“If you’d have come here to tell me that my son is still alive, you would have made me the happiest mom in the world.”

Svetlana Antipova opens the gate to allow us into her yard in the village of Shyryajeve.

It is a pitch-black Saturday evening, a little over an hour’s drive outside Odessa, Ukraine. The stillness is interrupted only by dogs barking in the neighbors’ yards, alerted to the arrival of strangers.

Evgeny Antipov, Svetlana’s son, was a mercenary in the Wagner Group, Russia’s notorious private military company. Evgeny was killed somewhere near Homs, in central Syria, four years ago last June. A little over a month before he left, Evgeny had told his mother that he was going on an unspecified work trip for the next three months. “I won’t have a phone with me,” he told her. “When I come back, I will call you.”

His call never came.

Evgeny’s friends, rather, contacted Svetlana on the Russian-language social media platform VKontakte, telling her that her son was dead.

Evgeny is one of 4,184 Wagner mercenaries that the SBU, Ukraine’s security service, and a think tank started by a number of former top SBU generals have identified. The Ukrainian Center of Analytics and Security, or UCAS, as the think tank is known, shared its data with New Lines, Estonia’s Delfi.ee and the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter.

The trove of information offers arguably the most comprehensive anatomy of Russia’s dark army, built and paid for by the Kremlin-backed oligarch and catering magnate Yevgeny Prigozhin. Coyly referred to in the press as “Putin’s chef,” Prigozhin has been serially sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury Department for his role in Russia’s invasion and occupation of Ukraine, multiple instances of U.S. election interference, and, most recently, malign political and economic influence peddling in the Central African Republic (CAR).

Wagner’s mercenaries have been fighting on the side of the separatists in eastern Ukraine, propping up Bashar al-Assad’s dictatorship in Syria and backing the warlord Gen. Khalifa Haftar in Libya, as well as fighting anti-government rebels in the CAR. They have also been deployed to Sudan, initially in support of since-ousted dictator Omar al-Bashir, and Mozambique, where they mounted a disastrous and swiftly abandoned offensive against Islamist insurgents.

On Dec. 13, the European Union sanctioned the organization along with three companies and eight people connected to it. “The Wagner Group is responsible for serious human rights abuses in Ukraine, Syria, Libya, the Central African Republic (CAR), Sudan and Mozambique, which include torture and extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions and killings,” the European Council stated in its sanctions decision.

Wagner is closely intertwined with and subordinate to the Russian Ministry of Defense. The U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, a sanctions enforcement agency, has designated Wagner a “proxy force” of that ministry. Reporting has also shown it is very close to Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU. One of the group’s training facilities is located in the Russian region of Krasnodar, right next to a heavily guarded GRU Spetsnaz (special forces) military base.

Further links between the mercenaries and Russian military intelligence surfaced in the course of previous investigations conducted by the forensic news outlet Bellingcat. For instance, leaked airline data for flights between Moscow and Krasnodar showed that Dmitry Utkin, the commander of the Wagner Group, and senior GRU figures such as Col. Oleg Ivannikov traveled on jointly purchased tickets. A February 2015 call between Utkin and Ivannikov intercepted by the SBU shows the GRU’s dominant role in their relationship.

The EU has also confirmed that Utkin is “a former Russian military intelligence (GRU) officer” who is “personally responsible” for atrocities committed by his men, including “the torturing to death of a Syrian deserter by four members of the Wagner Group in June 2017 in the governorate of Homs, Syria. According to a former member of the Wagner Group, Utkin personally ordered the torturing to death of the deserter as well as the filming of the act.”

In a recent investigation into Ukraine’s abortive sting operation against Wagner, Bellingcat also found evidence that before being assigned as military adviser to CAR’s military chief of staff, a senior Wagner commander received training at the GRU’s Military-Diplomatic Academy in Moscow.

Most recently, the government of Mali has tried to recruit Wagner combatants in the fight against terrorist organizations affiliated with the Islamic State group and al Qaeda, prompting concern from the French-led peacekeeping coalition in the country.

The data on Wagner that New Lines and its partners have analyzed includes the call signs and special ID numbers of mercenaries as well as the name of their units and their rankings within them. UCAS also provided photographs mined from social media of each mercenary, typically featuring the subject brandishing weapons, Wagner memorabilia or medals for service. In many instances, the entry for each fighter consists of his nationality and even home address.

