There’s a scene in Netflix’s “Adolescence” in which a bewildered father pulls away from his son. It’s a small but telling moment that says everything about the disconnection at the heart of today’s masculinity crisis.

Police have just finished questioning 13-year-old Jamie Miller in connection with the fatal stabbing of a female classmate. Now it’s just Jamie and his father, Eddie, sitting alone in the interview room. Looking tiny and scared and far too young to have committed such a terrifying crime, Jamie leans in for a reassuring hug. Instead, Eddie recoils.

“What have you done?” he rasps. “Why?”

That flinch speaks volumes. Eddie doesn’t understand his son — or, worse, he is ashamed and feels complicit. Whatever drives him, it gets to the confusion many people seem to feel right now toward a generation of boys and young men.

It’s also leaving us with a lot of questions, such as: What’s up with young men today — especially around rising incidents of violence? The creators of “Adolescence” cite as inspiration an epidemic of knife attacks committed by teenage boys in the U.K. Here in the U.S., we’ve seen a spike in political violence — including the recent assassinations of Charlie Kirk and UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson — of a kind not witnessed since the 1960s. Each act was perpetrated by a deeply isolated man in his 20s.

It’s against this backdrop that Netflix released “Adolescence” last spring. It clearly struck a nerve. The show amassed over 142 million views, making it the streamer’s second most popular English-language hit — surpassing even “Stranger Things 4.” Some of this can be chalked up to its technical bravado: Each episode was filmed in one unbroken shot, keeping the viewer rooted in long, uncomfortable, highly dramatic scenes.

But I suspect “Adolescence” also went viral because Americans are searching for answers. The last few months alone have been crowded with TV news reports, including CBS’ “Boys to Men: Why America’s Sons Are Struggling” and Michael Smerconish’s “The Male Dilemma: Social Shifts and Their Impact on Young Men” on his CNN show. Then there are books like Scott Galloway’s “Notes on Being a Man,” which instantly climbed to Amazon’s top book slot and has led to Galloway’s ubiquitous appearances across TV, podcasts and social media.

It’s clear that something is up with boys and young men. But we’re not sure precisely whose fault it is — or why it is even happening.

I suspect these are questions “Adolescence” would like to answer. The show is a marvel of artistic achievement and outstanding performances, yet I couldn’t help feeling that it emits more heat than light. It brings us into the head of one young boy who’s been shaped, even radicalized, by a steady diet of incel culture — one that fosters online misogyny and normalizes violence against girls and women. But we’re no closer to understanding what could possibly attract boys like Jamie to this subculture in the first place. Instead, the show takes great pains to detail the impact his violence has on those around him — his classmates, the police and especially his family (though, curiously, not the victim’s family).

One exception to this failure to offer much in the way of insight is a revelatory encounter, in the third episode, between Jamie and a court-appointed child psychologist. (She is, not incidentally, a woman). Unfolding over an hour — at times, agonizingly — Jamie’s introspection is by turns funny, disarming, vulnerable and abrasive. But as the psychologist asks more questions, especially about Jamie’s masculinity and sense of self-worth, he falters and tries to turn the tables. He glowers. He fires back contemptuously.

It’s here that “Adolescence” succeeds most, showcasing a fragile masculinity that, spurred on by toxic male influencers, turns believably from rage to violence. It’s a transformation that actor Owen Cooper as Jamie Miller captures in an astonishing performance.

In the end, though, that continuous one-shot — which gives “Adolescence” a compelling, claustrophobic edge — is also a good metaphor for the show’s limitations. With so much left outside the frame, we are left wondering: Why is Jamie like this? Why are boys like him giving in to rage and despair? Especially when it seems like, by many measures, their lives should be going well.

To begin to answer that, it’s worth situating “Adolescence” within larger anxieties about men and masculine identity — fears which, it turns out, are nothing new. Indeed, these cultural anxieties have bubbled to the surface in the U.S. since at least the Industrial Revolution. As far back as the 1830s, Washington Irving, the American author of classics such as “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” worried that sending young men to Europe was making them “luxurious and effeminate.”

