Ain Zara is a suburb of Tripoli, six miles to the south of the city-center and blue ripples of the Mediterranean that the Libyan capital surveys. The clusters of pock-marked, two-story, gray-and-yellow residential buildings, the TV tower, the Omar bin Al-Khattab Mosque and the expanses of dried grassy fields in between mark the limit of the Russian soldiers advance in April 2020. They were supporting the Libyan Gen. Khalifa Haftar’s attempt to overthrow the country’s disputed but U.N.-recognized government, the Government of National Accord (GNA).

“You’d better walk directly behind me,” says the 21-year-old mortar operator Haitham Waifalli, picking his way along a narrow path in the district that was his home for nine weeks when he was defending Tripoli. He’s concerned about unexploded ordnance and mines.

Haitham lifts his bulky, camouflaged body through a hole smashed in the wall of a house by a shell. A courtyard of rubble leads to a dusty kitchen, strangely untouched and domestic, if not for the empty green tin standing by the sink like a bottle of dish soap. “УЗРГМ Ф-1. 10шт” (“UZRGM F-1. 10sht”) read the typed Cyrillic letters. A can for 10 antipersonnel grenade fuses.

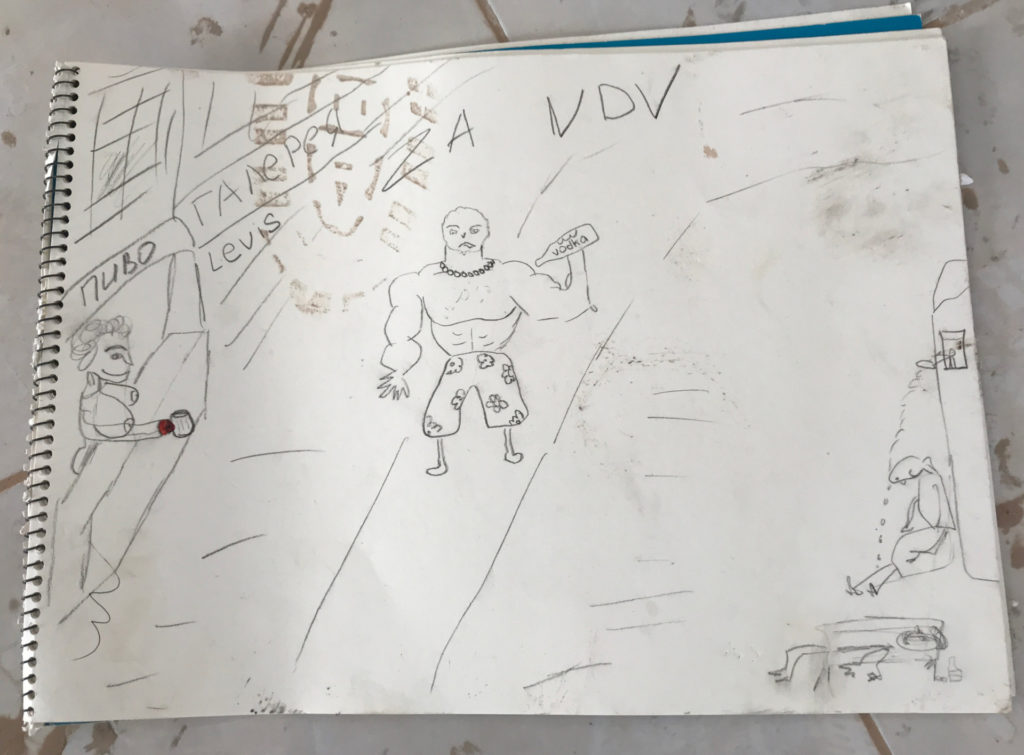

A pair of khaki military boots lie in a heap of debris, one of the soles unstuck — you wonder whether the feet that once wore them can still move — and an A3-size sketch pad gathers dust on the concrete floor. Inside, a bizarre pencil-drawing of a kind of post-apocalyptic fantasy world of a 13-year-old boy — a bare-chested barmaid offering a tankard under a sign saying “Beer” in Russian, two figures collapsed opposite, and center stage an orc-like muscleman in Hawaiian shorts and brash necklace, brandishing a bottle marked “vodka” (in English, for some reason). Above him, the words “Za VDV!” (“For the Airborne!”) — the standard slogan used to glorify Russian paratroopers and justify their doing whatever they like.

Haitham strides up the sweeping staircase, wooden balustrades missing, another gaping hole above him, this one through the roof. Tank shell, he says. He enters a room lined with three dozen green sandbags, wedged along the length of two walls. “Welcome to the kingdom of the Russian sniper,” he announces. “He had a clear shot from here. He could see everything.” As you peer through the two holes in this room’s walls — 15 inches or so in diameter, deliberately and strategically hewn — your eyes involuntarily become those of the mystery sniper who was once master here and who enjoyed the power to grant life or death to anything that moved in the 440-yard expanse now before you.

Nader Ibrahim, my colleague from BBC News Arabic with whom I’m making a documentary about Russian soldiers of fortune fighting in Libya, asks Haitham what he thinks of the people who fought from this house.

“Mercenaries,” he replies, with emotion. “They only care about making money. This is what they do. It’s their job. They kill people. They commit crimes for money. They’re a criminal organization.”

From September 2019, photographs and reports had begun to emerge of Russian mercenaries in Tripoli. They were identified as units from the so-called Wagner Group, a secretive and highly controversial organization of mercenaries that fought first in Ukraine, then in Syria, and later in Sudan, Mozambique, the Central African Republic and Libya.

Reportedly financed by the Russian catering magnate Yevgeny Prigozhin, who has been sanctioned and indicted by the United States for his election interference efforts, the Wagner Group has been accused of acting as President Vladimir Putin’s shadowy expeditionary force, even though mercenaries are technically illegal in Russia. The group has also been linked to the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence service, from whose ranks its ostensible head, Dmitry Utkin, and other rank-and-file members hail. And yet, as has often been the case with Wagner, beyond such reports and speculation over Wagner personnel’s involvement in the fighting, little detailed evidence had emerged.

But this spring we obtained a small white Samsung tablet with a cracked screen, protected by a battered brown leather case. GNA fighters said they had recovered it from positions held by Russian fighters in Ain Zara, the area where Haitham had fought. We put it through extensive tests to ensure it didn’t contain some kind of tracking device or malware; we examined it minutely, searching for clues to its users and making sure it was the genuine article. It was.

The tablet’s primary purpose seems to have been tactical, and it provides a fascinating and detailed window into the modus operandi and function of the unit Haitham faced.

Judging from the videos stored, the Samsung was used to operate a drone — or at least to examine the footage shot by one. Viewing the clips held on the device, you once again vicariously experience the Russian fighters’ perspective as you carefully look for Libyan fighters — but also witness firsthand the impact of the fighting on ordinary people’s lives. As the drone soars over whole districts, not a single human is visible. An entire population of civilians has fled their homes, leaving desolate empty streets and homes behind them. And just as well: The drone is hunting, searching for life as it flies over houses, broken walls and abandoned vehicles. Video released on social media connected to Wagner, and the testimony of GNA soldiers, demonstrate the firepower and effectiveness of the Russians in the environment they were fighting in: Howitzers, precision-guided mortars and well-trained snipers represented unprecedented challenges to GNA fighting units that were as often people’s militia as they were professional soldiers.

