Nurmemet Metturson does not know if his wife and children are alive or dead.

The 39-year-old fled Xinjiang in China’s far northwest in 2014 amid growing repression of the Uyghur and other Muslim minorities in the region. Many Uyghurs refer to this area as East Turkestan.

According to human rights groups, this has proliferated into an extensive network of prisons and internment camps, where more than a million Uyghurs and a smaller number of Kazakhs, Kyrgyz and other ethnic Turkic Muslims are believed to be held. Detainees undergo political indoctrination aimed at assimilating them into the dominant Han Chinese identity.

Metturson, a business owner who frequently made trips between Dubai and Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, knew he would soon be targeted by the Chinese authorities. “My friends kept telling me not to come back,” he recounts, sitting on the expansive turquoise carpet of a mosque on the top floor of the East Turkestan Federation offices in Istanbul’s Sefakoy district, where many Uyghurs have sought refuge over the years.

“They told me that anyone coming back from overseas is being imprisoned for long sentences, sometimes 20 to 25 years,” he says. Metturson eventually traveled to Turkey in 2016, and had planned to bring his family here to join him so they could make a new life for themselves. But a few months later, he lost all contact with them.

In the months that followed, his messages to his wife on WeChat, a Chinese instant messaging app, went unanswered. In 2017, when human rights groups exposed the existence of the internment camps, Metturson’s heart sank, wondering about the fate of his wife and four children, now aged between 6 and 12.

“Now I don’t message them anymore,” Metturson tells New Lines. “If I continue to write to them, they will end up in the camps, if they are not already there.” Uyghurs with ties abroad were some of the first to be targeted for arrests.

Metturson’s 34-year-old sister, Salamet, sits next to him sobbing loudly, wiping her eyes with a handful of tissues piling up beside her. While Metturson has not heard any news of his wife and children, he says he was able to confirm that at least 10 of his family members were in the camps, including another sister and his mother.

Metturson’s father died five and half months into a prison sentence in 2017. He learned that his body was returned to the family by the Chinese authorities, but under strict surveillance. Only immediate family members were permitted to attend the communal “janazah” funeral prayer traditionally performed by Muslims. They were accompanied by about 20 armed police officers as they carried him to his final resting place.

“They want to make the Uyghur extinct by killing the eldest and brainwashing the youngest,” Metturson says. “Then there will be no one left who can claim that the land of East Turkestan belongs to anyone but the Chinese.”

Metturson and Salamet are among scores of Uyghur families in Turkey who have decided to speak out, demanding answers on the whereabouts of their disappeared loved ones. “There’s nothing left to fear,” Metturson says, leaning up against the bright white walls of the mosque. “They have already taken most of our loved ones. So what more do we have to fear?”

Before Metturson fled in 2014, life in Xinjiang was already worsening. “The pressure was everywhere,” he says. “In East Turkestan I couldn’t have my friends or family visit my house for more than two hours. Three or four Uyghurs cannot speak together without the Chinese becoming suspicious.”

According to Omer Kanat, executive director of the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), these ethnic tensions have been simmering for many years, at least since the People’s Republic of China invaded the region in 1949 and overthrew the short-lived East Turkestan Republic, absorbing them into the modern Chinese state. However, the region has seen thousands of years of attempts by leaders, tribes and China’s imperial dynasties to control this resource-rich territory.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) introduced increasingly repressive policies in Xinjiang throughout the 1990s, along with enticing Han Chinese to migrate to Xinjiang in order to manipulate the region’s Uyghur majority demographic. In 2009, peaceful student protests in Urumqi mushroomed into deadly clashes between Uyghur and Han Chinese. The Chinese government blamed the unrest on Uyghurs, and life in Xinjiang began to change dramatically.

“Before 2009, we had police roadblocks when we traveled between cities or towns,” Metturson explains. “But after 2009 we had to cross roadblocks going from our house to a neighbor’s house.” Police and military raids became an almost daily occurrence for Uyghur families.

