On the morning of Dec. 4, a young man lurked in the streets of midtown Manhattan, creeping up behind UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson and gunning him down outside his hotel. The brazen attack first generated shock, but within hours, the rawness of shock turned into a kind of glee on social media, accompanied by jokes and potential justifications for what one criminologist called a “symbolic takedown.” The killing represented not so much a personal grudge against a single individual or the company he led but a strike against America’s widely loathed private health insurance system.

Graffiti honoring Luigi Mangione appeared from the streets of Seattle to the University of Turin in Italy. Suddenly, murder ballads became a tool to understand or even join the general lionization of the suspected killer. Americans have always supported murder, we learned, as evidenced by songs as different as “Goodbye Earl” by the Dixie Chicks (now just the Chicks), “Hey Joe” (made famous by Jimi Hendrix) and “Pretty Boy Floyd” by Woody Guthrie. Whereas “Goodbye Earl” is about a woman murdering an abusive partner, “Hey Joe” describes a man’s murder of his unfaithful spouse and “Pretty Boy Floyd” tells the story of a folk hero robbing from the rich and giving to the poor. Moral differences aside, these tropes blend into a common matrix of murder.

When Mangione was charged as the alleged killer on Dec. 9, researchers found social media posts, follower lists and a biography that indicated Ivy League credentials with an elite, private high school education and at least one politician in the family. His online profile resembled an episode of Joe Rogan’s podcast — some interest in left-wing politics alongside ruminations on the return to tradition as a prescription for the demographic decline of Japan, gym advice, commentary on evolutionary psychology and posts about psilocybin mushrooms and the denizens of the so-called “Intellectual Dark Web” — a group that transcends partisan divides and includes a variety of figures who have made their names by embracing debate and challenging orthodoxies.

Mangione’s apparent support for Peter Thiel’s renegade Silicon Valley politics and Elon Musk’s war against the “woke mind virus” caused some whiplash for those who were invested in the notion that this vigilante killing was different from the array of right-wing murders, arsons and threats seen over the last decade. Mangione apparently left a four-star review on his Goodreads account for a book by Ted Kaczynski, the so-called Unabomber, who railed against both the effects of technology and leftist campaigns for gender equality and minority rights. Like Mangione, Kaczynski’s ideology included a variety of left-wing and right-wing sentiments. Their admirers similarly span the political fringes in interesting ways, and Mangione is now also being charged with terrorism.

Deleted tweets reviewed by Business Insider even showed Mangione sharing a post from a fascist account featuring disdain for doctors. But no revelations about Mangione’s worldview could have blocked the mass revelry. As photos of his masked face circulated, memes adulated his good looks and expensive clothing in a real aestheticization of violence. To say that the alleged act is popular with the general public would be an exaggeration. According to an Emerson poll, 16.5% of voters find the killing “acceptable.” However, among voters younger than 30, more find the killing acceptable than unacceptable (41% to 40%). By comparison, voters in every other bracket found the killing unacceptable by wide margins. It seems clear that the support for this shooting bears a significant generational marker. The levity with which the Dec. 4 murder has been treated seems to enable young people, in particular, “to conjure something funny or silly or joyous out of [their] hate,” as The New Yorker’s Jessica Winter put it, or rather to express their hatred with the ardor of youth.

Despite a fake manifesto posted online that referenced heartbreaking stories about his mother, the document purportedly found on Mangione comprises just 262 words, presenting no pretense of sympathy or deeply personal narrative. He suffered from spinal pain; he became enraged at the health care industry; he killed a health care CEO. It does not appear that specifically right- or left-wing ideology drove him.

While being led into the courtroom, Mangione appeared to shout, “This is completely out of touch and an insult to the intelligence of the American people and its lived experience.” Despite his affinity with the niche, right-wing “Gray Tribe” of the internet, a Silicon Valley-linked tendency named for its rejection of red and blue partisanship, Mangione’s attack seems to have touched a deep chord in a changing country, and that’s precisely why the fandom that he has inspired across the political spectrum is so eye-opening.

