On Monday, Dec. 9, at the Jaber-Nasib crossing between Jordan and Syria (known as Jaber on the Jordanian side and Nasib on the Syrian side), cars were parked on either side of a gravelly road, flanked by broken Jersey barriers. The scene was a mixture of anticipation and cautious excitement, the air heavy with words waiting to be said. Among those waiting on the Jordanian side of the border was 67-year-old Reda Fraihat, seated outside his car in a dark blue tracksuit and gray house slippers, a cigarette between his fingers.

Reda’s eyes darted between the black gate in the distance and his family: his sons Mohamad and Qusai, and his niece Saba, all of them adults. They were waiting for Ebrahim, Reda’s brother, to return after spending 18 years in the labyrinth of Syria’s prisons.

The border crossing had been closed for days. On Friday, Dec. 6, Jordan’s Interior Minister Mazen Faraya had announced its temporary closure, citing security concerns. But on Sunday, Dec. 8, Syrian fighters from the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) rebel faction overthrew President Bashar al-Assad’s regime in a swift takeover, sparking a wave of hope among the Syrian diaspora. For many, return suddenly felt within reach, including for Jordanians like Reda and his family.

While it remains unclear how many Jordanian citizens have been held without charge inside Assad’s notorious prisons, the fall of the regime and subsequent freeing of prisoners by the rebels have given many families hope of reuniting with loved ones. Around 1.3 million Syrian refugees still reside in Jordan, about half of them registered with the U.N. Refugee Agency. They account for almost one-quarter of the 5.5 million Syrian refugees globally.

Since the regime’s fall, movement across the Jaber-Nasib border crossing has surged. On the first day after Assad’s ouster, hundreds of Syrians returned to their homeland, according to the Jordanian publication 7iber. On Dec. 17, Rema Jamous Imseis, the U.N. Refugee Agency director for the Middle East and North Africa, stated that 1 million Syrian refugees are expected to return home voluntarily in the first half of 2025, urging states not to force their return.

Ebrahim, known as Abu Ayman, was 53 when he was arrested in 2006 in opaque circumstances. As a cross-border driver navigating the “Jordan-Damascus-Lebanon” route, he knew the roads intimately. But on that day, he became ensnared in a web of suspicion and violence that would define nearly two decades of his life.

The family’s search for him was exhaustive. Over the years, they spent more than 30,000 Jordanian dinars (around $42,300) on fraudulent promises from individuals claiming they could locate him, often chasing rumors that ultimately led nowhere. Ebrahim’s mother, his son and two brothers passed away while he remained imprisoned.

In 2010, their efforts somewhat paid off — they located him in the notorious Sednaya Prison, known as the “human slaughterhouse.” “When we visited, he wouldn’t engage with us. We would ask him how he was and he just said, ‘Good’ and ‘May God prolong Bashar’s life,’” said Reda.

Ebrahim’s ordeal began with a seemingly ordinary day. He was waiting for passengers outside a travel office in Abdali, Amman, when a young man handed him an empty bag to deliver to Damascus, according to an interview with him on Jordan’s Al-Mamlaka TV.

The request seemed innocuous. But when Ebrahim reached Syria and tried to deliver the bag, gunshots rang out. Within moments, he was blindfolded and arrested. Syrian authorities later claimed that the seams of the bag concealed a paper with “sensitive information.”

At the crossing on Monday, when asked about Ebrahim’s imprisonment, Reda’s response was: “It was all because of Bashar the slaughterer. Ebrahim was a driver, a very simple person — he was scared of his own shadow.”

In 2013, the family received another update. Ebrahim had been transferred to Branch 235, a detention center also known as the Palestine Branch, operated by Syrian intelligence and notorious for its deplorable conditions and torture.

That same year, Reda visited Syria in hopes of securing his brother’s release. At the prison, he saw Ebrahim’s car abandoned in the yard, but staff denied it was his. “The manager assured me that if I returned in 40 days, I could take my brother with me,” Reda said. “I counted down every second until I could go back. But when I tried to reenter Syria, I discovered my name had been flagged at the border — that I was barred from entering.”

On Monday, the family waited at the border for hours. At 12:35 p.m., Jordanian officials told them Ebrahim would be released in 10 minutes. Yet as the family’s wait dragged into the night, Ebrahim was yet to be released.

Jordanian authorities were conducting a series of internal security procedures before they could release him. “We waited 18 years; we can wait a bit more,” Reda said, his voice cracking. “We have trays of mansaf waiting for him at home.” Mansaf, Jordan’s national dish, is more than a meal. It is a cultural emblem served at life’s major milestones — weddings, funerals and, for the Fraihat family, long-awaited reunions.

