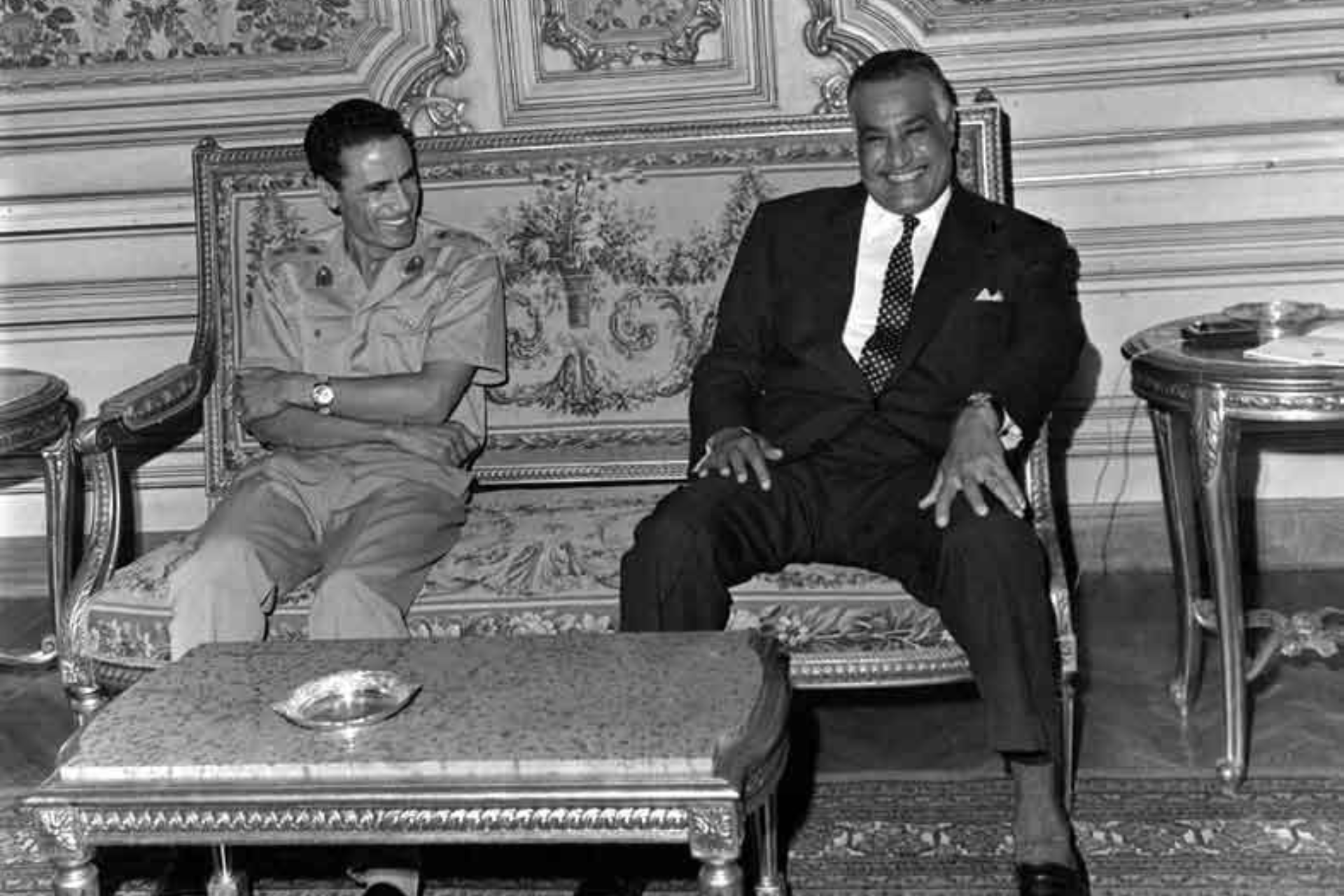

An audio recording of a colorful and little-known conversation between the late Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser and his Libyan counterpart Moammar Gadhafi in 1970 has been widely shared and discussed in the Arab world in recent days, sparking a lively debate on Nasser’s legacy and the wider history and politics of the decades-long Arab-Israeli conflict.

In the audio, Nasser appears to distance himself from the Palestinian cause and criticizes other Arab leaders for pressing him to wage war against Israel, rather than seek peace with it diplomatically, as he was doing at the time. Posted on a YouTube channel linked to Nasser’s son, Abdel Hakim Abdel Nasser, on April 25, the 18-minute recording was then picked up and republished by major Arab media outlets, including BBC Arabic and Saudi Arabia’s Al Arabiya, and written about in leading Arab newspapers, not to mention on social media.

“Today they say, ‘It’s either all of Palestine from the river to the sea, or none of it!’” complains Nasser to the young Gadhafi in the conversation, which took place in Cairo’s Qubbah Palace on Aug. 3, 1970 — less than two months before Nasser’s death by heart attack at the age of 52. Six other senior Egyptian and Libyan officials were also present.