Over a century later, historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. struck a similar note, lamenting in the magazine Esquire that postwar affluence and conformity had softened American men. “The male role,” he wrote in 1958, “has plainly lost its rugged clarity of outline.” It’s easy to see similar fears animating the “mythopoetic men’s movement” of the 1980s and 1990s, with bestsellers like Robert Bly’s “Iron John” arguing that men needed to get in touch with their inner “wild man.”

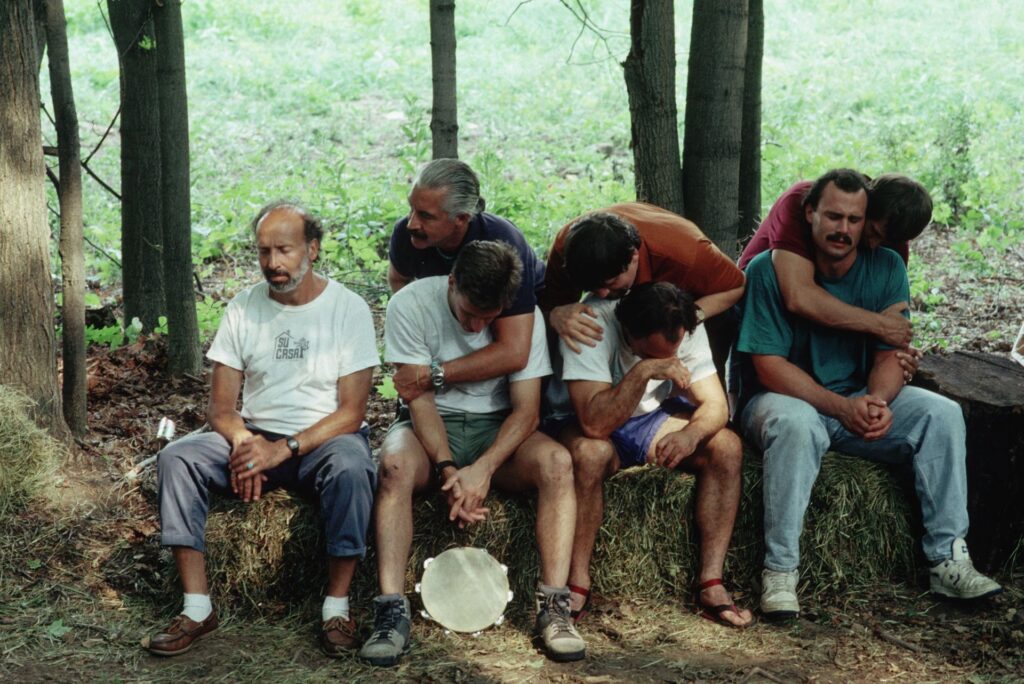

While the movement itself was relatively small — no more than 100,000 men had participated in its various events by the mid-1990s — it nonetheless made a significant impact on American culture thanks to journalist Bill Moyers’ masterful 1990 documentary, “A Gathering of Men,” which aired on American public television.

I’ve always thought Bly identified a genuine spiritual malaise in late 20th-century American men. Yet with his penchant for poetry recitals, his lute-playing and touchy-feely forest retreats, what he offered was too esoteric and too easy to mock, in particular by the mainstream press — suggesting fears about lost virility are easily provoked, no matter how much we claim to want men to get in touch with their emotions.

But Bly would also recognize Eddie’s ambivalence toward Jamie. Some of the best parts of “Iron John” explore the psychic wounds that afflicted a post-Vietnam generation of men with lost or absent fathers. In fact, if there’s a unifying theme across more than two centuries of masculinity crises, it’s exactly this loss of male mentoring.

For today’s boys and young men, the flavor of this loss is highly distinct. “Boys in the Digital Wild,” a new study of over 1,000 American boys, aged 11 to 17, revealed that this gap has been increasingly filled by online influencers, some of whom exhibit the type of misogyny and male fragility at the heart of “Adolescence.”

The study, by Common Sense Media, found that over two-thirds of those interviewed regularly encountered messages like “girls use their looks to get what they want,” or even “boys are treated unfairly compared to girls.” Meanwhile, the more of this content they consumed, the worse they reported feeling. Those in the highest-exposure group — 1 in 5 boys — were almost three times as likely to report low self-esteem and much more likely to say that sharing emotions makes them look weak.

