Leaked videos show in chilling and unprecedented detail Syrian military personnel committing a massacre in 2013 of 288 civilians, including seven women and 12 children. In the videos, which were leaked to the authors in 2019 and amount to 27 takes of the massacre in its different stages, military personnel show their faces to the camera and appear at ease and in full control before they execute their civilian captives in cold blood. A subsequent two-year investigation based on open-source intelligence and numerous interviews, including with some of the executioners who continue to serve as officers in Syria’s elite military intelligence unit, has revealed that the massacre unfolded on April 16, 2013, in the Damascus district of Tadamon. The footage sheds light on the inner workings of a regime that relied upon systemic mass executions of civilians in addition to indiscriminate bombardment of civilian areas during the country’s 11-year war.

New Lines acquired details of this investigation and verified the authenticity of the footage and evidence presented by the authors.

So far, much of the attention in public debates has gone to the clashes during the war or to the regime’s merciless bombardments and airstrikes on opposition-held territories. But the neighborhoods under regime control, just on the other side of the front lines, have been comparatively neglected. The Tadamon massacre videos, our interviews with perpetrators and survivor testimony demonstrate that there was a full-blown, murderous cleansing operation unfolding. As we deepened our research, we realized that this massacre was a snapshot in a much wider policy of destruction and extermination that the regime enacted in the southern suburbs. The extent of this genocidal microcosm in this area went far beyond this one videotaped massacre and includes at least four forms of violence: systematic mass killings, imprisonment, sexual violence and economic exploitation.

Of particular focus in the investigation are the two main executioners shown in the footage. They are Amjad Youssef, 36, who at the time of the massacre held the military rank of warrant officer, and the now-slain Najib al-Halabi, born in 1984, who held no official rank as he was serving in the armed militia known as the National Defense Forces (NDF). In three separate videos that each last about seven minutes, these two men show themselves in broad daylight while executing 41 civilians. Then they dump the bodies in a pre-dug pit prepared with car tires for incineration.

In the footage, Youssef is seen dressed in green military fatigues and an olive-colored fisherman’s hat. He is focused, stoic and precise, and he works efficiently toward completing the task within a matter of 25 minutes. His brother-in-arms Najib is wearing gray military fatigues and is at ease, smiling, smoking and even talking straight into the lens. The shootings appear to be routine and repetitive: One perpetrator takes out a blindfolded and zip-tied civilian from a white van and marches him to the large, pre-dug pit. Another executes him with an AK-47 assault rifle. A few victims are shot with pistols. The killers carry out the executions in standard procedural fashion, speaking little except for barking orders at the victims (“get up,” “get out,” “walk,” “run”). One agent is filming, while the other two are shooting. They are not particularly emotional but are clearly enjoying the job. At some point, Najib turns the camera around, smiles into it and sends a dutiful message to his “boss”: “Greetings to you, boss (معلم), for your beautiful eyes and your olive uniform when you wear it.” According to our research, the reference to “beautiful eyes” was either to Jamal Ismail or Abu Muntajab, both of them commanders of the executioners.

The perpetrators clearly prepared the execution site to have ideal conditions without any interruptions and ultimately not only to execute the victims but also to burn them and leave no trace. They are comfortable and familiar with the site of the massacre, killing in broad daylight, suggesting that the area is firmly under their control. They seem neither in a hurry to finish the job nor worried about any threats. They deceive some of the victims by suggesting that they are being transferred to another area and that this part of the road is exposed to snipers.

“Sniper, you bastard!” yells Youssef as he makes a victim stagger into the mass grave, then shoots him. With one victim, he is impatient, blaming him for not dying from the first and second shot. At the third shot, he snaps at him: “Die, you bastard! Haven’t you had enough?” The end of the video suggests that the massacre is finished, as one perpetrator asks: “Are there any others?” Finally, there is silence and only faint moaning emerges from the mass of bodies underneath the perpetrators’ boots.

The videos, already shocking for their atrociousness, stand out in their brevity and callousness among the thousands of hours of footage that we have examined throughout our respective careers as researchers of mass violence and genocide in Syria and elsewhere. Particularly shocking about the Tadamon videos is the fact that the intelligence officers who committed the massacre were on duty and in uniform; they report to President Bashar al-Assad himself, and yet they chose to show their faces in the incriminating footage. At several points during the video, they looked straight into the camera seemingly relaxed and smiling. In documenting their own actions, they used HD video quality.

In one video Youssef is seen driving a bulldozer that he later uses to dig the mass grave, which is about 10 feet deep. The street on which this occurs appears bombed out, and the whole scene looks like the aftermath of mass destruction from shelling, bombing and clashes. There are bullet holes in the walls. You can see through a building. There are no sounds of war: no shelling, no shooting, no clashes. Just quiet, pierced by the shots of the executions and occasional smoke from the killers’ guns. The camera operator takes his time in shooting the footage: He mostly focuses on the mass grave. The victims are then brought into the frame and shot one by one. The grave fills up quickly and becomes an entangled mess of bodies, clothing, blood and car tires.

