Amir, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, cowered as the armed men searched him for weapons they accused him of hiding in his scrubs. He insisted he had none, and they soon found he was telling the truth. Kneeling in a lobby of the Sweida National Hospital in southern Syria, his colleagues to either side of him, he raised his eyes and saw another colleague — a volunteer this time — descend the stairs. His name was Muhammad Bahsas, an engineer.

Some of the armed men were wearing military garb, while others donned the black attire of Syria’s government forces. Their eyes widened in recognition as they saw the surprised colleague. They hit him, enraged, and shot him. He fell to the ground, lifeless, as the gunshot echoed through the hospital corridors.

Some accounts say Bahsas was targeted after previously ignoring a gesture from Bedouin-aligned forces to stop, as he was helping injured people in the hospital. Others say he invoked the ire of the forces after rejecting their requests to come help their comrades, asking them to bring their injured to the hospital. Either way, the forces’ anger toward him paved the way to his death at their hands, surrounded by the people he was helping.

“Take this pig and throw him in the trash,” they ordered, gesturing at the corpse at their feet. The medical cadre rose, picking up their colleague, putting him where they’d gathered others who had died in the clashes.

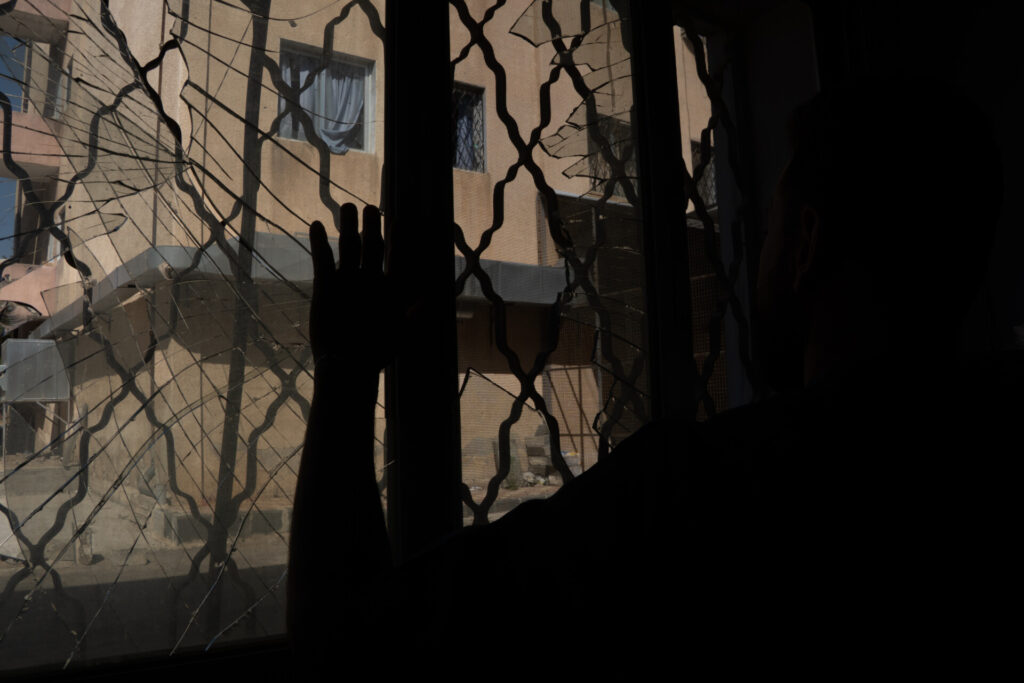

Amir lights up a cigarette as he narrates this story, which has been confirmed to me by other eyewitnesses. He doesn’t want to be photographed or have his identity revealed. He sits in an office and is constantly interrupted by the flurry of medical staff walking in. To his back is a shattered window.

“After they set us on the floor, one of them — not from the General Security, I think he was from a militia — was photographing us and talking to a person on the phone,” he says, aware that his face is now recognizable by the very men who murdered his colleague. From the tone of the conversation, he thinks documenting the cadre’s faces was part of the orders they were given.

The hospital’s compound is still littered with glass and bears all the markings of an area fresh out of conflict. There’s an ambulance parked in front of the emergency department with cracked windows. The tension in the air is palpable.

