In the summer of 1947, a reporter for Qui? Detective magazine walked into a brothel on the edge of an army camp in Frejus, in southeastern France. The only thing distinguishing this building from the other boxy, ugly army barracks was the barbed wire fence around it. He took note of a cupboard full of douches and antiseptic, and posters on the wall telling soldiers how to wash out the insides of their penises with a thin tube after paying for sex. Walking into the main room, he noticed a makeshift wooden bar and a corridor that led off to the bedrooms.

In the middle of the afternoon, the 14 women who worked in the brothel were sleeping, many of them half-naked. One, wearing a swimming costume, was quietly reading a novel in one corner. They were regaining their strength before the evening shift started, when they might have to have sex with up to 20 men in just one night.

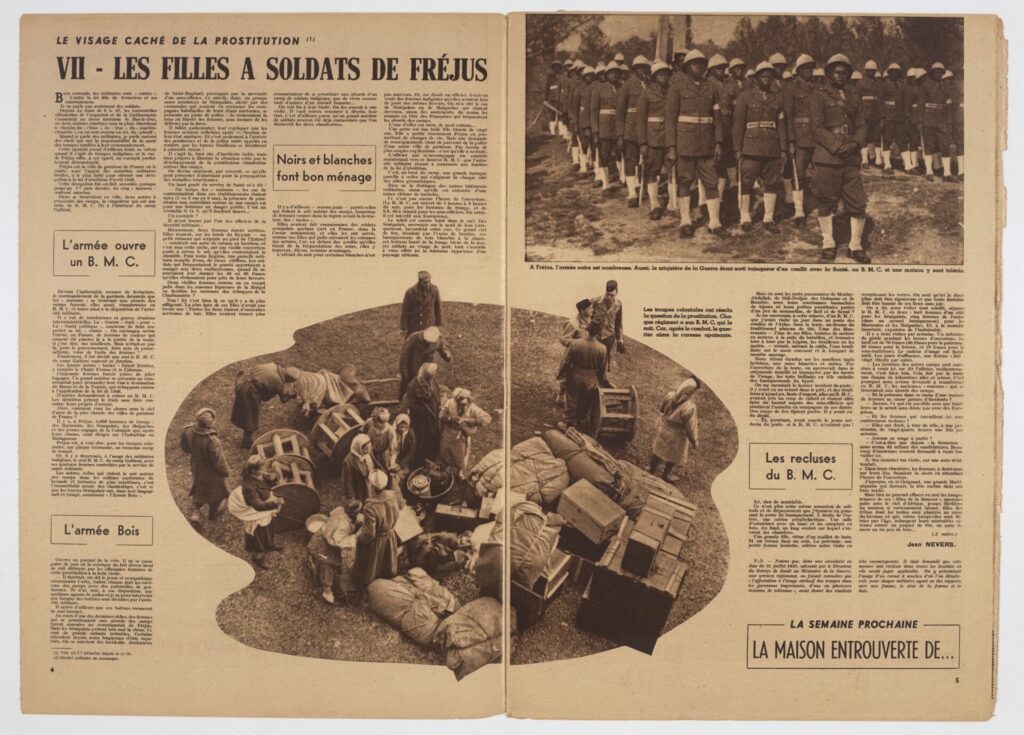

Their presence at the army camp was illegal — but not because the women themselves were performing illegal acts. The journalist who toured the brothel that day would reveal to the public that, despite the government banning brothels the year before, the French army had secretly arranged for nearly 300 women from Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia to be trafficked to France, often against their will, to work in confined military brothels, servicing North African soldiers. The army, operating on racist stereotypes about its soldiers from North Africa, set up a system of 32 “bordels militaires de campagne” (mobile military brothels, often BMCs for short), in which it kept women secluded, in almost prisonlike conditions, as a means of “protecting” the purity of French women and subduing members of its rank-and-file who had fought in World War II.

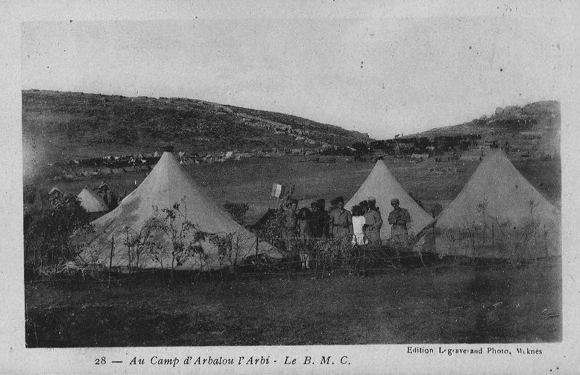

The BMC at Frejus wasn’t the first military brothel full of North African women that the reporter for Qui? Detective had seen. Years earlier, in the Atlas Mountains in Morocco, he had visited a tent in which women served soldiers trays of mint tea and much more. Tents like this moved through the countryside attached to a regiment as the French army went about their process of “pacification” of the newly acquired territory.