Salamet, who also fled the country in 2014 to Egypt and ended up in Turkey in 2017, says her home was raided almost daily in Xinjiang. “They were always raiding our home looking for my younger brother,” she says, with tears running down her face. “They targeted all the Uyghur youths. They would raid our home almost every night.”

“They would break into the cabinets and turn over the beds,” she recalls. “They would look through the closets to see if someone was hiding.” After she fled the country, she received news that their 24-year-old brother was sentenced to eight years in prison.

Salamet is an avid reader and would keep Uyghur history, literature and poetry books in the house. Like numerous other Uyghur families, she was forced to collect the books and bury them in a nearby cemetery to avoid being arrested.

As the CCP’s clampdown on Uyghurs increasingly became framed around anti-terrorism, restrictions also escalated on the practice of Islam in the region.

Throughout Uyghur history, “Islam became a central part of Uyghur life and traditions,” Kanat explains. “Islam played a very important role in preserving the Uyghur national identity. The Chinese government realized that if they don’t eliminate the religion of Islam, it will be very difficult to eliminate and assimilate the Uyghur people.”

Tens of thousands of religious figures and students were arrested and given long prison sentences. Uyghurs and other Muslims caught fasting during Ramadan, praying or possessing Qurans in their homes were rounded up and accused of religious extremism.

According to Kanat, to determine if Muslims were fasting, school and university administrators would offer lunch to students; if they refused to eat the food, they would be expelled. “In front of the gates at universities and schools, they placed hundreds of bottles of water during Ramadan,” Kanat explains. “Any student who entered the school would have to drink water to prove they were not fasting.”

Police patrolled the backstreets of Xinjiang in the early morning hours during Ramadan, checking if Muslims were taking “suhur,” a pre-dawn meal consumed before starting the day’s fast. “If someone had their light on before sunrise, that meant this family was fasting and their home would be raided,” Kanat tells me. “Hundreds of Uyghurs were arrested this way.”

After targeting the pious Uyghurs, the Chinese authorities moved on to the intellectuals or those with ties abroad, arresting scores of Uyghur writers, poets, historians, academics and businesspeople. In 2016, “China’s assimilation policies turned into an all-out war against the Uyghur people,” Kanat adds.

Hundreds – perhaps thousands – of police checkpoints have been erected throughout Xinjiang, and millions of cameras and state-of-the-art facial recognition technology track residents’ every move. Thousands have been arrested for making trips abroad, communicating with a relative overseas, using unauthorized apps like WhatsApp, paying for their children’s education abroad, wearing a hijab, having a long beard, or possessing religious or Uyghur language books.

By 2017, a vast network of mysterious facilities were built in the region’s desert, appearing to be massive internment camps. According to Amnesty International, the more than 1 million detainees believed to be held in these facilities are subjected to a “ceaseless indoctrination campaign,” which includes praising Chinese President Xi Jinping and renouncing Islam.

Detainees reportedly face “physical and psychological torture and other forms of ill-treatment,” including electrocution, waterboarding and sexual abuse. The camps are considered the largest mass internment of an ethnic-religious minority group since World War II.

The United States and other countries have accused China of genocide and crimes against humanity. But the Chinese government claims the camps are merely “vocational education and training centers” aimed at reducing religious “extremism” and poverty.

Since 1952, the Turkish government has offered asylum to Uyghurs fleeing Xinjiang after its takeover by Chinese communists. Turkey continues to provide temporary or permanent residency for Uyghurs in exile. Over the years, about 50,000 Uyghurs have fled Xinjiang to seek refuge in Turkey, mostly in Istanbul.

Uyghurs in Turkey were forced to watch — powerless and helpless — as the unthinkable unfolded back home. Many have not had contact with their relatives in Xinjiang for years. Others have received news through indirect sources that their loved ones have ended up in the internment camps or prisons. Hundreds of children in Istanbul have been left unaccompanied after their parents were detained in Xinjiang during trips home.