Some have drawn parallels to other periods of conflict in postwar history. A quick glance at Google Trends illustrates an important spike in searches for “Years of Lead” in recent days, and the comparisons to the period of political violence in Italy from 1976 to 1982 appear less impressionistic upon deeper inspection. The important thing about this comparison is not simply the phenomenon of political violence but the culture in which it occurred.

Scholars generally date the Years of Lead to the rise of murderous political violence and tit-for-tat attacks by left-wing and right-wing groups between 1976 and 1982. The longer timeline stretches back to the 1960s, when far-right reactions to Italy’s shift to the left took the form of bombings, which set the stage for the rise of violence in the 1970s. This rise was seen throughout society, including in mafia groups that were connected, in a number of cases, to factions of both the left and right.

Several similarities with the contemporary U.S. jump out immediately. In Italy, the trouble began with the emergence of a center-left from a system characterized by a political consensus around technocratic governance on behalf of “the people.” The same can be said for the U.S. during the 2010s, as large-scale social movements like Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter pushed a generally centrist Democratic Party in a more progressive direction. In Italy, the “center-left formula” brought about the emergence of reactionary coup plotters attempting to subvert the center-left and the perceived threat of communism that it might have hidden. Elements of this historical process of center-left consolidation and far-right reaction parallel the emergence of Trumpism, with its appeal to paramilitary groups and the insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021, to prevent the transition to a center-left government from taking place. In Italy, a subsequent response against coup plots and their violent manifestations erupted in strong but undisciplined left-wing movements disconnected from parties and their institutions. Potent drugs flooded onto the streets — heroin and cocaine in Italy then, fentanyl in the U.S. today — increasing crime and deaths of despair.

In the case of the Italian model of the 1970s, powerful cultural change occurred in the form of the referendums for divorce and abortion, accompanied by centrist panic and challenges to patriarchy from left-wing tendencies and groups. In the U.S. today, the emergence of a transgender rights movement has stoked backlash from moderates in the Democratic Party as well as from so-called “radical feminist” groups while conservatives put abortion back on the cultural battlefield. The Italy of the 1970s faced upheaval related to significant technological transformations, ushering in expanded market access and automation, while today’s U.S. lives in tremulous uncertainty about the future of artificial intelligence and the blockchain-driven possibilities of Web3. International conflicts like the Yom Kippur War manifested domestically in Italy during the 1970s in ways that polarized and radicalized dissenting groups — for instance, by accelerating inflation. The Italian party system of the 1970s found itself on the brink of a broader change toward the inclusion of drastically different political cultures and agendas while the U.S. today lurches toward a new system of oppositions, from trade to foreign policy to immigration. Lastly, while Italy saw the outbreak of casual violence, both political and otherwise, within this complex period of transition the U.S. also faces a relative rise in hate crimes and unrest.

According to Armed Conflict Location and Event Data, since peaking at nearly 60 political violence events in June 2020, the U.S. has racked up a fairly steady average of 15 events per month nationally. 2020 and 2021 also saw a massive increase in gun violence, which has still not dipped to earlier levels, according to the Gun Violence Archive. While those metrics have sloped downward since 2020, data from the FBI’s hate crimes statistics show an overall increase of incidents, offenses and victims from 2022 to 2023. Indeed, hate crimes have risen every year since 2014, and since 2020 they have exceeded previous records with every passing year. And then there’s far-right violence — a phenomenon less articulated in the data but apparent in mass shootings and low-level attacks on electricity infrastructure that bear the same ideological stamp as the right-wing massacres in 1970s Italy.

Amid the rise in hate crimes and gun violence, Princeton University’s Bridging Divides Initiative shows that threats and harassment against elected officials have only grown, increasing by more than 50% in 2023, to 505 threats. As of October this year, the average of about 1.6 threats per day exceeded 2023 levels. More than 50% of local elected officials surveyed by the initiative experienced harassment in the fourth quarter of 2024, and nearly 40% of them experienced threats.

