This past summer in Ceuta, the Spanish North African enclave, it felt like the temperature kept rising. The land border had been sealed since March 2020. Morocco closed it because of the pandemic, but as borders elsewhere reopened, it stayed closed, suffocating the economy. Then, over three days in May, came the arrival of 10,000 migrants, swimming out and around the border wall between the two countries. Ceuta was a pressure point in Spain-Morocco relations.

Meanwhile Vox, Spain’s far-right party, was baiting the city’s Muslim community. In the weeks leading up to Eid al-Adha, it tried to hamstring the celebration, which is a public holiday in Ceuta, on the grounds of public health. Before that, the local assembly had been suspended for weeks when Vox’s spokesperson began calling Ceuta’s Muslim representatives “fifth columnists” of Morocco. The insinuations about the community’s true loyalties were constant.

This might seem unsurprising, just another manifestation of the far-right phenomenon in Europe. But it wasn’t always this way. There was a time when the Spanish far right, in another incarnation, needed Ceuta’s Muslims and plied them with gifts. One of these, the Muley el-Mehdi mosque on the Avenida de África, was built in the middle of the Spanish Civil War. Behind the gates, in its shaded entrance, there is a dedication, in Spanish, then Arabic.

“and when the roses of peace bloom, we will give you their best flowers.”

Francisco Franco, April 3, 1937

Ceuta is a small territory in a strategic place. A matter of kilometers from the Iberian Peninsula, it watches over the south side of the Strait of Gibraltar. It has been through many hands, but it has been Spanish since the 17th century. It was an isolated fortification from then until 1912, when the Spanish protectorate was established. Ceuta became a launching pad for Spain’s colonization of North Africa.

Franco, the man who would become Spain’s dictator, arrived in Africa the same year. He was young and ambitious. The path to promotion was through action, so he joined the newly formed Regulars. These were Moroccan troops with Spanish officers, and they were often on the front line.

At the time, the Spanish protectorate was barely under Spanish control. From 1913 to 1919, Muley Ahmed el Raisuni, a leader of the Jebala tribal confederacy, fought a guerrilla war against the Spanish. Then, in 1921, Abd el-Krim united the tribes of the Rif and inflicted a terrible defeat on the Spanish at Annual, routing their army. The Spanish lost more than 10,000 men. Abd el-Krim went on to fight Spain to a stalemate in a five-year war, until the French and Moroccan armies joined the Spanish and forced him to surrender.

These years of war in the protectorate were formative for Franco, and they established the Regulars as a source of pride for the Army of Africa. But the disaster at Annual created a rift between the political and military establishments that would eventually lead to the Spanish Civil War. In 1936, Ceuta was once again a launching pad for an invasion. Franco took the Army of Africa to the mainland — along with 80,000 Regulars.

The entrance to the Regulars’ barracks in Ceuta is formidable. Up a slight slope, the medieval-looking battlements tower above. Two pieces of artillery point down toward the approach, and soldiers watch you with hands on assault rifles. Inscribed into the stone overhead is a phrase one sees often in Ceuta: Todo por la patria — Everything for the fatherland.

Inside, the barracks is a complex of red-and-white buildings from the 1920s, in the neo-Moorish style of the time, with horseshoe arches and arabesque tiling. The day I went, they were preparing for a parade, and dozens of soldiers were milling around in uniform, wearing the distinctive red cap that recalls the Regulars’ Moroccan origin. The Regular showing me around was a non-Muslim woman from Algeciras, a port city in Andalusia. “At first maybe 90% of Regulars were Muslim,” she told me. “Today, it’s more like 30 or 40%.”

When I told the guide I was writing a piece about the Regulars and the history of Ceuta’s Muslim community, she pointed out the neighborhood next to the barracks where, in the time of the protectorate, the soldiers’ families lived. While the men were off fighting, their wives and children received a level of health care and education. They also were protected from reprisals because they were, in a sense, fighting against their compatriots, or at least those who shared their faith.