Reda’s niece, Saba, paced the gravel, moving between her family and the border gate, her hope flickering with every car that emerged from the entrance.

“We got a call last night,” she said, one of the flurry of calls to loved ones from prisoners freed by the rebels since Assad was toppled. “A few Jordanians told us someone in Syria found him, that he is safe and free.” She held up a photo of Ebrahim at the home of the stranger who had helped him.

Ebrahim finally reunited with his family on Tuesday. He shared details of his imprisonment on national television. “I was chained in a corridor between cells, suspended from the ceiling, handcuffed and stripped to my underwear,” he said. “They electrocuted me for 24 hours straight. Then they put me under freezing air until I collapsed.”

He was put in solitary confinement, in a cell that he said was 2 meters long and 1.4 meters wide. “My room number in solitary confinement at the Palestine Branch was 31, and I stayed there for nine months. I will never forget those days,” he said in the interview. After nine months at Branch 235, Ebrahim was moved to Adra Civilian Prison, where he spent the remainder of his 18-year ordeal.

Nearby, at the border, a different story was unfolding. Noor Al-Zoubi, a young mother, was saying goodbye to her own loved one — her mother, who was returning to Syria after a decade in Jordan. Since fleeing Daraa in southern Syria in 2012, Noor and her mother have been together, her mother helping her raise her three children, aged 5, 2 and 8 months. “She wanted to see my brother,” Noor said, holding her youngest child in her arms. She, too, was referring to the recent freeing of prisoners by the Syrian rebels. “He was released two days ago. After six years of silence, we heard his voice again.”

Noor’s brother, a former “military man,” as she described him, was imprisoned for six years without trial or due process. During that time, the family was permitted only limited communication, often going extended periods without hearing from him. In the last two years, their hope flickered to life as they were allowed visits, and her mother clung to the possibility that her son might one day be freed.

“When she spoke to him after his release, she decided immediately that she would go back to Syria to see him in person,” Noor said. “It has been hard to say goodbye to her, but I can’t blame her. She has been waiting for this moment. Six years is a long time.”

The joy of her brother’s release came tempered by grim details. Over the phone, Noor’s brother told her about a day a doctor arrived in his cell — supposedly to treat his chronic back pain. Instead, the doctor ordered him to drop his belongings, then beat him on the very spot that ached, causing him to walk hunched over from the pain.

“He told me, ‘This was nothing compared to what they did to us,’” she said. “Thank God, he is released.” For Noor, the reunion had been long awaited. “It was pure joy to hear his voice again,” she said. “But my heart still aches for those who remain behind.”

Kamel Nabulsi, a Syrian Jordanian, said that he prays his father is among those who remain. For two consecutive mornings after Assad’s ouster, Kamel traveled to the Jordanian-Syrian border, riding over 40 miles on his motorcycle from Amman to Jaber al-Sirhan. At the crossing, he asked anyone who might have crossed into Jordan if they had seen or heard of Khalil, his father, who has been detained since 2013.

Kamel grew up in Syria until he was 16. In 2015, he returned to Jordan, two years after his father was detained without charge while leaving his house and walking in the neighborhood. The family heard whispers that he had been moved to Sednaya Prison from the Palestine Branch. Since then, there has only been silence.

“We had two homes then — one in Syria and one here, in Tabarbour. Life was normal,” he said. Now, his days are defined by anticipation. “We have heard nothing. Not on social media, not in the lists of names of prisoners.”

Khalil was 60 years old at the time of his arrest, a man battling a heart condition. “I am hoping he wasn’t put underground in Sednaya,” Kamel said, “because he’s an old man, and he was not armed.”

Seated near the Fraihat family, Kamel repeatedly checked his phone, a reflex born of longing. At times, he would stand, approach the officers at the gate and ask for news. He carried a photo of his father on his phone, showing it to passersby in the hope that someone — anyone — might recognize the man in the picture.

“I’m holding on to a glimmer of hope,” he said. “If God wills, I’ll find him.” A few days later, via WhatsApp, Kamel told us he had yet to hear word of his father but would keep trying.

Nearby, Baron Al-Khlaif, a 27-year-old from Homs, shared a similar resolve. He approached with quiet urgency and asked if we had a moment to listen to him. Baron was determined to cross into Syria, despite the protests of those closest to him, including his wife. “Since Hama was liberated, I have wanted to return,” he said.

