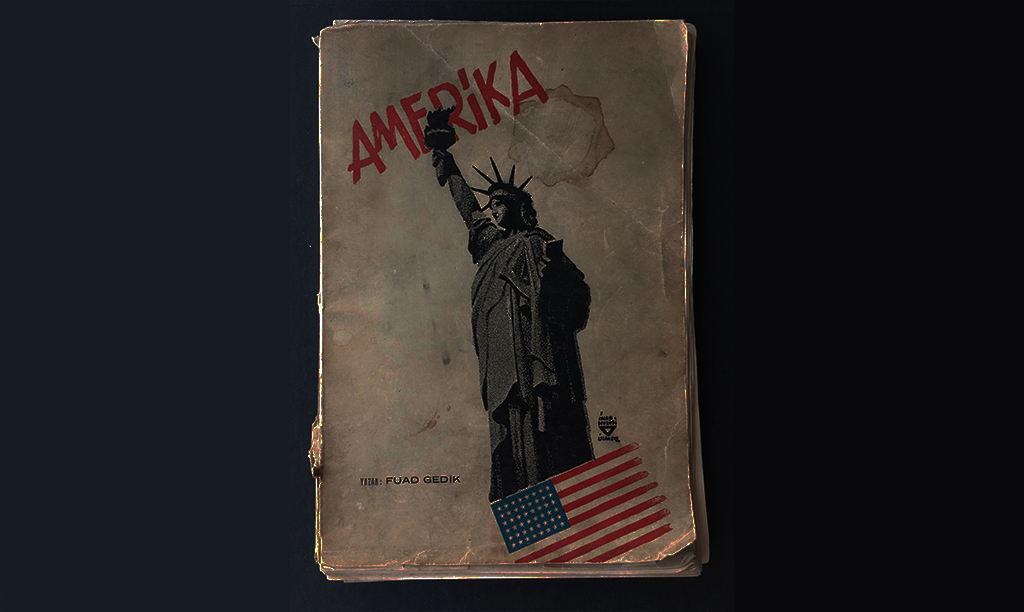

Fuad Gedik was a Turkish legal scholar who recounted his 1947 trip to study the American criminal justice system in a book simply titled “America.” He visited New York and then Washington, a city so dull by comparison the Turkish Embassy staff had taken to calling it “Ankara.” Among other things, Gedik was fascinated by Italian Americans, American women, and the possibilities of fingerprint analysis.

One afternoon in Manhattan, he walked into an ice cream parlor and heard the shopkeepers cursing each other in Turkish. “God damn, are you an infidel?” one shouted. It turned out the men were Jewish immigrants from Gallipoli. One was eager to show Gedik family photos, and when Gedik left, he refused to take any money from him. Gedik wrote that when he insisted on paying, the shopkeeper “got angry, just like a Turk.”

Of the Armenians he met, Gedik observed that “they live just like they would in Istanbul or Anatolia. … all of them, even the ones that don’t like us.” They eat Turkish food and “instead of Martinis and Manhattans, they drink bootleg raki.” “Most of them,” he concluded, including the ones who have been successful in America, “are unhappy here and miss their lives in Turkey.” As evidence of this, he described meeting a woman named Meryam who introduced herself to him as a Turk, then cried when his cab pulled away.

There was also an “elderly, good-hearted man” named Artin. “Ah, Galata,” Artin declared as they sat in Midtown, “it alone puts this whole city to shame.” “Those were the days, my God. Oh, those were the days.” When Gedik said farewell to Artin and his wife upon leaving New York, Artin began to weep, even though he had promised not to. His lip curled and hot tears began to flow. “My bones will be buried here,” he cried.

The 1940s and ’50s were a golden age for Turkish travel writing. A growing number of Turkish visitors came to the United States, often sent by Ankara for technical training or invited by Washington for cultural exchange. These were boom years for the Turkish publishing industry, and visitors invariably wrote up their experiences for a hungry audience in books and newspaper columns, with titles like “Letters from America.”

Arriving in America, usually New York, Turkish travelers quickly began trying to make sense of what they found. Their commentary veered from trite to profound and from witty to completely unexpected. They included the most minute observations about daily life as well as broad philosophical reflections on the nature of the American character. They were amazed by the cheap price of food and reflected on the sincerity of the people they encountered. One author remarked that the cars crawling along the avenues of New York City looked from above “like a herd of turtles.” Their language, even the varied transliteration, hints at how new it all was. Were the buildings “Skyskrapers,” “Sky Cruppers,” “grattacielo,” from Italian, or simply, in Turkish, “Sky Piercers”?

