In the summer of 2024, José Segura Briones boarded a plane in Malabo, the capital of the West African nation of Equatorial Guinea, where he had lived and worked for decades. He was headed to the Spanish capital, Madrid, to join a few dozen Equatorial Guineans in marking the second anniversary of the self-proclaimed Independent Republic of Annobon — the tiny, remote island in the Atlantic on which they were born and which they have not visited for years. It was a modest affair, but it echoed 2,600 miles away in Malabo.

A few days after the independence day celebration, a series of raids by Equatorial Guinean police resulted in the arrest of 42 Annobonese in different parts of the country. Segura’s wife, Estela Alfaro Aracil, was among them. She is now being held in the notorious Black Beach prison, one of the worst in Africa. Their son is alone in Malabo and Segura Briones is stuck, jobless, in Spain. As he sits sipping his coffee in a bar across from Madrid’s train station, he muses that Spain is just the latest country he didn’t choose for himself. He, like many Annobonese, feels the decolonization of Africa from European nations didn’t free them — it just gave them a new colonial overlord.

In the cafeteria next to him sit Orlando Cartagena Lagar and Gutïn Bahê Tongalan, Annobon’s self-styled president and minister of information, respectively. Both have been in exile in Spain for years. They are the two main leaders of Ambo Legadu (“Free Annobon”), the movement that declared the independence of the island as a way to denounce the economic underdevelopment, isolation and political repression they say they have been suffering for 46 years under the regime of Teodoro Obiang — the world’s longest-serving dictator, as well as one of its cruelest — and for decades before, as well.

