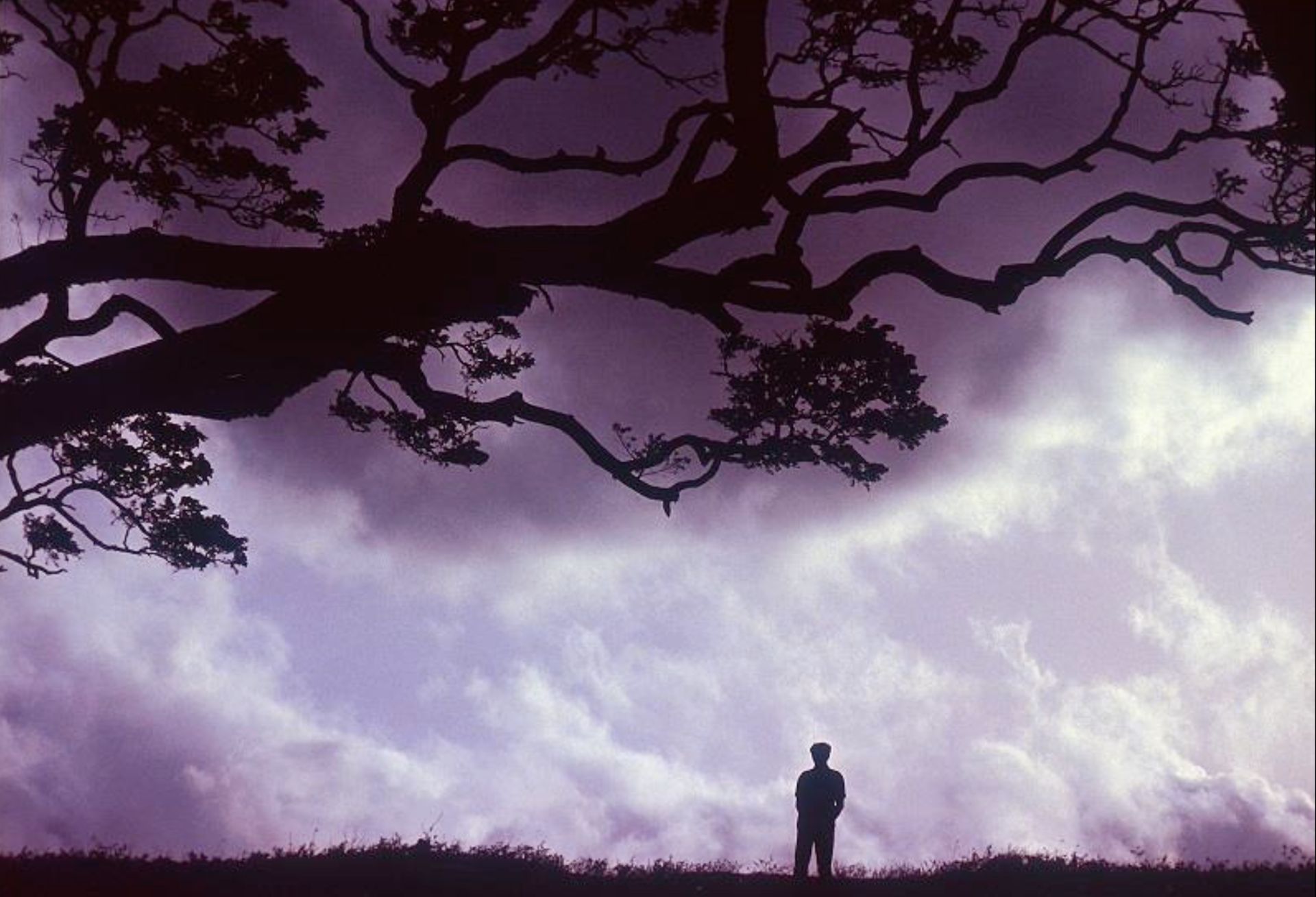

The refugees came quietly, careful not to disturb the world they were leaving or the ghosts already waiting on the other shore. They clutched bundles; bread or babies, it was hard to tell. The men carried only fatigue. The children’s eyes were large, hollowed by sights they would never describe. They had abandoned their homes, and soon even the names of those places would vanish. There were no declarations, no banners, only boats: small, splintering craft rowed through the narrow waters between Jaffna and the forgotten villages of Tamil Nadu. The Palk Strait is not wide, yet on those nights it seemed endless.