The victims’ eyes are bound over with transparent duct tape or cellophane plastic wrap. Their hands are tied with white plastic zip ties, normally used for tying cables together. (These same zip ties are used by the police around the world as plastic handcuffs.) Most of the victims are wearing modern, casual clothing: jeans and shirts, track suits or dishdashas (white robes worn by men). A few are wearing indoor pajamas, suggesting they were lifted from home or from security checkpoints. Some victims look outright poor, others look well groomed; none look like they have been severely tortured or like the emaciated detainees the regime keeps in its gulag-like labor camps. They are meek and do not resist or protest, and they follow the perpetrators’ orders: They get out, they walk, they stand up. All are shot, with the exception of one older man, who is beheaded by Youssef.

Most victims die in silence. A few beg, weep and yelp; others try to bargain, adjure or beseech. None of the victims utters the “Shahadah,” the Muslim testimony of faith, before death. Some are kicked or pushed into the pit, then shot; some are shot and only then kicked in; others are shot while falling. One of the victims pleads: “Please, for the sake of Imam Ali,” but Youssef is inexorable and hurls him in: “Fuck you, son of a bitch.” A few mishaps occur during the executions: An older man clumsily walks into the wall instead of the pit, then tumbles in it with one leg and calls out in pain for his father. In another case, the executioner misses a young male victim, who falls down, freeing his hands. He rubs his eyes but is then shot in the head. Some bodies seem to be moving in the pit, but Youssef peers, aims his Kalashnikov with one hand and dispatches them with a mercy shot.

The only seven female victims, wearing hijabs and overcoats that characterize conservative Muslim women’s clothing, are killed with a ferocity and hatred the otherwise passionless killers do not express to the men. Out of frame, one of the sobbing women is barked at: “Get up, you whore!” (!طلعي شرموطة). Her pleas fall on deaf ears, as she is dragged up by her hair and dumped into the hole. Two women shriek uncontrollably when Youssef kicks them into the grave and executes them; the others face their fate in silence. In another video, the camera pans over a group of dead children, including infants who had been stabbed or shot, lying in a dark room as the camera operator tersely speaks: “The children of the biggest financiers from Ruknaddin neighborhood. Sacrifice for the soul of the martyr Naim Youssef.”

Although the vast majority of the victims were Sunni (including ethnic Turkmen), a few may have been Ismaili, probably targeted for political activities or disobedience, our investigation shows. Judging from the perpetrators’ perception and attitude, middle-aged Sunni men were by definition suspect, unless they affirmed their loyalty and obedience to Assad. Otherwise, they were seen and treated as sympathizers, hidden agents or potential supporters of the opposition. The ethnic Turkmen residents’ celebration and welcoming of the Free Syrian Army’s invasion of the neighborhood supposedly was evidence of this. But this was an overblown fantasy since all victims we identified were from apolitical, working- and middle-class families. They were arrested in Tadamon or at the checkpoints surrounding it, transported to the massacre site and executed. They probably never imagined this level of violence could befall them on what would have been an ordinary day in their lives, going about their business inside a regime-controlled area during the early years of Syria’s war. And as the atrocity was committed, they probably never understood why this was happening to them.

The Tadamon neighborhood is located in the southern entrance of old Damascus. The Arabic “tadamon” translates to “solidarity” — originally with those who were displaced by Israel during its invasion of the Golan Heights in 1967. Displaced Golanis began living on the farmland in southern Damascus and built informal dwellings, utilizing private funds without access to state subsidies. The burgeoning community was then officially recognized, retroactively, as part of the Midan neighborhood and was christened Tadamon.

In the 1990s, waves of domestic labor migrants flocked there from the country’s periphery. The 2003 drought that deeply affected the country’s agricultural sector forced many farmers to abandon their lands in a desperate act to find a means of survival in Damascus. Villagers followed their paesanos, and Tadamon came to absorb this internal chain migration until it became a sizable informal district with the highest population density in Damascus.

The majority of the population was Sunni Arab, but Alawites, Druzes, Ismailis, Turkmens and Kurds also called it home. The divergence among these communities was based on the overlap between their sectarian and regional affiliations. For example, Alawites on Nisreen Street were identified with their village of origin Ein Feet, while the Druzes from al-Jalaa Street had fled from Mount Hermon. To understand the dynamic of mass violence in Tadamon, it is important to look at these socio-spatial divisions that were shaped by competing communities.

The Syrian mainstream media referred to Tadamon as “Little Syria,” based on the Assad regime’s supposedly secular façade and rhetoric of coexistence in the country. But Tadamon was a paradoxical space: Yes, Syrians from diverse sectarian, ethnic, political and regional backgrounds lived together in intimacy, yet it was a tense environment that became increasingly polarized. Tadamon is one of the few places where victims and their perpetrators were direct neighbors.

How did these complexities shape the conflict? The social cleavages in the neighborhood may have caused distrust among different groups, but there are countless neighborhoods across the world where this is the case. There is nothing special about uneasy coexistence. But it was only under a creeping process of polarization in 2011 that the Syrian regime was able to foment antagonism and escalate tensions among the historically established communities. This increasingly extreme polarization between neighbors reflected on the patterns of mobilization.

When demonstrations began to appear in various Damascus neighborhoods in the spring of 2011, Tadamon witnessed peaceful public protests that were short, sporadic and sometimes chaotic. The protest movement effectively split along local-oriented groups’ interests, and at some point, there were three different Local Coordination Committees. Similar divisions could be seen among pro-Assad communities, which split into competing militias. In the end, the area was divided into at least 13 separate (para)military terrains controlled by various warlords. From the summer of 2011 onward, Tadamon, too, experienced the familiar cycle of opposition protests: regime repression, opposition militarization, regime escalation.