In 2019, Uyghur families began to organize themselves, staging dozens of protests outside the Chinese consulate in Istanbul and its embassy in Ankara. Uyghurs who choose to speak out do so at great personal risk. Several families in Turkey have reported receiving death threats from the consulate after speaking out in the media.

But Uyghur families are marching on. The protests have now grown from just a dozen participants to several hundred. A July 5 protest held outside the Chinese consulate marking the anniversary of the 2009 Urumqi unrest, which Uyghurs refer to as the “Urumqi massacre,” saw hundreds of Uyghurs — old and young — passionately waving the flag of the Uyghur independence movement, baby blue and emblazoned with a crescent moon and star.

The 2009 unrest was sparked in response to a mob of Han Chinese workers who beat Uyghur colleagues at a toy factory in the southeastern city of Shaoguan in Guangdong province. At least two Uyghur workers were killed and scores were injured.

The Chinese authorities opened fire on a protest staged by Uyghur students in Urumqi who were demonstrating against the incident, spurring violent riots throughout the city. According to the Chinese government, the Urumqi unrest was marked by violent attacks on Han Chinese residents in Xinjiang, with a total of 197 deaths, most of whom were Han Chinese. Almost 2,000 others were injured.

According to UHRP, thousands of Uyghurs disappeared from Urumqi in a weeklong campaign of mass arrests. Many Uyghurs claim this 2009 crackdown was the precursor to today’s mass internment of Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities in Xinjiang.

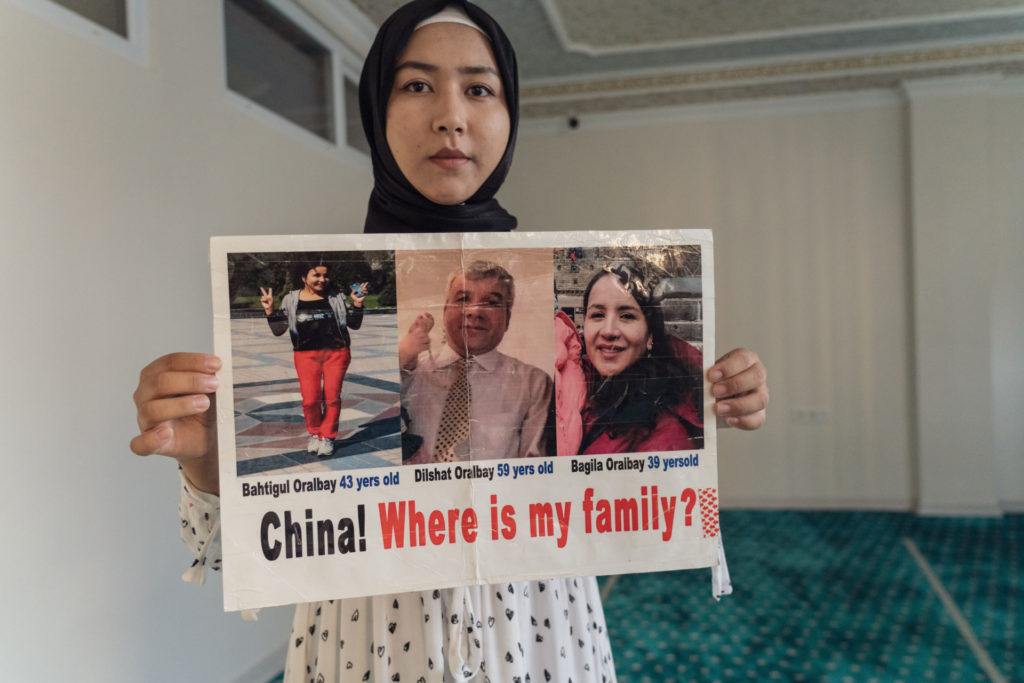

At the July 5 protest in Istanbul, many protesters held placards plastered with the faces of Uyghurs detained in China’s internment camps. Some broke into sobs as they sang “Qurtulush Yolida,” or “March of Salvation,” considered by many to be the Uyghur national anthem.