For 26 years, from 1983 to 2009, Sri Lanka had been the stage for a long annihilation, between a Sinhalese-majority state and the Tamil rebels of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). What began as grievance hardened into ideology, then into siege. The civil war was not the longest of our age, nor the largest, yet few conflicts have left such a dense and divided silence in their wake.

And that is how it began for me. Not with the noise of artillery, but with the silence of oars dipping into black water. The Tamil refugees crouched on the planks, pressed shoulder to shoulder, whispering prayers, exhaling fear. No one wept; there was no point. I sat where they sat, smelled the same fear, and when the wind shifted, the same blood. The sea carried more than the living.

From the boats I drifted into the camps, and from the camps into the forests. At first I moved with a ragged constellation of groups: ideologues with unread manifestos, boys with slogans but no weapons, exiles rehearsing a return already lost. I watched their dreams rot in the heat until they vanished, absorbed or destroyed, leaving only the Tigers. And so, in time, I moved with the Tigers, exclusively. They, at least, had mastered survival. Years later, when the guns finally fell silent at Nandikadal Lagoon in May 2009 and the state proclaimed victory, nearly 100,000 had been killed. Many more disappeared into euphemisms: “operations,” “counterinsurgency,” “rehabilitation,” “relocation,” “missing in action.” Villages vanished, cities were shelled and generations grew knowing only suspicion. The world looked away, mistaking exhaustion for peace.

Beneath the architecture of reconciliation, the war persisted, in memory, in language and in the policing of grief. The victors built monuments; the bereaved were smothered in silence. The question of truth, always deferred, has since returned from the ground itself.

In Chemmani, a small town near Jaffna, the cultural heart of the Tamil Tigers, the earth stirs. The soil, long compacted by denial, yields its dead, with bones rising where silence once held dominion: a woman’s anklet, a child’s button, the curved glass of a bottle meant for a hand that never grew. The accidental discovery last summer of a new mass grave with 19 bodies, including three infants, only confirms what was always known, what survivors whispered through the years. Each exhumation reopens what peace concealed.

This is not closure, but history refusing burial. The graves are not archives, but indictments, an argument against forgetting. What was buried did not decay. It waited, stubborn as guilt, for its unearthing. The war never ended; it merely changed depth. Beneath asphalt and rhetoric lies a dark seam the living agree not to see. What tribunals could not name, the soil now mutters — breaking through the language of reconciliation, reminding us that amnesty without truth is merely postponement.

Like many who arrived with notebooks or cameras, I told myself I was bearing witness. I stayed too long to remain untouched, and not long enough to claim anything other than fragments. And fragments rarely tell you what they mean. They stay with you, not as images, but as questions. The war scattered stories as wind scatters ash; what remains cannot be retold, only inhaled. What endures is no ledger of events but a fogged window, smudged by distance, politics, betrayal and shame. The writing that followed, from generals, diplomats and journalists, was too tidy. It either justified or avoided. Some thundered. Some whispered. Each attempt to narrate faltered. Most evaded the truth. But what refuses to be written is often where the war still lives.

Chemmani is not a revelation. It was here in 1996 that the body of Krishanthi Kumaraswamy, the schoolgirl who had been gang-raped by members of the Sri Lankan Army, was recovered along with those of her mother, brother and a family friend. Lance Cpl. Somaratne Rajapakse, who was found guilty of the rape and murder, alleged at his trial that up to 400 people had been buried in mass graves in Chemmani. A 2017 Amnesty International report estimated that up to 100,000 people disappeared in Sri Lanka during the war.

The same earth that once swallowed the disappeared now exhales them. From that disturbed earth, I ask what happens when the instruments of truth — journalism, history, photography — reach their limits. When what can be verified falters at the threshold of what must be imagined, literature becomes not escape, but evidence. The work of writing is not to conclude the war, but to chronicle its persistence, quietly, beneath our feet.