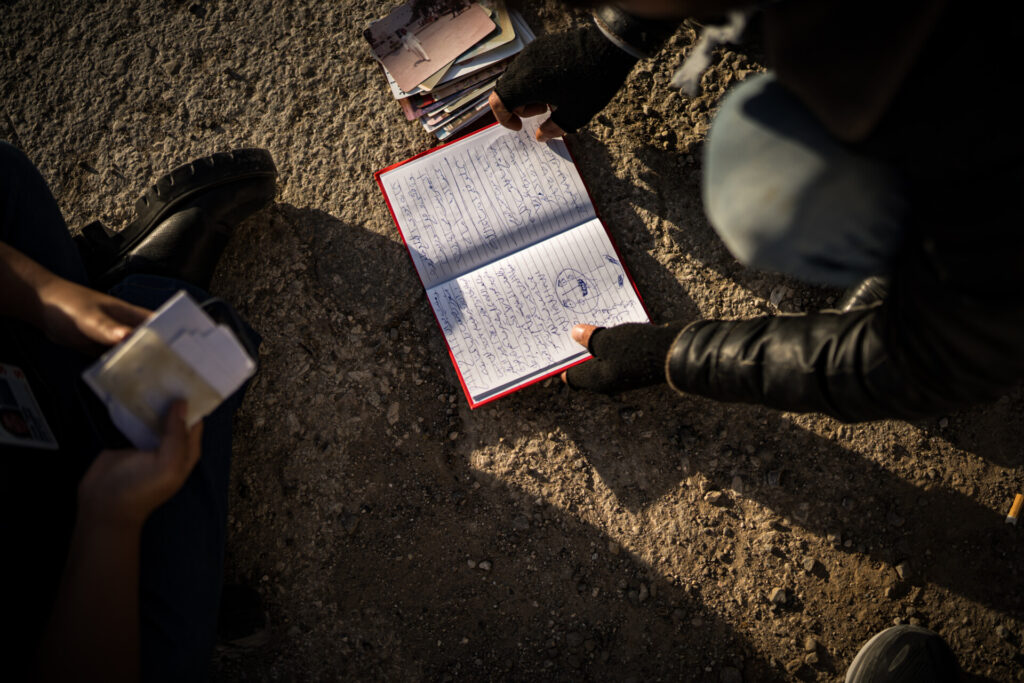

At the exit gate, he stood with little more than the clothes on his back, a thick coat to ward off the December chill and a journal chronicling his life. In his hands were scattered remnants of his identity: two empty ID cases, one that once housed his Syrian ID and another his Jordanian one. He had no luggage, no phone and no passport.

Baron had one goal — to find his father, who had been missing since the early years of the civil war.

“My wife took my passport, my ID — everything,” he said, explaining that this was in an effort to stop him from returning to Syria. “But I’ve been searching for any papers that could help me go back to Syria.”

Sitting on the ground and displaying his numerous photos and papers, Baron would point to all the half-complete paperwork he had: a photocopy of the back of his ID, a picture of a certificate of sorts that belonged to his father and a few other scattered documents.

To be allowed to travel without a passport, Baron would have to obtain a travel document issued by the Syrian Embassy in Amman. This document, or “travel permit,” would cost an estimated $50, an amount Baron did not have.

“The first thing I want to do when I get to Syria is visit Sednaya Prison to see if my father is there. I haven’t heard anything about him, but I have a feeling I’ll find him there. If God wills, I’ll find him there,” he said. “This isn’t just about me — it’s about freeing all the prisoners.”

Since November 2013, Baron had lived in Mafraq city, 6 miles west of Zaatari, the largest Syrian refugee camp in the world. While his wife and five children remained in Mafraq, citing fears over Syria’s volatile and uncertain future, Baron was undeterred, setting his sights on returning to his homeland. Unable to afford transportation, he walked the final 3 miles to the border.

“I sold a gas canister I had for cash to find a ride. My phone is broken and I couldn’t afford to get it fixed, so I’ve been without a phone for 15 days,” he said.

As he waited, Baron reflected on his journey, scribbling his thoughts into his journal: grief over his wife’s refusal to join him, memories of his father’s words written on the back of a wedding photo and hopes for a reunion with his family. “Exile isn’t easy,” he said. “I have five kids I need to take care of.”

His time in Jordan was fraught with a distant grief, as he lost his uncle and aunt, who had raised him. He also lost his oldest sister and youngest brother. “They were all killed in the massacres,” he said, referring to the early years of Syria’s war.

After waiting for about an hour, two Jordanian officers finally approached Baron. They reviewed his papers and informed him he could not enter Syria without proper documentation. He then walked away with his belongings and said he would try again. As Syria grapples with the systemic abuse it has endured under the Assad regime — industrial-scale imprisonment, executions and mass graves, the likes of which experts say they haven’t seen since the Holocaust — Baron and tens of thousands of survivors like him now hope to at least learn the fate that befell their loved ones.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.