We had been scanning the horizon for hours in search of the doomed boat. It was June 27, 2022, and the news had come to us via Alarm Phone, a network of activists and civil society actors who run a hotline for refugees in distress in the Mediterranean Sea. I was on a Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders, or MSF) search and rescue ship named Geo Barents. We had doubled the shifts on the bridge of the boat as we neared the most recent coordinates given us for a possible rescue. Around 5 p.m., the radio crackled with urgency.

“MSF team! MSF team! Let’s get ready for rescue. Let’s get ready for rescue.”

The sunlight on the sea’s surface created a golden corridor leading straight to a black dot. It was the boat we were looking for. The MSF vessel soon reverberated with the sound of footsteps rushing down the deck. All hands were prepared for the rescue. I put my gear on — waterproof trousers, lifejacket and a helmet — and grabbed my camera. I was serving as the ship’s media manager, tasked with giving visibility to the plight of thousands of migrants crossing the Mediterranean in unseaworthy boats to escape war, terrorism, extreme poverty and political persecution.

The search and rescue team huddled in a circle to rush through a rescue plan. We split into two groups. Inflatable boats were launched from each side of the vessel and we prepared to embark. Our eyes were on the survivors.

“I don’t like what I’m seeing.”

The statement came from one of our most experienced search and rescue personnel. It only heightened the sense of apprehension. I didn’t ask questions. I was trying to convince myself that, however difficult the situation, we could manage it.

We heard the desperate screams long before we approached the sinking boat. We could see groups of people in two different areas in the water. Our first boat approached the severely deflated white rubber dinghy with tens of people clinging to it, while the second went ahead to where three more people and a baby were trying to stay afloat on a wooden panel that had once served as the floor of the collapsed dinghy. The survivors were in mortal panic, suspended between life and death.

The search and rescue team rushed lifejackets to the survivors and instructed them on their use. Some survivors were still sitting on the half-deflated sponson, while others were trying to stay afloat in the void, where the floor of the boat had once been. On the detached wooden floorboard, a man held a baby on his shoulder while trying to balance himself along with two others.

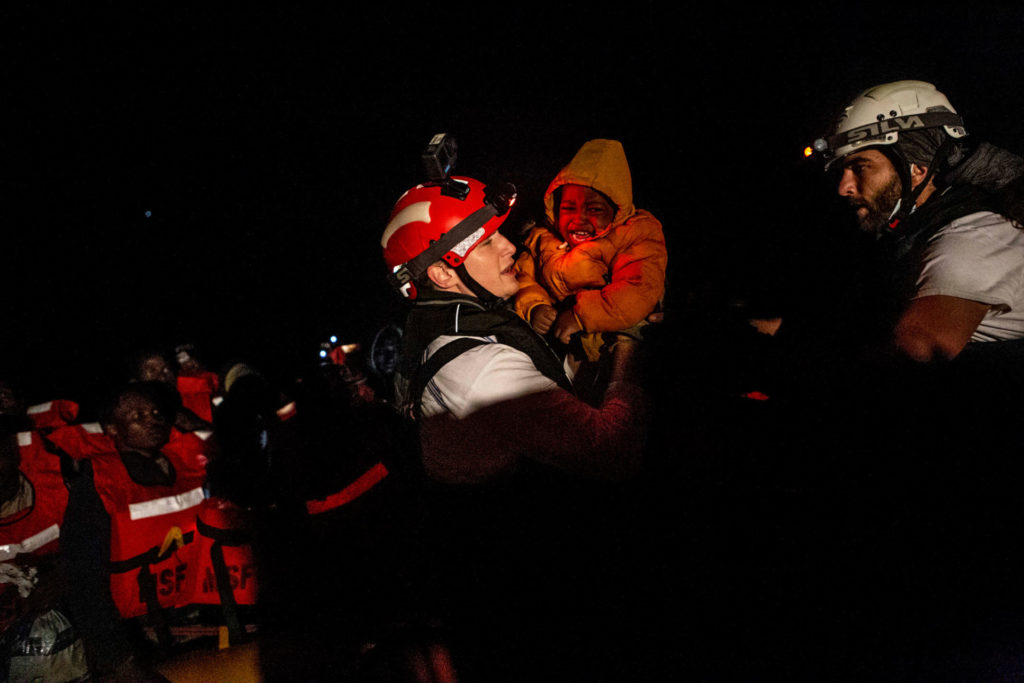

The second inflatable rescue boat had finally reached the survivors on the floorboard. The 4-month-old baby was pulled in first, but he had no vital signs. The team rushed the four survivors to the mother ship, where a medical team awaited. The rescue continued with the other 67 people.

Toward the end of the rescue, one man implored us to look at the water behind the deflated boat. We couldn’t see anything, so we navigated in that direction. What the man had been pointing at was a woman with a bright pink top. The sight of the woman’s face in the water made me freeze momentarily. Even though I understood that, as part of the rescue missions, I might one day have to face a situation like this, there was no way to prepare for the shock.