There are things I witnessed that I have not written. Others I could not. And still others that remain untold because they cannot yet be risked. Some I wrote before I understood what I had seen. That uncertainty remains. Wars like this one do not end when the shooting stops. They continue in stories, in silences, in the faint, terrible suspicion that no one ever saw the whole of them. Sri Lanka’s war, like photographs, still develops in the dark.

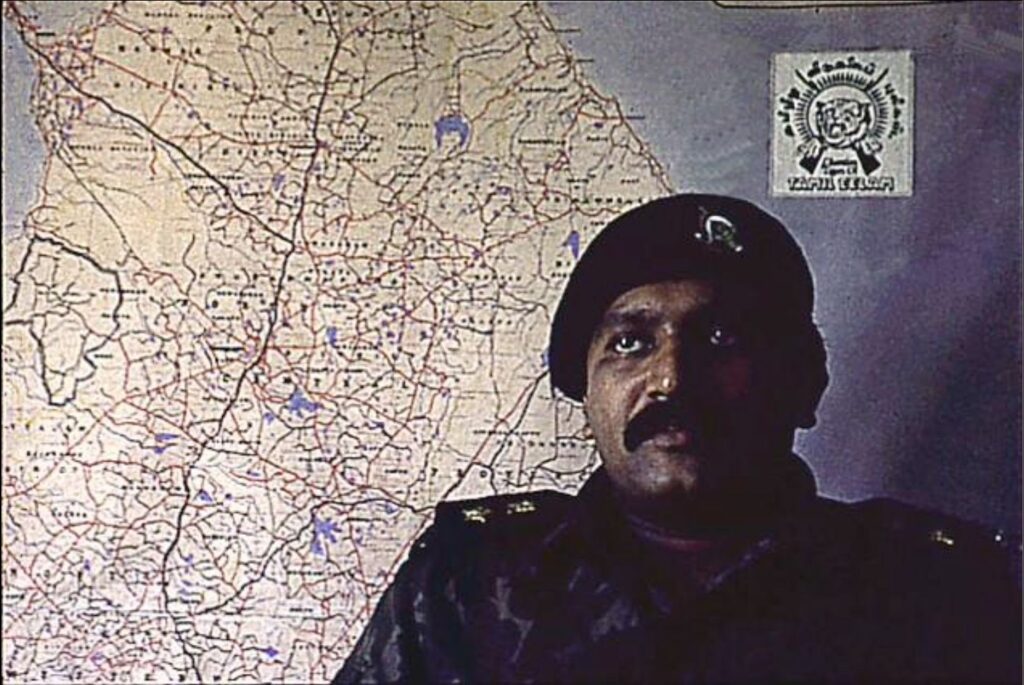

On 18 May 2009, the Sri Lankan government declared an end to the war, which in its final phase killed up to 40,000. Thousands of civilians were killed and many more displaced. The war ended not in triumph but in something closer to abandonment. No treaty was signed, no surrender declared. At Nandikadal Lagoon, where the last bodies fell, the final image was not a flag raised in victory but a corpse in the mud. He died barefoot, bloated not just by water but by history. Velupillai Prabhakaran, architect of both fear and fidelity, his mustache, once iconic, reduced now to hair on a corpse. Around him, the last circle of bodies. And yet he remained, not as martyr, not as monster, but as something more complicated: the liberator who caged his people, the strategist who misread the endgame, the revolutionary who outlasted the revolution. The cause that bore his name burned beside him. Truth, too, was exiled: driven from the dispatch and buried in metaphor. Eelam — the independent Tamil state to which he aspired — was a dream he dared, and drowned. In the cracked mirror of memory, he is not the man who created the Tamil homeland, but the one who destroyed it. History belongs to the victors, but memory belongs to those who remember what victory destroyed.

What followed was not peace but choreography: victory day parades, presidential decrees, the language of healing but none of its labor. The silence that emerged was not the hush of rest but a silence legislated, patrolled and praised, a quiet that hummed with the electric tension of unspoken threats, the faint scent of stale cigarette smoke from the watchtowers. Mourning became sedition; inquiry, a threat. The war, having ended, could no longer be mentioned. And in that erasure, a different violence took root.

