At 9 a.m. on June 28, 2017, in the city of Ürümchi in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, I received a phone call from an official. I shall call her Güljan. She is a cadre of the Chinese Communist Party’s neighborhood committee, in charge of overseeing the residents in our apartment building. She told me that my wife and I needed to go to the neighborhood committee office in an hour and we should not be late.

Güljan, who is Uyghur, had just joined what is commonly called the “contractor cadre.” As a member of our neighborhood committee, she was tasked by the authorities to monitor our apartment building. Part of her job was to visit us in our home for the “regular checkup,” conducted twice a week. Her questions during these visits always started with whether we were having any difficulties in our household. She would then proceed to other queries, like did we host any guests from out of town or, more intrusively, if we had conceived any children outside of family planning. Also, did we have anyone praying in our household, she would remember to ask. She would record our answers meticulously in a notebook that she always carried on her person, all while scanning our apartment for additional information.

My wife, who is sociable, would chat with Güljan about all sorts of personal matters. Güljan graduated from university in 2014, and she could not find a job related to her studies at the university. (She never told us what she studied, and it was not convenient for us to ask.) Marginalization and distrust of the Uyghurs and other indigenous Muslims was getting stronger, and job discrimination was rife. Many Uyghurs graduate from university only to face anxiety about making a living. Without other options for work, Güljan finally decided to accept this contractor cadre position. The salary is low and the work difficult, but if she stuck with it, worked hard, and managed to pass the civil service exam, she would be hired as permanent staff, thus securing her livelihood. As far as I could tell, this was Güljan’s main wish. I sometimes saw her standing in front of an apartment building with a blue binder in her arm as if she were waiting for someone. Sometimes I saw her going in and out of different households at all hours. My wife, sometimes lamenting Güljan’s state of affairs, would say: “It is also difficult for these poor people!” There were many young people like Güljan working for our neighborhood committee. The government encouraged young Uyghur graduates who were struggling to find a job to work for these committees.

The mass arrest of the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, which had begun on April 25, was continuing. People were being summoned to the neighborhood committee office or the local police station with a phone call. They would be told they were “going to study” before being taken to concentration camps or, as they are also called, “re-education camps.” I asked Güljan why we needed to go to the office. She must have noticed that I was worried, so she tried to reassure me by saying that we just needed to fill out a form and “nothing else.”

Neighborhood committees are the CCP’s smallest unit for managing cities. For administrative purposes, a city is divided into district committees, which are further divided into street management committees, which, in turn, are further divided into neighborhood committees. No citizen of China falls outside this categorization system, but over the prior three years the neighborhood committees had been growing in significance and power. These committees used to consist of three or four people, barely attracting anyone’s attention. By 2017, they had grown to average 30 to 40 people. The police also bolstered their presence in these committees, designating liaison officers who divided their time between the police station and the neighborhood committee office. Neighborhood committees usually rent office space inside an apartment complex they are in charge of monitoring.