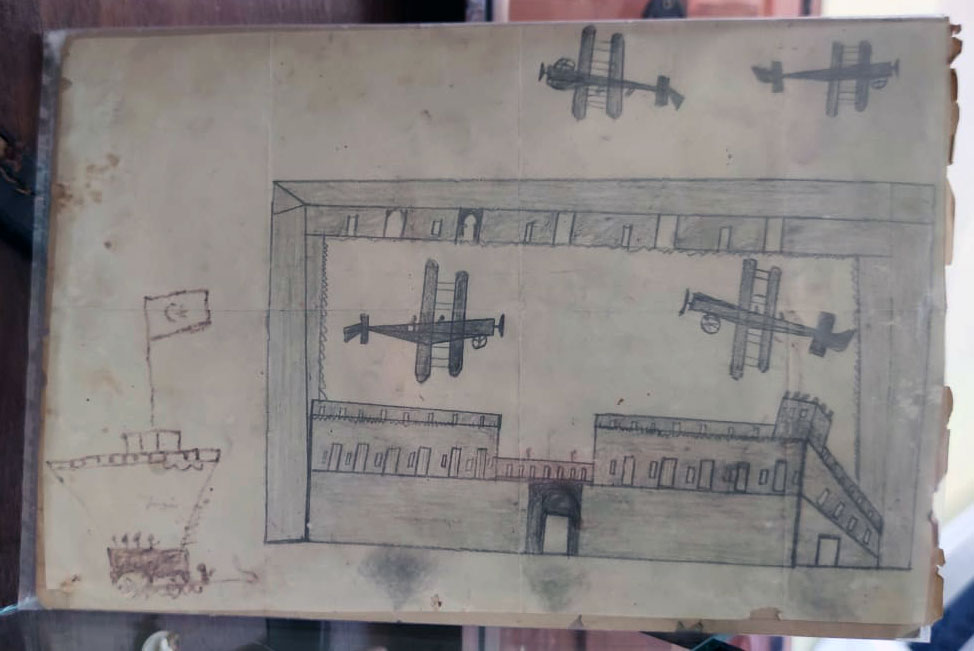

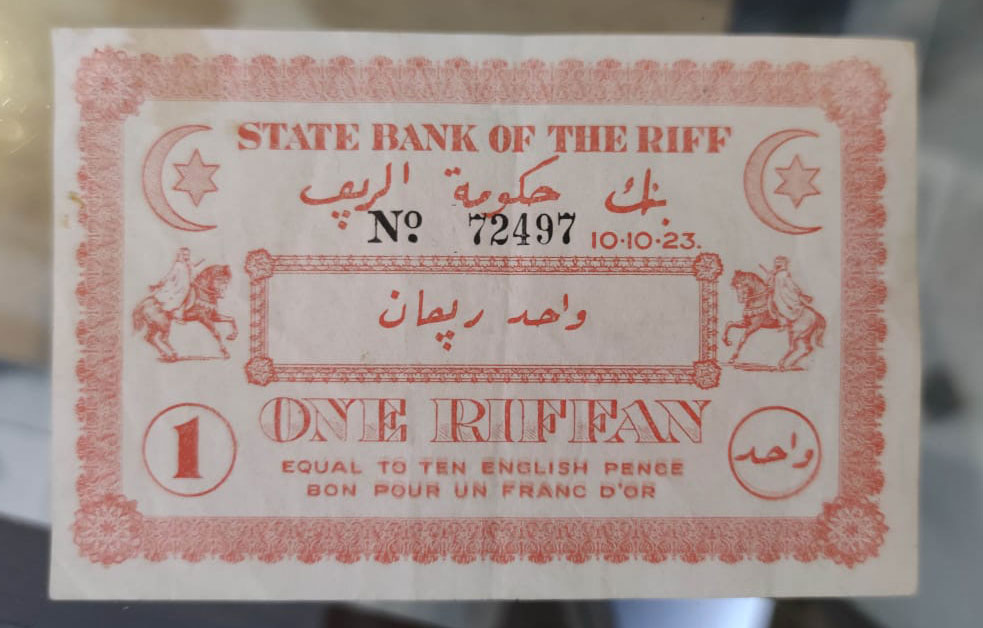

In the barracks museum, some items highlighted this tension. One glass cabinet held the trophies of war taken from Abd el-Krim’s home in Ajdir. They included a child’s sketch of the airplanes that terrorized the Rif with bombs and chemical weapons as well as a prototype bank note that was drawn up for the short-lived Republic of the Rif, but never issued.