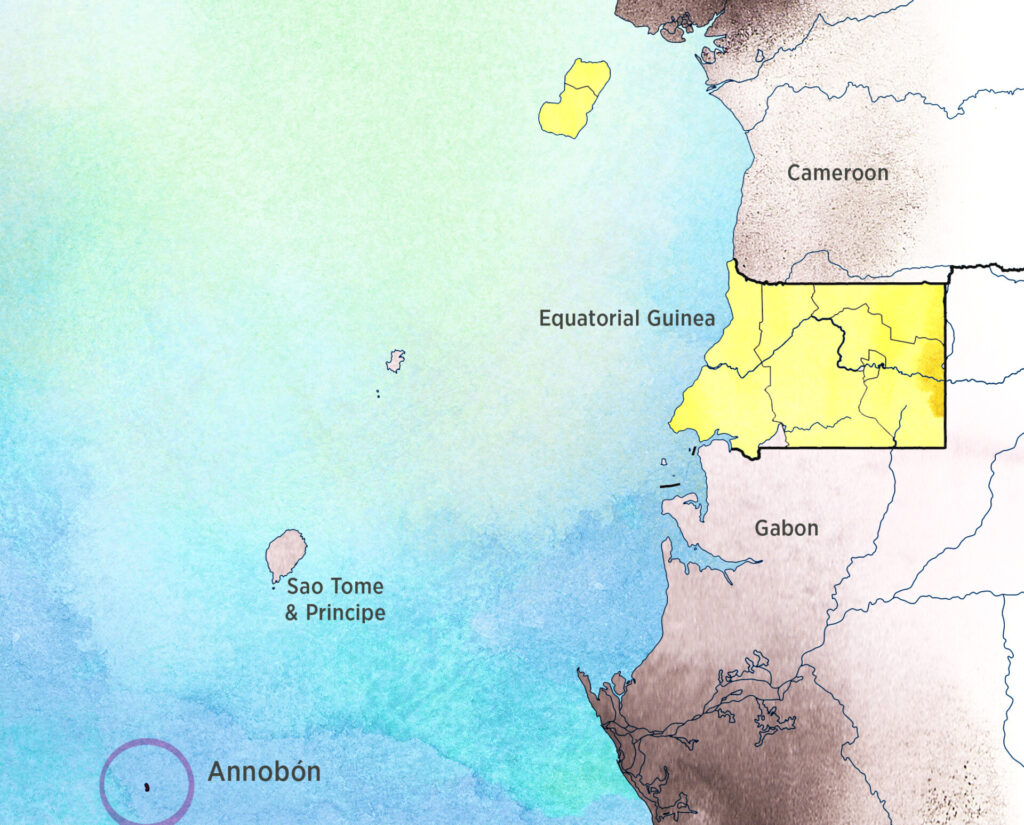

Annobon itself is a rocky atoll, just 45 square miles in size, perched in the Atlantic Ocean about 200 miles from the coast of Gabon, in West Africa, and some 400 miles from Equatorial Guinea’s capital on the island of Bioko. The island was uninhabited when it was discovered by Portuguese sailors on New Year’s Day (“ano bom” in Portuguese, hence the name) in 1471. Today, it is home to between 3,000 and 5,000 people. Benita Sampedro, a professor of Spanish colonial studies at Hofstra University, stresses that the Annobonese are not an ethnic group “but a cultural group made up of populations of different origins that arrived on the island,” many of them as slaves brought from different parts of the continent.

Portugal took little interest in the island, abandoning its foothold there in the 18th century. It passed into Spanish hands in 1778, though not a single Spaniard set foot on the island until a century later, creating a period of de facto decolonization, during which the Annobonese ruled themselves for much of the 18th and 19th centuries. The historian and anthropologist Valerie de Wulf explains that Annobon was “one of the first territories in Africa to be decolonized, a century before Haiti, and where slavery disappeared earlier.”

As the Annobonese novelist Juan Tomás Ávila Laurel writes, “For years they remained alone, without even an evil power willing to call them servants.”

In 1968, when the Spanish pulled out of West Africa, “the logical thing,” according to de Wulf, who has written two volumes on Annobon and its inhabitants, would have been for the island to become part of the Republic of Sao Tome and Principe, the collection of islands that sits between Annobon and Bioko, where a Creole language derived from Portuguese is also spoken.

But the Equatorial Guinea Independence Conference, convened by the Francisco Franco dictatorship with only one Annobonese representative, did not envisage any other territorial solution for the remote island than joining it to Spain’s other former colonial holding. Ambo Legadu says that the process imposed on Annobon membership of a state — Equatorial Guinea — with which it has nothing in common. Tensions between the Annobonese and the ethnic Fang majority in Equatorial Guinea are heated. Ambo Legadu argues that the island has received nothing but misery and violence from the Malabo authorities. On the island, the hatred for the Fang is intense and often spills beyond the confines of nationalism.

“Spanish colonization was good for no one,” Cartagena says, “but it is better to be a colony of Spain than to be slaves of the savages who kill us and occupy our land.”

Cartagena, Segura and Tongalan are old enough to remember the worst of the early years after decolonization. Equatorial Guinea’s interest in the island was almost solely territorial — its far-flung location meant the country’s territorial waters were expanded in the lucrative Gulf of Guinea, where oil is abundant — and few resources were ever put into the island. When successive cholera and measles epidemics hit the island shortly after independence, the dictator Francisco Macias decided to isolate Annobon and block health care to take revenge on the islanders for not voting for him in the first presidential elections. “We are the survivors of what killed many children our age,” Cartagena says.

In 1976, a boatload of soldiers arrived on the island to deport all the men who were fit to work on the mainland’s cocoa farms. Segura was 16 years old at the time and was forcibly put on the boat to be taken to Rio Muni, the landlocked continental part of the country, along with hundreds of his neighbors.

Segura says his story is a microcosm of how the Equatorial Guinean regime sees Annobon: as a source of resources — material or human — that requires no investment in return. The only presence the state has on the island is a military contingent. The education system does not go beyond elementary level. The medical infrastructure is so feeble that anyone with a moderately serious injury or ailment has to be evacuated from the island for treatment. There are problems with water sanitation and food shortages. Telecommunications are very precarious and there is no regular transport linking the island to the mainland or nearby archipelagos. The Annobonese cannot renew their identity cards on the island. Yet according to Equatorial Guinea’s press office in Madrid, “The situation on the island is completely normal.”