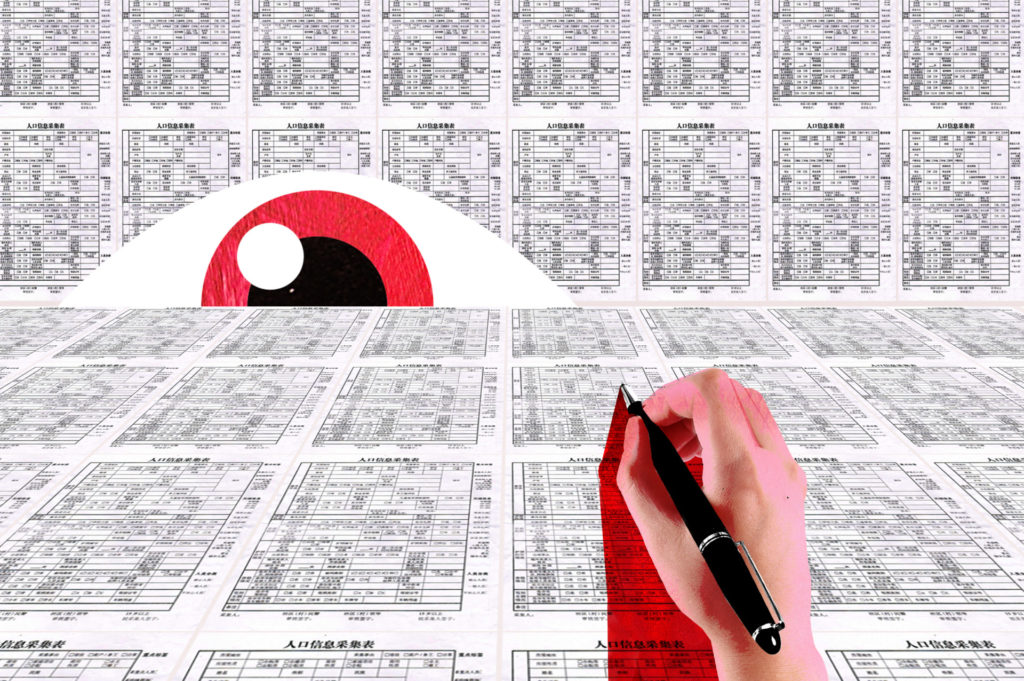

Their cadre are assigned the families and small businesses to monitor, and in doing so, they write up weekly reports and submit them to the neighborhood committee supervisors and the police. The main targets of these reports are usually apartment renters, people without permanent jobs, and pious Uyghurs, including anyone who prays five times a day, grows facial hair, or wears the hijab. Many in the community believed that the mass arrests happening in Ürümchi were somehow related to the reports filed up the chain of command by the committee cadre.

Each apartment building had a poster with the headshot and contact information of the police officers and the neighborhood committee cadre in charge. These posters noted that residents of these apartment buildings could reach out whenever they wanted for “any kind of problem,” including problems that may arise from neighbors monitoring and reporting on each other to the authorities.

