Amira Brahim, 50, sits with her worn hands folded in her lap, in the living room of her apartment, a short distance outside of Tartus in Syria’s coastal region. A battered coffee pot stands on the table as she sips her small cup of Arabic coffee. “Sweet, that’s the way I like it,” she says, a soft smile spreading across her tan, wrinkled face. Behind her, the layers of white and yellow paint on the walls are chipping away, revealing dark gray concrete.

Outside, stacks of cinder blocks serve as an outer wall of her makeshift garden. Pots made out of plastic bottles line the top of the wall, with flowers sprouting from them. Since December last year, following the Bashar al-Assad regime’s fall, Brahim has gone to great lengths to make the two-room structure, which until recently was a military barracks, her home.

“We settled in the military housing because we didn’t have money to pay rent,” she explains with her thick mountain accent. Brahim, her husband and her children are originally from Dweir Ruslan, an Alawite village in rural Tartus province. “We came from poverty, without a livelihood. We left our home in search of work,” she explains. Two of her sons work making cinder blocks. Lacking the means to pay rent, they took up shelter in a housing compound for soldiers, who fled as opposition forces swept across the country late last year.

During the day, Brahim bakes fresh flatbread on a domed “saj” oven and milks the three goats in her front yard. Both the oven and goats were provided by a recently established cooperative nearby called the Solidarity Fields, which buys the bread, yogurt and cheese from her.

Solidarity Fields was founded two months ago by Suleiman Dakdouk, 59 — who goes by the name of Kastro after Fidel Castro — along with a handful of other activists from Tartus. The co-op draws its inspiration from an organization of the same name that Kastro helped run in Greece, where he lived for nearly 40 years.

In 2017, Kastro and a group of local activists founded a squat in a public school in downtown Athens. Until its forced closure in 2019, when a right-wing government came to power, refugees and locals lived side by side, farming the land and building a community.

Today, Kastro is trying to reproduce this experience in his native Syria by transforming the military barracks from a “symbol of war and destruction into a symbol of peace and life,” as he puts it.

Seated in a worn armchair in Solidarity Fields’ small office space — which also serves as his sleeping quarters — Kastro recounts his childhood, a red keffiyeh draped around his neck. His words are sparse but concise between sips of his potent sage tea and drags from his cigarette. Thoughtfully stroking his gray beard, he recalls how, at the age of 13, he joined a Marxist group and was expelled from school after refusing to participate in mandatory military drills.

Then, at the age of 16, he was tortured by the security forces for his political activities, despite being Alawite — the same minority sect to which the president belonged. He subsequently fled to Lebanon. Kastro returned to Syria the following year, only to be driven into exile once again a year later. This time he fled to Greece, following a crackdown by the Assad regime against political parties in the wake of the 1982 Hama massacre, which killed tens of thousands of people. The bloody crackdown followed an attempted coup by the Muslim Brotherhood, but left-wing parties like the one Kastro belonged to were not spared the regime’s repression.

When the Syrian revolution broke out in 2011, Kastro went to the Atmeh camp in Idlib province to support displaced people fleeing the regime’s bloody repression. Then, when protests escalated into full-blown war, he made the journey back to Greece. Upon his arrival, he helped establish seven squats in abandoned schools and other government buildings for refugees crossing the Mediterranean.

After the fall of the Assad regime in December, Kastro applied for the Syrian passport that the regime had denied him at what he called “the first opportunity” and was finally able to return home. Yet he arrived to the shock of the coastal massacres. In February, after former regime soldiers launched a failed insurgency against the new government, nearly 1,500 Alawites were killed in a matter of days. In the wake of the violence, tens of thousands of residents were displaced.

At that point, Kastro saw “an opportunity to help afflicted people,” he says. “We are filling the gaps left by the former regime. The new government has left government buildings and public lands empty, which we must take advantage of.” Kastro aims to convert more military barracks nearby into housing for two families from the northeastern province of Hasakah.

“I spoke with the municipality, which said it wasn’t legal to occupy government buildings. However, I said the highest law is for women and children not to be in the street,” he recounts with conviction.

Kastro is against aid handouts, drawing on his experience in Greece. “I am against giving people money — to preserve people’s dignity, they must produce.” Instead, he is helping people, like Amina and her family, to be self-sufficient. In April, Solidarity Fields distributed over 1 million organic vegetable seedlings across Syria.

