This piece was originally published in New Lines magazine’s Just Landed newsletter, which you can sign up for here.

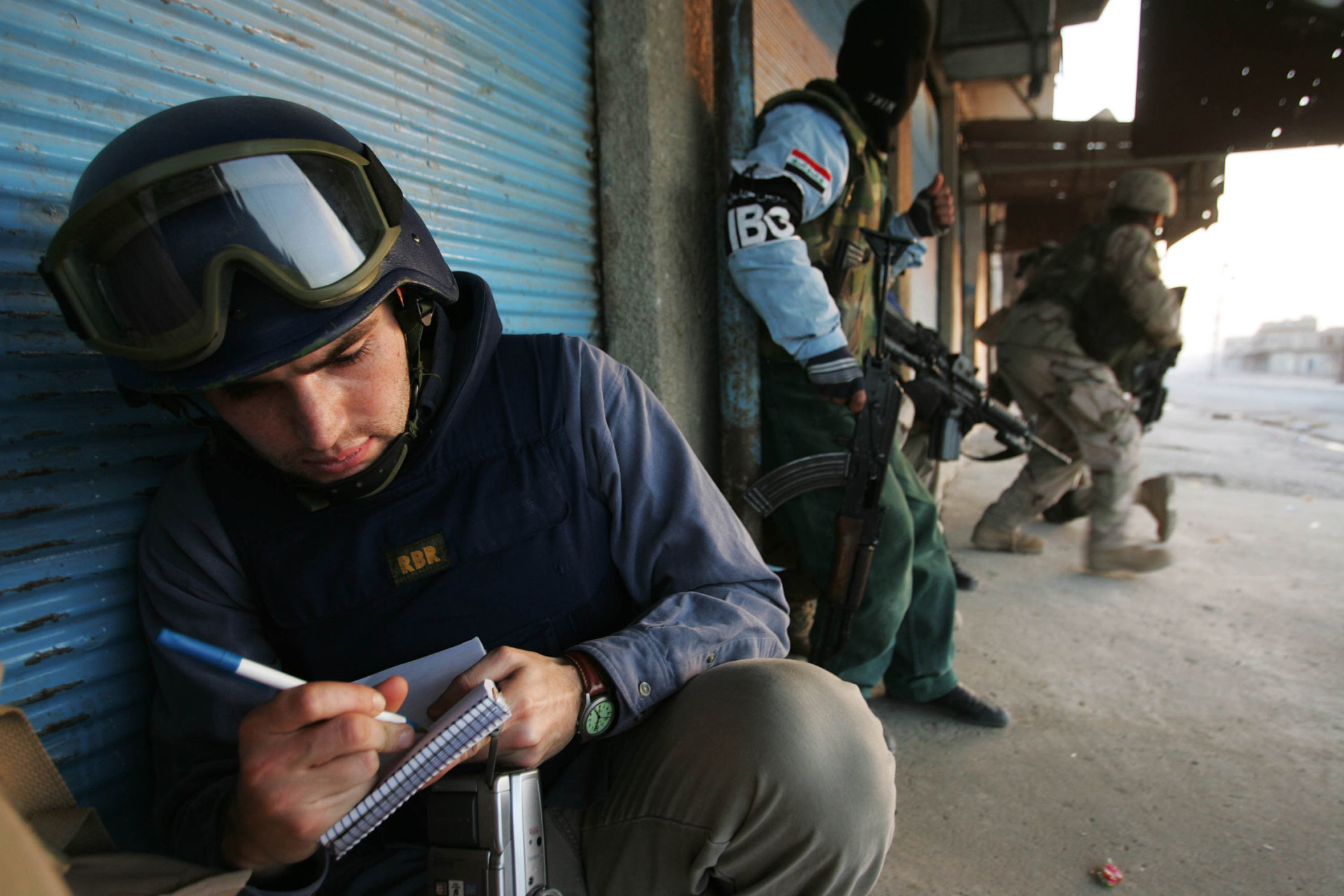

Being an international correspondent is exhilarating. You roam the world to cover the most important events. You take risks by going to places where no one else dares go. You come back to tell stories from those places. You get your hard-won recognition and your decent pay, then go home.