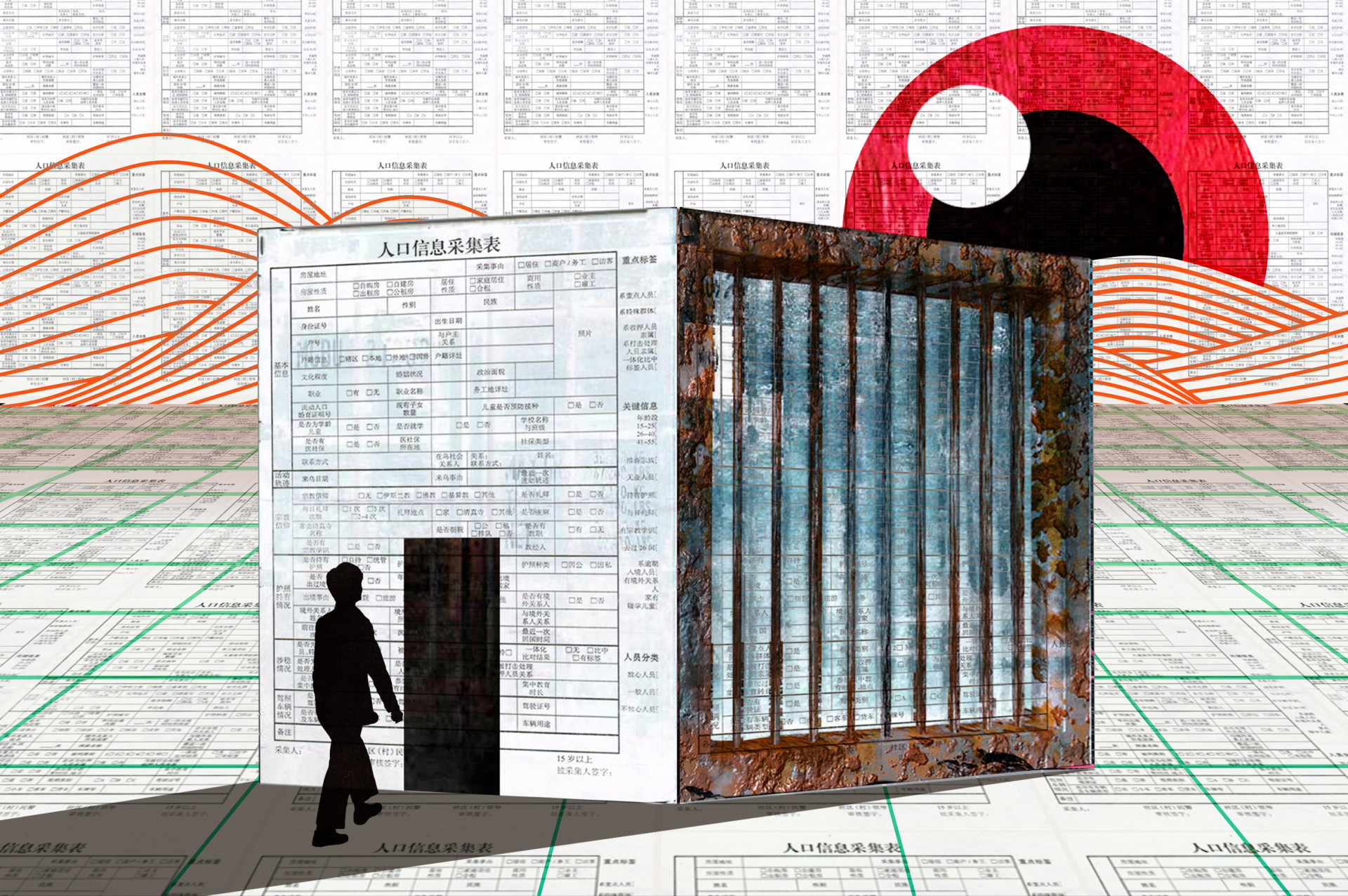

My wife and I arrived at our neighborhood committee’s office on time. It was a large space with many small offices, some belonging to the director and the police. Regular cadre worked at designated desks situated in the common area. There were not many people when we arrived, but Güljan was already there waiting for us. She promptly notified the police officer in charge — an Uyghur woman I shall call Adile. Anything that required police approval usually went through her first. Adile had also routinely visited us in our apartment to collect information, so we were already familiar with her. After we greeted each other, Adile handed me four copies of a form in Chinese titled: “Household Registration Information Collection Form.” Güljan explained that we needed to fill them out right away, then left us to the task and returned to her office.

I had heard about this form before; people in Ürümchi had filled it out since April. The rumor on the streets was that this form played a critical role in the mass arrests that had started at the end of April.

I also heard that the police departments in the region had established an internet-based system to collect people’s information. Commonly referred to as the Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP), this system became a tool for the police to mark people according to “threat level,” based on the information collected from the form. People fell into three categories: red for those deemed “dangerous,” yellow for “suspicious,” and blue for merely “untrustworthy.” Everyone’s government-issued identity card was linked to the IJOP, so whenever we crossed a police checkpoint that required an ID check, we risked arrest based on our designation, which was unknown to us. Uyghurs called these categories “dots.” So when someone was arrested we would say, “There was a dot on their ID; that’s why they were arrested.” Back then, most people believed that the form was used to collect information solely for the IJOP, for administrative purposes. Some of my friends were surprised to learn that, here we were in June, and I had not yet filled out this form. I, myself, could not understand the delay in my summoning to fill it out, and there was no point in wondering because no one was going to explain things.

At the neighborhood committee’s office, we sat down beside a giant desk in the middle. “We have to hurry up. Let me help you. I will fill out the form for you, and you can each fill out the form for your two children. I have your basic information, but I will ask you for what I don’t know,” Güljan said, eager to rush us through the process. She sifted briskly through her blue binder and found our family’s information, then started filling out the form on our behalf.

The one-page form consisted of six different categories, starting with the straightforward “Basic Information” section: full name, address, ID number, occupation, and number of children. Then came the “Activity Permission” section, which inquired about the date of one’s arrival in Ürümchi, the reason for this arrival, and the activities conducted in the city. After that came the “Religious Practices” section, inquiring about the religion one believed in, their practices, whether they prayed or have been to Hajj, whether they possessed religious knowledge, and, if yes, where was it learned and whom was it learned from. It also asked if one had been abroad and, if yes, how many times, the physical location of the passport, and a list of contacts, if any, overseas. It was clear that this was an important section.

