The Suez crisis of 1956 has often been presented as the last burst of British imperialism in the Middle East.

But subsequent wars have given plenty of reasons to question that.

The end of the empire is a notion that I began to challenge 30 years ago as a doctoral student, and events at the time seemed to bear my argument out: I was completing my thesis as British forces joined an American-led coalition to liberate Kuwait from Iraq.

The way Britain’s role in the Middle East is usually framed has continued to nag at me throughout my career as a historian — not least because of the accumulating evidence. Prime Minister Tony Blair’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan provided the clearest demonstration that Britain had never really withdrawn from east of the Suez or abandoned its role in the Middle East. Most fascinating of all was the way that Blair’s framing of the wars as an existential struggle for the preservation of Western civilization mirrored the warnings delivered by another British prime minister, Anthony Eden, over Suez half a century earlier.

In “False Prophets,” I set out to connect Eden and Blair by looking at the continuing fascination successive occupants of 10 Downing Street have had for the Middle East. British prime ministers have tended to be false prophets, conjuring existential threats to the Western way of life out of the sands of the Middle East.

In 1956, Britain connived with France and Israel in an attack on Egypt, supposedly to ensure free passage through the Suez Canal, but with the intention of overthrowing the country’s president, Gamal Abdel Nasser. In many ways, it was the most extraordinary of plots. For a start, the conspirators detested each other. When Selwyn Lloyd, the British foreign secretary, met the Israelis in secret to consider the scheme, they complained that he behaved as though he had a foul smell under his nose. But the overriding imperative of defeating a common enemy in Nasser eventually overcame their distaste, and they pressed ahead.

An even stranger twist of Suez lay in the unraveling of the military plan rather than its formulation. The Suez operation was halted, with British forces already fighting their way up the canal on Nov. 6, 1956, because of economic and political pressure from the United States, Britain’s closest ally. But, as recently released sources regarding intelligence exchanges between Britain and the U.S. reveal, this U.S. opposition was the oddest twist of all. Odd because a top-secret, British-American intelligence working group meeting in Washington at the beginning of October had already agreed on the central British goal of overthrowing the Egyptian leader. The only remaining differences between Britain and the U.S. were over timing and method. Should they pursue a strategy of economic and political warfare designed to topple Nasser as the Americans preferred, or would they instead opt for a military coup as the British wanted?

It was the timing of Britain’s military action — just before the U.S. presidential election — as much as the method Britain had chosen that resulted in the spectacular breakdown of British-American relations. That was clear from an infamous remark from Secretary of State John Foster Dulles to the British foreign secretary on Nov. 17, 1956: “Why did you stop?” he asked. “Why didn’t you go through with it and get Nasser down?” If only the British had toppled Nasser quickly, and without interfering in the U.S. presidential election timetable, there would have been no British-American breakdown over Suez.

