A lady donning an abaya knelt on the floor, thumbing through the pages of a thick, worn book. Her daughter watched on beside her.

I was standing in the premises of the Palestine Branch, a prison on the outskirts of Syria’s capital Damascus. Following the shock overthrow of the Bashar al-Assad regime by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), tens of thousands of prisoners allegedly fled the facility, as they had from other massive prisons such as Sednaya.

The lady didn’t want to be named and wasn’t keen to be interviewed. When I asked why her son was taken to prison, she answered, with a defiant look in her eyes, “Do they need a reason?”

The response was an obvious allusion to the tens of thousands of arbitrary imprisonments carried out by the regime. Next to her was a pile of 50-odd Syrian passports. A man was sitting in front of that pile, opening each passport then casting it aside. A couple of feet away, a few rebels lounged on broken chairs, some with cigarettes dangling from their fingers, most armed with a rifle.

Unlike Sednaya, where members of the media and families of prisoners swarmed through the prison gates in large numbers, access to this prison was heavily restricted. The first time I went to the Palestine Branch, armed guards demanded a press permit issued by authorities. When I returned two days later with my paperwork, they expressed a reluctance to let me in, but after a few minutes of waiting and insistence, they agreed to show me around.

Yasser, a member of HTS, and another rebel accompanied me to the prison building. I asked them if conditions in this prison were similar to those in Sednaya. “They’re worse,” they replied, barely glancing back at me.

Yasser, who used to be a business administration student before the Syrian revolution began in 2011, told me that back in 2012, he himself was a prisoner at the Palestine Branch. Pulling wide the side of his mouth with his index finger, he pointed out missing molars. “They broke my teeth — three on the right, one on the left, and one on the top, five in total,” he said. “They wanted us to admit that we were terrorists. Everyone from the Free Syrian Army had to admit to being terrorists.”

Yasser described various methods of torture the prisoners were exposed to. “They break the prisoners and beat them — they hang them upside down and break them till they bleed. They use metal, rifles, they don’t care,” he said. “The only thing they care about is for the prisoner to incriminate himself so that they can negotiate a price for his release. If they don’t find someone to negotiate with, the person just remains in prison.”

Descending muddied stairs, we entered long, dark corridors lined by large rooms. I asked Yasser if he remembered his cell. He said that the prison’s layout had changed too much since he had been one of its inmates. “When someone enters, he’s blindfolded,” he added. “No one knows what he’s entering. That’s the treatment of the regime.”

The rooms still bore traces of life. Lining the walls on each side were blankets with barely any space between them, each clearly serving as the living space of a prisoner. Some of the dark gray blankets had underwear or other clothes on them. At the corner of the room was a dingy-looking bathroom, meant to serve the 20 or so people who lived in the cell. Some of the rooms still had a heavy metal chain securing them. One could nearly picture the prisoners scrambling out through the narrow space of the doors.

The maze-like corridors, each identical to the ones perpendicular and parallel to it, didn’t seem to end. In one of the sections of the prison, I entered a tiny room where Yasser said multiple people were sometimes kept, despite there being only one blanket on the floor. In the corner of the room was a bucket filled with dark orange urine.

At the end of the building was a large room containing metal stands, and at our feet we found thousands of clothes, photographs, ID cards and papers — all evidently belongings of the prisoners. One of the papers I found was the ID of a 16-year-old boy.

Among the items was a set of prosthetic legs. On the floor of the now-flooded bathroom facilities, I also noticed a lone crutch.

The appalling conditions of the prison were in stark contrast to those in the adjacent building, the rooms and corridors of which bore massive Bashar and Hafez al-Assad posters. Each room contained large desks, sofas and libraries, and the building seemed to serve as the home of the prison wardens and officials. Yasser navigated the rooms — one of which had a dentist’s chair, another of which had gym facilities — with a look of disdain. He told me that he, too, was seeing the interior of this building for the first time.

Many Syrians complain about the corrupt practices that were rampant among law enforcement officials in the country. Yasser did, too. “He [Bashar al-Assad] was living in luxury, needing nothing,” he said. “The state collapsed, and the people collapsed, too.”