France is estimated to have killed 825,000 people during the 40-year “pacification” of Algeria, and 100,000 during the 20-year “pacification” of Morocco. Even more local people died during the decades of poverty, wealth extraction, massacres and war crimes that followed. At the same time, hundreds of North African women were forced to sell sex in military brothels to the French soldiers enforcing colonial rule and killing their compatriots.

The women who worked in the BMCs were recruited from local brothels in North Africa, where sex work was legal and controlled by colonial authorities. France brought this system of controlling sex work, which was called “regulationism,” to Algeria when the French army invaded in 1830. As French control spread, when Tunisia fell under French power in 1881 and Morocco in 1912, any woman who sold sex had to be registered as a “fille soumise” (the name for a woman who sold sex, literally “submissive girl”) and sent to a brothel, from which she was forbidden to leave — except for an occasional visit to the hammam. There were no weekends off, no visits to families. The brothel became their whole world.

Though many of the women in the brothels in North Africa became sex workers as an escape route from extreme poverty, others did not, in fact, choose to be there at all. The colonial police could arrest any woman in North Africa if she were merely suspected of selling sex, with no evidence required. (Some of the women who were arrested were later found to be virgins when they underwent genital examinations for signs of venereal diseases.) What loomed over these arrests was a brutal future: After a woman was arrested three times on suspicion of selling sex, the colonial police would register her as a prostitute and send her to a brothel, where she would be condemned to years of rape in the guise of selling sex. In Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco, thousands of women met this fate — often despite pleading letters for their release from husbands or fathers. They were forced to sell their bodies against their will, trapped inside brothels for years on end, where they faced physical abuse, financial exploitation and nonconsensual sex. This system of legalized sexual abuse was introduced under French rule as a “social hygiene” measure that meant women’s sexuality was constantly policed but, more pointedly, it could be used as a tool to intimidate, control and repress — if someone stepped out of line, they risked their wife or daughter being shut up in a brothel with little to no recourse. The women in French BMCs were recruited from these brothels.

The Algerian writer Germaine Aziz sold sex in North Africa and France in the 1940s and 1950s, after being tricked into joining a brothel as a teenager. In her memoir, she described how women selling sex in North Africa feared being sent to work in the military brothels. It was “the biggest fear of all the girls here, whatever their age or race,” she wrote. “These bushbirs set up in Algeria, Tunisia or Morocco, were in the desert. Guarded by the army, they served the soldiers, the troops from Africa and a few wandering Arabs. No girl ever came back, but some men, some old madams spoke about it. Anything was better than this prison.”

When World War I began and North African soldiers came to fight on French soil, the brothels came too. They were established in major camps to maintain “French prestige,” reflecting a widespread fear that colonial racial hierarchies could be drawn into question if North African men were able to have sex with white women — particularly if the women were the ones pursuing relationships. One army report explained that “to maintain France’s prestige in the eyes of the natives and of the world it seems vital, in fact, to avoid as much as possible that they have relations with French women, even prostitutes.” This was considered particularly necessary because, as one French captain wrote, when the soldiers return to North Africa “where access to European establishments is forbidden to him, he would be able to boast about having relations with French women.”

At least 141 Moroccan and Algerian women were trafficked to Naples for sex work between March 1943 and April 1944. But this still wasn’t enough for the French army. In April 1944, they telegrammed to Algeria and Morocco to recruit a further 150 Algerian women and 300 Moroccan women. These hundreds of North African women traveled alongside the colonial troops in Europe during World War II.

One unlikely witness to this was Winston Churchill’s cousin, Anita Leslie, who drove ambulances for the Free French army. In her 1948 memoir, she recalled seeing a group of Moroccan women getting on an American ship in Italy. “Classed as army personnel, they were attired in American soldier’s trousers,” she wrote, in sharp contrast to their traditional Amazigh face tattoos, veils and scarves from the Italian markets. But Leslie also saw with her own eyes the dark side of these brothels. She described seeing a very young Moroccan girl being kicked and screamed at by army officers. Years later, she could still remember her “blue, bewildered eyes, like those of a frightened cattle on fair day. She had probably been sold, at the age of 12, to the military bordel of her tribe.”