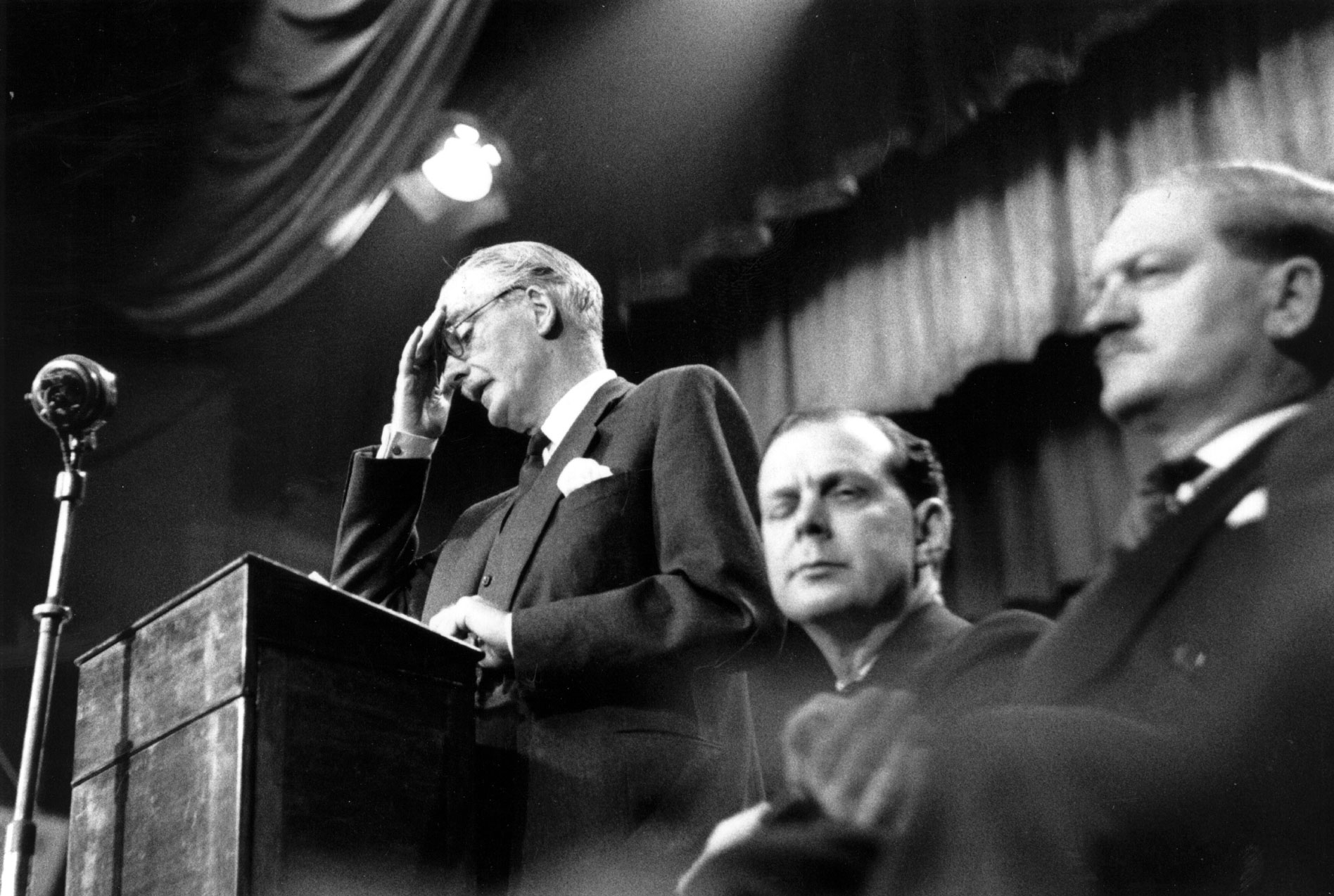

A further irony of the aftermath of Suez was that it brought to office a new British prime minister in the shape of Harold Macmillan, who was far more hawkish over the Middle East than his predecessor, Eden. In the summer of 1957, the British intelligence services once again collaborated with the Americans, this time in framing what was known as the “Preferred Plan” for toppling the anti-Western regime in Syria. The plan — concocted once again by a secret British-American intelligence working group — envisaged a series of provocations on Syria’s borders with Jordan and Iraq, leading to a “tribal rebellion” and a coup. Extraordinarily, the scheme also included the targeted assassination of three key Syrian officials. For Macmillan, the plan was a “formidable document,” and he pressed for its implementation, only to have the ground cut from under him when the political situation in Syria was transformed by intervention on the part of Nasser. His landing of Egyptian troops at the port city of Latakia defused the political crisis in Syria, forcing the “Preferred Plan” to be abandoned.

Macmillan’s penchant for covert action and secret maneuvering over the Middle East was shared by his successors in office. Alec Douglas-Home engaged in a secret war in Yemen in 1963-64, attempting to undermine the pro-Nasser republican regime, which had come to power in 1962, by the covert supply of arms and money to the opposition royalist forces. This was coupled with a campaign of black propaganda and sabotage operations designed to undermine the republican regime’s morale.

When a Labour government replaced that of Douglas-Home in 1964, Prime Minister Harold Wilson and Foreign Secretary George Brown both maintained covert back channels, which they used to influence the combatants in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Brown acted as a covert intermediary between King Hussein of Jordan and Israeli leaders, writing conspiratorially to the king that “I think you should know I am still being used as a post-box. Letters these days are bad. Too many people read them.” Brown believed passionately that peace was still possible after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war: “I am for helping,” he informed the king. “I reckon there is still a chance, and you and I together can handle the rest of the world!”

Meanwhile, Wilson used his adviser, Gerald Kaufman, as a covert back channel to the Israelis. “He would send me every day to get a report from the Israeli ambassador, Aharon Remez, and I would in turn report back to the British intelligence,” Kaufman admitted years later. The Israelis, for their part, used this back channel to influence the British government’s policy, blocking a plan to create a personal bodyguard for Hussein under the leadership of former SAS (British elite special forces) officer Col. David Stirling.

Under Wilson’s successor as prime minister, Edward Heath, an intelligence officer stationed in Jordan named Bill Speares played the most important covert British role. Not only did Speares install and run the king’s only means of secure communications with the outside world during the “Black September” crisis of 1970, but he was also at the heart of the king’s response during the Arab-Israeli war in October 1973. A radio communications link that Speares installed gave Heath’s government privileged access to information about the king’s plans during the 1970 crisis, when he unleashed his army against the Palestinian guerrillas based in Jordan and against the Syrian forces that invaded the north of the country.