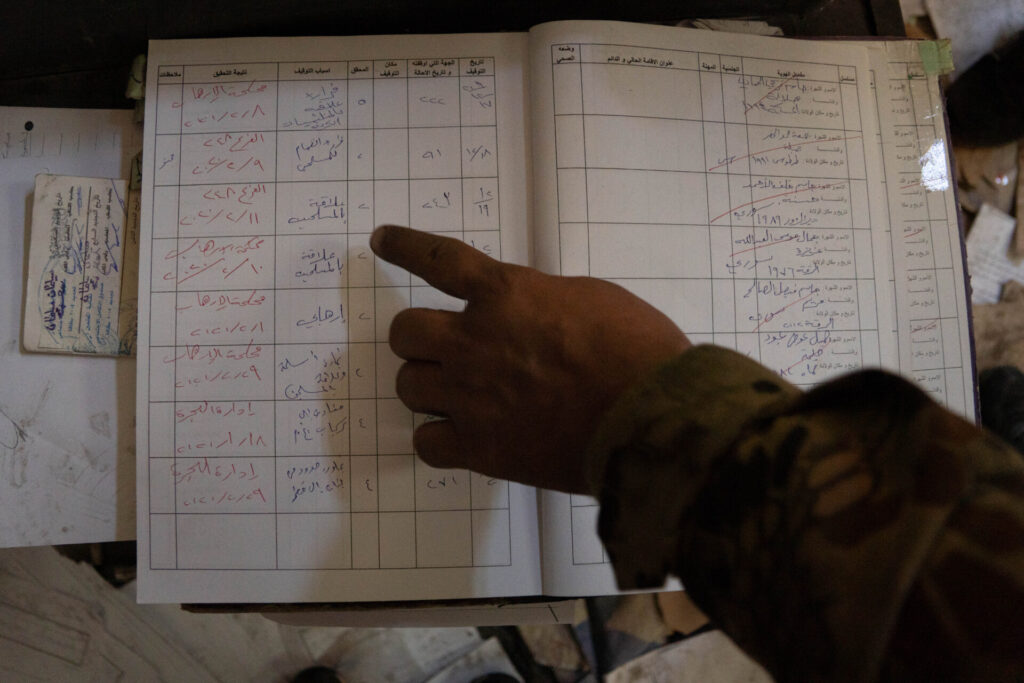

Many of the rooms had been burned down, but they still bore the charred remains of thousands of papers and files related to those imprisoned. I found a camera with a pile of slide films next to it, containing what looked like dated photos of places, families, children and men in suits next to cars. They could be the personal belongings of prisoners, officials or military intelligence. I opened some of the books that were also strewn on the ground in the chaos. Many of them contained rows and rows of prisoners’ names. On one of the tables were a couple of testimonies, marked “top secret.” One of them, from 2015, was of 17-year-old Mahmoud Adnan al-Qassem from Idlib, who was part of the Syrian army but fled, claiming to be mentally unstable. The other one was a testimony of Ahmed al-Mustafa bin Abdelkarim from Deir ez-Zor, who used to work with the government in 2013, transporting fuel and then selling it to gas stations under the supervision of a high-ranking officer in state security.

Damascus’ hospitals, especially the al-Mujtahid Hospital, are now teeming with the hopeful relatives of those who disappeared under the regime. Gesturing to the rebel with us, Yasser told me that he had uncles who disappeared. The rebel, who had an upbeat demeanor, nodded and looked down at the mention of his relatives.

“My cousin disappeared in Qalamoun (a mountainous region bordering Lebanon) in 2016,” Yasser continued. “One month before the liberation, we heard that he was seen in Tishreen Military Hospital. We talked to people and bribed many to confirm he’s alive, but some said he’s there, and others denied it.”

The rebels at the prison told me that there was a high chance of prisoners from the Palestine Branch being at Tishreen Hospital, but when I went there, access was barred even for those searching for relatives. Small groups of people kept coming and going — all of them stopped by rebels in the vicinity.

When I told one of the rebels that I was a journalist and would like to speak to prisoners who escaped the Palestine Branch, if they were ready and willing to share their story, a rebel nodded and asked me to speak to a higher official in a building adjacent to the hospital. “There are no prisoners here,” the official told me. “If there were, you’d be welcome to meet them.”

Guided by tipoffs from various sources about Palestine Branch prisoners being in al-Mujtahid Hospital, I returned there for the third time. A kind doctor accompanied me at my request. We went to three different wards, including emergency and admission, but were told that bodies brought in — or prisoners who survived — were all from Sednaya prison.

Said Bernabia, Middle East and North Africa Program Director of the International Commission of Jurists, said that despite the emptying of prisons under the Assad administration, including the Palestine Branch, “the full scope of the atrocities committed during the past 13 years is yet to be established.”

So many of the people I met were arriving at prisons based on hearsay or guesswork. As I was leaving the premises, I met Souad Mohammad Falah, who was searching for her son, Mahmoud Mohammad Hammadi, who was taken in 2012.

“I have no information,” she told me. “I don’t know if he’s dead or alive.”

With the abhorrent conditions of the prison, the large amount of paperwork that needs to be investigated and limited access to facilities, there is a lot that we are yet to uncover about the Palestine Branch. Yet Yasser is rejoicing in his country’s current freedom.

“Thank God that some prisoners were liberated,” he said. “Everyone’s happy and celebrating, hoping for a better future. Everyone hopes that things go well.”

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.