The evidence for Vladimir Putin’s apparent intent on reinvading Ukraine is familiar enough, not least because it has been trumpeted by top officials in Washington and London over recent weeks with unusual and increasing emphasis. Some 170,000 Russian troops have been building up on Ukraine’s borders since October. According to U.S. intelligence sources, those troops’ commanders have been given orders to prepare detailed tactical plans for a land invasion. Russian agents have been preparing attacks and provocations on the ground inside Ukraine, and last week the U.K. government accused Moscow of plotting a coup against Kyiv’s government and lining up a group of pro-Kremlin, Ukrainian politicians to take over. Supplies and reinforcements have reportedly been sent to Russian-backed separatists in the breakaway eastern Ukrainian regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. Last summer Putin published an essay casting doubt on Ukraine’s validity as an independent country. He’s also on the record as saying that Ukraine’s move toward NATO is an existential threat to Russia’s national security.

On the face of it, it’s no wonder that Western capitals are buzzing with talk of war, nor that NATO countries have stepped up supplies of “defensive” weaponry to the Ukrainians. The U.S., British and Australian embassies have even ordered the evacuation of staffers’ families from Kyiv. And though Putin has not threatened an invasion — indeed, he has repeatedly denied that he has any intention of any such thing — Western leaders insist that war is not just likely but imminent.

And yet there’s one significant disconnect in this picture: There’s no talk of imminent invasion plans in Moscow, not on state media, not among political journalists, not among the political class. Even the Ukrainians themselves, supposedly in the firing line, don’t seem worried. “These risks have existed for more than a year. They haven’t become bigger,” Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelenskiy said last week. Ukrainian government spokesman Oleh Nikolenko called the evacuation of Western embassies “premature and overly cautious.”

Russia’s state-controlled media isn’t making any efforts to prepare the population for war — and that’s the crucial point. The state’s media message — tightly regulated by the Kremlin in weekly meetings with top news outlet chiefs — is of dialing back NATO expansion and preventing NATO from positioning its missiles along Russia’s long, soft border with Ukraine. In other words, exactly the party line that Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has been pushing in ongoing (and so far fruitless) talks with the U.S. in Geneva. Unlike the buildup to Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, there’s no barrage of reports of a “genocide” against the Russian-speaking population of Ukraine. And while there’s still plenty of mockery and bitter criticism of Kyiv’s current leadership for being Western puppets, there is no talk of the regime being “fascist-controlled” — a key talking point in 2014 as the Kremlin attempted to present the war in Donbas as a modern replay of the struggle against Hitler.

That lack of domestic messaging is a vital bellwether to the Kremlin’s true intentions — and a vital piece of evidence that Putin’s heavy metal posturing is aimed solely at foreign audiences from Kyiv to Washington, not for a domestic one.

Polling shows clearly that a land war against Ukraine would require some very hard selling to get the Russian people behind it. A poll last month by the independent Levada Center in Moscow showed that 66% of Russians aged between 18 and 24 – the young people that would have to actually fight a war – have a “positive” or “very positive” attitude toward Ukraine. That’s despite a backdrop of unceasing vitriol directed toward Ukraine on state television. After his annexation of Crimea in 2014, Putin’s ratings indeed soared. But taking over a near-island with a population that is over 90% Russian-speaking is a very different prospect than an invasion of Ukraine itself — and the reason that Putin never officially sent troops into Donbas and has consistently insisted that the breakaway region should remain part of Ukraine, albeit with special status. Last week the opposition Communists proposed a debate in the Duma on recognizing the republics’ independence. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov poured cold water on the idea, warning that “it’s very important to avoid any steps that could provoke an increase in tensions.” So for the moment at least the Kremlin is sticking to its strategy of keeping the breakaway republics inside Ukraine.

“Russian conformists are, of course, traditionally bellicose people, but theirs is the bellicosity of propaganda television talk shows, or the language of online hate,” argues Andrei Kolesnikov of Moscow’s Carnegie Center. “No conformists want a large-scale war: conscription is not part of the social contract, particularly at a time of accelerating inflation and economic stagnation. … The average Russian is tired of self-deception and of persuading themselves that if a war does happen, it will not impact their lives or those of family members.”