The regime’s response to the demonstrations in 2011 was to establish the “Shabbiha,” a loyalist militia that violently repressed the mass protests. Dressed in civilian gear and drawn disproportionately from young men of minority backgrounds, the Shabbiha stormed neighborhoods, dispersed demonstrations and committed property crimes, torture, kidnapping, assassinations and massacres. Whereas the Shabbiha seem to have appeared out of the blue, it was the regime that had condoned, incited, steered, and gradually organized and reorganized them through its elaborate patronage system. It was clear that the regime set these militias up to do dirty work with plausible deniability. In 2011, the Shabbiha were formalized into the NDF and given impunity to set up checkpoints as well as arrest and detain people, and during demonstrations they had license to kill. One of the perpetrators in Tadamon was a top Shabbiha.

Whereas the Assad regime was highly experienced and competent in repression against civilians, it was less adept at warfare, and this was demonstrated well in 2012. The regime steadily lost territory across Syria, and by early 2013, half the country was under the control of various rebel groups. In the broader Damascus area too, the front line had approached the city as most of Eastern Ghouta and the southern suburbs were in rebel hands. In February, rebel forces launched a large-scale coordinated attack on Kafr Souseh from the south and Jobar from the east. Had the offensive succeeded, the rebels would have been within whistling distance of the regime’s major intelligence branches in Kafr Souseh. The offensive failed, but the specter of potential defeat loomed large, and more important, the front line had now reached Tadamon.

How did New Lines come to possess information about the Tadamon massacre?

In June 2019, Üngör was attending an academic conference in Paris on the scholarly uses of video testimonies of survivors and eyewitnesses of mass violence. He had prepared a presentation on how to analyze video footage of and by perpetrators. As he was waiting for his panel, a Syrian friend living in Paris called and wanted to meet urgently. They met immediately, then sat down in the back of a quiet café as the friend pulled out his smartphone and urged Üngör to watch a video of it. What we saw in this and subsequent videos shocked even us seasoned researchers of mass violence and atrocities: The Syrian Military Intelligence and the NDF conducted a systematic extermination of civilians in Tadamon neighborhood in 2013 and beyond.

We started with the main execution video itself. And there was one good clue to the precise time of the massacre, as one of the video files had a timestamp of 16-4-2013. Locating the precise site of the killings was more difficult: The mass grave was dug in a fairly narrow street, and the architecture and urban design suggested that it was somewhere in the suburbs of Damascus, but whether it was in Eastern Ghouta or in the southern districts was unclear. We saw little more than that the building directly across from the execution pit had a blue balcony and a red roof, and one wall had palm tree artwork. Otherwise the entire area was bombed out and nothing was recognizable: No shop, sign or landmark was visible. But after watching the video over and over again, we noticed graffiti on one of the walls behind the perpetrator: “Conquest of the town of Yalda, 14/3/2012.” This text, spray-painted most likely by rebel factions, suggested that the location might have been the southern town of Yalda, which fell to rebels briefly in 2012. (In hindsight, we were wrong and a friend pointed out to us that the red graffiti turned out to say “Stamp of the municipality” and the location was in the neighboring working-class district of Tadamon, but the clue was a start, because Yalda is just south of Tadamon.) The graffiti prompted us to reach out to opposition activists and rebel factions who had been active there.

Since we could not travel to Syria, we asked for help from a research assistant who possessed both expertise and networks in the victims’ communities. He discreetly scouted and videotaped the area, searched for victims and arranged confidential interviews with survivors. These interviews were carried out via relatively secure software, and interviewees’ names and identifying information were shared separately and erased from the records. We followed strict cybersecurity measures. We also conducted digital interviews with eyewitnesses, bystanders, human rights defenders and former Free Syrian Army fighters. We also fulfilled our fiduciary duty as Holland-based academic researchers and informed the Dutch police that we had these videos in our possession.

During our research we found numerous people who identified the location of the street on which the massacre unfolded as Daboul Street in Tadamon, based on snapshots of the videos we showed them. The accounts converged to pinpointing the place near the Othman Mosque on al-Biradi Lane, an area that was under the regime’s control during the entire conflict. The neighborhood was divided into two parts by a fairly stable front line that on April 16, 2013, passed through Othman Mosque to al-Najoum Cinema. Here, we met our limits in identifying the precise street, so we asked for technical assistance from geolocation and open-source analysts. The experts provided conclusive evidence, based on the nine pillars of the building next to the pit, that confirmed our assumption that the massacres indeed took place near the Othman Mosque in Tadamon.

But who were these perpetrators? Why did the two main killers wear two different uniforms? It suggested two different agencies at work, but they did not carry any insignia or patches on their shoulders. Their accents only occasionally suggested a regional dialect as they mostly spoke “neutral” Syrian Arabic that could pass for Damascene or the accent of the average government worker in and around Damascus regardless of origin, and nothing they said provided any clue on their personal or professional identities, as nobody addressed another person. The task ahead was daunting: We had to find the responsible agencies for the neighborhood and try to locate them online, either in the pro-regime media or in opaque online Facebook groups of the intelligence agencies.