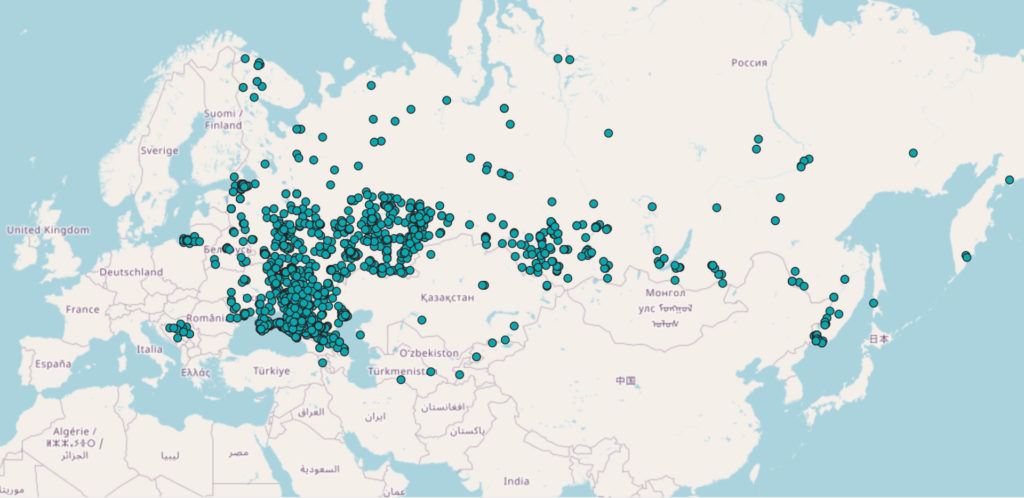

Among the 4,184 individuals in the database, fighters have come from 15 different countries, and some have multiple citizenships. The majority, 2,708, unsurprisingly hail from Russia, 222 from Ukraine, 17 from Belarus, 11 from Kazakhstan, nine from Moldova, eight from Serbia, four from Armenia, four from Uzbekistan, three from Bosnia and Herzegovina, two from Kyrgyzstan, two from Tajikistan, two from Syria, two from Turkmenistan and one from Georgia. (One fighter possesses triple citizenship: Lebanese, Ukrainian and Russian, although New Lines could not confirm his country of origin.) For the remainder in the dataset, 1,188, nationalities are unknown.

From fighters with established dates of birth, New Lines was able to determine that the average age of a Wagner mercenary is 40. The oldest, born in 1950, would be around 71 today (he died in 2017); the youngest, born in 1997, is 24. Thirty-three percent were born in the 1970s, 44% in the 1980s and 11% in the 1990s.

Of the 372 confirmed dead, 75 are known to have died from 2014 to 2016, 186 in 2017 and 86 in 2018. In the past two years, 23 fighters have died either on the battlefield or in other uncertain circumstances. The country with the largest number of fatalities is Syria, with 315 dying there; 35 died in eastern Ukraine and one near Kyiv; eight in Libya; and one in St. Petersburg.

Of the 372 dead, 315 perished in Syria, including 81 as a result of attacks by U.S.-backed forces.

“Wagner is like a layered pie,” says Vasyl Hrytsak, a former chief of Ukraine’s SBU. “It consists of both former and current military personnel but also of civilians eager to earn money and criminals who have been given an option to choose between prison or becoming a mercenary.”

Hrytsak and Gen. Ihor Guskov, his chief of staff at the counterintelligence agency, were among the SBU officials who established UCAS upon their retirement from government. They simply migrated the work they’d been doing for years to the private sector: identifying Wagner personnel, then using open-source intelligence capabilities to dig up as much information as possible on them. In close to half the cases, they hit a trove of data, thanks to the apparent fondness Prigozhin’s soldiers of fortune have for flaunting their affiliation online.

It was Guskov, in fact, who first defined the existence of the Wagner Group while he was at the SBU. He also identified their commander, the Ukrainian-born Utkin, whose fondness for Nazi iconography furnished the name for the mercenary corps, Richard Wagner being Adolf Hitler’s favorite composer.