Like everyone seeing a new country for the first time, the authors of these mid-century travel accounts found much to marvel at and much to criticize. They praised some American customs, like barbecues and mobile libraries. They were taken aback by others, like Americans’ love of watching football and “eating ice cream together with their food.” Some things just seemed tacky, like “wearing white suede sports shirts alongside silk ties with pictures of roosters, peacocks, and naked women on them.” The subject of racism was inescapable. Many visitors harshly condemned the ugly prejudice they observed. Others, citing their experiences in Harlem or the Ottoman army, seemed suspiciously sympathetic. Not infrequently, authors would comment critically on racism and make racist comments within the course of a single page.

Read today, a particularly striking aspect of these accounts is the many warm interactions they document with non-Muslim immigrants who had come to America from Ottoman lands. Turkish travelers during this period consistently described being greeted enthusiastically, often in Turkish, by the many formerly Ottoman Greeks, Jews, and Armenians they met.

As recounted by the Turkish participants, these interactions were touching and tragic by turns. The immigrants’ own, unfiltered views are absent, of course. Yet, while the majority of them had already been in America for several decades, their memories, both nostalgic and painful, were still fresh. Particularly for Armenians who fled the 1915 genocide, the history of how they left Turkey hung heavily over these conversations. In some accounts, Turkish visitors give the distinctly uncomfortable impression that they see these exiles’ homesickness and kindness as a straightforward testament to the charm, graciousness, or success of the country that drove them out.

Conversing together in mid-century America, Armenian immigrants and Turkish travelers were moved to tears by memories of their shared homeland. But also, explicitly or not, they faced questions about who had been allowed to stay and who could never go home. Taken together, these accounts puncture nationalist myths about age-old and undying hatreds. But they also push back against sentimental countermyths and remind us that political trauma doesn’t disappear over a shared drink, whether it’s raki or Coca-Cola.

I came across these vignettes in different contexts while conducting research on early Cold War U.S.-Turkish relations. In subtle ways, they seemed to both confirm and question aspects of the conflicting personal and political narratives that Turkish and Armenian American colleagues have shared with me over the years.

In 1939, a Turkish engineer named Kemal Sünnetçioğlu took a government-sponsored trip to New York City to study the mechanical exhibits at the world’s fair. According to his account — “1939 World’s Fair Travel Memoirs” — he went about his work quite earnestly.

One day, near Macy’s, Sünnetçioğlu saw a sign for an Armenian restaurant called Baba Nisan’s. Curious to learn more about these people who had been “slandering” his country and hoping to find the food he missed from home, Sünnetçioğlu stopped in.

The staff, he reported, were delighted to find out he was Turkish and inundated him with questions. He was amazed to discover they still spoke Turkish among themselves. “The influence of Turkish culture,” he observed, “still continued,” and these men “still burned with longing for their homeland.”

Sünnetçioğlu immediately went on to explain that the Armenians in Baba Nisan’s exemplified the fate that awaits those who are seduced by foreign schemes. Armenians had been given the duty of stabbing their country in the back and failed. Some of them were “cleansed” and some escaped. Now, despite knowing that their sins would never be forgiven, these men waited for news from their native land and asked him “the most random things” about it.

According to Sünnetçioğlu, they did not want to believe the great reforms Turkey had undergone since they left, and they were shocked to find out he was staying in a first-class hotel. That afternoon, he had a similar experience with an Armenian barber on Fifth Avenue. Like the restaurateurs, the barber bombarded him with questions and was amazed by his answers. The man wouldn’t let Sünnetçioğlu leave, insisted he return, and refused payment for his shave.

Later, Sünnetçioğlu encountered an Armenian waiter in his hotel restaurant. George was from Urfa and served him with impeccable politeness at every meal, even anticipating the dishes he wanted. Witnessing this, Sünnetçioğlu reflected on why the Armenians who fled Turkey all showed Turks such esteem: “Realizing that Turkey is not the old Ottoman Empire and has achieved such high status among nations, they now must kiss the hand they could not bite.”