Tutu Alicante, an Annobonese jurist and founder of the human rights organization EG Justice, has long called out the Obiang administration for the abuses present in that normality. In return, the dictator has labeled him a “traitorous enemy of the homeland.”

Freedom House considers Equatorial Guinea “not free,” with only 5 out of 100 points for political rights and civil liberties. Alicante says that human rights violations are a constant. “Equatorial Guinea is not a dictatorship, but a mafia in which a capo decides everything.”

From his home in the United States, where he lives in exile, he tells New Lines: “It is very difficult to survive on the island because it is a territory that has been abandoned by a policy that centralizes everything in Malabo. In Equatorial Guinea, there is Fang hegemony, and all minorities are marginalized. That’s why most of the Annobonese have to move to Malabo.”

For the Equatorial Guinean government and its clientelistic networks, the island is just another asset for their business. Within the great corruption theme park that the Obiang family has turned Equatorial Guinea into — it ranks 173rd out of 180 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index — Annobon is one of the most opaque enclaves, and one of the most conducive to corruption. The 42 people detained during the summer of 2024 were arrested in connection with their opposition to real estate and extractive projects that the government is promoting on the island, together with the Moroccan construction company Somagec. “Our house in Annobon was damaged due to the use of explosives in the construction work,” Segura says, “and to talk about it in Guinea is politics.”

The projects against which the people of Annobon have rebelled are often the perfect alibi for bribery, money laundering and illicit enrichment. Proof of this is the tuna processing plant that a Spanish entrepreneur is allegedly building on the island in exchange for more than 2 million euros. The work has barely progressed after eight years, and the man in question was arrested in Spain last summer on charges of corruption, money laundering and forgery.

In a tiny territory like Annobon, where the balance between available resources and population pressure is always on the verge of collapse, conflicts over land rights and use regularly cause clashes between islanders and the authorities. At the beginning of April, a state-sponsored news outlet published a piece warning of “the dangers of plantations in the airport environment in Annobon.” For the dissidents, the danger was not from the incoming planes but from the imminence of a new round of land expropriations that the warning silently signaled.

Despite so many affronts, not all Annobonese believe that the solution to their problems is independence. Alicante believes in a democratic Equatorial Guinea in which all ethnic groups can live together, “because the difference between a Fang and an Annobonese is no greater than that between a Franco-Swiss or an Italo-Swiss.” Ávila Laurel would support a quick and painless hypothetical independence, but adds that the island could not realistically support itself and the separatist adventure would most likely only bring “more suffering and repression for the people of Annobon.” The virulent punishment the island suffered last summer seems to support his thesis.

The regime’s excuse for keeping the detainees in prison, almost a year on, is that they finance the separatist movement or sympathize with it. Aitor Martínez Jiménez, the Spanish lawyer who represents Equatorial Guinean dissidents against the government in other cases, has filed a complaint with the U.N. Working Group on Arbitrary Detention to denounce the “absolute legal neglect” of the detained Annobonese.

Back in the cafe in Madrid, Cartagena, the president of the tiny and remote Republic of Annobon, which is not recognized by any state, unzips his backpack, removes a small wooden stool and places it on the table. It is a “kiskabelu,” “where our grandparents told stories, our mothers distributed the food and where everyone sits to debate and solve their problems,” in a form of democracy that “is centuries old in Annobon.”

He is hoping to restore that freedom and democratic spirit that the Annobonese enjoyed as a result of the failure of the colonial powers, when, according to the historian Baltasar Fra-Molinero, Annobon was for almost two centuries “the only territory in West Africa to enjoy a nonwhite local government composed of a council elected by the population.” In the years when the Portuguese and Spanish were absent, the Vidjil, a kind of parliament formed by the island’s council of elders, was the ruling body. Cartagena wants to see a similar system reemerge.

José Segura is now 66 years old and has lived under an imposed colonial regime and two dictatorships in a country he does not feel is his own. If he could choose a country, it would be a floating republic on the islet of volcanic rock in the middle of the Atlantic where he was born. But for the moment, the restoration of the Black Republic of Annobon is little more than a dream being plotted in a cafeteria in the centre of Madrid.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.