“Wagner mercenaries earn good money by Russian standards, but there are very few Muscovites and people from St. Petersburg in it,” Guskov says. “A lot of people come from cities such as Orenburg, Astrakhan and Chelyabinsk. These are stagnating districts with low standards of living, a lack of perspective, alcoholism and drug addiction. People are looking for a way out of there and they are willing to pay with their life to do it.”

Russians with dim prospects aren’t the only ones who’ve joined Wagner. The data set also includes more than 220 Ukrainians and many Belarussians, Serbians, Moldovans as well as those with other nationalities.

New Lines set out on a trip to Ukraine to try to understand the path of becoming a mercenary. We knocked on the doors of mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters, and wives of men who have died fighting for Wagner in President Vladimir Putin’s dirty wars.

Often the families have been left without any knowledge of how their sons or husbands perished — or even where, exactly. Sometimes they blame themselves.

Evgeny grew up in a small house tucked between a tire shop and a gas station in a worn-out area of Odessa. His father, Yuri, helped him gain admission to a prominent arts school. Later, Evgeny did his conscription service as a police officer. But then his parents divorced, and Svetlana was impoverished. Occasionally she was also homeless.

Evgeny tried to help out with money. He also stole some of it, his father admits; these were funds Yuri had set aside for much-needed personal medical expenses. That’s when Yuri threw Evgeny out of the house. They had argued and fought before, but the theft crossed a line.

That event, eight years ago, was the last time father and son spoke. A few months later, in May 2014, Evgeny was embroiled in a tragic event at the Odessa Trade Unions House. Following running street battles between pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian protesters, which saw protesters killed by firearms on both sides, the pro-Russians were pushed back into the Trade Unions House. What happened next is still a subject of great controversy (both sides hurled Molotov cocktails at the building and from the roof). The building went up in flames and 42 people died from suffocation or injuries sustained in jumping from windows. An additional 174 were injured.

Evgeny, who had been on the side of the pro-Russian protesters, was arrested for his participation in the clashes. When he was released from jail pending trial, he fled to the war zone in eastern Ukraine. From that point forward, he had no way back home.

Later, when Yuri was cleaning out his son’s room, he found black ski masks known to be hidden there. He says he suspects that the FSB, Russia’s domestic security service, recruited Evgeny before the events at the Trade Unions House, although he admits he has no evidence to support that theory.

As Yuri sits behind a small, oilcloth-covered kitchen table, tears run down his cheek. Three green potted plants obscure the view through a large window to his right. “I don’t accept what he did,” he says. “But he was still my son and I love him.”

No one has told Yuri what happened in Syria when Evgeny was killed. That is all he wants to know. He has only seen a photograph of the gravesite in the Russian city of Rostov. There, the tombstone is carved with Evgeny’s image. On the top left corner there is a Wagner cross, awarded to mercenaries posthumously.

Yuri hasn’t been offered any compensation for the death of his only child — not by any of Prigozhin’s companies, much less by the Russian government. He calls it blood money and says he wouldn’t accept it in any case.

“I am for Ukraine, for my homeland, myself, and I have always been. I only want information on my son, how he ended up there,” Yuri says.

“No one can build anything on blood. Blood has never been a foundation for any construction. On the contrary, it turns into a swamp in which you drown. Why fight for strangers and kill for strangers?”

Svetlana received the news of her son’s death more than a month after it happened. She was working at the time in Poland. She says she doesn’t have any recollection of what happened next or how she traveled back to Odessa and from there to Rostov to visit the grave. In Rostov she was allowed just 24 hours to pay her respects.

“If you want to remain on good terms with us, don’t ask us any questions,” she says she was told. If she kept asking questions, she was told, she wouldn’t ever be able to cross the Russian border again to visit her son’s grave.

Evgeny was known to his Wagner comrades by his call sign Lanzheron, the name of a popular beach in Odessa. He died in Syria on June 9, 2017, a day on which at least four other Wagner mercenaries were killed there.

In the industrial city of Kharkiv, 400 miles northeast of Rostov, lives a family with a fate similar to that of the Antipovs. When we ring the bell on the top floor of a huge apartment building, Mark Bich’s sister, who can’t be more than 16 or 17 years old, answers. Mark died on the same day as Evgeny. Their tombstones in Rostov are just yards apart. At just 21 years old, Mark is the youngest fallen Wagner mercenary in our database.