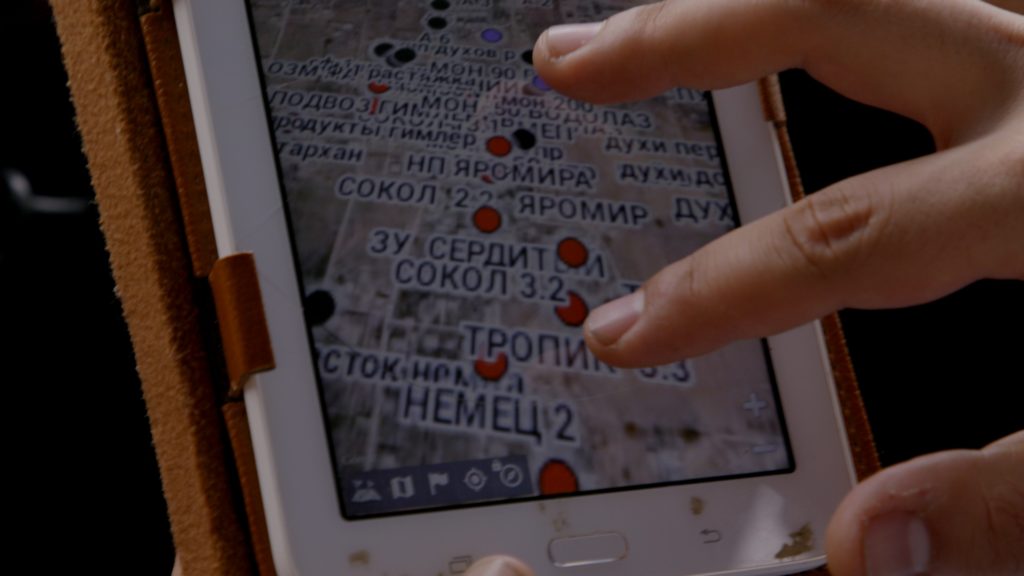

The tablet’s main interface is a map with dozens of marks placed in the Ain Zara area: red marks for Russian positions, yellow for their allies, blue for GNA forces and black for positions of mines. The fighting was evidently intense, positions of the opposing sides very close and intelligence from the drone exact. As Haitham identified his own position on the Russian map, he was visibly struck by the precision at the disposal of his adversaries. But as you delve into the content of the tablet, you find far more than day-to-day tactical information and frontline positions. You find yourself slipping further into the skin of the Russian fighter in Libya’s civil war, stealing glimpses of a life that, for the most part, has been represented by cliché — be it vilification or glorification — and guesswork.

Some of the marks read like a shorthand diary of incidents associated with points on the map. “VOICES SHOUTS ALLAH AKBAR,” for example. Or “TURKS BMP” — a Turkish armored vehicle. Or “Enemy incoming nighttime” — presumably referring to a shell or mortar landing. Or “Two thermal targets.” “Mosque.” “Rest base.” Or “SHOUTING SWEARING IN RUSSIAN.”

Libyans are represented in two distinct categories. The Russians’ allies are identified as “sadyk,” a Russian version of the Arabic word for friend — in this case referring to allies in Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA). The same term is used by Wagner to describe regime forces in Syria, their allies for six years already. The enemy, on the other hand, is described as “dukh,” the Russian word for spirit, or ghost, evocatively describing the invisible enemy Soviet soldiers were fighting in Afghanistan when the term was coined in the 1980s — but deriving from the word “dushman,” meaning “enemy” in Pashto and Dari. Dukh was also the word used to describe Chechen fighters in the wars of the 1990s and 2000s, as well as Syrians and others the Russians fought in Syria (including the Islamic State group). In Libya it meant the GNA, and people like Haitham. On the map we found marks like “DUKH MACHINE GUN” (“ПУЛЕМЕТ ДУХОВ”), for an enemy position, or “zu 23 sadyki” (“зу 23 садыки”) — an LNA anti-aircraft mount, “Zenitnaya ustanovka 23” (“Зенитная установка 23”), used in Tripoli and elsewhere for surface targets.

Positions of the dukh and the sadyk appear prominently on the tablet — and doubtless in the minds of the mercenaries themselves. But judging from our conversations with GNA soldiers, it appears that the Russian units in Libya fought as discrete units apart from their allies. Translators and guides were on hand to help communicate with the sadyks, or indeed with surrendering dukhs. Nevertheless, the Wagner fighters functioned independently and largely alone. Judging from descriptions of Wagner activity in Syria, the same was true there: Relatively small groups of Russian soldiers would be moved to certain locations on a front line to bolster defense and launch counterattacks. Or they would be instructed to advance and gain control of territory as part of a larger offensive and would act entirely alone for significant stretches of time, such as was seen in Palmyra. Or units of just a handful of men would be sent to operate behind enemy lines to gather intelligence or complete specific military tasks.

In Libya, according to the GNA commander of joint operations, Gen. Osama al-Juwaili, the Wagner forces came to assume ever more significant and active roles in the offensive. Initially, they managed artillery and functioned as snipers and were later deployed as spearheads in attacks on the front line. By spring 2020, when Wagner units were fighting in Ain Zara, they were already controlling whole spaces in their own right — as the tablet’s map seems to indicate.

The cracked Samsung also offers a fascinating window into the world and identities of some of the mercenaries fighting in Ain Zara. There are no social media profiles that we were able to trace on the tablet, but there was a library — and an extensive one at that.

The majority of the Samsung owner’s reading is, predictably, military literature. You have books on artillery fire correction, knife combat, weapons, tactics for fighting in urban spaces, nighttime combat, lessons of survival in wintertime, the use of unmanned aircraft, types of mortar and their use, and kinds of ambush. Other useful ones include “The Psychology of Interrogating Prisoners of War,” “How to Protect Weaponry from Corrosion,” and “The Art of Invasion.” A grand total of 11 titles are dedicated to mines and explosive devices — an interest underlined in the tablet by a large collection of illustrations and diagrams of explosives and their deployment, as well as photographs of improvised explosive devices being made in what looks like someone’s kitchen, and a video of a brick hut being blown up.

One of the legacies of Wagner fighters in Libya is the high prevalence of unexploded and unmarked mines in domestic settings in areas vacated by the group, as demonstrated by videos taken by GNA forces as they occupied these same areas and by the recording of numerous injuries and deaths of civilians. Leaving mines unmarked is a war crime, and the sheer number of black marks denoting mines on the tablet’s map suggests strongly that the group operating in Ain Zara may have contributed to this crime.

