At the crossroads of Saudi Arabia’s bloody campaign in Yemen, a steady stream of arms from the United States, Iran’s uncertain shadow over the peninsula, and the al-Houthi rebels’ battle for political supremacy, lies a ship.

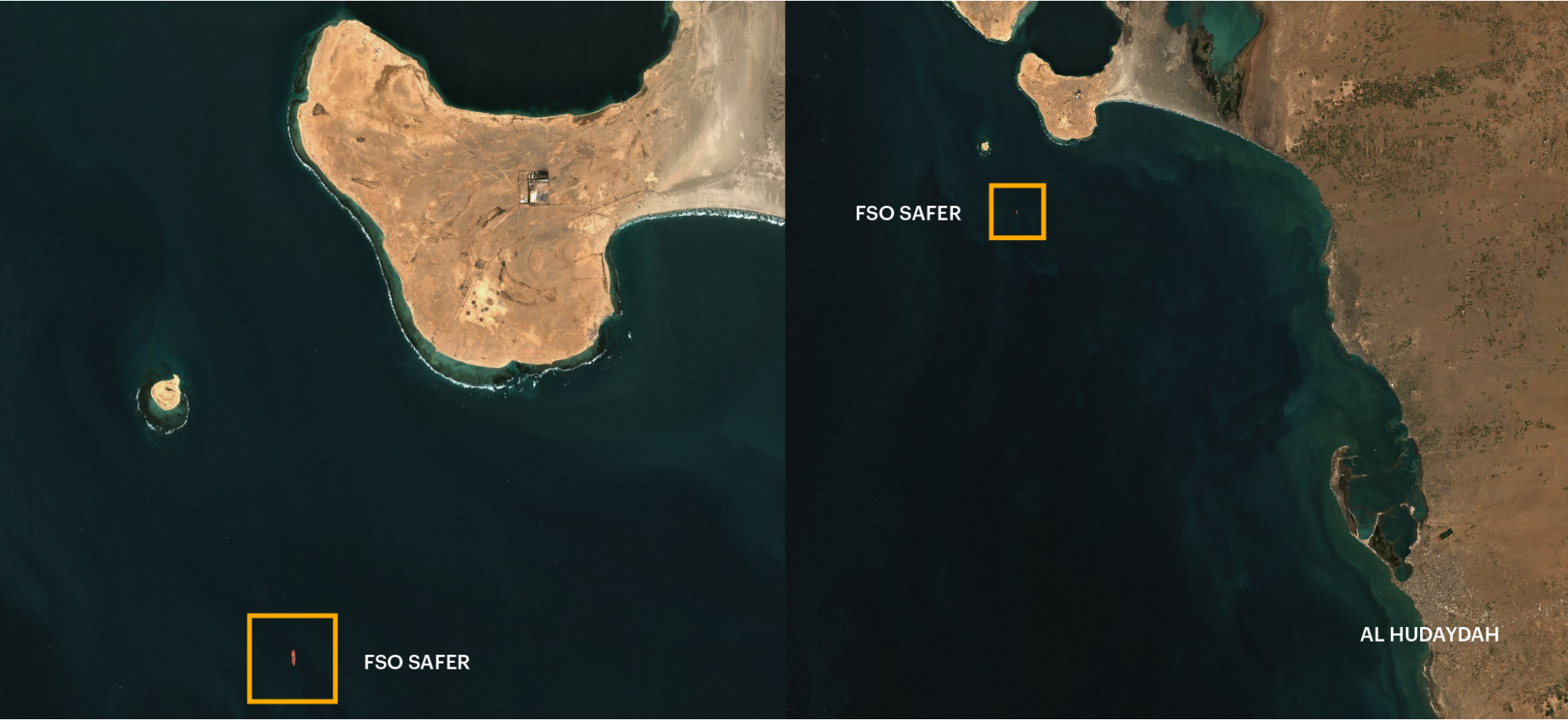

The vessel, moored 4 miles off the Ras Isa port in Yemen, was used as a storage terminal for crude oil until 2015, when it was abandoned after much of Yemen’s western coastline fell under the control of al-Houthi rebels. Neglected and without maintenance for over five years in the hot, saline waters of the Red Sea with over 1 million barrels of crude onboard, the “SAFER” — its English transliterated name — has decayed rapidly, threatening an oil spill four times the size of the Exxon Valdez disaster in 1989.