A child at the front of the protest shouted at the top of her lungs, her face turning red and veins protruding from her neck: “Turkestan belongs to us! And it will belong to us again!”

Memet Tohti Atawulla, 32, fled China in 2016 and is living alone in Istanbul. He rattles off the list of his family members he has heard are in the internment camps: his two younger brothers were arrested in 2017; his mother in 2018.

One month after his mother’s arrest, all contact he had with his family was severed. “I used to call them on their landline,” says Atawulla. “Since May 2018, it has been disconnected. I think the police took the landline from the home.” Atawulla immediately went to the media after he lost contact with his family, while also writing letter after letter to Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, pleading for help in locating his family. “But, still, there’s no response,” he says.

In May, thousands of pictures and documents from the Xinjiang internment camps, known as the “Xinjiang Police Files,” were leaked to the public. Atawulla says he felt “great pain” when he viewed the teary-eyed faces of the detainees, many of whom were children.

“I felt so sad when I saw these photos,” he says, furrowing his brows. “I know that my family is in the same situation as them. For years, I haven’t been able to think about anything else except this. I know they are going through so much pain. I just hope they are still alive.”

Metturson has been too afraid to look through all of the photos from the leak; his wife is from Kashgar, the Xinjiang prefecture where most of the files were leaked from. “I’m scared that one of them may show the face of one of my missing family members,” he says, tightening his jaw and closing his eyes. “I would never dare to look too closely at them.”

Protest placards displaying some of the thousands of pictures of faces obtained in the leak are stacked in a pile beside Metturson. He glances at them, then picks up the top placard by its wooden handle and flips it over.

He stares at it for a few seconds before extending his arm to present an image of a woman whose picture has become iconic for the suffering of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Her eyes, filled with tears, stare desperately into the camera.

“Look at this woman,” Metturson says, using his free hand to gesture to the poster. “She looks like she is praying that someone can save her. What could this woman possibly have done to deserve this? My mom is elderly, in her 70s, what crime could she have committed?”

Along with the thousands of leaked photos and documents, there are transcribed speeches by high-level Communist Party officials who encouraged camp administrators to shoot detainees who attempted to escape the camps. The Chinese government dismissed the leak as “lies and rumors.”

The leak also came at the outset of a visit to the region by the U.N.’s High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, whose long-awaited human rights assessment on the situation in Xinjiang was published on Aug. 31. In the report, she concluded that China was responsible for “serious human rights violations” and that the mass arbitrary detentions against Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities “may constitute international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity.”

After the leak, hundreds of Uyghurs in Turkey staged a consecutive five-day protest outside the Chinese embassy. One of these activists is Medine Nazimi, 39, who lost contact with her sister Mevlude Hilal in 2017.

Hilal, who has Turkish citizenship, was studying at Istanbul University but returned to Xinjiang around 2013 to take care of her ailing mother. Some months after losing contact with her sister, Nazimi received news that Hilal was sent to an internment camp and then allegedly sentenced to 10 years in prison on a charge of “separatism.” Hilal is married with a young daughter, who was just one year old when she was arrested.

“They arrested her for no other reason except for the fact she is Uyghur,” says Nazimi, who, for years, has also not had contact with any of her other relatives in Xinjiang. She assumes they are also in the camps.

“All of this is political,” Nazimi adds. “They call us terrorists so they can get rid of the Uyghurs, assimilate us and eliminate us so they can grab our land for their future development projects.”

In 2015, Erdogan declared he would always keep the country’s doors open for Uyghur refugees. In 2019, Turkey’s Foreign Ministry called the camps “a great embarrassment for humanity.”

Yet Erdogan’s attempts to boost Turkey’s economic ties with China have made Uyghurs in the country wary. He has accused the media of “exploiting” the Uyghur issue to undermine Beijing-Ankara relations and has since fallen silent on the issue.

In 2017, Beijing and Ankara signed an extradition treaty, which was ratified by China in 2020. This has struck fear into the tens of thousands of Uyghurs residing in Turkey who could potentially be sent back to China, where many would likely face the death penalty.