It feels almost facile to place the UnitedHealthcare killing and its fandom in this climate of rampant intimidation of functionaries and officials, with the vast majority of threats coming decidedly from the right. But the connection is real. Stubborn levels of violence in society sets the stage for a return to previous peaks of political violence while the increase of threats against officials indicates a climate of intimidation and coercion. All of this reflects trends similar to what historians have called Italy’s “creeping civil war,” classifiable in military terms at the end of the 1970s as a “low-intensity” conflict.

In a number of salient ways, however, the U.S. in 2024 is very different from Italy in 1978. No armed groups have emerged in the U.S. marrying their violence with revolutionary rhetoric. The U.S. does not have a parliamentary system in which administrations can form and then crumble virtually overnight. The conditions of organized crime and casual violence in the U.S. today are very different from those that created the powerful and sophisticated mafia clans of 1970s Italy. Italians in the 1970s had been through the anti-fascist Resistance just 30 years prior — a civil war with a clear-cut end that saw the victorious side rise to a mythic stature. The guns of the Resistance are not buried in our backyards in America. But then, they don’t have to be. And in some ways, the same technological, political and social problems only seem more advanced, with similar causes, contradictions and openings for change.

In the U.S., people share memes about the suspect, finding enjoyment in the momentary collapse of the symbolic order. Those who uphold or represent that order are challenged by this milieu for their refusal to partake in the fun. Some accused of standing with “the System” have even been threatened with ominous indications over who will be “next.” In Italy during the 1970s, a similar climate emerged around efforts by some leftist intellectuals to sympathize with, explain or condemn the armed struggle. Given the return of comparisons to the Years of Lead, the outcome of that intellectual climate and its relation to rising violence may prove instructive in the U.S. today.

The discourse surrounding violence became particularly intense following the police slaying of activist Pier Francesco Lorusso at a Bologna protest on March 3, 1977. Massive riots swept across the country. Bologna flew into a mass insurrection, with Molotov cocktails thrown at police, rolling gunfights, looting and whole neighborhoods shrouded in tear gas. One participant later remarked, “I used up … all the ammunition that I had put aside in years of obstinate parsimony.” Rome, too, descended into a chaos of gunfights and looting, with a rioter recalling, “Not a shop window was left standing.”

Some groups who participated in mass violence, like the Rome-based Autonomous Workers Committees (Comitati Autonomi Operai), argued that armed struggle, specifically, was an idealistic pursuit that did not suit the material exigencies of the moment. Other radicals, like those of the Chalk Circle (Il Cerchio di Gesso) in Bologna, embraced the culture of violence. Intellectuals like Umberto Eco went on to call for discerning people to understand the culture in which so much rioting and even armed struggle found acceptance.

On April 10, 1977, the center-left magazine L’Espresso released an article by Eco called “How Do the New Barbarians Speak?” on the Bologna autonomists, who had been both the most riotous and the most aesthetically interesting. In this piece, Eco declared that the “high culture” attuned to the literature of French Surrealists and Russian Futurists was unable to comprehend the avant-garde of the present day. “That high culture that understood the language of the divided subject very well when it was spoken in the laboratory no longer understands it when it finds it spoken by the masses,” he wrote. The new generation came to the avant-garde through rock ’n’ roll and experimentation at parties, but it came to the avant-garde all the same. However, in coming to the avant-garde free from the controls of the aesthetic laboratory, Eco concluded, the new generation reformulated the aesthetic vitalism of Nietzsche and the Italian futurists who inspired Fascism.

For Eco, the urban guerrilla warfare manifested a youth culture, “the generation of the year Nine” (the number of years since the uprisings of 1968). The violence came from something like a vanguard movement raised on revolution, which maintained the haughty airs of high culture while embracing low culture.

Eco did not sympathize with the armed groups; he simply saw their philosophy as running contrary to a revolution. “It is one thing to prefigure the assault on the Winter Palace in a great, symbolic celebration and another thing to actually take the Winter Palace,” he went on to write in his next column. This discourse on the avant-garde ruffled feathers within the Communist Party, the second most popular party in the country, which argued that Eco came dangerously close to rationalizing the rebellion instead of marginalizing it.