His mother Natalya is a nurse. When she arrives home later that evening, she declines to meet us in person but agrees to talk over a Viber call. She says when her son died, they kept the news not only from his little sister but also from Mark’s grandparents and friends.

“For many people he might be a terrorist,” Natalya tells New Lines. “But to me, he is still my little son. My little son who was always so nice.”

Bich had moved to live in Rostov-on-Don in Russia with his wife and newborn baby, according to his VKontakte page. He wanted to earn money for his family. When he called Natalya and said he was going to work as a “peacekeeper” in Syria, she understood immediately what that really meant. “One needs to be completely nuts not to realize who is present there in Syria. Maybe I am from a different professional sphere, but I am also watching the news,” she says.

Mark didn’t have any military experience that his mother is aware of. Natalya tried to persuade him not to go, but he insisted. “I said I was against it, but he just said, ‘Mom, I love you.’ And that was it,” Natalya says.

Just a little over a month later Mark was killed. “He was just cannon fodder,” Natalya says.

The family doesn’t know what happened to Mark. Natalya says she has visited his grave, but she isn’t convinced that he’s buried there. “I suspect not,” she says.

In Ukraine, Mark Bich is still officially considered alive. Like all relatives of all other killed mercenaries whom we talked with, no one has received any formal notice of death. Getting a death certificate would mean going to court, but Natalya says she doesn’t have the strength to do so.

When asked what she would say to men considering becoming Wagner mercenaries right now, Natalya says that death is much closer than they think. “I don’t want them to die for someone else’s interest,” she says. “For your own interest, it would be heroism, but for someone else…”

There are a number of active recruitment ads looking for mercenaries on Russian job-seeking websites such as avito.ru. These vaguely worded classifieds offer roles to “security guards guarding and ensuring the security of the territory of objects abroad.”

Perks include three square meals a day, a recreation room and a free uniform. Even though the requirements stipulate that a license to carry a weapon isn’t mandatory, the ads characterize the assignments as armed. Previous experience in warzones is an advantage.

Salaries start at 150,000 rubles, roughly $2,000 a month, a competitive wage by Russian or Ukrainian standards. Additional evidence seen by New Lines suggests that people with solid military experience can easily earn twice that amount, a small fortune. But evidence also suggests that candidates are wary of being tricked; they might earn their promised pay in the first few months before their salaries either stop coming in or are less than before. These are the occupational hazards, apart from death, of joining a private military company in Russia.

“Money is an illusion for them,” an official from the Moldovan Security and Intelligence Service (SIS) tells New Lines. “They think they will sign up, go fight, earn money and support their families, but the reality differs. And when the reality sets in and they realize they are not being paid as promised, they start wanting to come home.”

A lieutenant colonel in SIS, the official agreed to talk only under the condition of anonymity because part of the official’s job in the anti-extremism and anti-terrorism unit of the service is to track down mercenaries of Moldovan descent.

The SIS official doesn’t lack for work. SIS has so far identified 114 mercenaries, of which 17 have been convicted for their participation in paramilitary organizations. A fraction of them is from Wagner; others have fought in the ranks of other private military organizations in the Donbas.

“These people are from an unstable social background,” the SIS official says. “They do not have stable jobs, stable incomes. The materialistic base is very important for these people.”

Anna Turuta, a psychologist from Moldova’s National Administration of Penitentiaries, has analyzed the profiles of convicted mercenaries. Barring certain exceptions, she has mapped patterns of demography and behavior.

All of them are men, most lacking more than a meager education; age ranges vary between 18 and 50, but most fighters are ages 25 to 30. They come from unstable home lives in which steady or reliable role models are often absent. They prefer isolation to company and tend not to trust other people. They find it hard to create or maintain friendships or start families.

“Another unifying element is a lack of empathy,” Turuta says. “They are unable to control their emotions, and they are cold in communicating. That is the main reason why these people are able to kill.”

Such a characterization holds true in the case of perhaps the most savage Wagner mercenary identified thus far by the Moldovan authorities and independent researchers.

Vladislav Apostol spent the first part of his childhood in the hilltop village of Ciutulești, a two-hour drive north of the capital Chișinau.