After that came the “Passport Usage” section, which collected passport information like international travel history, the reason for such travel, and whether one had been to any of the 26 countries on the “terror list” — a list that was presented to us later in the interview.

The following section, “Information Regarding Stability,” inquired whether one was marked in the IJOP as having a criminal history or was related to someone with a criminal history, and whether one had attended a concentration/“re-education” camp and, if yes, the location of the camp, date, and length of stay.

The final section, “Driver’s License and Automobile Usage,” asked for one’s driver’s license and personal vehicle information.

On the right top corner of the form, there was a small section titled “Critical Signs.” Inside it, and tightly listed together, were the subsections “Critical Person,” “Special Group Member,” “Relative of Detainees,” “Relative of Crackdown Target,” and “Marked in Integrated Joint Operations Platform.” Below, there were boxes to check: “Critical Information” along with “Uyghur,” “Unemployed,” “Has a Passport,” “Prays Every Day,” “Has Knowledge of Religion,” “Traveled to 26 Countries,” “Spent More Time Than Allowed Abroad,” “Has Contact Overseas,” and “Children Discontinued State Education,” listed with big spaces again. Anyone filling out this form could immediately understand that these 13 categories listed under “Critical Signs” and “Critical Information” would be used to assess one’s political credit. The boxes that followed those categories were for affirming the category and would take points away from one’s political credit. “Categorization” was at the bottom corner; “Trustworthy,” “Ordinary,” and “Untrustworthy” were listed. They were also followed by space for marking. These three categories were the conclusion of this entire form, and also the most important part of it. According to the rumors that were spreading in the city, if one was labeled “Untrustworthy,” or even “Ordinary,” they would be detained and sent for “studying.”

“What religion do you believe in?” said Güljan, suddenly with a strange look on her face. She was filling out that category. “None,” I said with certainty. My wife immediately turned her head to me with shock. “We don’t believe in any religion in our family,” I added. Güljan looked at my wife. My wife understood me at this point and nodded her head as a concurring response, but she could not say, “No, we don’t believe in religion.” Even though Güljan was aware of us lying, she continued to fill out the form without verifying our claim. At this moment, Adile came out of her office and came to us. She stared for a little while at the form that we were filling out then returned to her office.

“Have you ever been to any of the 26 countries?” Güljan asked me. “Which countries are those?” I asked her. She pulled out a sheet of paper from her binder and handed it to me. It was written in Chinese, “26 Countries That Are Related to Terrorism” and included the following countries: Algeria, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Egypt, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Kenya, Libya, South Sudan, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Syria, Yemen, Iraq, Iran, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Russia, and the United Arab Emirates. In other words, the Chinese government potentially put a terrorist label on any Uyghur who had been to any of these 26 countries. For the Chinese, these countries were the source of terrorism as well. “When we went to Europe with a tour group last year, we went through Turkey,” I tried to make Turkey sound like an insignificant stop of our trip. Indeed, when we went on a 15-day tour to five European countries including Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France, we had to spend one night in Istanbul and took a flight to Rome the next day because there were no direct flights from Ürümchi to Italy. And on our way back to Ürümchi, we went from Paris to Istanbul and spent a couple of days in the Turkish city. We did not tour much in Istanbul but rather were given time for shopping since the Uyghur people were fond of Turkish goods. “It also counts,” said Güljan without looking up, appearing arrogant and certain. This type of rude arrogance was often displayed by the Communist Party cadre and the police. I was stunned by her sudden crude response since she usually seemed like a newly employed, shy, and insecure person. I felt defeated.

After we filled out the form, Güljan inspected every detail meticulously. Then, we signed our names.

It was noon when my wife and I left the neighborhood committee office. We walked home. My wife quietly uttered, “Oh Allah, please forgive us!” I also said the same inside. It somehow lifted some weight of the guilt I had been feeling.

There were a few more worrisome events around the time that we filled out the form. Many of my friends and acquaintances were detained, one by one. I sensed the danger of detention as well, which put my family under threat.

After much hesitation, we finally decided to leave China.

On Sept. 25, 2017, my entire family, my two daughters, my wife and I, arrived in the United States on a tourist visa. Soon after, we submitted our asylum application to the U.S. government, like so many other Uyghurs.

Then, we started a new life in a completely strange land.