Eco’s companion Alberto Asor Rosa attempted to articulate his own analysis of the situation in a critical response piece published by L’Espresso: “But While We Speak, They Go Boom.” For Asor Rosa, a devoted opponent of armed struggle and member of the Communist Party, Eco’s critique of the young avant-garde relied on a cheap effort to connect Nietzsche and Futurism to Nazism and Fascism, which required an unnecessary jump. More importantly, Asor Rosa believed that arguing on the level of theory and aesthetics did not make the necessary move to the level of politics, where the left needed to prevent more violence and encourage workers’ organization.

In Asor Rosa’s opinion, elaborated in a volume called “The Two Societies,” also published in 1977, the Italian dilemma resulted from a division between “two societies” — one professional and unionized, the other precarious, young and angry. The crisis between the two societies caused “the broad, widespread, profound need to relate in a different way with politics.” As a result of the sweeping social divide, he later wrote, a “sort of indulgence was quite widespread back then, inclined to explain and sometimes justify.” Within this permissive context, “boundaries between protest, subversion, and armed struggle were then rather blurred.” The social crisis represented not just a problem for the right wing but a major disruption to decades of left-wing political organizing. “It was as if an atomic bomb had fallen on what had been an organized and programmatic confrontation between culture and politics in previous decades,” Asor Rosa later explained. Only by moving from theoretical discourse to political organizing could the pieces be reassembled, he thought.

The UnitedHealthcare killing divided today’s journalistic territory along similar lines, into two somewhat familiar camps: one in which publications like Teen Vogue and The New Yorker outline an understandable rationale behind the crime and its fandom, and the other where columnists for The Atlantic and The New York Times decry that discourse on the basis of the senselessness of the act of murder. For some press voices, the idea that people are rightly angry about the health care system seems to merge with the sense that people are rightly excited about the murder. Meanwhile, dissenting audience responses — the provenance of which is always questionable online — add to the pressurized situation. In short, the discussion over the cause of the crime exposes new fault lines in political culture that cut across the political left and right.