Every nation writes its wars backward, into something righteous, into heroism. But Sri Lanka buried the writing itself.

From the beginning, the media — Sinhalese and Tamil, Indian and international — was complicit in prolonging the war through absence, partisanship and a hunger for the byline that advertised proximity. Indian journalists wrapped themselves in flags: national, regional, linguistic, posing as neutral while carrying bias in their back pockets. Others shadowed the military, hopscotching from front lines to hotel bars, harvesting headlines under escort. Editorials mirrored Delhi’s mood. Western correspondents arrived like weather fronts: sudden, loud and gone, departing with a quote, not context. What emerged was not a record of truth but a collection of myths, set adrift from the facts they claimed to represent.

As battle lines hardened, so too did the narratives. Like their Saigon forebears, most correspondents worked the war from the 5 o’clock press briefings by Indian envoys in Colombo, imperious in bearing, colonial in posture, and nicknamed “viceroys” by Sri Lankans and foreign press alike. Assigned to write the first draft of history, they moved like looters through the ruins of testimony, their fingerprints smudging every shard of truth they collected. Beneath it all lay a deeper betrayal, not only of accuracy or detachment, but of intimacy: the failure to stay. Conflict became a credential, a line in the bio, a story rehearsed over drinks, an anecdote polished until the war itself seemed a backdrop for performance.

From their hotel balconies, they surveyed the war like a landscape: visible, containable, almost picturesque. They saw everything except the humidity of fear, the weight of breath before a door is knocked at midnight. One wrote with the assurance of having found the war’s pulse, speaking of “columns of soldiers, bayonets like needles of light.” I remember only columns of smoke, needles of bone. His prose marches; mine limps behind it, uncertain of its direction, unwilling to keep pace.

There were a few who slipped through the checkpoints and went north, sleeping on church verandas, writing by the glow of a half-broken lamp. Their notebooks smelled of mildew and sea salt. They wrote not of geopolitics but of the hush that follows shellfire, the moment when even the crickets fall silent. Those rare pages remind me still what witness sounds like when it no longer seeks to report, only to remain.

If the journalists failed to capture the war’s intimacy, the generals refused to even acknowledge it. The most curiously detached accounts came from Indian generals themselves, those who arrived under the flag of intervention and departed with the language of command. “Assignment Jaffna” by Lt. Gen. S. C. Sardeshpande (1992), “IPKF in Sri Lanka” by Lt. Gen. Depinder Singh (1992), and “Intervention in Sri Lanka” by Maj. Gen. Harkirat Singh (2007) render the war in a clipped operational grammar: missions, maneuvers, misunderstandings, glimpses of turf battles between diplomats and commanders. In state-licensed Sinhalese history, certainty prevails. Maj. Gen. Kamal Gunaratne’s “The Road to Nandikadal” (2016) narrates a precision campaign, a clean war in which there are heroes and villains and history ends at the lagoon. His map is tight, his memory exact; the Tamil dead register not as grief but as collateral. The account is too proud of its coherence, too indifferent to what had to be erased to achieve it. This is the architecture of all state-sanctioned memory: It is founded on erasure. Even in postwar Sinhalese journalism, distance lingers. The war appears as tragedy, yes, but as shared abstraction, not culpability; sadness without stain.

One exception is “A Long Watch” (2016) by Commodore Ajith Boyagoda, a naval officer captured and held for eight years by the LTTE. His memoir does not thunder with vindication. He writes not from command but from captivity. His reflections dwell in stillness: on friendship, patience, the blurred line between enemy and fellow prisoner. He does not defend; he does not deny. In this, his watch becomes a form of witnessing: unresolved, strangely generous.