Other titles cover military history — from “Roman Legions on the Lower Danube” to the 1812 Napoleonic invasion of Russia and World War II. Particular attention is paid — not surprisingly — to recent Russian military experience, with books such as “The Chechen War. Work on Mistakes.” U.S. and NATO weaponry and tactical aviation are also covered. Then there’s the downtime reading. Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Mikhail Lermontov and even Joseph Brodsky are there; so, too, is J.R.R. Tolkien. And the entire series of “The Game of Thrones” and Dmitry Glukhovsky’s Metro books, which tell the story of survivors of global nuclear holocaust in the Moscow metro, are found on the device.

But the Samsung owner is not just interested in cerebral distraction. His library also offers a book on cooking, six titles on winemaking and a history of drugs from 1500 to 2000. And, in the psychology section, “Women: A Textbook for Men,” which on Goodreads promises that “after a man reads this book, the woman will no longer be incomprehensible to him”; and Tristan Taormino’s “The Ultimate Guide to Kink,” described on Amazon as “a bold and sexy collection of essays that delve into complex questions about desire, power, and pleasure.”

And then there’s politics and ideology represented by just two titles: Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” and Henry Ford’s “The International Jew.”

Who are the Wagner soldiers?

On the tablet there are 17 positions marked by red dots, all identified by what are apparently code names for the soldiers themselves. Some are Russian words: Sokol (Kestrel in Russian); Selenga (a river in Buryatia, in the Russian Far East); Gribnik (Mushroom-picker); Vodolaz (Diver); Metla (Broom); Serdityi (Angry); Veresk (Heather). Others are names, often old Russian ones, as though harking back to some kind of mythical ancient Rus, lost in the mists of time: Erofei, Yaromir, Yarmuk — as well as Masyanyan (diminutive from Maxim), Sparta and others. And a cluster of code names that echo the Hitler and Ford titles in the library: Nemets (German), Ariets (Aryan) and Gimler (a misspelled Himmler).

Since the first appearance of irregular Russian forces in Ukraine in 2014, fighters have used code names — or, as they are called in Russian, “call-signs” (pozyvnye/позывные). Ukrainian activists following the paths of these soldiers have identified many on their website Myrotvorets, or Peacemaker, providing social media pages, ages, home addresses, phone numbers and much more. The site is considered a reliable source of information among those studying and researching Wagner. However, it can be tricky to put real names to the soldiers because more than one might use the same code name at various times and some soldiers change their code names either when they move from one war to another or — in the case of some senior fighters — when their identities have become exposed.

Nevertheless, from the list of 17 code names marked on the map, we were able to identify two men whose noms de guerre appear to be unique and whose names are on unpublished lists of soldiers believed to have fought in Libya that were shared with us. Selenga is — according to Myrotvorets — 28-year-old Dmitry Vorontsov, from a small village in Buryatia close to the Selenga River. It’s an area of Russia with few work prospects and a high unemployment rate of nearly 11%. His Wagner number — 1868 — is sufficiently low, indicating he was probably one of the earliest members of the group. Our colleague, Ilya Barabanov at BBC News Russian, who has followed the group carefully and maintains good contacts among fighters and some of their families, considers that those with numbers up to 3,000 fought in Ukraine. That would mean that Vorontsov most likely joined Wagner soon after completing his national service when he was in his early 20s, in 2014 or 2015, at the moment that fighting in eastern Ukraine, or the Donbas, was raging. And ever since then, Vorontsov, aka Selenga, has apparently fought as a mercenary — his entire working life.

The second man identified — Metla — is 37-year-old Fedor Metelkin. It turns out that his code name doesn’t refer to a broom, but rather it appears to be a shortened version of his surname. According to information we gathered, this man fought in Chechnya in the Russian military before joining Wagner and fighting in Ukraine. His number is 1913, and according to the Myrotvorets site, he also served with Wagner in Syria and Sudan. That would suggest that Metelkin, too, may have spent most of his working life fighting in armed conflicts.

Metelkin comes from the predominantly Muslim republic of Kabardino-Balkaria, in the Russian North Caucasus. The wars in nearby Chechnya didn’t leave the place unscathed — an armed military Islamist operation attempted to seize the regional capital, Nalchik, in 2005 — and corruption, unemployment and interethnic tension are common across the region. But Metla doesn’t seem to be Muslim. Metelkin’s name suggests he is an ethnic Russian — and as a young man growing up in the Caucasus in the shadow of two Chechen wars, he is likely to have encountered his fair share of anti-Russian sentiment. We don’t know how important this may have been in Metelkin’s evolution, but a social media profile on the Russian VK network suggests he is another example of Wagner personnel with an interest in far-right ideology.

According to Myrotvorets, a profile under the name of “Anton Kulikov” belongs to Metelkin. As proof, the site provides a screenshot of the same social media account under Metelkin’s name, with a photograph of a German World War II soldier. The “Anton Kulikov” version is headed by the German phrase “Meine Ehre heißt Treue,” or “My Honor is called Loyalty,” a motto of the SS. Scrolling down, the profile reveals an interest in Vikings and Valhalla, metal and Celtic rock bands. One retweeted message reads, “These days it’s fashionable to watch what you eat and your appearance. I look forward to the day when it’s fashionable to watch your tongue and your actions.” This quote is accompanied by a picture of a large man with an axe standing in a forest. His T-shirt has a “kolovrat” wheel — a folkloric, so-called neopagan symbol associated with the far right today in Russia and elsewhere, known as the Black Sun in Germany and famously commissioned by the SS head Heinrich Himmler as a mosaic in Wewelsburg Castle in Germany.

The same symbol is also a favorite of one of Vorontsov’s social media friends, Mikhail Kashirsky, who, according to Myrotvorets, was a Wagner fighter and was killed in Syria in 2017. In his social media pictures, the shaven-headed and muscular Kashirsky stands proudly, baring his chest with a large Black Sun tattoo. In another photo he shows the same design on what appears to be a birthday cake, as he smiles to the camera in his camouflage, sleeveless T-shirt. We approached Metelkin for comment and received the reply that he is not a Wagner mercenary. We approached Vorontsov but received no reply.

Since its inception, there’s been much speculation about the Wagner Group’s connections with the neo-Nazi movement in Russia. The name itself is thought to derive from the code name of the military commander of the group, Utkin. This former lieutenant colonel of the GRU special forces is originally from Siberia and served until 2013 (including tours of duty in Chechnya and Dagestan) — after which he traveled to Syria to fight with the so-called Slavonic Corps paramilitary unit, a forerunner of Wagner. Trips to Crimea and eastern Ukraine followed in 2014, where Wagner was first seen, fighting on the side of Russian separatists against Ukrainian forces. Rumors have circulated that Utkin sports some kind of Nazi tattoo, and in 2020, a photo emerged of a man very like him whose chest and neck are adorned by a Nazi eagle and SS collar tab tattoos.

One Wagner vet we spoke to in Russia confirmed to us that the core of the organization is made up of people “with these radical views and hang-ups” and described them as “extremists,” many of whom have tattoos of pagan runes. He added that the symbols were part of many mercenaries’ self-identification with Viking culture — a popular vein in white supremacist ideology in Europe that harks back to an imagined “pure” and totally white past, as did Nazi thought in the 1930s.