“OK, let’s say, ‘We’re going to liberate’” Palestine, Nasser continues. “It will be like 1948, we won’t liberate or do [anything]. I’m sorry to speak bitterly. [But] who will liberate the West Bank? That would mean we give the rest of Palestine to the Jews. Is that what anyone wants?”

When Gadhafi counters that war is unavoidable because the fight against Israel is “existential,” Nasser interrupts: “When will we fight? Where will we get weapons from? … How do you liberate Tel Aviv? The Jews are stronger than us, I’d like to tell you; stronger on land, stronger in the air, despite all we’ve done and spent. Even in tanks, they’re superior, in planes, in artillery. … I don’t say this because I’m defeatist, I say it because if we want to achieve a goal, we have to be realistic and know how to achieve it.”

At another point, Nasser says that if he were Jordan’s King Hussein, he would agree to keep the West Bank demilitarized, if that were Israel’s condition for returning it to the Hashemite kingdom. “How [else] is King Hussein going to get it back?” As for the armed Palestinian factions hoping at that time to topple Hussein and seize power in Jordan themselves, Nasser quips: “If only! … If they took power, they would become people with responsibilities before them. How would they liberate the West Bank?”

Nasser then offers Gadhafi a sarcastic — or half-sarcastic — proposal: “You go to Baghdad. … We’ll stay away from it all, you leave us to our defeatist, surrenderist peaceful resolution, I can handle that with a clear conscience. Go for it, whoever wants to fight [Israel] … Syria wants to fight, and what’s his name, [Palestine Liberation Organization leader] Yasser Arafat, and [Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine leader] George Habash, and [Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine leader] Nayef Hawatmeh, go get them.” Gadhafi laughs. “And get [Iraqi President] Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, and [People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen President] Salem Rubaya, and you want to fight, and go also to Algeria and get [Algerian President Houari] Boumediene to go and fight. … We’ll agree with [United Nations Special Envoy Gunnar] Jarring, we’ll talk only about Sinai, we’ll have nothing to do with the Palestinian cause, nor the secure borders, nor anything else, we’ll speak only about Sinai.”

Fascinating though this candid and intimate chat between two key figures of modern Middle Eastern politics undoubtedly is, it’s equally interesting to consider why it has garnered as much attention as it has at this particular time. That so many apparently regard it as a scandalous revelation of something previously unknown points, among other things, to an enduring gap between public perceptions of Nasser and the actual historical facts of his life and political record. Disentangling the man from the myth requires a few clarifications.

For a start, despite being misreported by some media outlets as a “leak,” the conversation in question had already been freely available for years on the website of Alexandria’s public library, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina, which hosts an extensive archive of Nasser-related material donated by his family. (So intense has been the furor that the library has felt compelled to issue a statement clarifying that it was not responsible for the clip’s publication on YouTube.)

Moreover, it is no secret that Nasser was pursuing a diplomatic resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict in 1970, or that this fact had caused his relations to sour with the rulers of states like Syria, Iraq and Algeria, as well as the heads of leading Palestinian factions. Three years earlier, in November 1967 — shortly after Israel’s staggering victory in the Six-Day War, which saw it capture the entirety of Jerusalem, the West Bank, Gaza, the Syrian Golan Heights and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula — Nasser formally accepted U.N. Security Council Resolution 242, which acknowledged Israel’s “sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence” and “right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force.” This was a remarkable U-turn for a man who, just six months earlier, in a speech on May 26, had vowed to “destroy” Israel. Resolution 242 also called on Israel to withdraw from the territories seized in the Six-Day War and facilitate a “just settlement” of the Palestinian refugee issue, thus establishing the so-called “land for peace” formula that has been the basis of most diplomatic initiatives aimed at a peaceful solution in Israel-Palestine ever since.

Arafat’s PLO, which refused at the time to recognize Israeli sovereignty on any part of historic Palestine, rejected Resolution 242, as did states such as Syria, Iraq and Libya. A rift thereby solidified between those who opposed the resolution and those who endorsed it, the latter including Nasser, Jordan’s King Hussein and the Lebanese government.

But Nasser didn’t stop there. In 1970, he redoubled his support for a two-state solution, publicly agreeing to a proposal by President Richard Nixon’s secretary of state, William P. Rogers, to cease fire against Israel and resume peace talks on the basis of Resolution 242. In a speech on July 24 that year — less than two weeks before his conversation with Gadhafi — Nasser said, “We have declared before the whole world that we seek peace.”

That was too much for the PLO, who responded with furious street protests outside Egyptian embassies in Jordan and Lebanon, at which Nasser was denounced as a “traitor,” “coward” and “agent of imperialism.” The livid Nasser retorted by closing down PLO radio stations in Cairo and halting the funding and equipping of Palestinian militants in Gaza.