Since 2011, Facebook has been a popular platform among pro-regime Syrians, including perpetrators, who often post their stories and photos of their deceased comrades. The key question was: How can we elicit information from them without risking anyone’s security? We got lucky: In 2018, we had already created a Facebook profile of a young, pro-regime woman from an Alawite middle-class family from Homs, “Anna.” The purpose of this assumed identity was to closely observe Syrian perpetrators in their online environment and approach them directly to interview them. We carefully crafted Anna’s personality and Facebook posts to fit into the perpetrators’ ecosystem: They would not doubt the motives of an Alawite middle-class girl from Homs who was studying abroad and researching the conflict. The profile was a roaring success: We managed to interview dozens of Assad’s perpetrators, including some relatively high-ranking ones.

When we happened upon the Tadamon massacre video, Anna was already well embedded in pro-regime circles: Her friend list included soldiers, militiamen, officers, business owners, journalists and indeed intelligence agents. Considering the routine professionalism of these killings, the prominence of the intelligence agencies within the framework of the Assad regime, and the sensitivity and discretion that such a mass killing operation would require, it was likely that at least one of the shooters was from an intelligence branch. Since we took a close look at the faces of the killers (more than was healthy for us), we started browsing the Facebook pages of the army, intelligence and militias that were active in the neighborhood of Yalda and southern Damascus more broadly. Maybe we would bump into a familiar face. But it was like looking for a needle in a haystack: We had no name, no branch number and very few other leads. Our interviewees recognized the main shooter but referred to him by the generic Mukhabarat (intelligence services) operational nickname “Abu Ali” and did not recall his full name or any other details. For months, we sought in vain, and our patience increasingly turned into desperation.

Then one day, we recognized the main shooter in a photo of the Military Intelligence’s District Branch, also known as Branch 227.

The main executioner, Youssef, is clearly recognizable by a horizontal scar on his left eyebrow. In the massacre video, he had looked directly into the camera, and the image was crystal clear. Before we sent him a friend request, we browsed through his posts, many of which were public. It was definitely him. His physical appearance has transformed a bit: The shooter’s slender and skinny body dressed in military fatigues had become more muscular. His Facebook profile was that of an ordinary and typical Syrian perpetrator: portraits of father and son Assad, snapshots of his friends, picturesque images of his village, selfies of working out at the gym, and most important, a melancholic post in which he mourned his friend and colleague, Halabi, clearly the second shooter. We were elated: We found both of “our perps.”

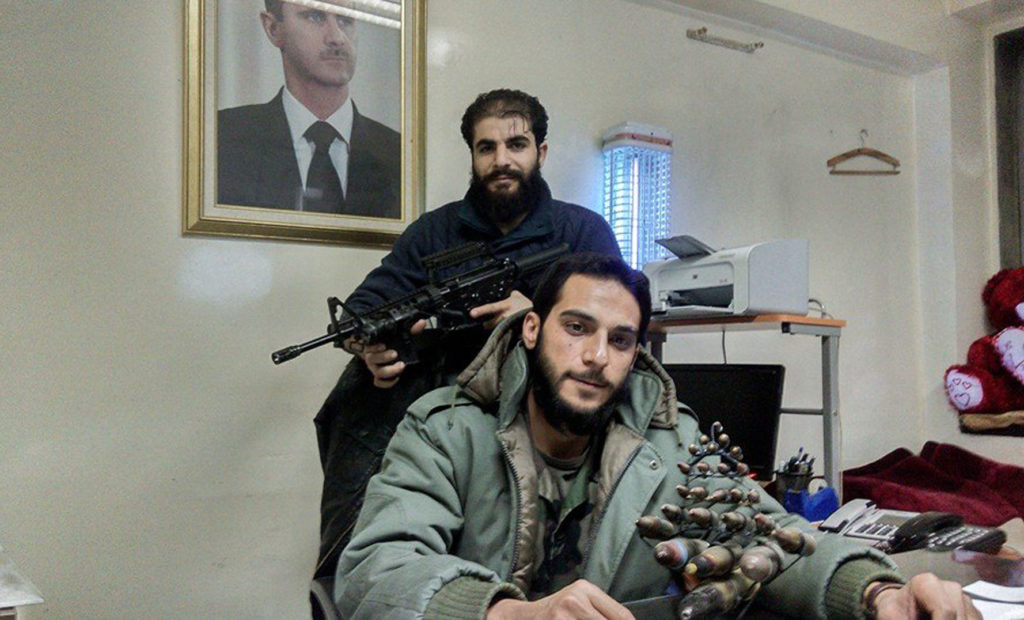

He accepted Anna’s Facebook friend request and was cautious but also clearly curious how and why Anna reached out to him. When we explained to him in vague terms through Anna’s persona that we were conducting academic research on the course of the conflict and that he seemed to be in “the army,” he agreed to talk to us. Throughout a period of six months, we chatted and spoke to Youssef several times, and we conducted two long video interviews with him. During the first interview, he was at the branch, sitting in a tracksuit and a black jacket at a desk with a portrait of Assad behind him on the wall. This was the first conversation to get to know each other, and we explicitly did not use the term “muqabala” (interview) but the word “ta‘aruf” (introduction). He was a bit tense, and after the usual exchange of pleasantries, questioned Anna more than Anna was able to question him. But his behavior in itself was also an object of our research. After all, Anna had on her screen an actual perpetrator sitting at his desk. He had a computer in his office and called for coffee whenever he wanted some. In the end, he seemed convinced and agreed to a second conversation.