Yet there came others who chronicled: those who watched from safer distances yet felt the moral weight of what they recorded. Frances Harrison’s “Still Counting the Dead” (2012) gathers testimonies of Tamil survivors — doctors, students, mothers — whose voices arrive like aftershocks. Timelines blur. Symmetry breaks. There is only pain. In “The Seasons of Trouble” (2014), Rohini Mohan follows those trying, often vainly, to live again, tracking surveillance, fear and disappearances rewritten as data. Her journalism does not trust normalcy. It listens to the background hum of dread.

Nirupama Subramanian’s “Sri Lanka: Voices From a War Zone” (2005), Gordon Weiss’ “The Cage” (2012), and Samanth Subramanian’s “This Divided Island” (2015) stand as careful, necessary works, bearing witness to the conflict’s devastating erasures and the nation’s struggle with memory. Nirupama offers a mosaic of lives across communities. Weiss delivers a concentrated account of the war’s harrowing final phase. Samanth travels a postwar landscape to capture the scattered voices left behind. Yet their witnessing, however meticulous, remains bounded by departure. They could leave; those they wrote about could not.

And yet, where words falter or are forbidden, another kind of witness emerges, one that speaks not in syntax, but in light and shadow.

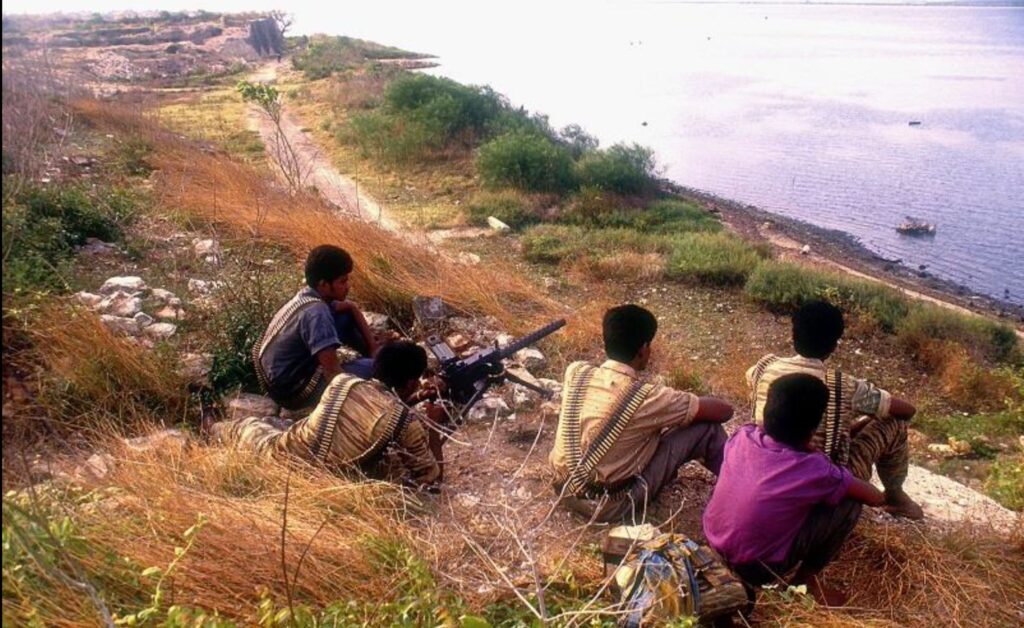

A photograph promises witness, but in war, witness is never clean. The camera arrives too late to prevent, too early to grieve, and always just in time to claim. In Sri Lanka, the lens was many things: evidence, weapon, trophy, threat. Some images became icons, others vanished; most were never seen. The Tigers knew how to stage. Cadres with rifles against jungle backdrops, smiling girls with cyanide capsules, funeral salutes frozen in militant grace — these were not records but declarations. They instructed memory. The state curated its own theater: aerial shots of bombed bunkers, white flags ignored, bodies blurred just enough to escape the charge of atrocity.

There were images taken from behind rebel lines: cadres barefoot in the undergrowth, rifles held without tremor, eyes trained just past the frame. Boys and girls, still children, faces set in expressions they had not yet grown into. The jungle was a backdrop, deliberate but not false. The cyanide capsules gleamed like pendants. One frame caught a woman crouched beside a small bundle, cloth-wrapped, impossibly small. Her face was turned away. Behind her, streaks of blood ran across the floor, a trail of what had been dragged and could not be named.