The Libyan campaign also left unmistakable traces of this bizarre Third Reich-Valhalla marriage. Photographs have emerged on social media of Wagner soldiers — some dressed in German World War II uniforms — supposedly reenacting scenes from Gen. Erwin Rommel’s campaign against British forces in Libya in 1942. The charred walls of the burnt Niffati Mosque in Ain Zara — reportedly destroyed by Russian soldiers — bear “White Power,” Islamophobic and racist graffiti, in Russian, as well as a thunderbolt-like rune that matches other neopagan symbols found on the walls of houses used as bases by Wagner.

The neopagan strand in Russia dates to émigré thinkers who, following the 1917 revolution, argued that Slavs are a major branch in the “Aryan” family with roots in pre-Christian culture. In the postmodern, post-Soviet era, it became popular among nationalists with a new age bent, seeking a kind of lost, true path. In the war in Ukraine, it surfaced among volunteers and mercenaries fighting on both sides.

Yet for Wagner fighters we spoke to — not adherents to far right organizations — the slogans, rhetoric and symbols are viewed largely as performative posturing. One fighter explained: “There’s nothing serious in it. At least that’s the impression I got. It’s a game. Even the people who preach nationalist ideas don’t have any real understanding of what they’re talking about.” Asked whether Wagner fighters travel to foreign countries in order to commit violence and harm people because of Islamophobic or white supremacist prejudice, the answer was a categorical no.

And yet the bizarre preoccupation with these symbols among personnel, and indeed the sloppy error of losing a tablet with considerable, unencrypted operational information, tells us something else. Contrary to some representation in the Western media, Wagner is manifestly not an elite GRU unit made up of soldiers of the highest professional skills, discipline and capability. It is a force that very much reflects the society and population from which its members come, and one in which political and moral views may be far more nuanced than might be expected.

When asked to describe Wagner, one vet told us that the organization’s purpose was to advance the country’s interests beyond its borders, by the use of military force. When asked who joins Wagner, he listed the following categories: those who consider themselves soldiers of fortune and cannot imagine themselves in another life, those for whom there is no alternative way to earn a living, and “romantics” who seek a shot of adrenaline and want to serve their country.

Recruits to Wagner seem to come predominantly from the country’s less prosperous provinces — including Muslim areas, although this is a minority — while others are from big cities such as Moscow and St. Petersburg. When Wagner fighters traveled to Libya to fight at the end of 2019, the average monthly wage in many parts of provincial Russia was around 30,000 rubles ($500). Joining Wagner meant earning 180,000 rubles ($2,900), or for those in active combat, 240,000 rubles ($3,900). Tours of duty vary but may typically last three months.

Vets have told us that the organization lacks experienced soldiers, and the higher rates of pay for combat missions can prove tempting for soldiers who have returned to civilian life but whose ability to earn good money is limited. We heard of a soldier with experience of combat in the Russian army who was tempted from his job as a teacher in a rural school because of poor pay. He died in combat in Syria.

Wagner forces appear to be divided into seven so-called Storm Units, within which personnel and commanders are subject to change. All soldiers act under their code names and choose one when they join, though these can change. According to vets we spoke to, individuals’ real identities may remain a secret. If a soldier doesn’t know the real name of someone senior to him, he is expected not to ask. All will have completed their military service, which is now 12 months, in Russia. Some will have continued in the armed or security forces. Others will have served in the police or prison service. Submariners need not apply.

It is thought that a large proportion of Wagner fighters began their careers as mercenaries in eastern Ukraine or the Donbas. Others fought there as volunteers, came into contact with Wagner and never looked back. For some, the war seems to have been a life-changing, life-affirming and justified experience — to judge from discussion on Reverse Side of the Medal (RSOTM), a telegram channel and community that implicitly projects itself as a mouthpiece for Wagner and the like-minded. For others, traveling to the Donbas — where losses among the pro-Russian side are estimated at around 6,000 and where relations between militia groups ended in feuds and assassinations — was an experience that expelled any idea of the “romance” of war. From then on, one vet told us, the only reason to go and fight somewhere was money.

Many volunteers hardly launched into their lives as soldiers of fortune out of a love for Putin or today’s incarnation of the Russian state. One told us that at the beginning of events in Ukraine, he felt a bond with the Kyiv protesters because they were fighting police. Others echo the sentiment of many Russians by complaining of a country blighted by poverty, inequality and corruption. A not insignificant strand of thought among volunteers and mercenaries who returned from the Donbas is that the Russian government and state agencies betrayed those who traveled to risk their lives and fight. The view is that leaving the region in a frozen conflict rather than committing to a military victory and full annexation was an act of moral cowardice. Although this is not a view often expressed on RSOTM, the frequency with which it appears on other forums suggests this is likely to be common among Wagner fighters too.

But the central experience for the majority of Wagner soldiers is Syria, where the group has been engaged from 2016 to this day. An unknown number of Wagner mercenaries fought in two campaigns to defeat the Islamic State in Palmyra — at a cost of what one vet called “unjustifiably high” losses. Casualties were considerable, too, in Deir ez-Zor, from where a vet told us he was aware of 90 bodies flown back to Russia. The families are paid compensation, but vets who return home don’t qualify for military pensions and privileges — unlike members of the regular Russian military, who, according to the Wagner vets, were rarely seen in combat.

The vets recount that kit was sometimes substandard and in short supply. There were casualties as a result of Wagner personnel being hit by friendly fire from Russian warplanes. They had little respect for the Syrian army, who they say lacked backbone and professionalism. Russian representation of the Assad regime and the general situation in Syria was false, some think. They recognize that terrible atrocities were committed by Wagner personnel — and some express shock at the infamous killing, decapitation, dismembering and burning of an unarmed Syrian man in the Syrian desert in 2017, filmed by the Russian perpetrators themselves.

One vet gave us a harrowing description of the treatment of prisoners of war: “If a prisoner has any value or knowledge that might be useful, then he’s passed along to be worked on in more detail. But if it’s some common soldier then this is what happens. If a workforce is needed to dig trenches for example or to labor, then the prisoner … has value as a slave. If not, then the result is obvious. No one wants an extra mouth to feed.”

Yet for many Wagner soldiers, the Syrian experience provides a source of pride and a sense of achievement; a realization perhaps of Wagner’s self-representation as an appealing alternative to a bleak domestic life in all too often unemployment-ridden, far-flung parts of provincial Russia. Few consider the advancement of national interest abroad by military force as something unethical. Some argue that, with improved discipline, education and enforceable rules governing the treatment of civilians, the “office” could provide services just like other PMCs (Private Military Companies) or the French Foreign Legion.

And yet among Wagner soldiers there is an understanding that they are fighting not just for national influence, adventure and personal gain. When we asked one vet in whose interests he considered the organization works for, his answer was those of “oligarchs” and “businesses in the international market of oil production.” We were also told the following: “The organization has three statues. In each is a soldier shielding a child with his hand. If the architect had been honest and had represented the situation accurately, the soldier would have been shielding an oil platform.”