This was the immediate context of Nasser’s discussion with Gadhafi at the Qubbah Palace. So poor, indeed, were his relations with the PLO at the time that he speculated to Gadhafi that a Palestinian militant might assassinate him: “The fedayeen could come and kill me, someone from the Palestinians, over this. I tell you, this is real. They say, ‘Abdel Nasser betrayed [us] and gave up the cause of Palestine’ and I don’t know what. There may even be Egyptians who agree. [But] I know what I’m doing and I’m convinced of what I’m saying.”

There is not actually much that is particularly novel or groundbreaking in the recording, then, at least not from the historian’s perspective. As one of Egypt’s leading scholars of Nasser, professor Sherif Younis of Helwan University, wrote on Facebook: “To those surprised by the content of the videos and audio recordings that circulated recently of Abdel Nasser after the 1967 defeat, I would like to say there is nothing strange or surprising in [them], not just for me, but for anyone who knows the basic facts (not the details) outside the nauseating political feuding and bickering between Nasserists and Sadatists” (that is, partisans of Egypt’s President Anwar Sadat, who made peace with Israel in 1978). After citing Resolution 242 and the aforementioned Rogers Plan of 1970, Younis added: “Egypt, in the Abdel Nasser era, [also] entered indirect negotiations for the resolution of the Palestinian cause, mediated by the United States, once in 1955, when it was called the ‘Alpha Plan’ in America, and once in 1963 in the [President John F.] Kennedy era. Both failed, but what’s important is that the principle of accepting the existence of Israel, albeit with certain conditions, was accepted at all times by the Egyptian state.”

One could go further. By Nasser’s own admission, as detailed in his book “The Philosophy of the Revolution,” Nasser met with an Israeli military officer, Yeruham Cohen, to discuss a truce during the war of 1948-49, when Nasser was besieged with other Egyptian troops near a Palestinian village northeast of Gaza. Nasser’s account of the meeting is curiously free of any ill will toward Cohen. On the contrary, Nasser quizzed him with interest about Israel’s successful “struggle against the British” and “secret resistance movement” under the former British Mandate authorities in Palestine. An Israeli account of the same meeting claims Nasser went as far as to tell the Israelis present — who reportedly included the future Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin — that Egypt was fighting “the wrong war against the wrong enemy,” and would have been better off staying out of Palestine and focusing on its own liberation from British occupation.

There is nothing all that inconsistent or out of character in what Nasser said to Gadhafi, in other words. But, of course, the history is perhaps beside the point, and the reaction to the recording may tell us more about contemporary politics in the Middle East than anything else. Never exactly uncontroversial at the calmest of times, the question of peace with Israel has become exponentially more contentious since October 2023, in light of the devastating war in Gaza, which many Arabs regard as outright genocidal. On social media, some have seen the Nasser recording as offering ammunition to the Arab states that have made peace with Israel — so much so that one user quoted by BBC Arabic, Mohamed Shaheen, alleged that Egypt’s intelligence agencies were behind the clip’s release, in order “to silence the Nasserists and tell them no one can object to [President Abdel Fattah] el-Sisi when he sells Palestine.”

The clip has also found favor with those who hold the Palestinian group Hamas itself responsible for the ruin of Gaza, who draw comparisons between the calamitous aftermath of its attack on Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, and Nasser’s crushing defeat in 1967. Writing in Asharq Al-Awsat newspaper, the Saudi columnist Abdulrahman al-Rashed wondered if we might someday hear a similar recording of the late Hamas leader and mastermind of the Oct. 7 assault, Yahya al-Sinwar, expressing the same sentiments as Nasser.

The conversation has, indeed, something for everyone. In Jordan — which made peace with Israel in 1994 — the revelation earlier this month of an alleged plot involving Hamas-linked militants, who were said to have been planning rocket and drone attacks inside the kingdom, will have added a sense of timely relevance to the Nasser audio. In Lebanon, where Hezbollah militants and their allies — including Hamas — fought their own war with Israel after Oct. 7, leading to the destruction of Hezbollah’s leadership along with much of the country, which remains occupied by Israeli forces to this day, the Nasser recording has been viewed through the lens of the lively national debate over disarming Hezbollah and the remaining Palestinian factions in Lebanon, and perhaps even moving toward official normalization and eventual peace with Israel. In Syria, too, there have been reports in recent days that President Ahmad al-Sharaa is prepared in principle to normalize ties with Israel. And, of course, there remains the lingering question of if and when Saudi Arabia might follow its Gulf neighbors Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates in joining the “Abraham Accords” and signing the “deal of the century” with Israel, something U.S. National Security Advisor Michael Waltz recently described as a “huge priority” for Donald Trump’s administration. It is the confluence of all these factors that has made Nasser’s “intervention” in the debate, as it were, so singularly combustible.

The late Jordanian-Syrian Baath Party leader Munif al-Razzaz once complained that it was impossible to think about any issue in the Arab world without taking into account the opinion of Gamal Abdel Nasser. Apparently, that remains as true today as ever.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.