The polls also show another, more worrying dynamic for Putin — in December, the number of Russians ready to vote for his reelection stood at 32%, a record low.

The traditional narrative is that a failing politician needs a “short, victorious war” to restore their popularity. But the logic is double edged — the key word is “victorious.” The phrase was coined by Prime Minister Vyacheslav Plehve in 1904 as a reason to enter the ultimately disastrous Russo-Japanese war. But while Russia’s numerically and technically superior military would have no problem rolling over Ukraine’s defenses, there is serious doubt as to whether Putin could capture and hold more Ukrainian territory. Such an occupation would almost certainly be open-ended and unwinnable.

A less risky invasion scenario – suggested by analysts such as Robert Lee of Philadephia’s Foreign Policy Research Institute – would be a more limited raid that would show the weakness of Ukraine’s military and demonstrate NATO’s powerlessness to help.

But while such an in-and-out raid would be more militarily achievable and avoid a bloody quagmire, the wide-ranging and “unprecedented” sanctions threatened by U.S. President Joe Biden would still leave Russia’s economy devastated. So far, sanctions have not hit Russia’s most vital economic wellspring – its natural gas supplies to Europe, about to be augmented by the long-delayed opening of the Nord Stream-2 pipeline. Even a limited invasion of Ukraine would finally bounce Europe into seriously rethinking its dependence on Gazprom – in the process canceling Putin’s one strategic advantage over the EU. It would also hit him at his most vulnerable domestic point: the plunging living standards that are already seriously eroding his popularity.

So if Putin can’t win a war in Ukraine, faces crippling economic consequences if he tries, and is doing nothing to prepare his people to fight one, what is he doing?

The simplest answer is that he appears to calculate that bluffing about war might win him some concessions from Washington and NATO. Actual war, by contrast, will not.

From the very start of the crisis Putin has been very careful to insist that none of his current military maneuvers have any hostile intent. He has not threatened Kyiv or made any demands. He has not even publicly complained about the treatment of ethnic Russians in Ukraine — the casus belli that triggered the 2014 war. Instead, he has vocally and repeatedly beat the drum all Russian leaders have been beating since the fall of the Soviet Union — that NATO expansion up to Russia’s borders is unacceptable. The aims of Putin’s phony war are very clear: He wants an end to NATO’s engagement in Ukraine.

Does Putin need to fight an actual war to achieve that end? As yet, he doesn’t have to. Ukraine is not about to join NATO. Indeed, under current rules it cannot join NATO because it has unresolved border disputes in Crimea, Donbas and Transdnistr dating back to 1994. There’s already been considerable pushback from some of Washington’s European partners about further engagement with a country that has no legal chance of ever joining. And that’s the point of Putin’s pugnacious diplomacy — to sow enough dissent in NATO ranks about the wisdom of its Ukraine policy and to make it very clear that more military help to Ukraine could, in the future, lead to war. In a word, Putin’s showing the world that he’s serious.

The contrary argument is that Putin believes that now is the time to take his chance, decapitate the government of Ukraine with a quick strike into Kyiv on the pretext of some concocted provocation and set up a puppet state. That certainly seems to be the message of an unprecedentedly detailed U.K. government statement issued last week that openly accused the Kremlin of planning a coup and named four former Ukrainian ministers in pro-Russian Viktor Yanukovych’s government of being Moscow’s candidates for leadership of such a quisling state.

Is it possible that some people in Russia’s military and intelligence services have cooked up such a plan and sounded out potential candidates? Absolutely. It’s also highly plausible that Russia has many undercover officers and agents exploring ways to foment ethnic unrest and organize provocations against the Russian-speaking population of central and eastern Ukraine. But does that add up to a serious coup plan? Hardly.

Former Ukrainian MP Yevhen Murayev, named by the British as the Kremlin’s puppet candidate for Ukraine’s presidency, lost his seat when his party failed to win 5% of the vote in the 2019 elections. And despite being the owner of the “Nash” TV station — which Ukrainian regulators have been seeking to shut down since last year for airing pro-Russian propaganda — he’s actually banned from Russia, where prosecutors have frozen the assets of a firm belonging to his father. The other four men named by London as key plotters — former Prime Minister Mykola Azarov, former deputy secretary of the Ukrainian National Security and Defense Council Volodymyr Sivkovich, ex-parliamentarians Sergiy Arbuzov and Andriy Kluyev — have, by contrast, been exiles in Russia since 2014. The idea of these discredited has-beens forming a credible Russian-backed government in Kyiv is risible.