It’s also often a brave and noble choice—but it’s still a choice, and if you survive going down that path, you probably will be compensated for it in many ways.

But there’s a piece that somehow always appears to be missing from the glamorous spotlight under which a foreign correspondent is placed: the fixer, i.e., the one who ensures that the job gets done, that no one is hurt and that obstacles are surmountable.

Fixers have been in the spotlight the past few weeks. The death of Oleksandra “Sasha” Kuvshynova while embedded with a Fox News crew in Ukraine a month ago and the company’s initial inability even to mention her name may have ignited this conversation. Since then Sasha has become one of few local producers whose sacrifices are acknowledged as much as those of foreign correspondents.

There was also an article by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, which gave space to three different fixers to share their experiences. Instead of “fixers,” the institute encouraged use of the term “field producers,” the one that I shall hereafter use.

Kuvshynova was killed on March 14 near Kyiv while working with a Fox News team to cover Russia’s invasion. Pierre Zakrzewski, a veteran Fox News cameraman, was also killed that day. The loss of both journalists was grave and heartbreaking for their families and loved ones, for the journalism community and for the millions around the world who follow the news.

Fox News and other media organizations were not allowed to get away with leaving out the name of the local producer this time, even though they tried to do so. But that does not change the fact that overlooking or under-reporting the sacrifices of local field producers around the world has been the norm rather than a lamentable exception.

I don’t want us to be stuck with the why-did-we-not-see-this-in-Syria? debate forever, because the war on Ukraine and its victims deserve all the attention they should get, and international and local journalists alike are doing tremendous work together while risking their lives every hour of every day.

I do, however, find it urgent that we should use this momentum to raise the world’s awareness of what local field producers do and what they have often been robbed of.

Before I received the first of several slights from an international media company––when the news agency I risked my life to work for let me go right after I had to flee from Syria—I was told by a visiting BBC journalist that I should no longer call myself a fixer or a stringer. “You’re a field producer,” she said. “A journalist.”

I didn’t understand what she meant at the time. I had liked the word fixer because it described a person who gets things done, and I had not yet merited another title. But she meant the systemic erasure of local field producers from the annals of international war journalism, of which I had not yet been aware.

I requested not to be credited for virtually everything I did before leaving Syria. In fact, I even appreciated it when a foreign correspondent I worked with offered it to me but encouraged me against it at the same time, explaining the risks that may come with it. He made it clear that he was not trying to get rid of my name next to his and was speaking merely out of care for my safety. But I also found it strange when I was neither given any credit nor asked whether I would like that or not.

It should be up to the local field producer whether they want to be publicly credited for their role in producing a report or not.

And when field producers demand a daily rate of $250 to $500 for working with a crew of international journalists in a conflict zone, they are not trying to rob the crews; they are barely getting enough for the risks they take to do the work they do.

When roving correspondents pack up and leave a conflict zone after a satisfying or disappointing reporting trip, the local producer stays to face possible consequences. When an angry dictatorship chooses to refrain from hurting a foreign citizen on its territory—although it often does that too—it also considers taking that anger out on the people whose lives are less valuable: the local producers.

I was well out of Syria in 2018 when someone from the Ministry of Information there sent me threatening WhatsApp messages because he was dissatisfied with the coverage of another journalist at the same company at which I worked. For even after we leave those countries of ours, we are sometimes still considered the easier and less valuable target, both for the authoritarian regime and for the media that employs us.

Refraining from using the word fixer is fine, but I bet that there are other priorities that those journalists need first: acknowledge that they are often real journalists, just like you; give them the choice of whether to get credited for their work publicly or not; pay them decently; take measures for their security, ensuring that their lives are not less valuable than yours; and help them out when they call on you later seeking to leave their country of residence or find a job.

That could be a start.