Pride of place in the museum was given to the Sala de Heroes. It smelled, strangely, of anesthetic cream. The guide told me that the Regulars are the most-decorated unit in the Spanish army. They’ve received more than 200 medallas individuales: decorations for exceptional valor. She drew my attention to a Muslim name.

Not far from the barracks, Dris Ahmed Amar, president of an association for veterans of the Regulars, told me that much of the Muslim community in Ceuta is descended from Regulars. He himself was a third-generation Regular: His grandfather died in the Rif War, fighting against Abd el-Krim, while his father survived the Spanish Civil War. He gestured around the association’s cafe, half full with men smoking and drinking coffee. “And all of them, too: Regulars. Or sons, grandsons, great grandsons of Regulars.”

The walls were covered with medals, certificates and photos. When veterans die, Dris said, they often leave their memorabilia to him. There were shots of Regulars in the ruins of Madrid during the Civil War and on Germany’s eastern front in World War II, where volunteers fought alongside the Nazis. Another showed Franco’s personal guard, made of specially selected Regulars. (“He slept well with them around,” said Dris.) Then there was a series of mugshots of new recruits, each with a number pinned onto their chest. That’s how they were identified, Dris said: by number, not name. If they died, the number would be reallocated.

Dris alternated between pride and a sense of injustice. He and others I spoke with made much of the bravery of their forebears and the sacrifices they made for the country. But they saw this as detached from the cause — from Franco and the dictatorship, which in their eyes first abused, then abandoned the Regulars.

During the Civil War, 80,000 Regulars went to fight in Spain. Dris claimed, as others have, that they were recruited by force. The Spanish historian Maria Rosa de Madariaga has questioned this view, arguing that it was voluntary and fundamentally an economic decision. Many came from poor parts of the Rif, where there had been years of bad harvests. They joined to be fed and to receive a salary.

Recruitment was helped by a propaganda campaign that framed the Civil War as a crusade of the faithful against the godless. “Our war is a religious war,” said Franco. “We who fight, whether Christians or Muslims, are soldiers of God and we are not fighting against men but against atheism and materialism.” Tribal and religious leaders, such as Muley el-Mehdi, took this message to the Moroccan population of the protectorate. “And when the war finished, Franco made that gift to him,” said Dris, pointing down the hill. “He gave him a mosque with his name on it.”

On the mainland, the Regulars were disproportionately used as vanguard troops and suffered many casualties. Of the 80,000 that went, 11,500 were killed and 55,000 sustained injuries.

After the Civil War, in 1939, the Regulars returned to the protectorate. Most were demobilized. Those disabled in the conflict were referred to by the Francoist state as the “glorious mutilated.” They received a pension — smaller than that received by their Spanish counterparts but more than the defeated Republican veterans.

Though the regime no longer needed so many Muslim soldiers, it continued to prioritize the appearance of paternal generosity. It was, particularly after World War II, isolated in Europe, and it sought allies among the Arab nations. For that, it wanted to show how well it treated its Muslim veterans and subjects.

Each year from 1936 to 1951, the regime paid for 300 Muslims to undertake the pilgrimage from Ceuta to Mecca. It equipped a steamship with a prayer room specifically for this purpose. Often, on the way back to Africa, the pilgrims would make stops in Seville and Córdoba. Sometimes Franco himself would appear and tell them how Andalusia ought to be a second Mecca for them. As Eric Calderwood describes in his book, “Colonial al-Andalus,” the regime used al-Andalus as a geopolitical construct that both justified the Spanish presence in North Africa and differentiated it from the French colonialism in the region.

Central to this was the concept of convivencia: the idea that Christians, Muslims and Jews once lived in harmony in al-Andalus and could again, in the protectorate. Some visitors, won over by the romanticism, believed it. The day-to-day reality was rather different. Despite the tolerance of cultural and religious customs, it remained a relationship of tutelage between colonizer and colonial subjects.