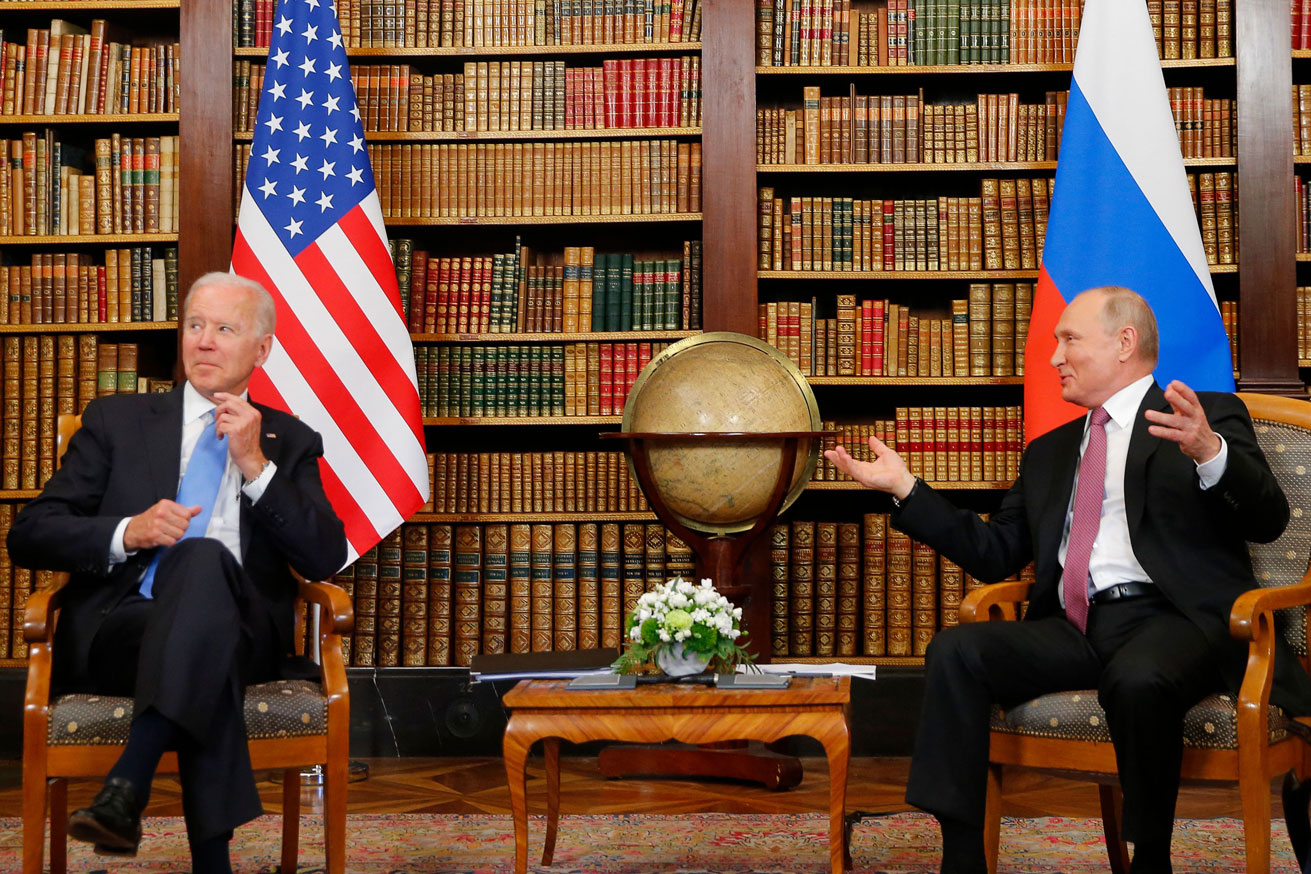

The next question is why the West is apparently taking the threat of invasion so seriously. The answer is equally simple: Talk is cheap. Biden and U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson have both threatened dire consequences for Putin if he invades. If he doesn’t, they can claim the political credit for facing down a dangerous aggressor. But note one crucial detail: No Western leader, including Biden, has ever promised to put NATO boots on the ground to protect Ukraine, only materiel and economic sanctions have been promised.

