Hosted by Joshua Martin

Featuring Alex Rowell

Produced by Finbar Anderson

Listen to and follow The Lede

Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Podbean

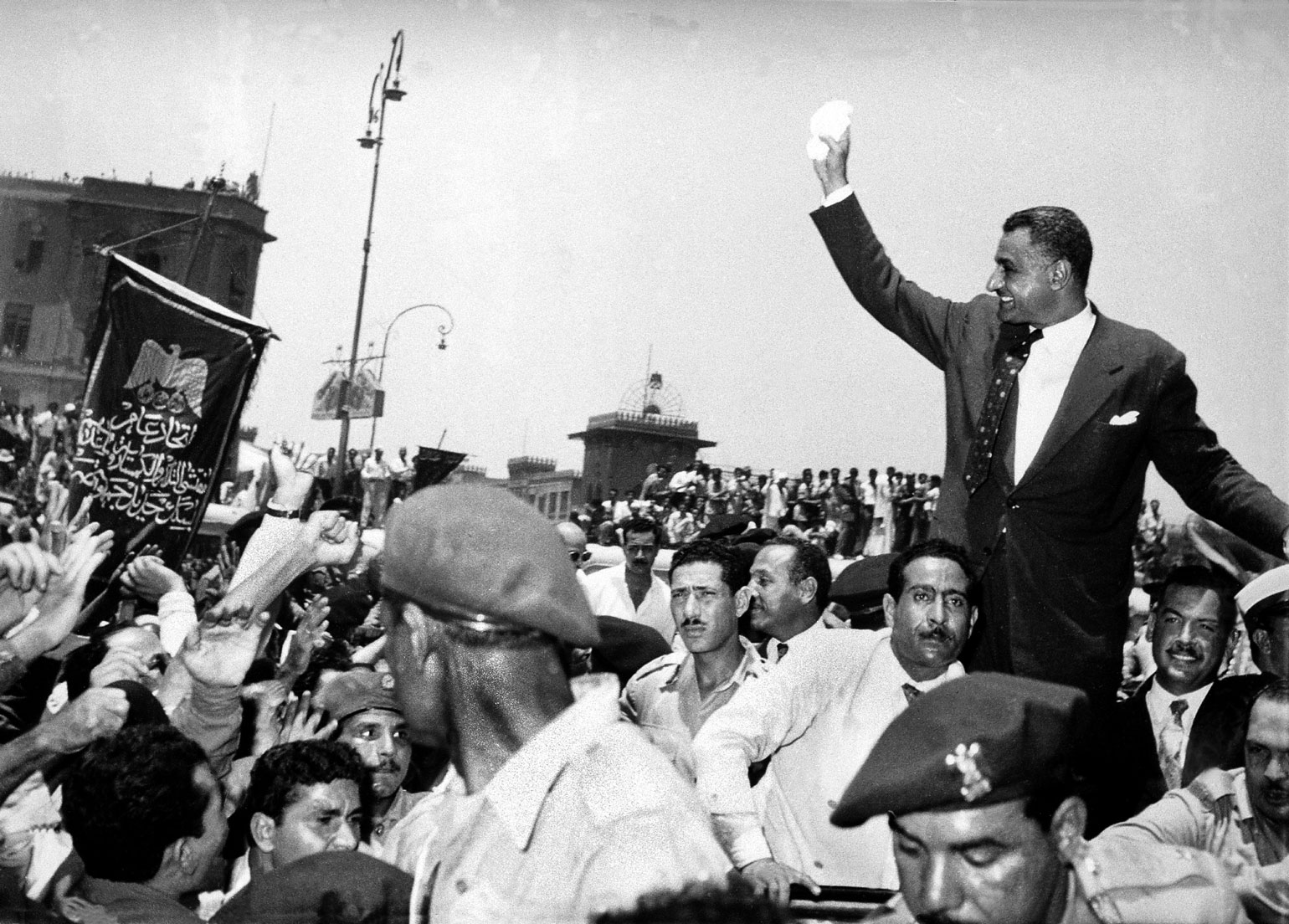

For Alex Rowell, the need to reassess the legacy of former Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser has only increased in the decades since the death of the hugely influential figure, and especially recently.

“If you just take a moment to look at the Arab Spring and the countries in which the largest protests occurred, and the regimes against which millions so courageously rose up … they were precisely the regimes that were the most direct legacies of Nasser’s time in power,” Rowell, New Lines’ online editor and author of “We Are Your Soldiers: How Gamal Abdel Nasser Remade the Arab World,” tells Joshua Martin.

“If you just take a moment to look at the Arab Spring and the countries in which the largest protests occurred … they were precisely the regimes that were the most direct legacies of Nasser’s time in power.”

One of the difficulties of getting to grips with such a reassessment, Rowell explains, is pinning down exactly what Nasser stood for. “In the beginning, he and the Free Officers are a kind of Egyptian nationalist movement, what you might call ‘Egypt First,’” says Rowell. “Around the mid-1950s, he moves towards this pan-Arab nationalism that became so associated with his name. But that fizzles out around 1961 with the collapse of Egypt’s union with Syria, and they quietly dust that under the carpet and Arab socialism becomes the new state doctrine. And even that runs its course.”

This inconsistency of ideology, Rowell suggests, is a result of the extent of the success of the Free Officers’ coup, surprising even Nasser himself. “He’s a man who always has to be improvising the next big thing, the next grand ideology that is going to justify why I have essentially suspended democracy in this country that used to have a version of democracy,” says Rowell.

Moving to foreshadow any possible suggestions that Rowell himself might be, as he puts it, “another white guy, still pissed off about Anthony Eden,” Rowell clarifies that “all of the criticism in the book is based on that which has already been advanced by Egyptians and other Arabs themselves.”

Rowell also looks to counter criticisms of his own work, such as those by Professor Fawaz Gerges in The Financial Times, who suggested Rowell might have ascribed too much agency to Nasser. “I didn’t feel persuaded by the arguments he was making,” Rowell says. “The idea that America was playing these shady, shifty Cold War games and Nasser was simply a well-intentioned third-world national liberator who was contending with these forces that were more powerful than he could bear, and that somehow compelled him to gas women and children in Yemen, or blow up the prime minister of Jordan in 1960, or assassinate a journalist in Beirut … I just don’t see the link.”

Conversely, for Rowell, there is a very direct throughline from Nasser’s presidency to today’s world. “The Cold War is now long behind us,” he says, “but what has remained is the authoritarian police state, the lack of press freedom, the lack of all kinds of personal and civil liberties, the torture, the wars, the assassination, those are things that still plague the region to this day.”

Further reading: Hoping to Channel Nasser, Egypt’s Sisi Provokes a Backlash