In 2017, Vladislav appeared in a video circulated on the internet showing five men, four of whom are beating Muhammad Taha Ismail al Abdullah, better known as Hamadi Bouta, a deserter from the Syrian army, with a sledgehammer, slicing off his hands and head with a spade and lighting his corpse on fire. (The fifth man, his face covered by a kaffiyeh, appears to have acted as the cameraman.)

Analysts soon geolocated the events depicted to a gas plant facility near Homs, Syria, where Wagner mercenaries were then stationed. This was the horrific incident cited by the EU in its sanctions announcement, along with the claim that Utkin ordered the torture and recording of it.

Vladislav and the others took turns wielding the sledgehammer.

Of the quintet that took part in the manufacture of the snuff film, all took selfies in front of the charred and dismembered corpse, some still wearing uniforms with Wagner insignia.

Vladislav died in March 2018 after being wounded by a U.S. airstrike during the battle of Khasham a month earlier. The clash, near Deir ez-Zor, took place when Wagner fighters and pro-Assad forces had attacked a position held by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces, shelling it with tanks and artillery. Because of the presence of U.S. special forces at the site, the U.S. Air Force and Marine Corps intervened with overwhelming firepower from rocket artillery, gunships, attack helicopters, strike fighters, even B-52 strategic bombers.

It is not yet clear exactly how many died among the Russian forces; the main reasons are not only the lack of independent access to the area of the clash but also the Russian government’s secrecy regarding the bodies and their repatriation. The dataset studied by New Lines contains the names of 77 other Wagner fighters killed on that date in Syria (another four would later die of injuries they sustained from that battle), the vast majority of them Russian or Ukrainian, in addition to at least one Kazakh, one Armenian and one Moldovan. According to sources in the region, not all the bodies of the dead have been returned or identified; some have never left Syria.

The house in Ciutulești where Vladislav grew up with his brother, mother and grandmother – which was eventually sold to a neighbor – has remained untouched for years. New Lines visited the residence in November. A window is nailed shut with planks; the yard is overgrown with weeds.

Villagers still remember the Apostols. A town official says that the brothers grew up without a father, whose name was even missing on Vladislav’s birth certificate. An activity leader working at the only school in Ciutulești says he barely attended.

“It was a difficult family,” says Valentina Bugan, the school activity leader. “There was no parental control over the kids and they had no interest in studying. They just didn’t show up.”

It was the ’90s and Ciutulești had just 3,000 residents, village clerk Maria Rusu explains. Even then, the village was emptying out. Residents left in search of work, some to other European countries, others to Russia. Among the latter were the Apostols.

Even though Vladislav grew up in Russia, attended a boarding school and did army service there, he maintained contact with his home village in Moldova. One of the people he was regularly in touch with was his neighbor, Vladislav Ungureanu.

The last time the two friends talked was in January 2018, just a month before Vladislav was fatally wounded in the battle of Khasham. His call sign in Wagner was “Volk” (“Wolf” in Russian), probably because he had a tattoo of one howling on the back of his neck.

“His contract [with Wagner] was supposed to end in May,” Ungureanu says. “He told me he was ready to come home, buy a house and Hummer. I realized that if he wants all that, he has the money as well.”

Ungureanu was waiting for Vladislav to call again on Feb. 10 to congratulate his friend’s wife on her birthday. “We were waiting. We thought the phone was going to ring, but it never did.”

Vladislav may have grown up without the presence of a male role model, but it was different for the Butnarciuc brothers on the opposite side of Moldova, in the village of Cotihana. Their father, Gheorghe, was always there — and that was the problem.

Two former neighbors of the Butnarciuks and a former teacher spoke to New Lines about the family’s history of violence. Gheorghe horribly beat his wife, Tina, often in front of the sons, Alexandru and Victor. Even at a time when domestic abuse was so pervasive in Cotihana as to almost qualify as a social norm, Gheorghe’s rages were extraordinarily savage.

“I suffered a lot because of this family,” Alexandru and Victor’s former teacher says. “I was saying things when [Gheorghe] did something wrong, but he was so brutal. I was really afraid of such people.”

According to the teacher, Alexandru and Victor began skipping school and refusing to do homework. When the teacher intervened with Gheorghe and Tina, nothing changed.