But in one sense, Putin has already made his point by exposing cracks in NATO unity — and by bringing Russia to the forefront of Washington’s global strategy. Back in 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron claimed that waning American interest in Europe was making NATO “brain dead.” Biden’s policies also showed that Europe was an afterthought — from a strategic pivot toward China to the Afghanistan withdrawal, to supplanting France as a supplier of submarines to the Australians. It’s no accident that Putin has pursued direct talks with the Americans over Ukraine, conducted over the heads of Europeans. As Elbridge Colby — the architect of the 2018 National Defense Strategy, dominated heavily by China — put it recently, the U.S. “won’t have a military big enough to increase commitments in Europe and have a chance of restoring [U.S.] edge in Asia against China.” Therefore, it’s Washington that has to be convinced that deeper engagement with Ukraine is a dangerous distraction from their true strategic goals.

Meanwhile, Germany has refused to supply weapons to Kyiv. German naval chief Kay-Achim Schoenbach argued earlier this month that it was “easy to give [Putin] the respect he wants, and probably deserves as well” — and called reports of Russian plans to invade Ukraine “inept.” Though Schoenbach soon resigned, his comments betray a deep division between many political and military leaders in Germany and France, who are nervous about further NATO expansion and the Eastern Europeans who have been most vocal in stepping up support for Kyiv’s eventual accession.

Russian Sen. Oleg Morozov, who until his retirement last year was a key member of Putin’s inner circle, gave crucial insight into the Kremlin’s hopes for its talks with Washington. “The [Americans] could have said no a long time ago,” Morozov told Rossiya One on Jan. 21. “There was nothing hindering them from saying, ‘listen, none of your proposals is acceptable to us, not one of them is possible, goodbye, the talks are over.’ I, as a person who has been involved in talks of this level many times, take this to mean that negotiations are ongoing.” Offering a piece of “insider information,” Morozov observed that “there is a part of these talks which does not appear in the public sphere: ‘Let’s agree on this publicly, but about this other thing we’ll agree on not publicly.’ We’ll clench our fists and we’ll fulfil those agreements. And I believe that inside that clenched fist could be the very point that scares everyone so much — Ukraine and NATO.”

In other words, the Kremlin security establishment’s plan is to convince Biden that they’re serious about their Ukrainian red line. And that they are not expecting a public repudiation of Ukraine by Washington, which would be politically impossible. Much less, a yes to the Kremlin’s absurd demand that NATO agree not to deploy troops in member states that are close to Russia’s borders. Rather, the hope is that an understanding can be reached, a point made, that Ukraine will be a bridge too far.

Clearly, there are dangers in Putin’s plan. When Putin took Crimea in 2014, he lost Ukraine. By removing 13 million pro-Moscow voters, plus 2 million more in Donbas, he skewed the hitherto finely balanced East-West seesaw of Ukrainian elections permanently to the West. It was Putin who ensured that there will never again be a pro-Moscow government in Kyiv — and in the ensuing war he did more to cement Ukraine’s sense of nationhood than any post-independence Ukrainian politician ever had. The same danger applies today — that threatening Ukraine only strengthens its resolve to join NATO. But Putin’s correct assumption is that it’s not Ukraine but Washington that calls the shots on NATO expansion — and his key aim is to signal that as a potentially catastrophic mistake.

The vital question is what Putin will do if none of his demands are met and the confrontation rumbles on without any compromise that would allow him to de-escalate without losing face. So far, just moving troops and tanks have succeeded in exposing NATO’s disunity, won him summits with Biden and the EU and forced the West to take Russia seriously. But if, at the end of a long road of talks, threats and cajoling, the West remains insistent that Ukraine must be taken into the NATO fold, will Putin attack? It’s possible. But to do that he would have to be willing to crash his own economy and risk his own position. To do that, Putin would have to be desperate. But for the moment, Putin’s very far from desperate – he’s riding high.