouan was given over to Tunisians, and the family returned to a homeland she had never set foot in.

“We chose not to go to Sicily. We had no more relatives there, and in terms of employment, the island couldn’t offer us a future,” Pendola recalled. “We spent three months in a refugee camp. I remember not being able to explain my origins to my classmates, of whom I was jealous because they had always stayed in only one place. Only now that I’m old can I see my past in between two shores as a strength rather than a handicap.”

It took her several decades to process the grief of her lost homeland. Much of her healing came through writing a series of partly autobiographical novels about the Sicilians of Tunisia. They, along with Tranchida’s oral history archive and the documentary “Italians of the Other Shore” by Giuseppe Favaloro, make up the bulk of the record of this fading history that isn’t taught on either side of the sea.

Abdelkarim Benabdallah was born in 1975 and says that his whole generation grew up with the sounds of Italian newscasts floating through their living rooms if the satellite signal was strong enough. “Almost everyone in Tunisia speaks at least some Italian,” he told me, in Italian with a soft Sicilian accent. “At school, though, we never learned about Sicilian, and Italian, immigration to Tunisia. We only focused on the Muslim conquest of Sicily, which departed from Tunisia, or Tunisian resistance against the French colonizers, a narrative that put us in a powerful role in history.” He said he dug into the history of the Sicilian community by himself, when he moved from the countryside to Tunis in 2001. It’s a pity, he added, because despite the recent crackdown on Tunisian migration to Italy, Tunisians have always perceived Sicilians as brothers — and still do — and learning about this shared humble past would only increase empathy toward each other.

“The ones who do make it to the other side and settle in Sicily tell us they have no problems integrating. We know that the rejections come from a bigger Fortress Europe plan, that it’s nothing personal,” Benabdallah said.

Three years ago, Pendola returned to her native Zaghouan, where Benabdallah also grew up, for the first time since she left some 60 years earlier. She saw the remnants of her former home in the Tunisian countryside. An old neighbor recognized her as “Bint Mariano” — Mariano’s daughter. It brought her to tears.

She feels deeply the current unfairness of borders and the restricted movement between two shores that, until 100 years ago, freely exchanged people and traditions. Pendola believes that the history of her community could help change perspectives. “In the current antimigration climate, it’s particularly important to keep these stories on the radar of ordinary people,” she said, “to understand the reasons behind those who cross the Mediterranean by boat in search of a better life.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.