Some deployments, such as to Ukraine, provided little obvious financial incentive for the Wagner Group. In Syria and elsewhere, however, operations have presented opportunities to make considerable profit. Documents that have emerged, announcements by the Syrian government, comments by Syrian officials and press investigations have all indicated that a company widely considered connected to the Wagner Group has benefited from oil and gas production in sites won and guarded by Wagner personnel.

In December 2017, what appeared to be a draft contract between the Syrian government and the company most often connected to Wagner was leaked and published by the Associated Press. According to the document, this company, “Evro Polis,” was apparently in negotiations to receive no less than 25% of profit from oil and gas fields in Syria in return for securing and protecting them. Since then, Syrian officials have reportedly confirmed to journalists that the company had indeed signed agreements as part of a road map for the development of the electricity and oil sector in Syria. Evro Polis denied any connection to Wagner. In other countries — such as the Central African Republic and Sudan — other companies that investigative journalists have connected to Wagner have sought involvement in other lucrative natural resource extraction.

What kind of commercial motive Wagner’s Libyan operations may have is difficult to prove — not least because Haftar was ultimately unable to take Tripoli and seize power in the country. In the months following the failed offensive, Wagner units were reportedly spotted at oil fields both in the south and north of Libya, but they appear to have withdrawn to Sirte and Jufra, key towns on the de facto border within the country that emerged since Haftar and his forces retreated from Tripoli.

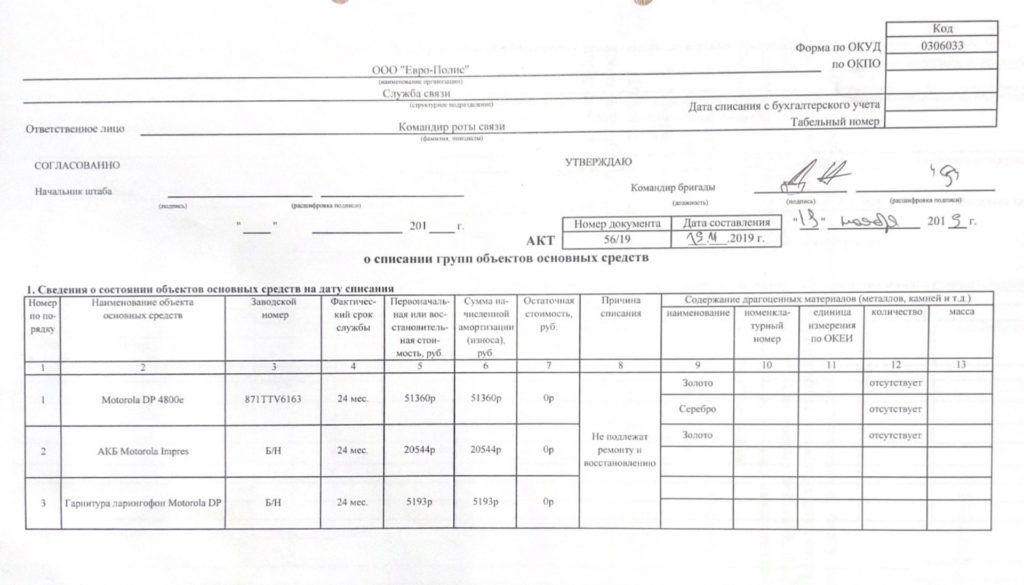

But thanks to an extraordinary series of documents we obtained in Libya, we have been able to connect Evro Polis to the Wagner operation in the country, gain a glimpse of how that deployment was part of wider activity across Africa and see fascinating, firsthand evidence of Wagner’s interaction with the Russian state.

The documents come from Libyan intelligence and consist of five pdf files, or 38 pages of paperwork, in Russian. Many bear burn marks around the edge. Perhaps their owners attempted to destroy them as they left; possibly they survived a fire caused by a strike on a Wagner HQ in Tripoli. According to contacts within Wagner and journalists familiar with Wagner paperwork, the style and content are consistent with other documents they have seen. They have no doubt they’re genuine.