In April 1946, France passed the Marthe Richard law. Named for the woman who had championed it, a councilor for the 4th arrondissement in Paris who was also a former sex worker and World War I spy, the law closed some 1,400 brothels that had been operating illegally in France, after more than a century of sex work operating aboveboard.

Turning off the tap of legal sex work posed a problem for the French army: Though colonial soldiers from North Africa were supposed to have been demobilized and returned home by July 1, 1946, a shortage of boats meant that some 30,000 North African troops were still in mainland France in the summer of 1947. They lived in squalid conditions, so bad that some even said their lives had been better when they were in German prisoner-of-war camps.

According to Lt. Col. Palange, one of the commanding officers for the Moroccan troops, it was “unrealistic” to expect North African troops to go for months without sex. Racist colonial ideas about the sex drives of North African men led to renewed fears about the safety — or “purity” — of French women in the surrounding areas if sex could not easily be bought. He concluded that “developing the BMCs is, in my opinion, the best way to mitigate rapes or attempted rapes that could take place in this country.”

The army, knowing they were breaking the law, tried to keep the brothels a secret. In a confidential memo organizing the whole scheme, one French general explained that these BMCs for North African soldiers were an “infringement” of the ban on brothels in France. He made it clear that, for this reason, the army’s project would need to “be carried out with the utmost discretion and not be discussed outside of any military spaces responsible for recruiting staff.” The only people who were supposed to know about it were the army officials recruiting women from brothels in North African cities and the “patronnes” — the madams — to be in charge of them.

The brothel madams were recruited and selected by the French army, and ruled the BMCs with an iron fist. They were often violent to the women there and handed down harsh fines if the women did not follow the brothels’ extensive rules exactly. The women were not allowed outside the brothels and were constantly guarded. All contact with French people was forbidden. If the women wanted to send letters or buy groceries or any other necessities, they had to make purchases through an army officer, who often charged an extra fee.

The women were also forced to undergo three “health visits” a week. These were genital examinations to look for sexually transmitted diseases (most often for syphilis). They involved a speculum and were incredibly uncomfortable, intrusive and often dehumanizing. The doctors who carried them out rarely respected the women, so didn’t bother making sure that they were comfortable. These doctors were trained by medical pamphlets that told them that almost all Moroccan women were suffering from syphilis but trying to hide it, which meant that they treated the women in the brothels with suspicion and assumed they were lying if they claimed to be healthy. Condoms were rare. Large cupboards inside the brothels were full of antiseptics with which the women were supposed to douche themselves after sex. These included potassium permanganate, which burned the skin and stained it purple. The men were supposed to “irrigate” their penises with this liquid, but very few did because of how uncomfortable it was — and because nobody wanted a purple penis.

The BMCs were completely “forbidden to Europeans,” according to the magazine article and secret army communiques. Every night, from 5-9 p.m., the brothels were open to the troops; from 9:30 on, it was the officers’ turn. Soldiers traveled from camps miles away to make use of the brothels. Busy evenings could easily mean 20 clients for each woman. Each man paid the brothel less than a dollar (70 francs, worth around $14 today) to have sex with one of the women there. After the madam and her assistant had taken their cuts, the women were left with less than half of that.

The French army itself also took a cut: The women were provided with wooden barracks to live and work in, but they had to pay the army for their own food, fuel and electricity. They also had to cook their own meals and were forced to eat separately from the soldiers who shared the camp, to make sure they did not develop any relationships that were not strictly transactional.

Despite their efforts, the French army was unable to keep the BMCs secret. The article in Qui? Detective was a major blow. Even though the reporter did not realize the scale of the operation, thinking that there was only one army brothel in France instead of the 32 that had been organized, he was quick to criticize the hypocrisy of the French army. After the journalist saw the BMC, all he could think about was what he had seen years earlier in the military brothel in Morocco: Indigenous Amazigh women with traditional chin tattoos “who, even though they were bent over with age, swapped their poor caresses for just a pack of tea, a stick of sugar, or a bit of wood.” The memories of their poor living conditions and poverty had haunted him for years. After walking through the camp in Frejus, talking to the madam and seeing the living conditions of the women in the brothel in France, the parallels were clear.

While other nations with dark histories of forced sex work for the military — notably Japan’s forced prostitution of Korean “comfort women” — have, in recent decades, recognized and even apologized for their roles in such exploitation and abuse, France has never acknowledged these illegal brothels or the impact they had on the hundreds of North African women who lived and worked there — some against their will.

As the journalist who saw the camp wrote in 1947, this was clearly, “for the government, an act of pimping or even human trafficking.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.