In 1956, France left its protectorate in the south of Morocco. Spain followed suit in the north, but it kept Ceuta and Melilla, two territories that preceded the protectorate, as well as the Western Sahara.

At that time, Ceuta’s Muslims faced a choice. Religion was not the only force driving Moroccan nationalism, but being a devout Muslim did imply an allegiance to the newly formed nation. Still, many chose to stay. And with the imposition of a land border, they went from being colonial subjects to being stateless people: neither Moroccan nor Spanish.

When I asked Mohamed Mustafa, leader of Ceuta Ya!, the city’s newest political party, what the most important moment in the history of Ceuta’s Muslim community was, he didn’t hesitate: the struggle for Spanish nationality four decades ago.

It started when Spain moved to join the European Community. Franco died in 1975, Spain became a democracy in 1978, and by the 1980s it was entering the European fold. As a precondition for joining the European Community, it had to adopt a comprehensive immigration policy, not so much to regulate immigration as to regulate the legal condition of the foreigners already in the country.

The 1985 Immigration Law was the result — but it failed to consider the unique circumstances of the Muslims in Ceuta and Melilla. At first, it left most of them with no possibility of gaining citizenship and even facing the risk of deportation to Morocco. “You have to remember that most of that population were people that had been born in Ceuta,” said Mustafa. “Their fathers and grandfathers had fought in the African wars.”

The threat of expulsion brought the Muslim community onto the streets. Part of the non-Muslim population responded with counterprotests, demanding the law be enforced. Eventually, the national and local government came to an agreement that allowed most to gain citizenship. “It was popular and international pressure that forced them to recognize in these Ceutíes and Melillenses a status which was inherent in their birth: that of being Spanish,” said Mustafa. “But those that live in privilege felt that this emancipation went against their privilege. Rather than thinking that, at last, we have a city united with a single social body, they felt a touch of fear.”

This fear was, in part, borne of Ceuta’s geopolitical situation. Ceuta is claimed by Morocco, and this has led some to fear the growing political influence of Ceuta’s Muslims, no matter how they might assert their Spanishness. But it was also the fear of a shift in Ceuta’s social order. Now that Ceuta’s Muslim population was no longer politically excluded, it might start to question its lingering social and economic exclusion. Both fears were sharpened by the knowledge that the Muslim population was growing and would one day become the majority in the city and, perhaps, the dominant political power.

The local government reacted by adopting the concept of convivencia as Ceuta’s official heritage. From the ’80s it became a political project to maintain social peace, as well as the centerpiece of the city’s tourism campaigns, which frame Ceuta as where Europe meets Africa and where four religious cultures — Christian, Muslim, Hindu and Jewish — live in harmony.

Convivencia is a difficult thing to disagree with, but there were, and are, some dissenting voices. Mustafa argues that, by prioritizing social peace above all else, the call for convivencia also had the effect of precluding any challenge to the social order. “In the time of Franco the discourse of convivencia was absolutely self-serving,” said Mustafa. “That hasn’t changed much. The concept has been reinterpreted through the interests of the elite. Although the far right doesn’t use this discourse anymore, the status quo in Ceuta centers on it.”

At a glance, the status quo in Ceuta is not a pretty picture. Unemployment is almost 30%, double the national average. The city is deeply dependent on the public sector, which accounts for 50% of GDP and provides jobs for half the working population. Poverty, child poverty and school failure rates are among the worst in Spain.

But Mustafa says you need to disaggregate the data. “Because there are really two Ceutas: one of opulence and one of poverty,” said Mustafa. “One population that lives practically in privilege and another that lives with some of the worst social indicators to be found in any country in Europe.” I asked whether these two Ceutas corresponded to the Muslim and non-Muslim populations of the city. “Sadly, that is essentially correct,” he said.

Religion does not appear in official statistics in Spain, which makes it difficult to assess such a claim. Some would argue that only parts of the Muslim community live in such conditions. But no one would entirely refute it. Research from 2018 suggested, for example, that the poverty rate in the Muslim community was 65%, while in the non-Muslim community it was less than 15%.