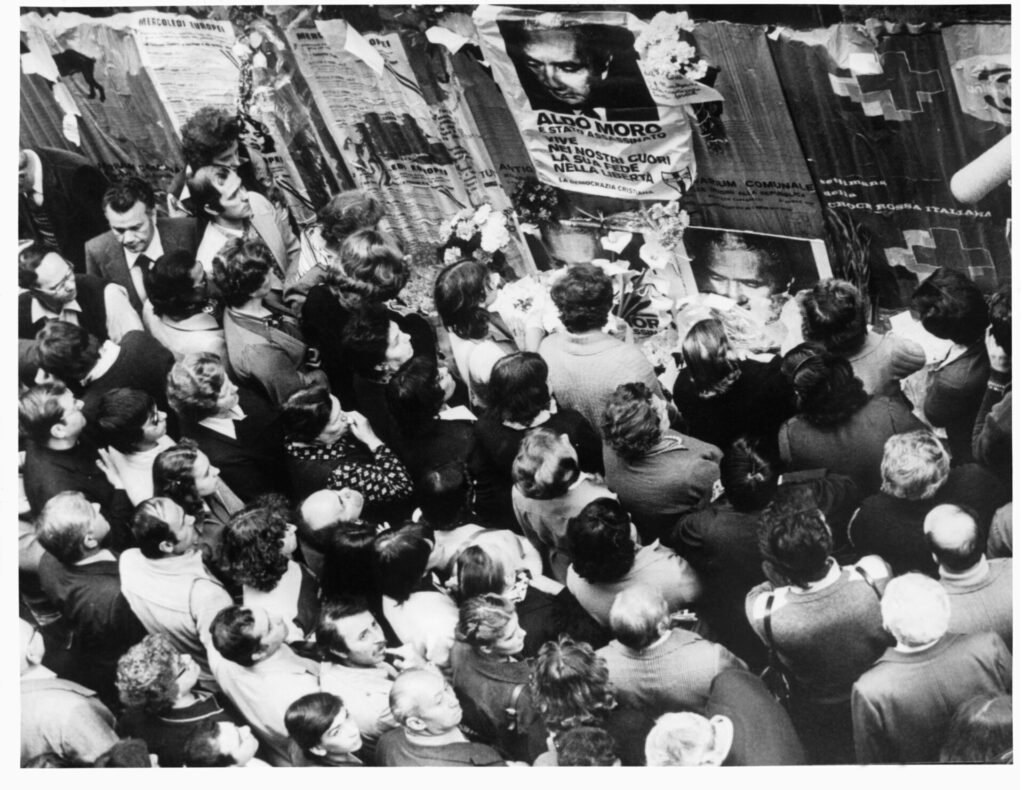

Months after the dispute between Asor Rosa and Eco over violence and the generational divide, a new crisis emerged among some of Italy’s greatest thinkers. When the Nobel Prize-winning poet Eugenio Montale told a journalist he would not engage in the trial of the armed group the Red Brigades because he would be “afraid like the others,” the jurist and former Resistance fighter Alessandro Galante Garrone intervened, declaring in the center-right paper La Stampa that “the State is us.” Writing approvingly of Galante Garrone in the Milanese newspaper Corriere della Sera, the novelist Italo Calvino called for “democratic citizens” to defend the state against the armed struggle. At this point, Sicilian polemicist Leonardo Sciascia bucked the trend, declaring he would not serve as a “caryatid” supporting an incompetent, bureaucratic state ruled by a political class that would not leave power except by “suicide.” The clash became more serious at that point, with Communist Party leader Giorgio Amendola, whose father was killed by the fascist armed squads known as the Blackshirts during the 1920s, comparing those who would not defend the state to the intellectuals who bent the knee to Mussolini. Taking place in the context of the widespread riots of 1977 and the following year’s kidnapping and execution of Christian Democratic leader Aldo Moro by the Red Brigades, the national dispute on “courage and cowardice” seemed to offer a choice between an idealized state that nobody believed in and a societal disintegration that everyone feared.

In general, the violence of the armed struggle correlates to a reordering of social hierarchies, which takes place through cultural tumult. One can acknowledge that the precarious status of many people drives them to lash out in the form of celebrating murder while recognizing that murder remains wrong. Yet explaining the former can easily seem mutually exclusive with the latter. To defend the position that murder is wrong, when that murder takes a purely symbolic quality, elevates the subject to an abstract level on which one is forced to contend with the positive value of the symbol being attacked. The responsibility thus changes from criticizing the atmosphere of a generational trend to defending the state from it. In Italy, the pandemonium latent within this dilemma led to a deepening war among left-wing intellectuals — from the need to contend with the ideas of the young, wild counterculture to the responsibility to defend the state from its violence.

Could today’s exuberant social media posting from left and right set the stage for tomorrow’s repressive conditions fostered both by armed political violence and the police responses that they inevitably incur? Lying beneath Trump and his acolytes — from podcasters and influencers to religious demagogues and tech evangelists — is a prevailing culture characterized by “risky business,” mounting gambling debts and deep-seated anger about a socioeconomic paradigm of rule by experts of the “business class” installed generations ago. The prevailing spirit almost lends itself to that of the armed struggle, emphasizing not the direct effect of one’s actions but the secondary reactions that it causes.

If the violence of mass deportations, the slashing of workers’ rights and the pardoning of the “Jan. 6ers” leads to counterviolence like the low-intensity conflict of 1970s Italy, who will be surprised? Have we not already crossed the Rubicon enthusiastically with such widespread support for vigilantism?

At the end of the Years of Lead, demonstrations of power replaced mediating efforts between the movement and the “groups.” While some of their targets were corrupt and generally disliked, armed groups of the left also murdered left-wing journalists, architects and union organizers. In at least one case, they accidentally stalked and killed the wrong person; in another case, they videotaped a forced confession from someone completely innocent of their accusations before photographing themselves murdering him in an abandoned farmhouse and sending the image to the press. The point is not that an armed struggle in the United States could go into such dark places; it is that it certainly would.