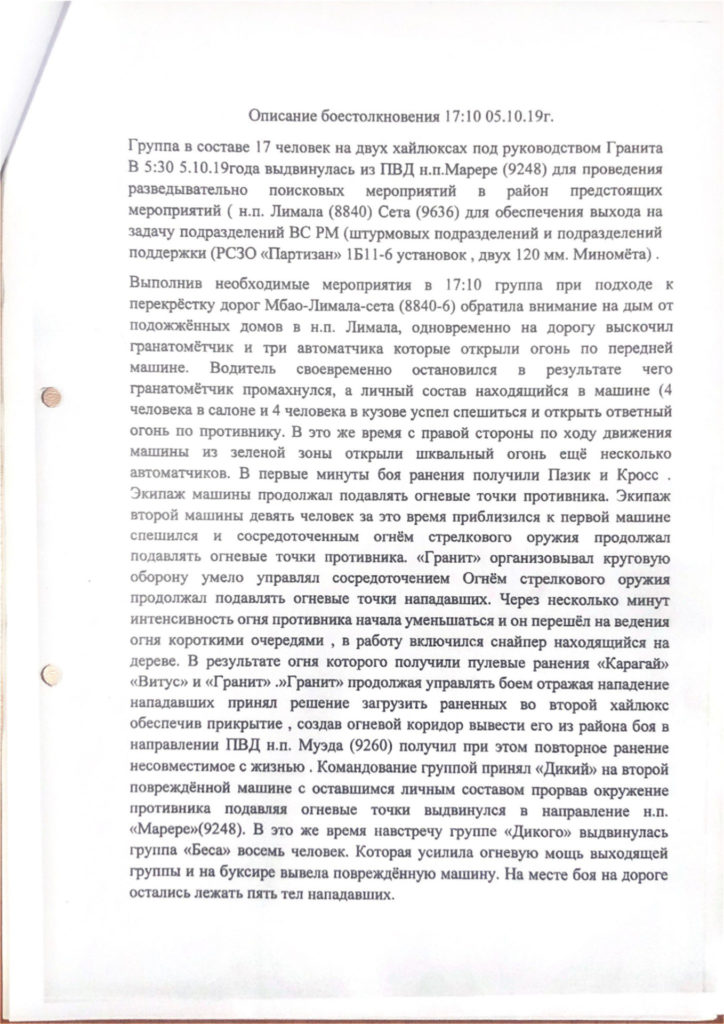

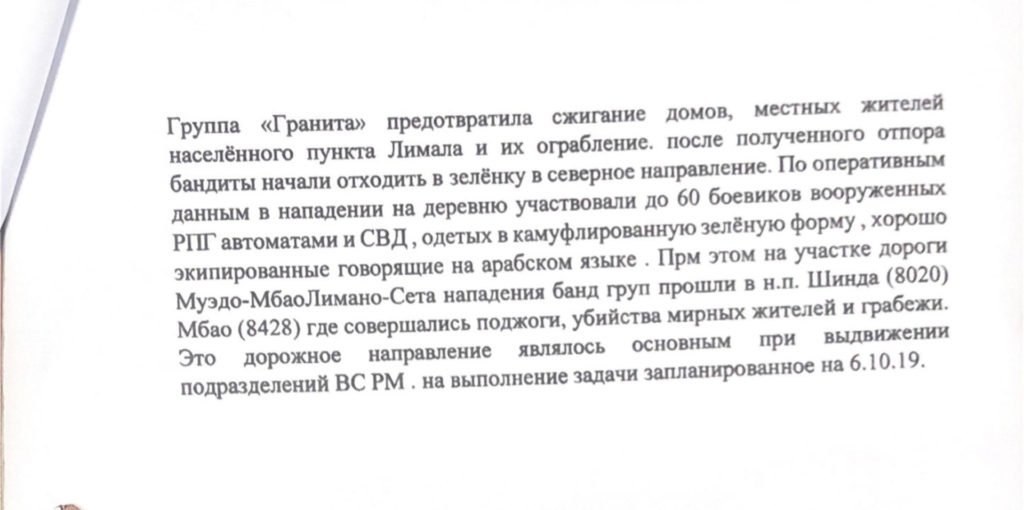

Several of the papers are dated November 2019 and are internal reports and accounting documentation telling the story of radio equipment used in operations at opposite ends of Africa. The trail begins with a detailed description of a battle between 25 Wagner personnel and militants operating in northeastern Mozambique in early October that year. Sketchy reports had emerged at the time of Wagner units fighting a growing Islamist insurgency in the impoverished Cabo Delgado region of the country. Local problems including resentment at multinational investment in offshore natural gas reserves offering little benefit to the local population had been fanned by an influx of Islamist militants reportedly connected to the Islamic State. One of the early providers of foreign military intervention to put down the unrest was Wagner.

The documents report an attack on a unit of Wagner soldiers by an estimated 60 militants. Reinforcements are called, but not before a unit commander called Granite is killed — his command taken over by his comrade Dikii (Russian for wild) — and two fighters, Pazik and Kross, are wounded. In addition, “the platoon’s communication equipment” is damaged beyond repair, as testified by Veterok (Breeze) and Bes (Demon) — respectively the head of communications and the commander of the mission in what is referred to as the “Minsk” direction. “M” for “Minsk” — the capital of Belarus — in Wagner parlance denotes Mozambique, just as the Volga town of Saratov is code for Syria, the Moscow suburb “Tsaritsyno” is the Central African Republic (both start with the same letter in Russian), while “Lipetsk,” a small town 400 miles south of Moscow, is Libya.

In the same bundle of papers, a report of the broken radios is made to Evro Polis. It’s signed by a certain “Zurab,” described as the “Commander of the Communications Platoon,” and by the “Brigade Commander” with the initials D.A. (or possibly D.U.), next to the mark “9.” As longtime observers of Wagner, such as Novaya Gazeta’s Denis Korotkov, confirm, Ninth (Девятый) is the code name for the military commander of Wagner: Utkin. The identity of Zurab is unknown, although the existence of this allegedly uninspiring individual within Wagner has been confirmed by different sources.

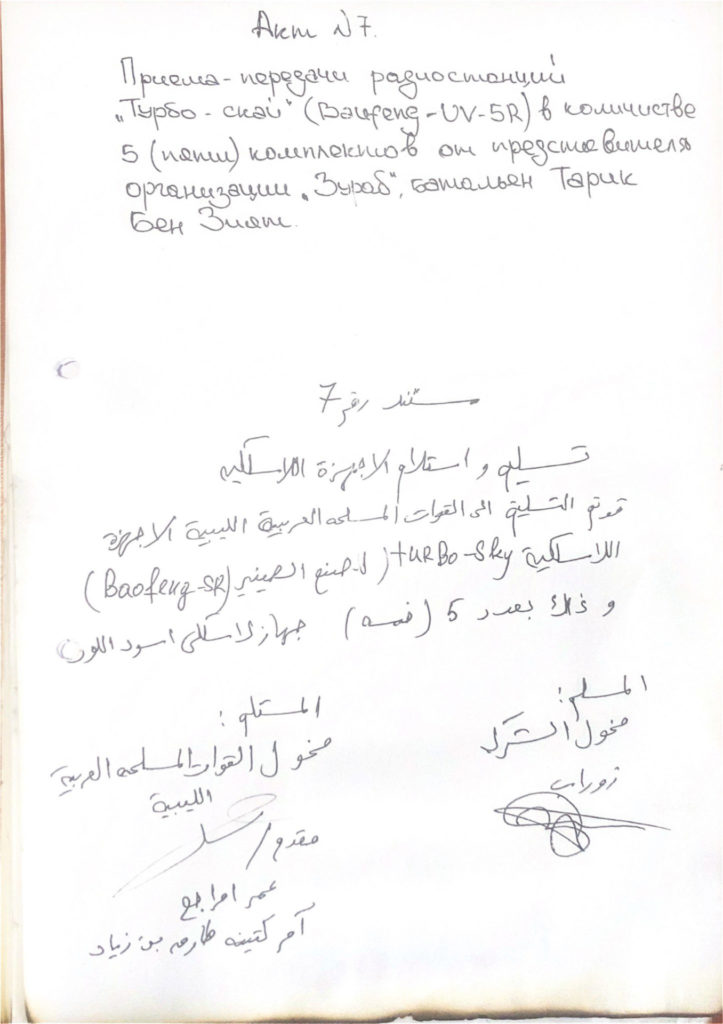

Another similar document follows, with details of further radio equipment that is also described as broken. And finally in a selection of handwritten receipts in Russian and Arabic, Zurab and seven representatives of Haftar’s LNA sign for the delivery of 189 Baofeng two-way radios. The notes appear to be documentary evidence of Russian entities connected to Evro Polis providing military aid to forces attempting to overthrow a government recognized and supported by the U.N.

Baofeng two-way radios are dual military and civilian purpose, but given the military recipients signing for the radios, the deliveries probably breach the U.N. arms embargo in Libya.