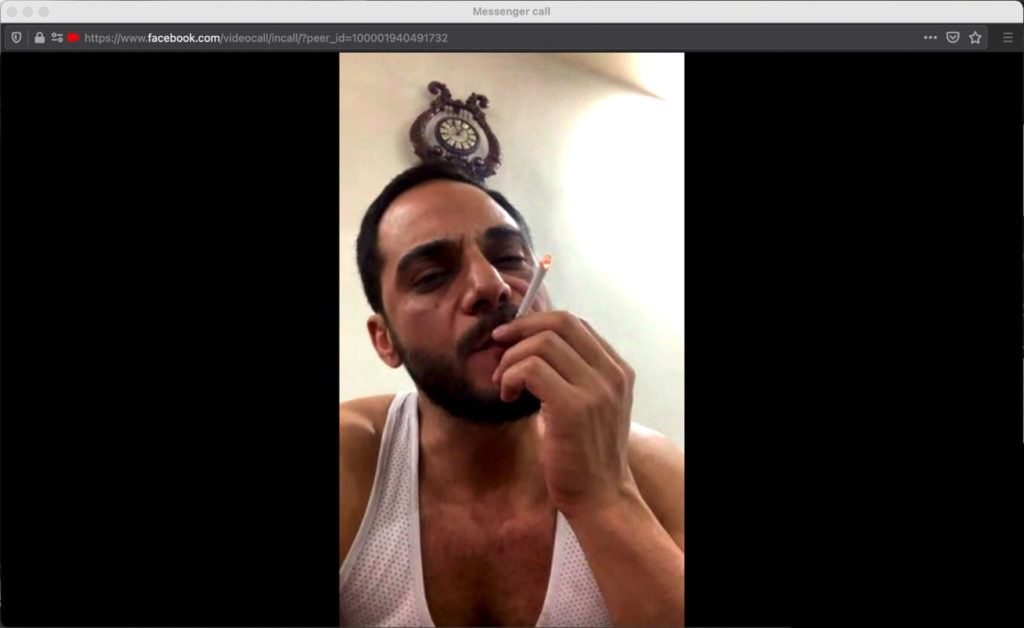

This second interview was much more informative and interesting. We spoke late at night, when Youssef was in his home on his sofa wearing a sleeveless white undershirt while chain-smoking, drinking and snacking on a cucumber. He told us that he was born in 1986 in the Alawite village of Nebaa Tayyib in the Ghab district in central-western Syria, about 40 miles northwest of Hama. The eldest son of a blended family of 10 siblings, they were all raised strictly to honor the family’s religious heritage of their great-grandfather, a prominent Alawite sheikh. Together with his siblings, Youssef often practiced the religious rituals at the holy Alawite shrine, Bani Hashim, just outside the village.

Youssef told us that in 2004, he enrolled in the Military Intelligence Academy at Maysalun in al-Dimass district in Damascus and underwent an intensive nine-month training. For the 18-year-old Youssef, working for the Military Intelligence was his best shot at living a different life from his ancestors, who had suffered the hardship of working on tobacco fields and struggled to earn a living. Youssef had dreamt of having a decent middle-class life: a house, a car, a family. Youssef also had a hidden desire to break free from his father, an aloof Alawite sheikh and a former military/intelligence agent. But working for the Mukhabarat only solidified his links to the pro-regime community, and he became a “son of the institution,” as he put it. Contrary to his ambition of independence, it was now “like father, like son,” he said with a tinge of resignation. In our interviews, even at his current age of 36, he still expressed a profound fear of his father, and according to one of his acquaintances, he never dared to smoke in his father’s presence.

Through the 2000s, Youssef did well in his career. He steadily climbed in rank and became a warrant officer interrogator with routine office hours at the branch. By 2011, he was working for the District Branch 227, a grim organization based in Kafr Souseh, and was responsible for the arrest, torture and killing of thousands of the regime’s political opponents. If his harsh training brutalized him, then his work as an interrogator at the branch must have further habituated him to committing acts of violence against fellow Syrians. The 2011 uprising must have further changed his life. He was dispatched to the operation department and assigned to command the military operation on the southern Damascus front lines. From 2011 until June 2021, he was the official responsible for security on the front line in the districts of Tadamon and Yarmouk. There is some propaganda footage of these operations, and Youssef is visible in one video clip, eyes heavily frowning, cigarette in his hand, while he converses with a group of fighters ready to storm Tadamon.

During our interviews, Youssef rebuked our use of the term Mukhabarat and instead admonished us to use the term “army” or “armed forces”:

There is nothing in the crisis called intelligence; it is all army. I am an intelligence officer. I worked as the army did. My job was that of the army. My job is not street fighting and incursions and bombs, etc. This was my job in the crisis. There was nothing in the crisis called intelligence. We were all army; our job was the same job.

His allergic reaction to the very word “Mukhabarat” spoke volumes: It did not denote denial of its existence but spoke to the secretive and taboo nature of the intelligence agencies in Syria. An open conversation about them was clearly not permissible, although he did discuss other taboo topics such as sectarianism. This might have been related to Youssef’s self-image. He most of all made it clear that he saw himself as “ibn al-muassasa” (a son of the institution). On the one hand, this meant that he was steeped in the tradition and culture of Military Intelligence and that his loyalty was first and foremost to that agency, above and beyond any sectarian or regional loyalty. On the other hand, he was quite literally a son of the institution in that his father had been a military officer who had served in the army for decades.