In recent years, the Turkish government has rejected Uyghur applications for asylum and long-term residency, while also allegedly deporting Uyghurs via third countries, such as Tajikistan, where it is easier for Beijing to secure their extradition. According to a CNN investigation, at least dozens of Uyghurs have been deported to China from Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia.

“The Turkish government needs to do something,” Nazimi says, as tears well up. “My sister is a Turkish citizen. This government should be doing everything they can to secure her release from the camps. But they are doing nothing.”

Mirzehmet Ilyasoglu, 41, has lived in Turkey since 2007 and has Turkish citizenship. His 38-year-old brother was arrested by police in Xinjiang in March 2017. The first time, however, he was forced into “short-term re-education” for two weeks before being released, Ilyasoglu says.

According to rights groups, all former detainees are kept under near-constant electronic and in-person surveillance for several months following their release from the camps, including invasive “homestays” by CCP cadres who monitor them and report “suspicious” behavior.

Uyghurs have described the transformation of their loved ones’ behavior after being released from the camps. Many become withdrawn and closed off — too fearful to describe what they endured. Ilyasoglu’s brother was no different.

“I was video chatting with my elder brother,” Ilyasoglu recounts. His younger brother, freshly released from his short-term stay in the internment camps, “was walking around the yard in the background. I asked him to come chat with me and he refused to speak with me — like he was really scared of something.”

Just a few weeks later, his brother, whose daughter and son were just one and four-years-old at the time, was arrested again. “Until now he has not returned home,” Ilyasoglu says. “I’m very worried about his well-being. Some people are coming out of the camps disabled. Others die shortly after their release.” Ilyasoglu has since received news that another brother has also been taken to the camps.

“China is not only targeting the living, they are also targeting our dead,” Ilyasoglu adds. According to several investigations, China has destroyed more than 100 Uyghur cemeteries in Xinjiang over the last few years.

“They are destroying even the memories of our ancestors — erasing their graves like they had never existed,” Ilyasoglu says. “We are weak. Uyghurs don’t have a military. We have no power. We are all feeling helpless to stop this genocide.”

“And the whole Muslim world has fallen silent on this injustice,” he adds, shaking his head in frustration. “They prefer their economic benefits and their relationship with China over the lives of their Muslim brothers and sisters. They are shaking hands with China while their Muslim brethren are being exterminated.”

China’s operations soon escalated until no Uyghurs were safe in Xinjiang.

Malike Mahmut, 24, thought her family in Xinjiang was secure. Mahmut, whose father is Kazakh and mother is Uyghur, came to Turkey in 2015 to attend school. She is now a student at Istanbul University studying computer science.

She digs into her tote bag and retrieves photos of her uncle and two aunts now held in the internment camps; she delicately lays the photos out in front of her. Mahmut’s uncle was a member of the CCP and worked as a writer for a government newspaper and a translator for various Chinese films, books and news articles.

Following his retirement, he moved to Kazakhstan to open up a factory that manufactures windows. Every year, he would travel back to Xinjiang to visit family. “But in 2017, he began getting calls from the police station in Urumqi requesting that he come and sign some documents and answer some questions,” Mahmut says in a soft voice.

“My grandmother was telling him not to come back because the situation was getting so bad,” she continues. “But my uncle thought he was safe because he worked for the CCP, and he is not a practicing Muslim. At that time, it was mostly religious people being targeted. He did not think he was in any danger.”

Upon his return to Xinjiang in 2017, the Chinese authorities confiscated his passport. A few months later, he was arrested in a raid on his house in the city of Kuytun. His two sisters, Mahmut’s aunts, were also arrested in the raid. Mahmut has not heard from them since.

“This has all been a shock for me,” Mahmut says, her voice cracking. “None of us thought that these policies would ever affect us. My family was always well-behaved and aligned ourselves with the Chinese government. We were always taught that whatever the Chinese do, that’s what we should do too. But even this did not save us.”