The saga of the Sweida National Hospital, caught between warring Druze and Bedouin-aligned forces in clashes in July, enduring gunfire, the murder of health care professionals and armed takeovers by competing militiamen, offers insight into the bloodletting that upended the fragile calm in the Druze-majority region. It is also a microcosm of how disinformation and propaganda fuel the anger that sustains sectarian and communal violence in post-Assad Syria, threatening the nation-building project that remains in its infancy.

In mid-July, the governorate of Sweida was the site of violent fighting between the local Druze majority, who are a minority in Syria overall, and neighboring Bedouin tribes. The government deployed its forces, ostensibly to maintain peace, but their incursion was perceived by the Druze as an invasion aimed at regaining control over Sweida.

Testimonies from hospital staff and patients indicate that, though the individuals who entered wore a mix of uniforms, a few of them wore the black shirt and pants usually donned by government forces. Amir tells me that the Islamic declaration of faith, or “shahada,” was stitched on most of them.

Bahaa, 27, whose name has also been changed to protect his identity, is a doctor at the hospital. He is soft-spoken and patient, and tells me how, starting on July 13, the hospital began to come under pressure with the number of injuries coming in. On the morning of July 14, “there was shelling on Sweida and, all day, the injuries didn’t stop coming in,” he says, adding that most of the wounded were civilians.

In the hospital wards, there were women and children, some of whom had been shot at while trying to flee, and others who’d been injured by shelling on their homes. Some were being fanned in the sweltering heat by relatives, while others were still in shock, barely processing what they had undergone.

“There were gunshot injuries, but their number was very low because they were trying to besiege Sweida with shelling and rockets.”

The next day, Bahaa says, General Security forces arrived at the hospital. The doctors “treated them normally like they would any other patient,” before they began coming into conflict with other patients in the hospital. According to media reports and people from Sweida, the opposing forces began to gain control over the hospital on July 14, after which the situation escalated massively.

Based on the testimonies I gathered, it appears that Bedouin-aligned gunmen found three snipers from their forces injured on the roof of the hospital — possibly having made their way there as their side took control of the building. They were brought down for treatment but began to come into conflict with other individuals in the Druze-majority city. According to Bahaa, there were some “Sweida factions present in the hospital,” but the staff didn’t know which factions they were from.

Hazem, a nurse at the hospital, explains that the facility was placed under guard by men from the community, whose fate he doesn’t know. How the armed men were able to arrive at the hospital is still a mystery to him.

“We don’t know how [they] were able to enter,” he says. He speculates that the men stationed for protection may have fled when threatened, or been killed.

Hazem adds that, based on his chats with colleagues two days later, the three men were taken into the “police station” of the hospital, usually used to hold people who were injured in ways that had a legal dimension, like car accidents. The station was farther away from the crowds of people, and taking the Bedouin-aligned forces there was a way to defuse tensions and potentially avoid fighting within the hospital walls. He says two of the men were not injured heavily, though one was and ended up dying.

I was not able to confirm who fired the first bullet but, based on the conversations I’ve had, I do know that these two individuals were shooting and being met with return fire. This exchange of bullets apparently lasted over two hours.

Yet the heavy fighting didn’t only hurt those carrying arms. Few escaped the wrath of the communal violence. The station was farther away from the emergency department, but the department was not far enough for it to escape the crossfire.

“There were clashes here in the hospital, in the middle of the emergency department,” says Bahaa.

Those I spoke to at the hospital framed the killing as a deliberate assault on unarmed civilians. I was unable to confirm whether this was indeed the case, whether the civilians were unfortunately caught in the crossfire, or whether the truth is somewhere in the middle.

“There were tanks around the hospital firing at it. We were besieged on the second and third floor[s],” Bahaa says, explaining the dire conditions in which they were operating, with the hospital witnessing clashes within and around it.

Apart from the exchange of fire, the hospital was witness to myriad violations. There was the public execution of a volunteer, and forces also seized the phones of medical teams and patients. At one point, Amir says that, along with his colleague, he was forced to ascend to the top floors of the hospital at gunpoint, as gunmen inspected the different departments, searching for weapons or people hiding. Blood was pooled on the floors. He says the gunmen demanded to know whether it was Druze blood, and asked hospital staff why they were treating Druze patients.

“We said, ‘We are a hospital, we treat everyone,’ and they said, ‘No, Druze blood shouldn’t be treated,’” Bahaa explains.