Another major taboo casting a shadow on the interviews was the massacre itself. At no time during the first few months of interviews and other communication with him did we intimate that we had seen the video or were aware of his crimes. As he explained his vision on the causes and courses of the conflict, it became clear that he had been particularly touched and radicalized by the death of his younger brother, who died serving in the army on Jan. 1, 2013. At this point in the interview, he became more emotional, started finicking with his cigarette lighter and mumbled: “I took revenge, I’m not lying to you, I took revenge, I killed. I killed a lot. I killed a lot, I don’t know how many I killed.”

After a few months, we confronted him with the massacre and let him know that we had seen the footage. First, he denied it was him in the video. Then, he said he was just arresting someone. Finally, he settled on the justification that it was his job and expressed his content: “I am proud of my deeds.”

Why did Youssef agree to talk to us for so long? It was probably a mix of curiosity, solitude and frustration. Since the war has ended, in a Pyrrhic victory and economic exhaustion, Assad’s perpetrators often live silently with their memories, drinking araq and chain-smoking cigarettes. He was also discontented with recent work arrangements since he had been removed from his position as operation commander in Tadamon and Yarmouk and relocated to boring office work in the branch. His confession to the mass killing in Tadamon was not entirely surprising: His wife and children probably knew nothing, and we were likely the only ones who had ever asked him about it. When we finally revealed to him that we had all the videos and had collected through our investigation a trove of incriminating information about him and his unit, he began to threaten us — or rather he began to threaten Anna’s persona: “Come to Damascus or you will lose everything you love,” he said angrily.

Since the 1970s, Hafez al-Assad has built his intelligence empire with four main services: General Intelligence or State Security, Political Security, Military Security and the Air Force Intelligence. Some services have subdivisions, some of which became eminently powerful in their own right and began to constitute a significant and relatively independent actor.

The Syrian intelligence services are distinguished from many of their counterparts around the world primarily by their broad powers to use force against Syrian citizens. They are allowed not only to wiretap and spy on people, threaten and manipulate them, but also to arrest and imprison them — often without warrants and rule of law protections. Their prisons are characterized by systematic, extensive and brutal torture conducted by professional torturers.

The Syrian Mukhabarat is as powerful as it is elusive: It is an immensely powerful actor in the conflict but unresearchable. It is borderline suicidal to walk into Damascus and start asking questions about Mukhabarat structures, workings or impact (unless the regime trusts the person). Intelligence staff operate under nicknames or the generic sobriquets “Abu Haidar,” “Abu Ali” or “Abu Jaafar,” and it is strictly prohibited to identify them. This deliberate practice by the Syrian intelligence services is to maintain secrecy and induce fear. It mystifies intelligence operatives and creates overblown myths about their personae and capabilities. But in this video, the perpetrators are blatantly visible.

The District Branch, known as Branch 227, is in charge of Damascus province and its countryside. From its beginning in the 1980s, it was headed by notorious spy bosses like Nizar al-Helou (1942-2016), Hisham Ikhtiyar (1941-2012), Rustom Ghazaleh (1953-2015) and Imad Issa. Shafiq Massa was the director in 2013. At the time of this writing, Kamal al-Hussein runs Branch 227. Its headquarters is a grim W-shaped building in a Mukhabarat complex situated between Damascus University and Umayyad Square, right across the street from the Ministry of Higher Education.

Youssef’s Facebook friend list was a gallery of killers. One of his Facebook contacts was Jamal al-Khatib, the highest-ranking Mukhabarat operative we ever interviewed. Originally from next-door Qadam neighborhood, the officer carefully masked a ruthless personality behind a loud, jolly father figure with a contagious smile and salt-and-pepper hair. This persona is strong enough to fool anyone. For example, in a Dec. 3, 2013, CNN report, he is introduced as “a military commander who goes by the name of Abu Aksam,” as he shows CNN reporter Frederik Pleitgen around Sbeineh, just south of Tadamon. He accepted our friend request, and in one of two interviews he confided in Anna: “I am telling you something I shouldn’t. I am the boss of Youssef.” He insisted on knowing who put her in touch with Youssef, calling him “a hero, brother of a martyr, definitely not a small head.” The conversation then took a sharp turn when Anna asked him about the alleged violations:

Anna: A while ago, you told me about reforming detainees in prisons, but the media says that the Syrian regime has killed people in its prisons. And committed massacres against them?

Jamal al-Khatib: My answer is very simple: Why take him to prison and kill him and then be accused of killing him? I rather kill him in the street, and it’s done, and he died in battle. If you were not in my crosshairs, and you are an enemy of me and you are ruining my country, why would I take you to prison and kill you in prison and then be accused of killing you? This question is asked a lot, but it is stupid. Someone I can kill in the street without anyone seeing me, why do I bring him to my prisons and give him a number, food, and drink, and he is a burden on the state? Do you know they eat what we eat? They eat what we eat. Why should I bring him to eat and drink from my food and drink and cost the state, so they accuse me of it, in a way more stupid than this? … When I arrest 10 or 15 armed men, they need 30 to 40 soldiers to accompany them. Why the trouble if I can kill them in the street and relax? Why should I kill them in prison? I rather kill them in their places and be done with it.