In the words of former Red Brigades member Enrico Fenzi, murder “was accepted as something that had its own reasons, and imposed its own yardstick. Killing became ineluctable, indisputable.” Murder existed outside of deliberations over right and wrong, necessity and impossibility that maintained any connection to social conditions, but it demonstrated something to the public. The armed struggle abandoned things like murder taboos for what Fenzi’s comrade Barbara Balzerani called “the all-or-nothing logic of winning or dying.” Inured to murder, the armed groups applied a metric for judging ethical decisions based on ideological frameworks that could not see any future outside of a revolution or civil war for which almost anything became justified.

Sandro Portelli of Il Manifesto, one of the most influential radical Marxist groups to reject armed struggle in Italy, told me a couple of years ago: “We were all living in a bubble, we only talked to one another, we reinforced our own mythologies.” That description seems to map onto today’s coordinates quite well. We are all living in bubbles created by ourselves and secured by algorithms. Our culture of violence is feeding into mythologies that do not line up with our end goals. In a mass culture increasingly defined by social media use, the prospect of individuals feeling motivated — not only by the UnitedHealthcare murder but by the wave of unabashed enthusiasm for it — to commit misguided murders becomes tragically understandable.

And to be clear, this is not merely about the left. During the Years of Lead, fascists, with their infiltrators and agents provocateurs, appreciated a number of the actions of left-wing armed groups, even emulating them in the case of the Third Position and the Revolutionary Armed Nuclei, both of which emerged from the feverish violence of the mid-1970s to create less organized versions of the paramilitary groups that formed in the previous generation. So it should not be surprising that even before the alleged UnitedHealthcare killer’s identity became known, a fascist account on the social media site X used the image of the UnitedHealthcare slaying in an online death threat against the left-wing Texas journalist Steven Monacelli.

In the other direction, one meme circulating on the left places Mangione in a format used by fascists that depicts mass shooters in the iconography of saints. While this “Saint Luigi” meme continued to circulate online, a 15-year-old female inspired by the same “accelerationist” mass shooter meme of “sainthood” carried out her own school shooting at a private Christian school in Madison, Wisconsin on Dec. 16. The shooter’s reported manifesto specifically referenced as “an Ultimate saint” a Turkish neo-Nazi who livestreamed his knife attack in the city of Eskisehir in August this year. With the entrance of “Saint Luigi” into the canon of killers, one can see how Portelli’s “enforced mythologies” make a system of reinforced violence the ends and not just the means.

In the Italian armed struggle, both left and right hoped to bring “the System” crashing down, although the morally abominable right-wing groups targeted random civilians far more regularly. The right wing called their strategy the “disintegration of the System,” and fascist accelerationists who seek the downfall of liberal democracy by “accelerating” political violence on all sides still endorse this approach. Yet who, today, would cast themselves as a supporter, a “caryatid,” of “the System,” recalling the words of Sciascia? Not even the president-elect.

One is led today, in the same manner, to stand neither with vigilante murder nor with institutional greed. However, this answer is not enough. In light of such political violence, it is necessary to defend the state, despite its inefficient bureaucracies of forms, functionaries and guarantees. The state must be defended because it can actually help people through the social safety nets it provides, however imperfectly.

Whether or not they realized it, though they ruined many lives, the armed groups in Italy during the Years of Lead played only a small role in the larger process of painful, slow-motion transformation away from socialism. The idea “that they were leading the working class,” Portelli told me, “was one of the great delusions.” Those enthusiastically embracing symbolic vigilante murder risk rejoicing in a vast wave of reaction that will undermine the thankless task of building movements.

Here is the danger with the sort of ecstatic approach of social media, which can imitate “the crowd” that acted as the basis of mass politics a century ago: One forgets to think. Seeking to explain the killer’s motives without justifying them does not make one a coward, but we must not lack the courage to be rational, to discuss real problems and to caution against potential threats. That is why the armed struggle, for all its manifestos, has almost always been anti-intellectual. Belgian fascist Leon Degrelle once encouraged his supporters by saying, “You must get going, you must let yourself be swept away by the torrent.” But instead, we must think; we must refuse to be swept away.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.