Dr. Perihan Çambel traveled to St. Louis in 1949 as a Turkish delegate to the fourth International Congress of the American Cancer Society. She recorded her experiences in a column titled “My Week,” for Turkey’s Women’s Newspaper.

One Tuesday evening, she attended a dinner meeting of the St. Louis Female Doctors’ Club at a restaurant run by a Bulgarian man named Johnoff. At some point in the evening, Johnoff pulled up a chair next to her and, after saying hello in Turkish, began recounting his life in Thrace 45 years earlier. He offered her sweet wine and yogurt and recalled that the two Turkish officers who once visited his restaurant in Bulgaria had been upstanding men. “If only I could go to Istanbul before I die,” he said, with his eyes watering.

The Americans, Çambel reported, were shocked to see a Bulgarian showing such “respect and hospitality” to a Turk. She called the other Turkish doctor in town to tell him about Johnoff. But, of course, the two already played backgammon together. Just the other day Johnoff had sent him a plate of stuffed cabbage leaves at the hospital.

Johnoff’s story led Çambel to tell her readers about a man named Armenian Joseph, one of her colleague’s cleaners, who had lost his parents in an “Armenian massacre.” She quoted Joseph as saying: “Ah, if only they’d give me permission I’d return. Those who are alive today had nothing to do with that business. I bear no hatred toward them. I want to return to my country and spend my retirement there.” What a good advertisement it would be for our democracy, Çambel remarked, if Turkey recognized the right of these people to return to their homeland.

Later, with her fellow Turkish doctor, she visited the shop of an Armenian cleaner named Hrant. Hrant offered them beer and Coca-Cola and revealed that his abiding wish in life was to go back to Turkey. Çambel recounted that Hrant’s mother and father were killed “in the Armenian bloodletting” but “in spite of this, he welcomes all the Turks who come to St. Louis in his shop.” “In his speech, in his demeanor, Hrant is no different from a Turk from Erzurum, or more precisely Kiğı.” Commenting on Hrant’s feelings toward Turks, Çambel wrote: “Every year from time to time he sends 25 or 100 dollars to the Turkish family that saved his life by hiding him in their house. … only every so often, he would repeat [to us] ‘but you killed my mother and father.’” “However,” she concluded “Hrant was ready to forget this,” and she, for her part, “wanted to help him forget it.”

As a young journalist, Bülent Ecevit, later Turkey’s prime minister, spent four months working at a newspaper in Winston-Salem as part of a State Department-sponsored exchange program. At the newspaper office one day, he was shocked to answer the phone and hear a voice speaking to him in Turkish. The woman on the phone said she was from Istanbul: “I came here 35 years ago. I’m dying to see a Turkish face, to speak with a Turk. Will you come for a cup of coffee?”

Meeting outside the Winston-Salem Journal’s office, they recognized each other immediately: “Who could she be but Mrs. Kasparian? Who could I be but the Turkish journalist at the Journal.” Ecevit wrote that when he entered her house, “America remained outside.” A certain “Istanbulite sensibility” had even crept into the American furniture. As she served Ecevit, Mrs. Kasparian lamented that though she was always drinking Turkish coffee, “it lost its taste without someone from Turkey to drink it with.”

Mrs. Kasparian had married an Armenian tobacco expert and moved to the world’s tobacco capital, Winston-Salem. She now lived there alone with her teenage daughter. She couldn’t get used to her daughter socializing as freely as American girls, but what upset her even more was when her daughter said she was American and didn’t want to return to Turkey.

“What can the poor girl know?” Mrs. Kasparian asked, “Without seeing Turkey, she can’t understand what she’s deprived of.” Looking out the window, she continued, “You call this the sun? You call this the sky? You call the peaches they eat here peaches, the vegetables vegetables? If you saw the sea in Istanbul, tasted the life in Istanbul … If you took the ferry from Kadikoy to the bridge one morning, could you ever live here?”

The daughter smiled as she listened and turned to Ecevit: “Look, ever since I can remember, my mother has been saying this, but I don’t believe it. The sun is this sun everywhere, the sky is this sky everywhere. Is it not?”

“I was about to say, ‘It is Not!’” Ecevit wrote, “but I didn’t say anything. I just looked at her mother. Our eyes were full of tears.”