Now that we had the Mukhabarat circle sorted out, what about the other perpetrator, the one in gray military fatigues? Youssef’s wingman in the massacre video was Najib al-Halabi, a.k.a. Abu William, who we found tagged in a Facebook post on the “Martyrs of Tadamon” page. Druzes originally from the Golan, his family was displaced to Damascus and he himself was born and raised in Tadamon. Unlike other residents in Tadamon, he was privileged and ran a club before the conflict. In 2011, he created the first Shabbiha group in Tadamon and stationed it right by the Othman Mosque on the front line, which made him a hero in the eyes of the loyalists. He also seemed to have somehow gained a level of expertise in tunneling and digging pits and trenches, and he was often called upon by his colleagues to supervise and advise in these activities either on the front line or for massacres.

In the massacre videos, Najib stands on the edge of the mass grave, smoking a cigarette, smiling into the camera, and flashing the V sign for victory. He appears to show no distress while committing the massacre against civilians that he personally knew in some capacity as he grew up with them, according to our research. Also based on our research about his personality, Najib seems to have amassed a reputation for being humble and intelligent, a good listener and generally liked by people who knew him. Apparently, he never showed his hatred or dark side to anyone: “You wouldn’t know that he would do this. I was shocked when I saw the video,” said one person who knew him. But he had enemies: Najib was killed during tunneling activities on the front line in 2015. (Some believe it was an inside job, but that aspect is beyond the scope of this investigation.)

The Shabbiha was launched with the expressed intent to not be traced back to the regime’s official armed forces. This way, the regime could (and did) argue that their violence was the work of enraged vigilantes and that it did not control them. But in Damascus, the militias were run by a friend of the palace, Fadi Saqqar (real name: Fadi Ahmad), a chinless, chain-smoking, high school graduate whose deep, dark circles under his eyes betrayed a constant lack of sleep. Although he comes from a privileged family (his father was a former intelligence officer), he was jailed for corruption before the uprising. His father’s connections with the regime failed him, and it is said that he killed a fellow prisoner before he received a special presidential pardon because his services were needed for the 2011 repressions. He not only set up the Shabbiha but was also seen personally attacking demonstrators with a knife and quickly became a prominent regime broker who made a number of public appearances with Assad. Fadi Saqqar usurped power and enriched himself to the extent that even Assad loyalists despised him — Youssef, for example, expressed nothing but deep contempt for him.

Between the foot soldier Najib and the mastermind Fadi Saqqar stood the Shabbiha’s commanding officer for Tadamon, a 50-something male named Saleh al-Ras, better known under his moniker Abu Muntajab. A creepy, lanky man with a pencil mustache — several women we interviewed later would identify him as their rapist — Abu Muntajab ran a reign of terror in Tadamon and was characterized by his colleagues as “the Hitler of Syria.” When Najib recited a dedication to the “boss,” he might have been addressing his direct superior Abu Muntajab, but it is also possible he was addressing Maj. Gen. Bassam Marhaj al-Hassan, chief of staff of the NDF at the palace. A uniquely powerful person in Syria, “Uncle” appears to the uninitiated like any nondescript vegetable seller at the weekly market, yet he wielded so much power that he could override any decision by other commanders because of his very close ties with Assad. According to numerous witnesses we interviewed, he would call the radio channel code 001, which connected him to Assad, who once gave the order to “bomb the neighborhood by every means you have.” The Tadamon massacre videos and our research demonstrate conclusively the collusion and cooperation between the Mukhabarat and the Shabbiha.

The videos at hand are a snapshot of the regime’s silent, industrial killing process in the areas under its control. As the opposition militarized and conquered parts of Tadamon in November 2012, the regime undertook a whole process of segregation and subjugation. Security clearances were given only to those who were allowed to stay in the neighborhood by the Branch 227 of the Military Intelligence, through the NDF commander controlling the lane. This clearance was required for any type of activities, whether an emergency health care trip or a personal visit to a friend. Furthermore, Branch 227 issued special identification cards for the neighborhood residents. There were two types of identification cards: yellow for the residents in neighboring Daf al-Shouq and blue for the residents in Tadamon. These cards contain detailed information about the cardholder, including name, address, family members, place of birth, etc. By doing so, the branch established a massive surveillance system and collected meticulous information about the inhabitants.

The first victims of massacres in Tadamon were taken from their home or street on foot to locations not far from where they lived, and their corpses were left on site where everyone might know them. The videos of these incidents’ aftermath show that they were shot at close range. These victims of the regime’s mass executions were largely forgotten through the course of the conflict. Videos of these incidents’ aftermath were overlooked or manipulated in the war of narratives between the regime and the opposition. After November 2012, victims were taken to scheduled sites of extermination either on foot or by minibus. Then they were shot one after the other from behind, and their corpses were burned to ashes. This method of killing and burning emerged because the perpetrators struggled to conceal their deeds and get rid of the piles of bodies in the neighborhoods’ alleys. As a result, each single perpetrator created his own execution site. Youssef had his own, but another example was the NDF commander Ibrahim Hikmat, better known as Abu Ali Hikmat, a stocky military figure with distinctly dyed hair, who was a young member of the Defense Companies, the infamous killing squads of the 1980s. Abu Ali Hikmat built his own primitive crematorium to burn the bodies of victims picked up from his checkpoints and from al-Mujtahid hospital. His soldiers often bragged about his meticulous skills in killing people and destroying evidence, claiming that his group had killed at least 30,000 civilians from 2012 to 2015. This might be an overstatement of proud perpetrators, but it is an illustration of the extent and scale of the mass killing in Tadamon. As one resident described: “We were smelling the coppery scent of human flesh burning every day.”