The worst part? Boys don’t even have to go out of their way to seek out sexist content; rather, it finds them. Sixty-eight percent of the boys said misogynistic content “just showed up” on their social media feeds. Today, a majority of boys online regularly encounter a steady diet of content that harms their self-esteem or distorts their perceptions of women and girls — algorithmically peddled to them by the world’s richest tech companies.

In other words, they’re locked into what Galloway, an entrepreneur and marketing guru, calls the “largest rage machine in history.”

If the older versions of a crisis among men were stoked by fears that they were growing soft, today’s debate is supercharged by anxieties that they are not just falling behind but disappearing.

That’s because, since the early 2000s, statistics show significant percentages of boys and men losing their way — and their identities. The traditional masculine model that derived its meaning from physical labor and the role of breadwinner is today increasingly irrelevant. Deindustrialization, automation and the specter of AI have combined to gut the kinds of jobs that once gave men a sense of status and identity.

As social scientist Richard Reeves points out in his 2022 bestseller “Of Boys and Men” (also the name of his Substack newsletter), these trends have most impacted blue-collar men and African-American men of all backgrounds. Among the broader population of young men, the impact shows up in stark ways: Many appear to be dropping out of society altogether, with 1 in 7 young American men aged 16 to 24 classified as NEETs — not in employment, education or training — in 2024.

In the U.S., women are surging ahead in education, earning almost 60% of bachelor’s degrees and an equal percentage of master’s degrees. And the imbalance starts early, with girls more likely to be “school-ready” at age 5. They read more than boys — a gap that increases throughout high school — and make up two-thirds of top students by GPA. Meanwhile, boys are twice as likely to be suspended and three times as likely to be expelled from high school.

Nowhere is the crisis with boys and men as evident — or as headline-worthy — as in the area of relationships. Fifteen percent of young American men say they have no friends, five times the rate in the 1990s. And while young men pine for the days in which they could be providers, almost half don’t even date. Indeed, one of the first questions raised during Galloway’s recent appearance on “The Daily Show” involved this startling statistic: 45% of men aged 18 to 25 have never approached a woman for a date.

Beyond that, the fact that most young men are out of sync politically with their female counterparts can’t be helping their romantic prospects. A recent Gallup poll revealed that American women aged 18 to 30 are 30 percentage points more liberal than their male contemporaries.

Add to this a global pandemic that drove young men to isolate in their rooms and on their screens, and sprinkle in the aftermath of #MeToo — an enormously important movement for young women but one that also left many young men anxious about saying or doing the wrong thing — and what’s left is a generation of guys adrift from traditional markers of masculine identity: economically displaced, socially isolated, ideologically estranged.

It’s not as if the current crisis among boys and men has gone unnoticed. Indeed, back in the early-to-mid 2010s — well before the pandemic and #MeToo — writers such as Hanna Rosin and Christina Hoff Summers had sounded the alarm.

In a way, their work has extended to some of the more recent books exploring the crisis. For example, reporter Ruth Whippman explores emerging brain science to suggest that boys are, counterintuitively, more vulnerable and fragile than girls, and are in need of more, not less, care and nurturing.

In her 2024 book “BoyMom: Reimagining Boyhood in the Age of Impossible Masculinity,” Whippman reports that a baby boy’s right brain hemisphere — which helps with emotional regulation — develops more than a month slower than a newborn girl’s. Studies show that executive function and impulse control in boys can lag up to two years behind that of girls until age 25. This has major, if underappreciated, impacts on boys’ relationships, parenting, education and more.

What appears to be new is that over the past few years, there’s been a rise in men taking an interest in the crisis, which is both heartening and ironic — a kind of meta-comment on the problem, if you will: Guys are finally getting it together to face the challenge.

Chief among these is Reeves. While “Of Boys and Men” is now a few years old, it’s impossible to talk about the latest crisis without considering how Reeves and his many appearances on cable shows, radio and podcasts have shaped the current debate.

A social scientist and self-described “policy wonk,” Reeves’ biggest contribution may simply be his deeply measured approach. Whether he’s on Lost Boys — a podcast series squarely aimed at tackling the current crisis — or Smerconish’s recent CNN special, Reeves has become something of a trusted guide for others focused on this issue. Galloway calls Reeves his “Yoda on the subject.”