When the Arab-Israeli war broke out in 1973, Hussein was wary of becoming involved but came under increasing pressure to do so. Syria asked him to send troops to cover its flank in the Golan Heights, but the king was worried about Israel’s likely reaction. He had no intention of using them to attack Israel from the Golan and wanted the Israelis to know. He was struggling, though, to give a reason for the military maneuvers that the Israelis would believe. Speares solved the problem by drafting a message from the king to be relayed to Israel via British channels. It presented the movement of forces in terms of the king’s fears about a potential coup in Damascus, which could result in a Syrian threat to Jordan (as had been the case in 1970). In the event, the Israelis tolerated the king’s move and avoided targeting his forces in the Golan.

When Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait in August 1990, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher played a leading role in confronting Saddam Hussein, but it ended abruptly with her fall from office the following November.

Recently released documents show that Thatcher’s uncompromising stand even extended to privately advocating the retaliatory use of chemical weapons against Iraqi forces occupying Kuwait. Thatcher repeatedly pressed the U.S. administration of President George H.W. Bush to be ready to retaliate with chemical weapons in response to any Iraqi use. The normally hawkish defense secretary, Dick Cheney, must have been astonished to find himself significantly out-hawked on this issue by Thatcher, who berated him that “if we wished to deter a CW attack … we must have CW weapons available.” The Americans were astonished by Thatcher’s position, with Cheney warning that “the president had a particular aversion to chemical weapons.” But Thatcher remained undeterred: “It would be justified for the United States to use CW against Iraqi armoured formations in Kuwait if the Iraqis used it first,” she insisted. Thatcher, who was nicknamed “The Iron Lady” for her staunch anti-communist stance during the Cold War, had apparently morphed during the Gulf Crisis into “Chemical Maggie.”

The chief custodian of Saddam’s chemical and biological weapons’ programs was his own son-in-law, Gen. Hussein Kamel al-Majid, the third-most powerful man in Iraq after Saddam and his bloodthirsty son, Uday. In August 1995, after a falling-out with Uday, which left him in fear of his life, Kamel unexpectedly fled to neighboring Jordan, where he was offered sanctuary by Hussein. He proceeded to divulge in detail Saddam’s weapons of mass destruction programs. But the message he brought was deeply unexpected. Saddam had destroyed all his WMD stocks after the Gulf War and was resisting international inspections only to preserve the illusion of strength.

Kamel’s claims were dynamite and unwelcome to both the British and American intelligence services, who were also dismayed by his attempt to set himself up as a figurehead for the Iraqi opposition. Indeed, the reaction of both MI6 (Britain’s foreign intelligence service) and the CIA was so negative that Hussein evidently took offense at the treatment of his guest. Personal letters from David Spedding, the head of MI6, and John Major, Thatcher’s successor as prime minister, were needed to mollify him. But eight years before the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, which took place on the pretext of dismantling Saddam’s WMD programs, Kamel’s claims turned out to be wholly accurate. Given that Kamel had overseen these WMD programs, it seems extraordinary that more credence was not given to the information he presented at the time.

The controversy created by the invasion of Iraq in 2003 has been helpful in opening new sources of information because it spawned a series of inquiries culminating in the Chilcot inquiry into the Blair government’s decision making over the war. But it remains the case that a culture of secrecy pervades the corridors of the British government in Whitehall. While writing “False Prophets,” I found myself on a collision course with this culture when I submitted a Freedom of Information request for the release of documents from the Prime Minister’s Office covering Britain’s relations with the regime of Moammar Gadhafi of Libya, from the bombing of a Pan Am airliner over the town of Lockerbie, Scotland, in December 1988, to the fall of Gadhafi during the Arab Spring in 2011.

For reasons that remain unclear, the declassification of documents covering Britain’s relations with Libya has lagged behind the release of official documents on Britain’s relations with other countries in the Middle East, such as Iraq, Syria and Egypt. The Cabinet Office, which was responsible for reviewing these documents, fought my freedom of information request tooth and nail for five years until I finally won in court in 2018. The documents they were compelled to release showed that economic considerations, especially in the form of bilateral trade, were pivotal in the Blair government’s decision to restore diplomatic relations with Libya in 1999 and to pursue a detente with the Gadhafi regime thereafter. According to Blair himself, “We should not be too cautious in expanding our commercial relations with Libya.”

But perhaps even more important, this victory in court prevented the further erosion of freedom of information rights that are essential for both historians and journalists in chronicling the troubled history of British and broader Western involvement in the Middle East. The court judgment in my favor recorded: “‘These are all substantial questions of public policy where there is a profound public interest in understanding the government’s approach. The information sought is of great value to the public and to a historian.”

The debacle of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, with which “False Prophets” concludes, shows that the British role in the Middle East always went hand in hand with its relationship with the U.S. Correspondingly, there is much to be learned about the controversial history of U.S. involvement in the region from British sources. Ultimately, though, both British and American intervention in the region across the seven decades since the Suez crisis has done much more to harm Western security than to reinforce it.