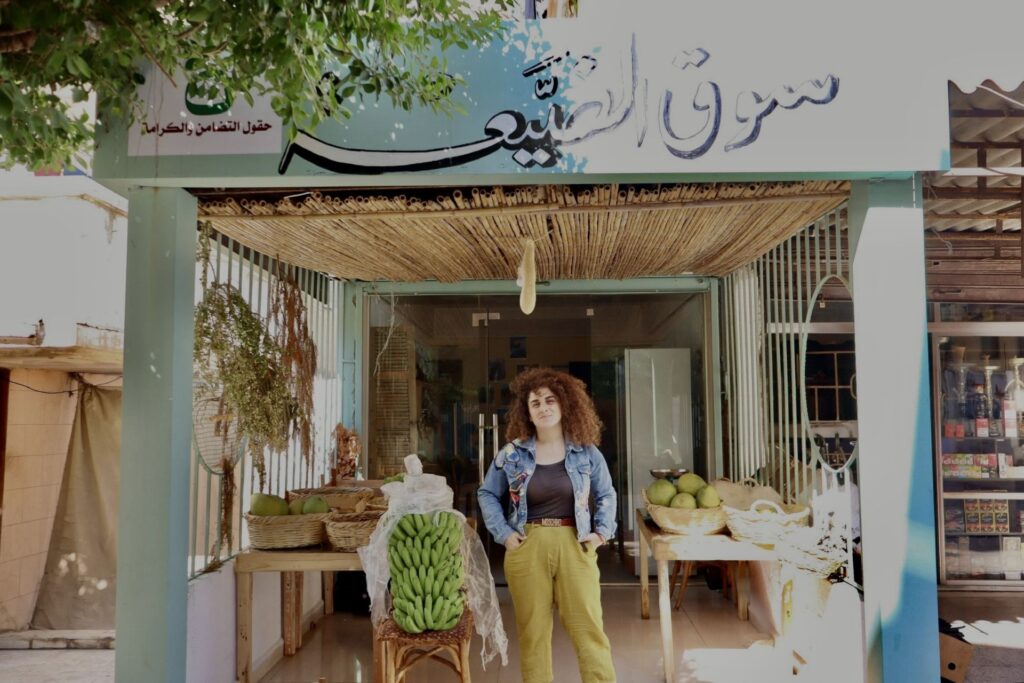

The co-op planted some of these seedlings on the land in front of the military barracks. This winter, the seedlings will grow, and Brahim’s family will sell spinach, cabbage and onions in the co-op’s nearby store, Souk al-Dayaa or “The Village Market.” “We provide a market for organic products they would have trouble selling elsewhere,” Kastro explains. For now, the store is not earning profits and the gap is being bridged by donations, which come from other co-ops across Lebanon and Europe.

“We are killing two birds with one stone: first, by fostering respect for the environment, second by supporting farmers and people in need,” he says.

Kastro’s face darkens as he recalls the massacres that have rocked Syria in recent months. In addition to the coastal killings in March, sectarian violence struck the Druze-majority province of Sweida in July when government troops and tribal forces clashed with local factions, killing over 1,000 people, including dozens of civilians.

“The current regime, like the former regime, sows division to impose control. The massacres on the coast and in Sweida contributed greatly to fomenting sectarianism,” Kastro says. “The current regime has made Sunnis see Alawites as the enemy. However, ‘shabbiha’ [thugs] and officers were from all sects.”

Through collective living and economic ties, Solidarity Fields seeks to bridge these sectarian divides. Brahim’s neighbor, Naema Brahim al-Farraj, 43, is a Sunni woman from Aleppo who lives in the adjacent building with her 14-year-old son.

Originally from Sheikh Nasser, in rural Aleppo, al-Farraj fled after her home was destroyed under the regime’s bombs. Al-Farraj and her son occupied their current apartment, a former army warehouse, in June. “As a widow, I asked for help from the governor for me and my son as we were living in the street, but they didn’t do anything. I kept looking for a place to stay and eventually made this warehouse my home.”

The doors and other metal fixtures were looted in the aftermath of the regime’s fall, so the first thing she did was to install two wooden doors using the meager income her son earns selling cookies in the street. She is unable to work because her back was injured after a car hit her. Instead, she stays at home tending to her garden on the roof, where she grows spinach, parsley, green onions and chard.

In her free time, she makes her way downstairs to make small talk with Brahim’s daughter-in-law, who lives below her. Like al-Farraj, Amal Suleiman al-Awwad, 32, is Sunni and originally from the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. In 2017, her brother was arrested in the Damascus neighborhood of Rukn al-Din during an arrest campaign. He was sent to Sednaya Prison and died there, leaving a wife and two children behind. Her husband, Brahim’s other son, collects garbage with a tuk-tuk Solidarity Fields bought for him, earning a little less than $5 per day.

However, Kastro concedes that much remains to be done to create dialogue. “In Greece, there was a mix of backgrounds, from different nationalities, religions and ethnicities, living together with the local community. However, in Syria, it is more difficult as the reason for displacement is sectarian.” During the war, the Syrian regime targeted Sunni-majority areas, while the new government’s forces have carried out massacres against minority communities.

“We are trying to be stricter about holding more meetings together, to eat together, to talk together, to do activities together, especially for children whose parents are sending them to work.” He insists that men and women should not be segregated in these meetings.

“Our team is diverse, so we can engage all communities — once services improve, tensions will be reduced,” says Huda Shahoud, 33, a co-founder of Solidarity Fields. Her soft face, framed by tufts of brown curly hair, radiates warmth and energy.

“First, the families need to have access to electricity,” she explains. At night, the families gather around a single light bulb, powered by a small battery, to illuminate the darkness.

While Brahim, al-Farraj and al-Awwad paid to have their homes connected to the electricity grid, the cables were recently stolen. They do not currently have the means to replace them. Solidarity Fields aims to pay to install new ones once they collect enough donations.

In 2012, Shahoud, who was born to an Alawite family, joined Tartus’ coordination committee, composed of local activists, which organized a handful of protests against the regime. After the war broke out, she started teaching displaced children whose studies were interrupted by the war.

For her, women are integral to what Solidarity Fields is working to achieve. “I try to make women rebel so that they have a role. They work more than men on the land but aren’t decision-makers,” she says.

“There must be women’s empowerment and psychological support for those who lost their husbands and have no financial support,” she adds. “However, they need a door before we can work on empowerment.”

In the meantime, al-Awwad, Brahim and al-Farraj are working hard to feed their families and make them feel at home. Like the seeds they have planted, they have put down roots. “If the state comes, we don’t dare leave,” Brahim says, with a hint of rebellion.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.