It may be that in a crowded space of critics quick to reach for controversy, Reeves’ nuanced approach antagonizes those on the far ends of the political spectrum. Describing how liberals have dealt — or, as it happens, not dealt — with the problems of boys and men, Reeves argues that among other missteps, the left has often ceded ground on this issue due to its tendency to reflexively describe male behaviors with unhelpful labels (like “toxic masculinity”), or its failure to see that gender inequality can “run both ways,” as he writes.

Meanwhile, the right has been more effective in appearing to champion the needs of boys and men — consider U.S. Senator Josh Hawley’s book “Manhood: The Masculine Virtues That America Needs,” or Tucker Carlson’s documentary “The End of Men” — but Reeves says these, too, don’t do men any real favors.

For example, if liberals tend to downplay biological sex differences for fear of setting back women’s gains, then conservatives tend to overemphasize these.

More to the point, conservatives tend to look to the past — often idealized versions of the past — rather than the future for inspiration. As Reeves says: “That’s not a winning recipe in a rapidly changing world.”

In “Notes on Being a Man,” Galloway reveals a similar talent for framing the current crisis as both urgent and best not left to the extremists on either side. Indeed, it’s not for nothing that Galloway and Reeves are now often grouped together and even castigated for their brand of moderation. (Among his various shows, Galloway hosts a podcast with Fox News personality Jessica Tarlov called Raging Moderates).

In the book, Galloway leans into what he calls “an aspirational vision” of masculinity — a pointedly nonmisogynistic counterpoint to the Jordan Petersons of the world. Galloway’s mission is less about shaping a new vision of masculinity than rehabilitating the one we’ve got.

In “Notes on Being a Man,” he picks through well-told, often funny pieces of his biography from boyhood through fatherhood, and identifies a trio of traditional male attributes — protecting, providing and procreating — that can form a code of masculine responsibility. He goes to lengths to clarify that these traits are to be defined broadly: For example, by “procreating” he doesn’t just mean sex, but also the emotional investment of raising and nurturing the next generation.

In chapters that alternate between his own story and his prescriptions for greater success, Galloway suggests: leaning heavily into work, especially when you’re young; working out; making friends at all stages; and being a more available father. Ultimately, he writes, the goal of any man should be to become someone who adds “surplus value” — that is, he gives back more to society than he takes.

The suggestions are so commonsensical as to feel anodyne. Yet it’s also easy to pick holes in some of what Galloway argues. On TV and podcasts, he can come across like a human baseball-pitching machine, spitting out facts and stats with a kind of “tech bro” fluency that can read as glib rather than informed. That said, he’s also quick to poke fun at himself in a way that undercuts any self-seriousness, as he frequently does on Pivot, a popular podcast he hosts with the journalist Kara Swisher.

And while his own story is a compelling one — he humorously leans into his own modest background, including a single-parent (mother) household, lackluster academics and unimpressive dating history — his prescription for success doesn’t really account for underlying causes of male instability, including mental health issues like depression and ADHD, which defy easy fixes.

A bigger problem for Galloway is that, like male influencers of all stripes, his recommendations are largely aimed at self-improvement — which is, by its very nature, an individual enterprise. But as Reeves and others have pointed out, many of the challenges boys and men currently face — especially with respect to education and employment — would require real government policies and other structural changes to address.

Still, there’s something novel about Galloway’s brand of influencer. With his code of responsible masculinity, he offers both younger and older men, but particularly the latter, a compelling alternative to the current stream of misogynistic, opportunistic hucksters. I nodded in agreement when, on “The Daily Show,” he chided the men of his generation — those most structurally advantaged by this country — to step up and mentor boys. Here he echoed a point Reeves often makes. “If we want better men, we have to be better men,” he said.

Something else Reeves and Galloway have in common is a belief that, thanks to feminism, the past 60 years have given women ample opportunities to discuss what changing roles have meant for them.

But it can feel like men haven’t necessarily had — or sought out — a similar conversation about what their changing roles might mean. One takeaway from absorbing the current spate of books, podcasts and cable news specials is that instead of demanding that far more difficult conversation, we’re still stuck simply debating masculinity today as a crisis.