It took all five of us to pull the woman up from the sea into the inflatable rescue boat. Her eyes were wide open, and her mouth was foaming. The nurse and I performed CPR until we reached the Geo Barents, hoping we could bring her back to life. With the help of a stretcher, we transferred her to the mother ship, where she could receive further medical assistance.

By this time, all those we had rescued were safely aboard the Geo Barents. But our work was not yet done. For the two and a half hours until sunset, we traversed the waters in a hopeless search for survivors and bodies. The desperate voices of the frightened migrants had given way to an eerie silence; the blinding afternoon light was slowly replaced by a rich glow that went from gold to crimson. The Mediterranean was taking on the aspect I had adored as a child growing up in Greece. With the adrenaline from the past two hours subsiding, my mind finally registered the enormity of what had happened. I tried to get my thoughts together and focus on the search. Until that fateful afternoon, it was inconceivable to me that the same sea that had filled our summers with wondrous sights, enriching our memories, could also turn into a treacherous graveyard.

By 9 p.m., the light had faded, and we pulled up the inflatable boats to return to the Geo Barents. I asked with some trepidation if the baby had made it. I was told he was alive and in stable condition. I asked after the woman. She had died — and she had been pregnant.

We pressed on with our mission. We gave people dry clothes, blankets and some food. In other rescues, we would put on music to lift morale. But this time was different. The atmosphere was heavy. The survivors were starting to fall asleep, exhausted by the long hours they had spent at sea. The hours passed and, at around 2 a.m., it was my shift on the deck. The job at that hour includes making sure that facilities like toilets, trash cans and water taps are clean and functioning and, in case of an emergency, calling the medical team. That night, I saw people lie down with their eyes wide open, still in a state of shock. Others cried alone, silently. It was a moment of grief that they desperately needed.

The next morning, when people were rested and fed, we tried to occupy them with creative activities to get their minds off the previous day’s traumatic events. We took some threads and beads to the women’s section so we could make bracelets with them. I noticed a young girl who sat away from the rest of the women. Blessing — whose name has been changed to protect her identity — was then 16 years old, originally from Nigeria and the only English-speaking woman among Francophones. I sat with her and tried to engage her in conversation. I asked her what she likes to do in her free time. I asked about her life in Libya. She replied with the shyness common in girls of her age, looking at the floor often and awkwardly threading her bracelet. She was picking out beads with letters and arranging them into a name. I asked her what she wanted to do when she grew older. She said she wanted to become a fashion designer and name the company after her son.

“Oh, you have a son?”

She smiled uncomfortably while staring at the floor.

“I had a son. But he was lost in the water yesterday.”

The name on the bracelet was her son’s. The son had been born of rape in Libya, but he was precious to Blessing, as she had grown up an orphan.

Hers was not the only child lost that day. Survivors told us 30 people had died at sea on the day of the rescue, many of them minors. Another woman lost both her children. According to the International Organization for Migration, approximately 25,000 migrants have gone missing in the Mediterranean since 2014. Of them, almost 1,000 were children.

We said goodbye to Blessing and the other survivors in Italy a few days later. The body of the deceased pregnant woman was carried by the MSF team to shore, where a wooden coffin awaited her. My colleagues gathered reverently in a circle and hugged each other in silence. I watched from the window of the ship’s clinic, where I hid from everyone. I could only process this experience alone.

It is early evening in Bucharest, where the rustling of leaves outside my window signals the arrival of autumn. It has been three months since the Mediterranean tragedy and I’ve been in Romania to support the Ukrainian refugee response. The room has been my home and a bedside lamp my only source of light. Things are easier. Ukrainians are fleeing the horrors of a merciless war, but there are no barriers to entry here. Ukrainian refugees are welcomed at the border with warm smiles, hot food and free bus rides. The U.N., NGOs and EU are providing generous assistance to those taking refuge in Romania. There are no barbed wire fences or gunboats here to force desperate people back. Ukrainians I speak to are moved by the compassion with which they are received.

My phone buzzes and a WhatsApp message lands on my notifications.

“Can I call you?” reads the message.

It’s Blessing, the young Nigerian woman I had met on the boat. We have kept in touch and she messages me often. She now lives in Italy. To be there was once a dream, one that compelled her to make the perilous journey across the Mediterranean. Now, however, she lives at a shelter for unaccompanied minors somewhere deep in the rural south. This is the first time she has asked to speak on the phone.

“How are you?” I ask.

“I’m fine,” she replies in a sullen voice.

“Are you sure?”

She pauses.

“I’m not fine.”

Another pause.

“Today, I was going back from school and I saw a lot of children in the playground. Some the age of my son. They were playing football. He used to like football. It was very painful to see,” she says.

She bursts into tears. Every mention of her son feels like a stab in her heart.

“The reason I cannot sleep at night is because I don’t want to have bad dreams. So I keep myself from sleeping,” she adds.

I cannot find any words to make her feel better. All I can do is quietly pray that one day we can treat refugees in the Mediterranean with the same humanity and compassion we have shown those displaced in the brutal war instigated by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.