None of the countries bordering the Red Sea is more vulnerable to a SAFER spill than Yemen. A huge contamination of oil threatens to upend every layer of the war-torn country’s fragile socio-environmental system, from its mangrove swamps and bountiful fish stocks to its largest port in Al Hudaydah, where virtually all of the nation’s humanitarian aid arrives. But other countries would be affected, too. Predictive models indicate that in the event of a major oil spill, slicks could travel up the Saudi coast and into the center of the Red Sea, impacting Egypt’s marine tourism industry. Some experts have warned that the oil could travel as far as the Gulf of Aqaba, destroying the only coral reefs in the world predicted to survive beyond the middle of the 21st century.

Despite these risks, the challenging political climate in the region has led to years of inaction as the vessel slides further into disrepair. The SAFER crisis would only be the latest — and possibly the most egregious — example of the willingness of regional actors to put the environment and the people who rely on it in extreme danger to maintain a status quo that is favorable to their geopolitical interests.

Many will recall the spectacle of black smoke billowing out of the desert floor in 1991 when Saddam Hussein ordered his retreating troops to set Kuwait’s oil fields ablaze. Smoke from the fires choked the air and caused outbreaks of respiratory and skin disorders in Kuwait and elsewhere. During the same period, the dictator drained Iraq’s salt marshes in the south in an effort to punish the political dissidents who lived among them. Despite restoration efforts, the water levels have remained well below what they once were.

More recently, the failure of Lebanese officials to remove over 2,700 tons of highly explosive ammonium nitrate from a hangar in Beirut’s port led to the largest non-nuclear explosion in modern history. The blast killed over 200 people, injured over 6,000 more, and left behind thousands of tons of waste, including toxic chemicals. The public, particularly those tasked with cleaning up the mess, will suffer the brunt of the exposure and any resulting medical complications for years to come.

The SAFER dilemma bears striking similarity to the prelude of Beirut’s blast, with plenty of foresight and warnings from scientists and the public to act swiftly before the inevitable disaster. The oil onboard the vessel, like the ammonium nitrate in the hangar, has sat idle for over five years, capable at any moment of catching fire and igniting a massive explosion.

The world knows what that explosion looked like in Beirut. It may soon see it happening in Yemen.

The SAFER is an ultra-large crude carrier (ULCC) capable of storing up to 3 million barrels of oil. It was originally built for Exxon in Japan in 1976 for the purpose of transporting oil west through the Cape of Good Hope while the Suez Canal was closed. In 1988, the Yemeni government bought the vessel and converted it into a storage tanker for oil exports traveling through the Marib-Ras Isa pipeline to the Red Sea.

Before the SAFER’s abandonment in 2015, it was already 20 years past the average life expectancy for an oil storage tanker, according to Abdulghani Abdullah Gaghman, a Yemeni geologist and consultant. He added that the extremely hot and humid environment of Yemen’s coastline is hostile to any mechanical instrument and has quickened the vessel’s demise.

The age of the ship, coupled with its high maintenance and operating costs and its precarious location in the Red Sea led the Yemeni government in 2006 to begin planning the creation of oil storage tanks on land in the Ras Isa port. However, the project never made it past its foundational phase.

When Yemen’s war broke out in 2015, workers were told to abandon the SAFER. Since then, Gaghman said, “the fate of the ship has been at the mercy of God and the sea.”

The storage and transport of oil on the high seas is a risky business, where the potential for a spill is ever-present and where the impacts of that spill on human lives and the environment is assured but difficult to predict. An estimated 3.4 million barrels of commercial oil travel through the Red Sea every day. Historic precedents confirm that the sinking or severe malfunction of any one of the vessels carrying that oil would have dire consequences in both the short and long term.

When the Exxon Valdez ran aground on a reef off the coast of Alaska in 1989, it affected over 1,200 miles (2,000 kilometers) of coastline, of which 185 miles were either moderately or heavily oiled. Despite the millions of dollars poured into cleanup efforts, only about 10% of the oil was removed. More than 30 years later, many of the region’s wildlife populations have not yet recovered, and a major fishery remains closed.