Hazem wasn’t present at the hospital during the initial days of conflict but arrived at a scene of absolute chaos and destruction on July 18. As he recounts to me the events of that day, his convictions are strong, but his mood oddly upbeat — perhaps a coping mechanism for all he’s seen. He tells me that his colleagues filled him in on the details of events from the preceding days. With both sides armed, tensions were sky-high. He says the head of the emergency department, Nabil Sehnawi, kept insisting to keep the hospital out of the conflict, to no avail.

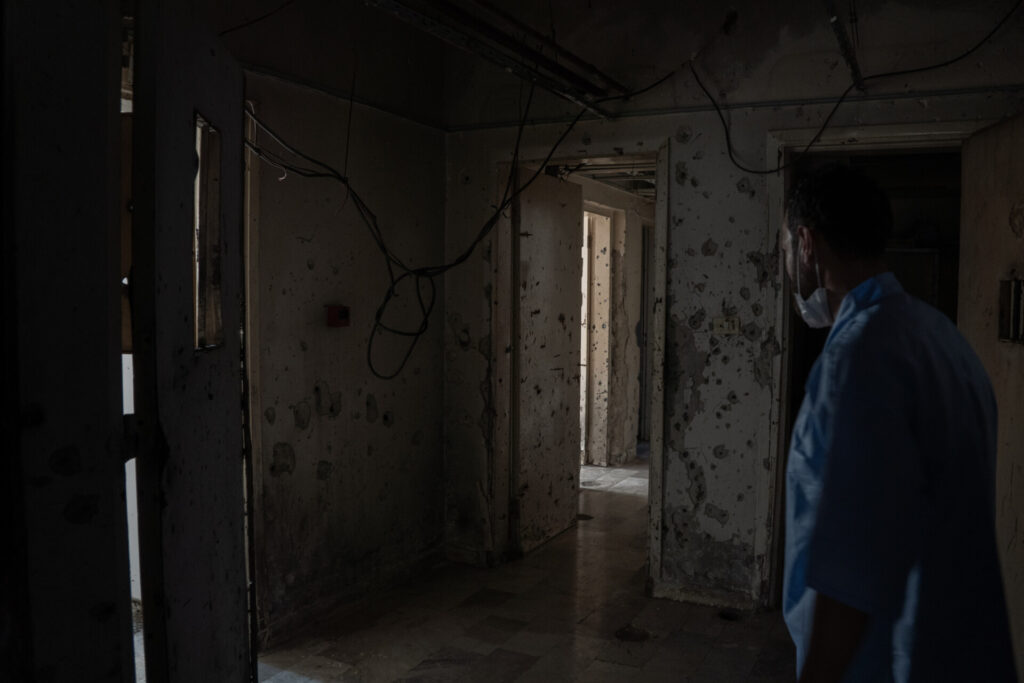

The walls, dotted with bullet holes, are a testimony to these clashes. There is a dissonance between Hazem’s scrubs, symbolic of healing and humanitarian work, and the rashness of the actions that created these indentations in the walls. One of the hospital beds was still bloodstained, the massive spill barely cleaned up. With the large number of civilian casualties, the medical facility was in urgent need of more hands.

“My cousin talked to me, saying, ‘Hazem, come, don’t go with the guys who went to the front line — come to the hospital because we need you.’”

Hazem has been a nurse since 2017 but also keeps a gun at home for self-defense. Like many others in Sweida, he picked up arms in this latest round of conflict, to help protect his family and community.

Widely shared videos on social media show bodies collected en masse in the courtyard of the hospital. In the first days of the conflict, Sweida was largely inaccessible to journalists. On July 18, I received videos from a Sweida resident who filmed them himself at the hospital. Bloodied corpses were strewn all over the hospital compound as well as inside its corridors. The videos weren’t easy to watch. My contact mutters, “Oh, God,” as he films the slightly blackened bodies soaked in blood, his voice rising with each corpse he passes.

When I visited the hospital on July 23, the bodies had been taken away, but the air still bore the strong odor of death — a smell that’s hard to describe but even harder to get rid of. Amir insisted I wear two surgical masks and pulled gloves onto my hands.

“The bodies had decomposed, there were some with worms crawling out of them, and they were emanating bacteria. And the smell was so disturbing and pungent,” he says, explaining how the hospital staff were now worried about infections.