Imprisonment is a second form of violence in Tadamon. By the end of 2012, Tadamon became a huge urban prison with over 60 security stations and checkpoints. Branch 227 and NDF checkpoints mushroomed and were stationed in the entrance of each ally of the neighborhood in one square kilometer between al-Jalaa Street and the front line. NDF commanders constructed walls, dividing the neighborhood into 15 zones, and each group documented and registered the residents in their territory. These private ghettos were controlled and administered according to their own rules, including turning victims’ confiscated houses and shops into prisons, where they transferred detainees and tortured them. The NDF’s deputy commander of its information bureau for the NDF at the state level compared the neighborhood to the Bermuda Triangle where everyone disappears. The videos and our interviews shed light on the massive informal imprisonment campaign in Tadamon. Three of our videos show severe torture of civilian victims in private houses: beatings, lashings, burnings, electrocution and psychological torture. The perpetrators, including Youssef and Najib, inflicted cruel and experimental torture for their own amusement at the victims’ suffering. Al-Hassan was aware of these prisons and even oversaw the process and encouraged the perpetrators.

Third, sexual violence was so widespread in Tadamon that it could not have been anything other than a policy. One woman we interviewed told us that she walked to the Branch 227 office in Daboul Street to ask about her husband’s whereabouts. Youssef was sitting in his chair behind the desk, in a dimly lit room, smoking cigarettes, while torture sounds were echoing in the room behind him. He listened carefully to the woman and promised to release her husband on one condition: “Sleep with me or you can forget about your husband.” For two years, starting that day, Youssef raped this woman. Her sisters, female neighbors, and even husbands were raped and sexually assaulted by the intelligence and the Shabbiha, especially by Abu Muntajab. The Shabbiha’s systematic kidnapping and torture of men created an atmosphere of fear, and it reinforced women’s vulnerability. Women negotiated their survival by engaging in forced sexual relationships with the perpetrators — in other words, sexual slavery. Male victims experienced similar violence during imprisonment and torture. The perpetrators arrested men on suspicion of sympathy with the opposition, but they were also arrested to manipulate their female relatives.

Fourth and final are forced labor and economic exploitation. With the escalation of the clashes on the front lines in 2013, military intelligence officers as well as militia members of the NDF stationed at checkpoints arrested Sunni men from Tadamon, Daf al-Shouq and other areas, and transported them to the front lines as forced laborers to dig trenches, build barriers and construct walls as the shells and bullets of the opposition flew around them. Those who survived the hardship of work or skirmishes were shot dead in the trenches and their corpses turned to ashes. Forced labor was not only a military necessity but also a lucrative business for the warlords and intelligence commanders. To escape forced labor, civilians had to pay up to 2 million Syrian liras (the equivalent of $40,000, depending on the exchange rate, which fluctuates) to the checkpoints. Another layer of economic oppression and violence in the neighborhood was the illicit confiscation of private property. As people from the opposition areas fled to Tadamon, the real estate market became a booming business. Mukhabarat and Shabbiha commanders laid their hands on the property of evicted or killed victims and rented them out in the hot real estate market, under the pretext of helping the “martyrs” and displaced families or out of military necessity. For example, Youssef and his bosses seized at least 30 properties in Tadamon, which they are renting out still today.

The victims constituted an enormous moral and emotional burden to us. Their families and loved ones had no idea about their whereabouts. We experienced a dreadful dilemma: We knew but could not tell anyone; we wanted to identify the victims, but then we needed to show people. As we watched the videos over and over, we pondered: Would we want to see our own loved ones’ last seconds? Most of these victims were forgotten and marginalized. The international media primarily focused on the suffering in opposition territories, whereas the Assad regime covered up its crimes and imposed a deadly silence on Syrian society. As a result, even the victims became confused by the lack of acknowledgment of their pain. The shame, fear, powerlessness and continued oppression to this day led one interviewee to wonder: “Was I raped?” Our oral history interviews gave the survivors an opportunity to not only revisit their memories of violent events but also to validate their identities as victims.

These video clips are unique within the flood of violent footage emerging from Syria during the conflict: Mukhabarat officers who report to Assad, with recognizable faces, were cooperating with the Shabbiha in documenting their own crimes against defenseless civilians. Why did they do it? One the one hand, it makes no sense to lift these two shooters out of the broader context of mass impunity for the violence of the Syrian intelligence agencies and militias, for which ultimate command responsibility lies with Assad. If we take the perpetrators at their word, they saw these massacres as a sacrifice out of revenge for their fallen comrades, Hisham Issa and Ammar Abbas. Youssef openly said in the videos and in the interviews that he avenged his younger brother Naim, who had died fighting in Darayya. They filmed the whole endeavor as trophy footage but also as evidence to higher officers of having carried out the job.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.