Another has a dog pulling at the body of a man whose face no longer held shape, viscera spilling from a ruptured belly. It revealed everything but explained nothing; too sharp, too clear. Perhaps that is what made it unshowable. Its clarity left nothing to interpret. Still another came from above: In the shrinking geometry of the No Fire Zone, aerial shots mapped tents and shelters like debris folded into the coastline. Bunkers erupted like fossils. Each frame insisted, withholding as much as it revealed. What it captured was not so much truth as trust, granted briefly and strategically, and always with a predetermined narrative.

I, too, raised a camera — sometimes out of instinct. The urge came when I realized the world believed nothing — nothing that didn’t fit inside a frame. Yet there were moments when I lowered the lens, ashamed not of what I might capture, but of what it meant to capture at all. The problem with war photography is not that it fails to tell the truth; it tells too many truths at once. Each image carries the gaze of the photographer, the pain of the subject, the distance of the viewer, the appetite of the archive. The image asks to be seen — and punishes the seeing. What is remembered is not the moment, but the framing: the boy running, the mother screaming, the fire caught midflame; iconic, consumable, unbearable in the abstract. But never in full. You never hear the silence after the click.

The image outlives the witness and the wound, until what remains is no longer pain but choreography, endlessly rehearsed in the archive. The same photograph is reused in report, rally, denial: cropped, captioned, stripped of doubt. Some images never leave the darkroom, not because they are flawed but because we are. To print them would be to admit what we saw, and what we did not stop. For the light they hold is not merely illumination, but exposure — of the moment, yes, but also of the one who chose to keep it. And that, perhaps, is the cruelest thing an image can do: make the unthinkable tolerable by making it still.

There is no innocent frame. Even the most honest photograph has edges; it excludes, arranges, decides what light will touch and what it will leave in shadow. And sometimes, in war, the shadow is where the truth resides. In the years since, the archive has multiplied: official, informal, algorithmic. Diasporas trade montages of martyrdom; governments release victory slideshows, social media feeds recycle suffering into pixelated loops: crying children, charred vehicles, armed men in slow motion. The photograph becomes both evidence and echo, repeated until it loses its urgency, kept until it loses its name.

And what of those who took the pictures and never shared them — who buried the roll, deleted the card, pressed the shutter and then folded the image into silence? Their restraint is not forgetfulness but another kind of testimony: one that refuses clarity, that understands the difference between revealing and releasing. Not every photograph must be shown. Some must remain in the dark, not because they are hidden, but because they are still grieving.

While some observed from afar, others could not look away and wrote from within the fracture itself. Tamil authors such as Rajani Thiranagama, Rajan Hoole and Daya Somasundaram write with unflinching intimacy. Their works, “The Broken Palmyrah” (1990) and “The Arrogance of Power” (2001), refuse resolution. Memory, they warn, does not fade when suppressed; it festers. Thiranagama, co-author of “Palmyrah,” was gunned down by the Tigers — not for betrayal but for refusing their script. The same unease pulses in N. Malathy’s “A Fleeting Moment in My Country” (2012), a quiet, searing account from within LTTE-administered zones. It is not a memoir of loyalty but of ambivalence. She lingers in the bureaucratic horror; briefings, burials, disappearances folded into the day’s routine. Her war is not exceptional; it is procedural.

Sharika Thiranagama’s “In My Mother’s House” (2013) listens not for heroism but for rupture, for violence across families, generations and villages. She writes as an anthropologist and daughter of the war. The LTTE, once a symbol of resistance, becomes in her telling a machinery of silence, a sculptor of fear. Her work is not about battles but about households emptied of sons, neighborhoods where memory itself becomes a risk. Her question is not how one survives war, but how one survives the future it destroys.