This inequality is reflected in the very structure of the city. The territory itself is a kind of triangle, where the mountainous base borders Morocco and the body then narrows into an isthmus, which seems to be reaching for Spain. Relatively few Muslims live in that fine tip, where you have the oldest and wealthiest part of the city, which is known as the center. But as you move toward the border with Morocco, the neighborhoods become progressively poorer and more Muslim, in both style and populace.

The most vivid manifestation of this can be found in El Principe, a Muslim neighborhood that is next to the border with Morocco and isolated from the rest of the city. When I went there to meet Kamal, the president of the neighborhood association, he suggested a walk, so I could see it for myself. “But it’s better not to take photos,” he added. “People don’t like it.”

In recent years, El Principe has, with the media’s help, become a byword for religious extremism and drug trafficking. There was a hit TV series called “Principe” centered on these very themes. “There are lots of Ceutíes that have never come here in their life,” said Kamal. “It’s like a town apart from the city. The stigma around El Principe makes people afraid.”

Visually, the neighborhood is unlike the Castilian center of Ceuta. This is partly a reflection of a greater influence of the Moroccan style, and partly a reflection of poverty. No house is the same height, or at the same angle. No two walls are quite the same color. We cut through cool, narrow streets while Kamal pointed out paving or wiring or pipes that they had managed to get installed, always with the same comment: “We had to fight for that.”

We stopped to drink some sweet mint tea in Plaza Padre Cervós, the main square. I asked about Vox and how its discourse was seen in El Principe. “The fifth columnists thing?” Kamal said. “We know that they have a fascist discourse, and we are against that. It’s most apparent on social media. But, speaking for myself, I try not to get involved in this game. Because they feed on it. When we confront them, it gets into the media, and this is how Vox lives and grows.”

Kamal’s grandfather was a Regular. He bought a one-room house in El Principe, then went to Spain to fight in the Civil War and didn’t come back. That meant Kamal’s mother started working when she was 10 years old. She received her Spanish nationality in the ’80s. “That was when we ‘imposed’ ourselves a little,” said Kamal. “But despite winning our nationality, the right continued to marginalize us.”

“The discourse of Vox is just words, just dogs barking,” said Kamal. “The situation that the Muslim community of Ceuta is living in is the work of the current government.”

Kamal pointed out that Ceuta has received 500 million euros ($580 million) in European Funds, and yet El Principe remains in some senses a shanty town. Parts of it lack basic infrastructure, such as drinking water, streetlights and sanitation. According to the most recent population estimate (calculated in 2020) 11,000 people live there, but Kamal put the true number at 13,000. More than 95% of the houses are illegal. “And so there is an incredible kind of urban chaos, lots of overbuilding and overcrowding, with parents living on one floor, and each son living on another with his wife and children. They just keep adding floors.”

The current situation, with the dual crisis of the pandemic and the prolonged border closure, has tipped many residents into poverty. Kamal estimated that between 60% and 70% of the people in El Principe made a living from border trade, in one way or another. And many would go and do their shopping in Morocco, to save a bit of money. “The truth is we’ve had a terrible pandemic. There’s a lot of need.”

I started to mention the idea that there are two Ceutas and Kamal cut in with an arch smile: “One part lives like they’re in Europe and other like they’re in Africa, right?” He didn’t disagree, but he had heard it all before. To his mind, it’s part of the colonial heritage that endures in the city. “Maybe they won’t show it to you, coming from the outside. Maybe you won’t be able to see it all. But I live it. I feel it. It’s a reality.”

Back in February 2020, after El Foro de Ceuta, a local digital publication, obtained Islamophobic messages apparently leaked from Vox’s internal WhatsApp group, Kamal helped lead one of the biggest marches Ceuta had seen for years. They marched for convivencia. “We respect it. As far as it goes, we respect it. They’ve always sold the idea that this is a multicultural place to the outside world. And it’s true, we live alongside each other here. But each one is in their zone, as you can see.”

Mustafa was there that day, too. “There is convivencia in Ceuta, and it’s something sacred. Perhaps we don’t value the small victories in our society enough. … I suppose I am an optimist in that sense. I think Ceuta has a lot to bring to our country — a country that is still immersed in the construction of its diversity.” Then his mind snapped back to the struggle. “But convivencia can’t simply mean social peace — there must also be social justice.”