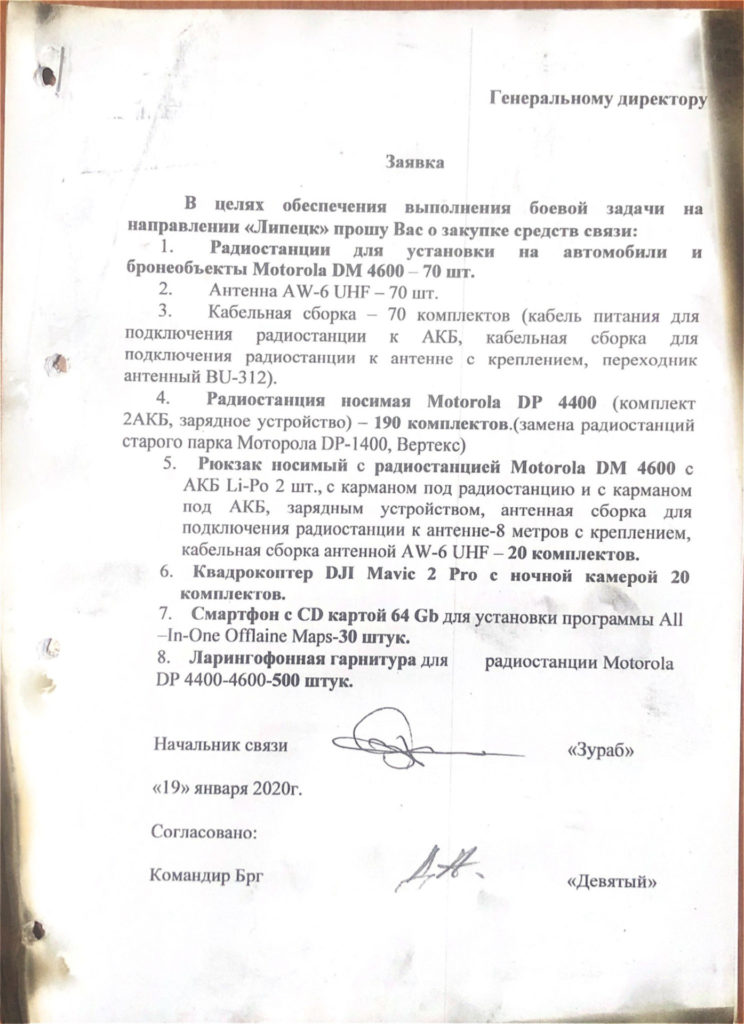

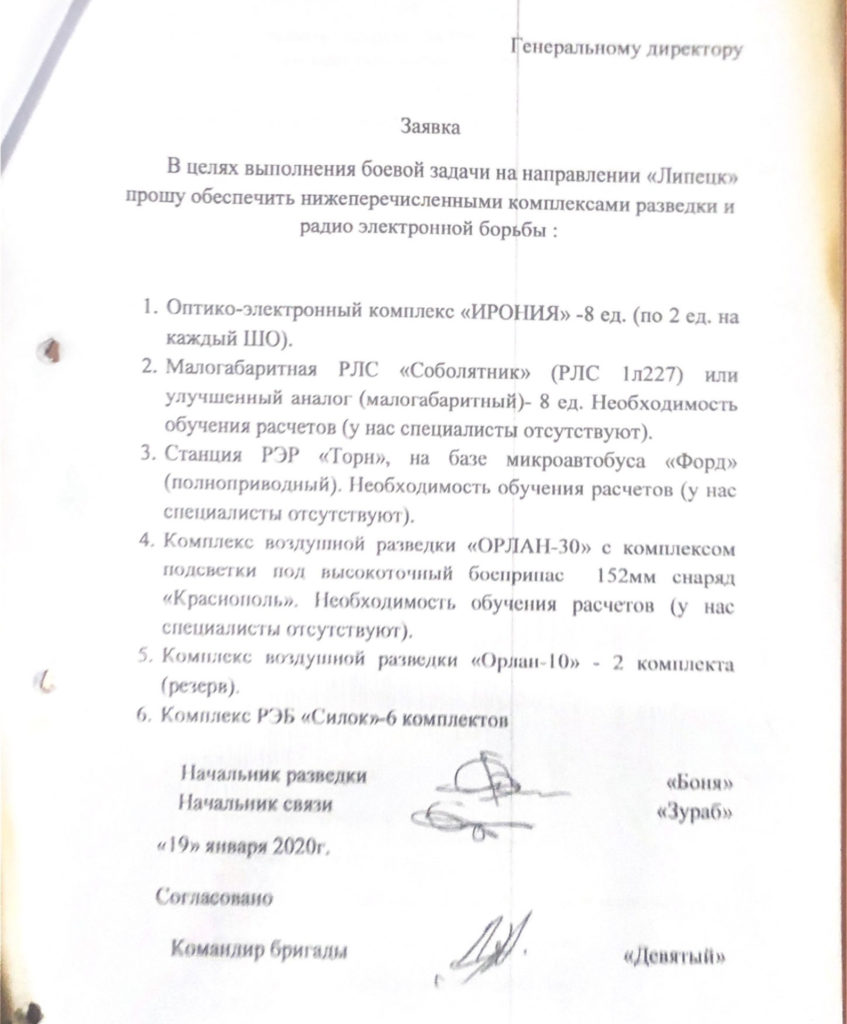

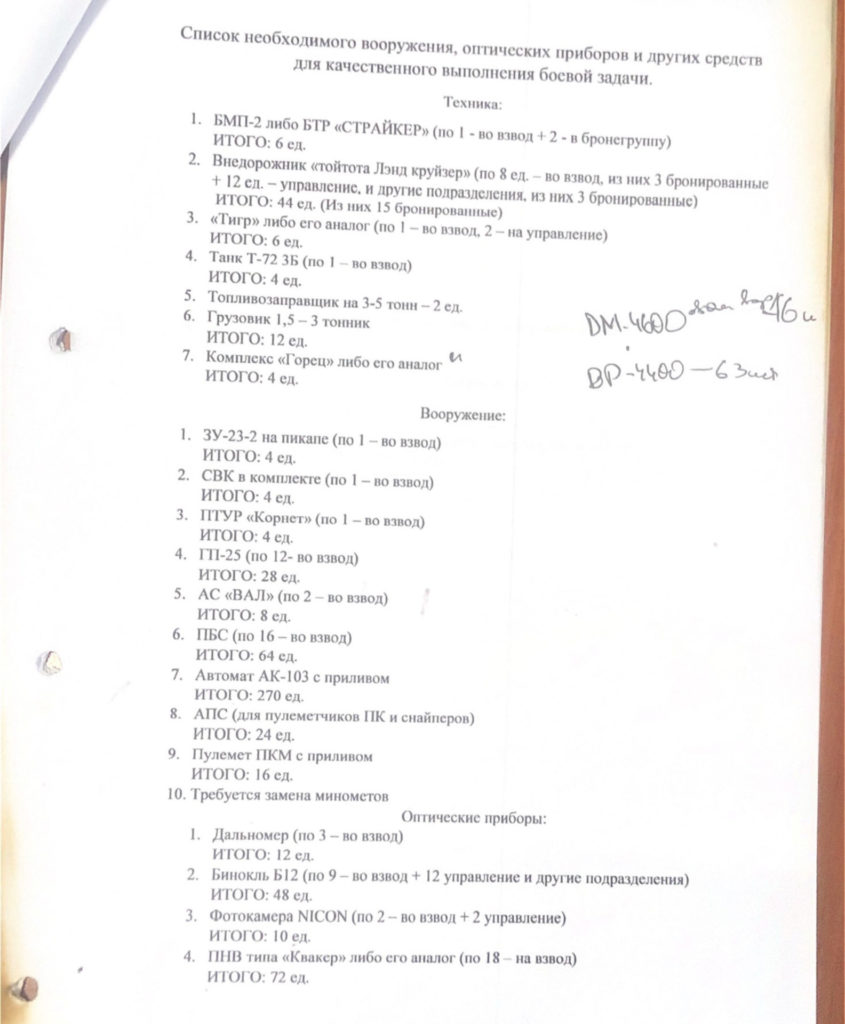

However, in comparison with the items listed on the largest, 10-page document we obtained, the Baofeng radios are child’s play. This document is a request to a “General Director” for well over 3,000 units of military equipment — together with tens of thousands of rounds — “for the completion of military tasks in the ‘Lipetsk direction.’” The document is dated Jan. 19, 2020, and signed by senior Wagner figures (using their code names).