The backyard had been cleared up but not cleaned. Pools of blood glistened in the afternoon sun, with an odd shoe, bullet or set of discarded scrubs dotting the ground. The blood was still wet and stained the bottom of my jeans.

A few yards away, humanitarian aid convoys lined up to deliver supplies to the hospital. The bright red on the Syrian Arab Red Crescent trucks, which waited for days to be let into Sweida, and the dark red of the days-old blood stood just a few yards away from each other.

When I went back into the hospital building and started to pull off my gloves, the nurses and volunteers offered me disinfectant solution to scrub my hands.

Right outside the entrance of the hospital was a pile of sand. Upon closer inspection, I could see that it was merely a cover for yet another corpse, a remnant of the fighting. A black toe stuck out of the white of the sand. The stench of death permeated the sidewalk. People walked past it, perhaps unaware of their proximity to death.

The story of Sweida National Hospital reflects the on-ground complexities of the Druze-Bedouin conflicts and the nature of the Syrian government’s involvement. Amir explains how multiple groups of Bedouin-aligned forces entered the hospital, some “more understanding” than others.

“We told the group, ‘We’re hospital staff, we have nothing to do with all this.’ And [one of them] said, ‘I get that, but the others don’t.’”

Faced with what was widely perceived as the threat of extermination, the public in Sweida has largely shifted to a defensive stance, wanting to protect their community against an oppressor. Men from all walks of life, who had never lifted a weapon before, pulled out hunting rifles and personal weapons to help defend their community.

After my visit to the hospital and discussions with other reporters who attempted to get to the bottom of how it turned into an area of active fighting, what is clear is that the story is much more complex than initially shown on social media. Rather than a one-sided massacre of civilians, it is clear the fighting was two-directional, even if couched in the dynamic of aggressor versus defender. The issue of Sweida remains heavily polarized, with those once open to dialogue with the government now much more hesitant to engage with the central authorities. Whether they are hospital workers or not, all inhabitants of Sweida share this sense of betrayal and of a need to fight for survival.

According to international humanitarian law (IHL), hospitals are given special protection and must not be attacked or dragged into conflict. Forces from the opposing parties were entering the Sweida National Hospital, threatening medical staff, confiscating their phones and looking for weapons.

IHL states that hospitals can lose their protection status in the case of acts “harmful to the enemy” but doesn’t specify what that means. It does, however, exclude from the definition “carrying or using of individual light weapons in self-defense or defense of wounded and sick; armed guarding of a medical facility; or the presence in a medical facility of sick or wounded combatants no longer taking part in hostilities.”

Over the course of more than 13 years of civil war in Syria, medical facilities were attacked over 600 times. With the overthrow of the Bashar al-Assad regime in December, there was brief hope for peace in the country. Yet the scenes of horror in the hospital corridors and compound evoke the painful memories of attacks on health care facilities still fresh in the minds of medical workers and patients.

By July 25, the unidentified bodies from the hospitals had been taken to a mass grave farther out from Sweida. Basel Yaser Abu Saab drove the truck that carried those bodies. The road leading up to the grave is still stained with the maroon of blood, darkening with time.

Abu Saab explains how the hospital documented each body and assigned it a number for identification. The gravediggers were asked to bury the bodies such that each segment of the mass grave corresponded to certain numbers.

“If a relative says they want to exhume [their loved one], we can’t say no,” he says, wincing a little bit at the thought.

There’s an odd calm to this part of Sweida — less armed presence, fewer real indications of what the city has witnessed. I see that the mud of the grave is darker than the soil surrounding it, still fresh from being moved. Between the two raised mounds of soil that mark two ends of the grave is about 20 yards, a temporary home for those it holds. Abu Saab says they buried 149 unidentified people.

His voice rises in aggravation as he talks about the things he saw.

“Some of the people who fired the shots are cold-blooded,” he says. “Some people had been there for 10 days, the stench …” He can’t finish his sentence.

The identified victims of the conflict are at rest, but the living are still processing the horrors they lived within the walls of what was supposed to be a safe area, one for healing and no more.

“The worst thing I saw was dead kids, women and old people who did nothing. Here in Sweida we are a family, so it is very upsetting to see people who lost their arms, people beheaded,” Amir says. “If the killing was between people carrying weapons, things are OK, but you killed [old people and children].”

He stares out of a window, its glass shattered, like the hopes for peace in Sweida.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.