Yemen’s coastal communities cannot afford even a fraction of such devastation. For decades, the fishing industry was one of the most productive sectors of Yemen’s fragile economy. Before the 2015 war, fish was the country’s second largest export. The sector provides job opportunities for more than half a million individuals who in turn support 1.7 million people, forming 18% of the coastal communities’ population.

Using data from Yemen’s Environmental Protection Agency and Central Bureau of Statistics, the Yemeni environmental organization Holm Akhdar (Green Dream) estimated that a massive oil spill near Ras Isa would destroy over 800,000 tons of fish stocks in Yemen’s waters and that the marine ecosystem could take over 25 years to recover. Other experts have warned of consequences beyond the mass death of marine life.

British risk-analysis company Riskaware predicted that a SAFER spill could force the closure of Yemen’s largest port at Al Hudaydah for five to six months, causing fuel prices to spike 200% and interrupting health, water, and sanitation services. In the event of a major fire on board the vessel, extreme air pollution could coat agricultural land with soot and ruin crop yields for over 3 million farmers.

Karine Kleinhaus, a marine science researcher at Stony Brook University in New York, worked with a team of researchers to model the dispersion of oil from a SAFER spill. The resulting maps indicate that a spill during the winter months could disperse oil far north and into the center of the Red Sea, where it would remain trapped indefinitely. The sea’s coral reefs are regarded as a critical global resource due to their unique ability to withstand abnormally high temperatures without bleaching.

The al-Houthi rebels that control access to the tanker have scoffed at the environmental concerns of marine scientists.

“The life of the shrimps is more precious than the life of a Yemeni citizen to the U.S. and its allies,” wrote top al-Houthi leader Mohammed Ali al-Houthi, apparently responding to warnings of environmental devastation from international experts.

The sentiment echoes a long-standing tension in crisis areas — that concerns of ecological degradation obscure the plight of ordinary people. Yet the two are obviously connected. Kleinhaus noted that the Red Sea’s reefs and marine life are critical to the subsistence fishermen of Yemen’s coastal cities.

“It’s natural for people to miss the connection between the fish and the humans,” she said. “But the fish are actually feeding the Yemeni people.”

In June 2020, there were reports of seawater leaking into the SAFER’s main engine room. The state-run company that owns the vessel sent a team of divers to find a quick fix to the seepage, but evidence of deep decay has contributed to the belief among many that a major disaster is imminent.

In a July briefing to the United Nations Security Council, U.N. Environment Programme executive director Inger Anderson described the precarious state of the vessel and the calamitous consequences of inaction. “This disaster is entirely preventable, if we act fast,” Anderson stated. “The U.N. possesses the capacity to intervene and resolve the problem.”

Six months later, however, the tanker remains moored in the sea with over 1 million barrels of crude onboard. Last week, al-Houthi leaders once again delayed a U.N. mission to inspect the vessel.

This latest move is likely their strategy to pressure the United States into revoking the group’s recent terror designation. For the past several years, however, the inaction has been due in large part to disagreement between the al-Houthi rebels and the Saudi-backed Yemeni government over who should collect the $80 million in revenue from the oil onboard the SAFER. While $80 million is only a fraction of what it would cost to clean up the oil from a major spill (a pittance to the Saudi government), it is a significant sum in war-battered Yemen, where many citizens have not received wages in over five years.

Not surprisingly, the al-Houthi rebels and the Saudi-backed government have prioritized a squabble about oil revenues over averting a major environmental and humanitarian crisis. Both factions have independently highlighted the devastating possibilities of a SAFER disaster — but only to preemptively blame the other for the fallout, should it occur.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of the SAFER situation is the logistical simplicity of its solution. The tanker could easily be dragged to shore, its oil offloaded and stored until a decision on what to do with it is reached. Alternatively, the oil could be transferred onto another tanker in better condition, or the al-Houthi rebels and the Saudi-backed government could come to an agreement on how to split the revenues. Either way, Yemen could be spared from a catastrophe it can’t afford, either financially, environmentally, or morally.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.