Soon after graduating from the eight-classroom local school in Cotihana, Alexandru and Victor left the village and were rarely seen or heard from again. Neighbors say Victor, the younger brother, ended up in prison in Greece, and Alexandru shared a similar fate in Russia. New Lines could not independently confirm whether this was true.

The family’s house is the first one next to the village school, which now lies in ruins; a new school has been established elsewhere in the village. The family’s home is intact but abandoned. The last time Alexandru visited was in 2016, for Gheorghe’s funeral.

He told his neighbors at the time that he was working in construction in the Russian city of Tomsk. In reality Alexandru was enlisted with Wagner. His current whereabouts is unknown.

Victor is not known to have been associated with Prigozhin’s operation (his name does not appear in the data set New Lines obtained), but he did fight as a mercenary on behalf of pro-Russian separatists in the Donbas. He was killed in September 2021, just as this investigation was getting underway.

The town of Slavyansk in eastern Ukraine is just a few miles from the active front line between the Kyiv-controlled part of the country and the Russian-controlled enclaves of the Donbas. It was among the first population centers seized by pro-Russian forces, including GRU operatives, in 2014. After fierce fighting, Ukrainian government forces regained control of Slavyansk.

Aleksander Motinga, a Ukrainian citizen, was one of those who left to fight on the Russian side and then became a mercenary in Wagner. His whereabouts is unknown. His brother Oleg lives alone in their parents’ house. Oleg doesn’t know how Aleksander was recruited.

“He called mother and said that he would go to the taiga to work in the forest,” Oleg tells New Lines. “He said he would be gone for two years and that he would not have a phone.”

The house in Slavyansk is small and shabby, with a vegetable plot outside canopied by corrugated tin. Inside, brick wallpaper is overpainted with hanging vines on one wall in the kitchen, opposite another wall covered in white tile. A teapot whistles on a grimy gas stove as Oleg flips through pictures from his and Aleksander’s childhood, of happy-looking holidays on a sailboat by the Sea of Azov, off Ukraine’s southeastern coast. Such family idylls stand in sharp contrast to the selfies Aleksander took in Syria and the Donbas, repeatedly posing with weapons.

According to the Wagner database, Aleksander was killed in Syria in June 2017, under unknown circumstances.

“Mom and Dad both died shortly after the news, from grief,” Oleg says. “They could not handle it.”

He’s not convinced that his brother is dead. “I know my parents are on the other side because I buried them myself. But how do I know that he is dead? I have no death certificate or anything. One day, maybe, he will come walking here.”

The lieutenant colonel in Moldova’s SIS tells New Lines there are generally three motives for people to sign up with private military companies such as Wagner. “First and foremost is the financial remuneration,” the officer says. “For some recruits, it is the basic element in the recruitment process.”

Second is kompromat, compromising information in their background such as a criminal past, for which they’ve eluded justice in their native countries.

“The third base is the ideological one that comes with the use of pseudo-patriotic feelings,” the officer says. “This includes a wide range of elements: social status, lack of education or geographical affiliation of people that makes it difficult for them to understand the current situation in the world.”

“They look for adventure at first but end up in big trouble. When they return, their mental health is affected because the experience they got was not so rosy.”

Although the former Ukrainian intelligence officers Hrytsak and Guskov believe that Wagner is already long gone from their country, they continue to map the mercenaries’ activities globally and build on their database.

The SBU has been happy to share its information with European counterparts, but, according to Hrytsak, the offers are often met by inexperience and naiveté on the part of the Europeans.

“We see a lot of pro-Russian ethnic, linguistic, cultural or sports structures popping up in countries such as Italy or Germany,” Hrytsak says. “Russia can take advantage of that to acquire visas [for those they’d like to recruit]. The European special services don’t pay nearly enough attention to this.”

Hrytsak adds that, technically speaking, there is no such thing as the Wagner Group because the entire enterprise is run by the Russian state. “Wagner is in fact Russian military intelligence,” he says.

“If they need to recruit 100 people tomorrow to do something illegal in Europe, these people will fly in dressed in civilian clothes in groups of two to five men. They will assemble, put on uniforms and take up arms. One small group can very quickly destabilize the situation in any country. That is the real danger of Wagner.”

– With additional reporting by Christo Grozev, Riin Aljas and Ruslan Trad