Letters written to a so-called general director have been seen before in Wagner correspondence. According to Korotkov — whose coverage and understanding of Wagner are unparalleled — the general director is most likely someone whose name has often been connected to Wagner — the businessperson and close associate of Putin, Prigozhin. To Korotkov, the seniority of the document’s signatories — which include “Ninth” (Utkin) — suggests they could only be writing to someone at the very top of the organization’s hierarchy.

Prigozhin has been named as the suspected head of Wagner in numerous journalistic investigations. In the U.N. Panel of Experts report published earlier this year, he is explicitly named as being involved in the group. His companies Concord Management and Consulting LLC and Concord Catering have received contracts from the Russian Ministry of Defense over a number of years. Senior figures officially representing companies that have acted parallel to Wagner deployments, such as Evro Polis, have ties to Prigozhin’s business structure or security detachment. Planes thought to be linked to Prigozhin have reportedly flown to several destinations where Wagner subsequently became active, and Prigozhin was the only civilian present at a meeting between Haftar and the Russian defense minister, the Defense Ministry chief of staff and other top Russian military officials just months before Haftar launched his offensive on Tripoli. Prigozhin has repeatedly denied any connection to Wagner and did so again in response to questions we sent him during the course of our film.

In the 10-page document, the list of vehicles requested is impressive: six T-72 B3s, the latest Russian battle tank, in service since 2016; six BMP-2 infantry fighting vehicles; six Tigr armored and armed jeeps, also the latest such vehicle; and 44 Land Cruisers, 15 of them armored. Weaponry ranges from Kornet anti-tank missiles, heavy machine guns, mortars, flame-throwers to a total of 270 AK-103 automatic rifles with the same number of night-vision sights. Just over 300 sets of Ratnik-2 body armor, the latest used in the Russian military, 190 radio sets and 500 laryngophone headsets all also suggest personnel numbers well into the hundreds. Emphasis is also placed on updating radio equipment, requesting 70 Motorola DM 4600 radio stations for vehicles and 190 portable Motorola DP4400 radios to replace old versions. Several modern drones are also requested, with night-vision and bomb delivery capability.

But the most extraordinary aspect of this shopping list is the “radio-electronic warfare” equipment requested. Throughout we find listed state-of-the-art, Russian-made items that, according to press coverage, are only just becoming available to regiments within the regular Russian military. One page, “for intelligence and radio-electronic” warfare, is breathtaking in its ambition to obtain the latest surveillance radar systems, which detect and identify targets for artillery using laser and other means. Items requested include eight units of the vehicle-mounted Ironia optical electronic complex (two per Storm Unit); eight portable Sobolyatnik ground surveillance radars (which were only made available to Russian airborne units in June 2020); the latest military Orlan-30 drone; a TORN radar unit used for intercepting radio traffic; and six Silok anti-drone defense units.

We don’t know how much of the equipment requested in January 2020 reached Wagner units. However, Haitham’s description of Wagner capabilities in Ain Zara in March 2020 suggests their radio-electronic needs, at least, were met. Haitham spoke of Wagner disrupting communication, artillery and mortars used to great precision, and the ability to detect and destroy vehicles within minutes of them moving. Al-Juwaili also named the jamming capabilities of Wagner forces as a particular difficulty, rendering the use of drones over their positions impossible.

Meanwhile our Samsung tablet may also have benefited from the resupply list. Thirty smartphones with 64GB cards for installing the Offline Maps program are explicitly requested in the 10-page document. That is the same program that operates the map that so impressed Haitham when we showed him the tablet.

The prominence of state-of-the-art, radio-electronic equipment, modern communications and drones seems to indicate that by the end of January 2020, the Wagner units in Libya were facing significant and technologically advanced resistance. Instead of militias fighting from pickup trucks and old tanks, Wagner was contending with a force benefiting from advanced military equipment supplied in significant quantities by the Turkish state. It is striking that among three of the most advanced items requested — the Sobolyatnik and TORN radars and the new Orlan-30 drone — the Wagner commanders request instruction, citing the fact that “we do not have specialists.” The phrase smacks of a PMC feeling out of its depth in a hostile situation.

It stands to reason that instruction on how to use the latest equipment in the Russian armed forces would most likely have to be supplied by the Russian military itself. The same is true regarding the source of the weaponry itself. Some of the equipment requested in the 10 pages we obtained is widely available across the world. Yet the state-of-the-art kit on the Wagner list is accessible only to the Russian military — with some, such as the T-72 B3 tank, in service in Belarus as well.

That Wagner units have recourse to the good offices of the Russian Armed Forces seems self-evident. Novaya Gazeta has demonstrated that Wagner has used Ministry of Defense aircraft and ships for their operations in Syria. Wagner veterans have spoken or written about working alongside the military — however condescending they have perceived the attitude of the Russian state’s official military representatives. And the Wagner training camp in Molkino, southern Russia, is situated in immediate proximity to a GRU military base.

The documents we obtained are, as far as we know, the first paper trail to emerge indicating a direct supply of military equipment from the Russian state to the Wagner group.

However, the Russian state has steadfastly denied any connection with Wagner personnel and operations. Official statements relating to Libya claimed that individuals who had been named in the press as having fought there had never left Russia. By January 2020 — just a couple of weeks before the equipment requests are dated — Putin made the following, slightly more equivocal statement: “If there are Russian citizens there, they are not representing the interests of the Russian state and aren’t receiving money from the Russian state.” When we approached the Foreign Ministry, we presented the evidence we had gathered. We were told that “Russia is doing its utmost to promote a ceasefire and a political settlement to the crisis in Libya. Information about the presence of Wagner employees in Libya … is mostly based on rigged data and is aimed at discrediting Russia’s policy in the Libyan direction.”

Libya is divided, geographically and politically, much of the country controlled by forces loyal to Haftar and inaccessible to most journalists. To judge from the testimony of inhabitants of these areas, and from images that continue to emerge, Wagner personnel and Russian military equipment are still very much in evidence – despite a U.N.-brokered agreement reached by both sides in October last year that all foreign forces should leave.

And it’s not just Libya. Wagner has an established and significant presence in the Central African Republic, marked by allegations of grave human rights abuses. And in recent weeks the troopers have become more active and visible in Mali, too.