Some voices spoke not after but during. Adele Balasingham’s “The Will to Freedom” (2001), “Women Fighters of the Liberation Tigers” (1993) and “Liberation Tigers and Tamil Eelam Freedom Struggle” (1983) were written from within the machine they glorified. In her pages, the LTTE is not merely justified; it is generative. Women fighters become symbols; deaths are folded into doctrine. What haunts is not what she writes but what she withholds: doubt, regret, fracture. “Malaravan’s War Journey: Diary of a Tamil Tiger” (2013) is different. A young cadre, barely out of adolescence, he writes in a minor key, observing the weight of a gun, the ache of a wound, a glimpse of forest between ambushes. He died before the book could be published. His voice remains unpolished, unclaimed, unretouched, not a testimony of conviction but of consequence: how a boy becomes a fighter not from zeal but from absence of choice.

So nonfiction, for all its documents, falters. Tamil voices remain cautious, broken, because speech still courts danger. Sinhalese voices remain outward, tidy, because speaking plainly might rupture peace. Between them stands the global journalist, translating wreckage into story. Nonfiction offers a frame, a chronology, but this war does not move in time; it lingers like grief.

When the record falters, imagination takes over, seeking the truths that exist not in events, but in their lingering stains on the objects and gestures of ordinary life. Fiction understands what nonfiction cannot: that war marks the furniture, dulls the language, alters the way a mother cups her son’s face, as if bracing for his absence. It sees that grief is not something to describe, but something to survive. Fiction does not explain. It asks how war hollows the ordinary: sleep, love, memory, language.

Michael Ondaatje’s “Anil’s Ghost” (2001) remains foundational. It does not dwell on the machinery of war but on what the war erases: bones without names, truths that resist closure. A forensic anthropologist gathers evidence, but the more she exhumes, the less she understands. The novel sinks into the fog of aftermath, where knowledge unravels and certainty disintegrates under heat and time. Facts accumulate, yet understanding recedes, as if knowledge itself were being buried anew.

That lesson returns in Chemmani, where the soil again releases its dead. The graves are not literature; they are fact. Yet they read like fiction because they resist closure, echoing precisely what Ondaatje foresaw: that evidence may mount while meaning dissolves.

Shehan Karunatilaka’s “The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida” (2022) emerges from this landscape of unresolved truths as a dazzling, disquieting reply. It proposes a fantastical answer to the question of what happens to those who vanish, or to facts that refuse record. Its protagonist, Maali Almeida, a spectral war photographer navigating an otherworldly bureaucracy, has only a few “moons,” a Buddhist-inspired purgatorial time, to ensure his hidden photographs are revealed. The novel’s progression — fragmented, nonlinear, laced with acerbic humor — mirrors grief itself: recursive, uneven, disloyal to order. Through Maali’s journey, Karunatilaka shows how truth, once buried, finds unconventional routes to the surface. The surreal afterlife he imagines, populated by victims of violence, becomes a searing indictment of corruption, division and the complicity of silence. Some truths in Sri Lanka cannot be told conventionally. They require the audacity of fiction, even the supernatural, to inhabit the horror and demand acknowledgement.

Shobasakthi’s “Gorilla” (2001) and “Traitor” (2003) speak in the broken voice of one who once believed. A former child soldier turned novelist, he spares no one; not the Tigers, not the diaspora, not himself. His fiction is rough, obscene, wounded, yet thrumming with reality. “Gorilla” is brutal: war enters the protagonist’s life not as cause but as hunger, beatings, uniforms. Shobasakthi’s war does not elevate the Tamil struggle; it exposes its inner rot. Memory here is not inheritance; it is scar tissue.

In “Brotherless Night” (2024), V.V. Ganeshananthan brings the fracture inward. Her narrator, a young Tamil woman drawn into the Tigers’ orbit, recounts not a war of glory but one of collapse. The novel unfolds like memory: halting, circling, burdened by grief and impossible choices. Ganeshananthan does not paint the LTTE as villain or victim; she refuses clarity. To remember one’s people is not to absolve them. This is a distinction fiction is uniquely equipped to make.

Language itself bears the scars. Sinhala imposed by decree. Tamil encrypted to survive. English, hovering between, is neither refuge nor weapon, but a mask that lets many speak without being heard. Tamil fiction clings to the body: the missing brother, the slippers by the door. Sinhalese fiction, when it appears, often mourns the nation. One reaches for myth; the other endures through memory. One seeks meaning, the other survives what meaning cannot hold.