At the same time, it’s clear that Reeves and Galloway have absorbed many of the lessons of second-wave feminism in ways that feel notable and distinct from a previous generation of male writers on masculinity. Both Reeves and Galloway are decidedly inclusive and emotionally intelligent. Both are quick to point out that the debate isn’t a zero-sum game: We can focus on the problems of men without blaming women.

Meanwhile, there’s continuity between Reeves and Galloway and a previous generation of male writers. Like Bly, both Reeves and Galloway speak to the urgent need for mentoring. In “Iron John,” Bly talked about boys needing older men to initiate them into manhood, to pass down some essential knowledge about what it means to be a man. Strip away the forest retreats and the poetry, and Reeves and Galloway are making remarkably similar arguments.

They’re also revisiting Bly’s case for the importance of male-only spaces. In a recent New York Times op-ed, Reeves pointed out that the last time boys faced a similar crisis — at the dawn of the 20th century — America responded by creating civic institutions like the Boy Scouts, Big Brothers and the YMCA. But most of these organizations are now coed, leaving fewer dedicated spaces for male guidance.

But this also requires men to start being there for one another. In “Notes on Being a Man,” Galloway pushes men to show up for each other — as fathers, as mentors, as friends. And noting on CNN the enormous waitlists for boys seeking mentors at organizations like Big Brothers Big Sisters, Reeves was even blunter: “Men … we need you.”

Such a message has long been front and center in African-American communities — consider 1995’s Million Man March in Washington, with its message of responsibility, brotherhood and community.

But 30 years ago, this kind of talk about male spaces rubbed feminists, and in particular white feminists, the wrong way — understandable in a world that still denied women so much. The cultural critic Jill Johnston famously excoriated Bly, arguing that his men’s movement amounted to a retreat from feminist gains. To Johnston, “Iron John” demonstrated “the threat posed to many men by even a hint of women’s freedom.”

Yet it’s instructive that some of the most prominent recent critiques of Reeves and Galloway also pick apart the very idea that we need to worry about boys and men. Writing in The New Yorker, Jessica Winter concludes that the current crisis isn’t uniquely male, but a broader economic and social one afflicting everyone. By framing it as primarily a male crisis, she argues, writers like Reeves and Galloway perpetuate the belief that men deserve special concern when facing the sorts of struggles women have long endured.

“What these pundits are nudging us to do, ever so politely, is accept that women, in the main, are accustomed to being a little degraded, a little underpaid and ignored and dampened in their ambitions, in ways that men are not and never will be,” Winter writes.

But Winter seems unable to read concern for struggling boys and men as anything but an attempt to restore male dominance. The dismissive tone in much of her essay helps to underscore why so many young men have stopped listening to mainstream voices — and why they’ve found refuge in the manosphere, where at least someone takes their plight seriously.

Criticism like this reflects a kind of scarcity mindset. It’s indicative of the zero-sum mentality that both Reeves and Galloway have highlighted, a faulty worldview in which to show concern about men is to stop caring about women, that to acknowledge the former’s suffering somehow diminishes the latter’s struggle. Unfortunately, it also does little to address the very real threats to young men’s well-being.

It’s not that some of this feminist pushback isn’t valid. Despite real gains in education and the workforce, we’re moving backward when it comes to women’s gains around the world. And here in America? It feels as if we’re in a moment of full-blown backlash, with reproductive rights under siege and very few of the powerful men in Jeffrey Epstein’s orbit, even today, facing genuine consequences. When women look at men asking for empathy, it’s easy to see why some might see that as a distraction from the biggest problems at hand.

Where does that leave us? There’s the sense men want to feel seen and validated at a time when the traditional indicators of masculine identity are crumbling. And as feminist writers have long argued, women want to feel safe and respected, to see their whole selves given equal space in the world. But no matter how well-intentioned, it can seem like we’re all simply talking past one another.

But just as championing women’s progress doesn’t hold men back, books cutting to the heart of what’s ailing boys and young men needn’t detract from women — in fact, quite the opposite. As Smerconish remarked: “We owe it to the women to help the men.”

At any rate, if the past two centuries are any indication, there will be a similar wave of books and shows soon enough. Will the conversation about masculinity — perhaps led by men — have evolved beyond its current framing of an identity in crisis? Will criticism of these books and shows seek a deeper understanding, or will it minimize the genuine anguish at their cores?

Will we continue talking past one another?

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.