Nayomi Munaweera’s “Island of a Thousand Mirrors” (2016) braids myth and memory — a Sinhalese girl, a Tamil militant — refusing single allegiance, staining both sides with pain. Violence lands not as abstraction but as bruises on schoolgirls, as blood on kitchen tiles. Munaweera offers no reconciliation, only damage: shared, inherited, unfinished. In her pages, even belonging is barbed.

In “The Story of a Brief Marriage” (2016), Anuk Arudpragasam collapses time into sensation. His war has no battles, only breath; the feel of washing another’s body, the texture of touch amid annihilation. In “A Passage North,” the war has ended, but grief metastasizes. His narrator wanders not through ruins but through numbness. Stillness becomes a kind of reckoning. Arudpragasam does not write with outrage; he writes with silence.

Even the diaspora murmurs. Characters in Minoli Salgado’s “Twelve Cries From Home” (2022) carry the war in syntax, in absence, in silence. Her fiction does not document; it mourns. It does not clarify but clouds; it does not resolve but reverberates, like names the tongue begins yet cannot finish. Its narrators contradict themselves, not in error but as method. They falter, stammer, leave the sentence open; not for lack of language but because closure would betray the war’s unfinished breath. And in doing so, they come closest to its lingering truth: not what happened, but what remains in the marrow of those who survived it.

Fiction, having spoken where fact could not, now drifts into the dust of remembrance. What remains is not story but residue. And then, there is July: not a date, but a negative held too long to the light, overexposed, unfinished, recurring at the edges of thought. A scar across the map, a terrain of recurrence, a wound that loops rather than heals.

July 1983: Black July, when the veil first tore. July 1987: Martyrs’ Day, commemorating the Tamil militant known as Miller, the first suicide bomber, and the day of the signing of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord, an agreement that promised peace and delivered occupation. July 2001: the attack on Bandaranaike Airport, fire lighting the runways.

A litany of violence, anniversaries without peace, a tremor beneath the ground. Each July means something different, depending on the ash, the anthem, the absence, on which barricade you stood behind, or which door was kicked open in the night. For some, it is the month of martyrdom. For others, betrayal. Commemoration becomes geography. The ground itself changes meaning, and mourning becomes a minefield. To walk through it is to risk detonation.

To read Sri Lanka’s war is to read across shards: to read diagonally, across genres, across denials. We must listen diagonally, too: the general’s precision beside the deserter’s doubt, the satire of Karunatilaka beside the forensic ache of Ondaatje, the fury of Shobasakthi beside the steady anthropology of Thiranagama, the stillness of Harrison beside the fracture of Hoole. Even now, the war continues: pixelated, portable, repackaged. Even captions carry allegiance. In diaspora blog wars, WhatsApp forwards, YouTube montages where subtitles do the work of revision, TikTok tributes cut to mournful music and militant pride, memory circulates in pixels, its half-truths traveling at the speed of light: distortions untethered from fact, but no less capable of injury.

Future texts may come from daughters of the disappeared, from sons of soldiers grown old in silence, from poets who no longer translate their sorrow into English. They may come from the hands of archivists collecting rain-stained documents, half-burnt letters, schoolbooks with blood at the corners; the silence behind bulldozers. Among the stories withheld are those we withhold from ourselves. Some stories will arrive as photographs, uncaptioned, misfiled, stained with someone else’s fingerprints.

Perhaps this is the final honesty the war demands: to admit that narration will never be whole, that justice may never be named in time, that literature, too, has limits. It cannot bring back the dead. It only teaches us how to sit in their absence, quietly, like one sits in a room where grief has just left, but the dust has not yet settled. And memory, refusing to close its eyes, continues to look back. It does not ask to be named, only to remain, like the faint outline of a photograph never brought to light.

And somewhere in Chemmani, the dust does not settle; it shifts, bone by bone, as if the earth itself were breathing, holding within its breath the hush that the undeveloped photograph still holds in light, like water remembering the weight of the bodies it once carried.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.