Burkina Faso’s interim president, Capt. Ibrahim Traoré, stands at a podium listing Africa’s riches. He names them as cobalt, platinum and uranium, and then asks why the continent, the world’s richest in minerals, remains poor. It’s a passionate speech about exploitation, corruption and neocolonialism. The speech is raw and defiant, its questions pertinent.

“Africa owns 70% of the world’s cobalt reserves. Your cellphones, your computer, your electric car won’t work without cobalt. This cobalt comes from Congo, but the Congolese can’t afford cellphones,” Traoré says.

“Gold flows like rivers from our lands, but our people swim in poverty,” he adds. Then comes the punch line: “Colonialism didn’t end, it changed shape. You used to come and occupy our lands, now you come and establish companies. You used to take by force, now you make agreements. You used to rule with the whip, now you rule with credit.”

It’s a fiery speech that sounds like Traoré — but it’s not real. The entire video was generated by artificial intelligence. Traoré never gave that speech. Still, it struck a nerve. Over 26 million people have watched and shared it. Some believe it’s authentic. Others don’t care. “If this is AI,” one viewer commented, “then let AI lead us.” Another posted: “He’s saying what every African leader is too scared to say.”

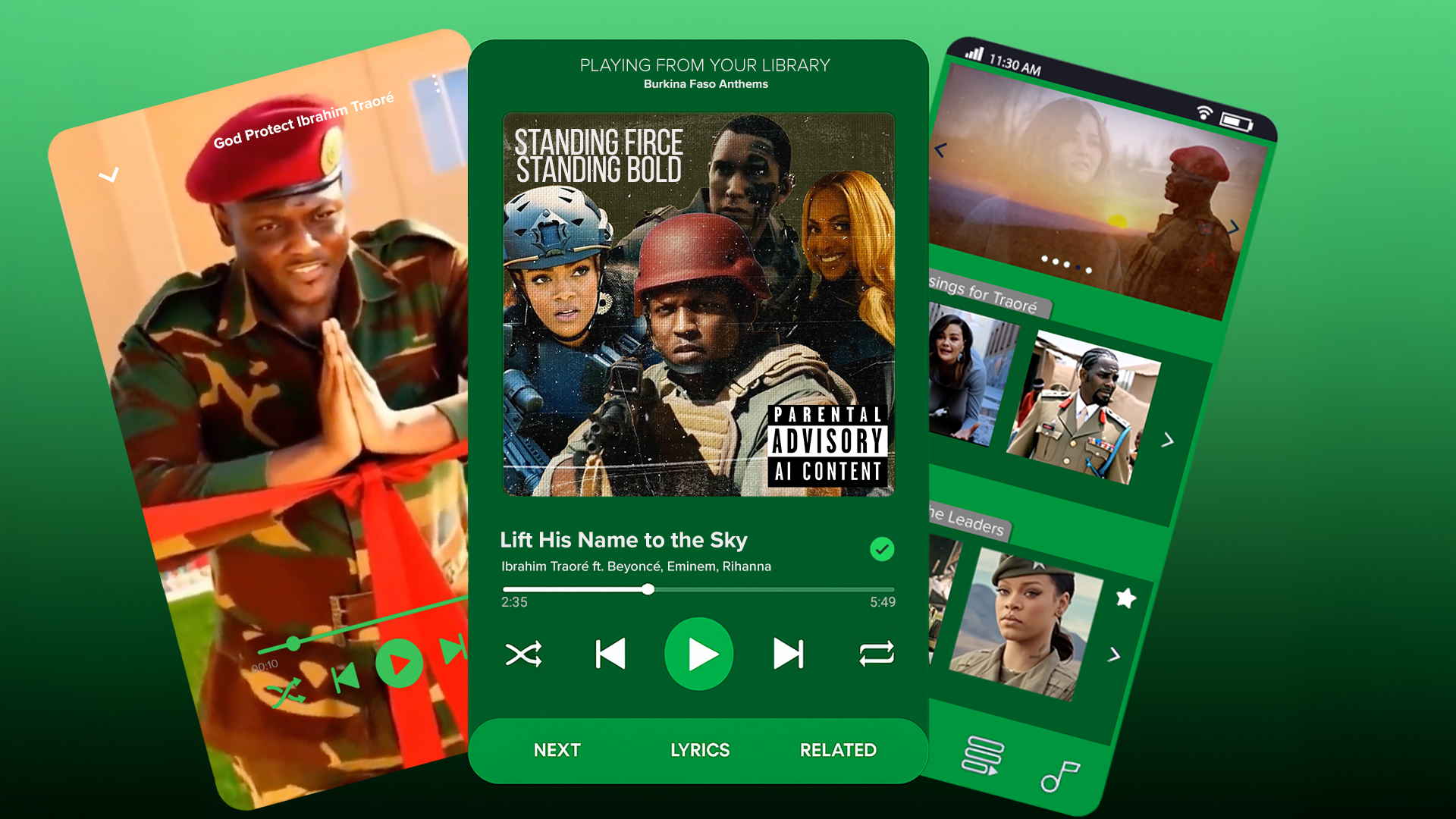

The speech is just one of numerous AI-generated videos flooding social media. And they’re not just political: They’re musical, visual and deeply emotional, and they feel real. On platforms like YouTube, TikTok and X, there’s a growing number of videos in which celebrities like Beyoncé, Buju Banton, R. Kelly, Chris Brown, Diddy and Burna Boy appear to sing Traoré’s praises in glowing terms. The music sounds eerily like the real artists. The vocals mimic their tone and cadence. The production quality is slick and the visuals are often overlaid with African flags, soldier salutes or protest imagery. But just like the political videos, the music and graphics are all AI-generated. These are not crude fakes. They’re realistic-looking deepfakes made to trigger strong emotions.

There’s a whole genre of these videos, and they’re attracting millions of views. One of the most popular is “God Protect Ibrahim Traoré, Protect Burkina Faso,” which opens with an AI-generated version of R. Kelly at a piano, dressed in black and white, singing a teary and heartfelt prayer for Traoré. The video cuts between this and dramatic clips of Traoré leading troops, standing with citizens and surviving a failed coup.

The lyrics talk about faith, sacrifice and African unity. In the song, R. Kelly is shown praying for “a soldier in a holy fight,” asking God to protect and guide Traoré. The chorus sounds like a real prayer, calling for justice and peace in Burkina Faso. Some versions also feature AI voices like that of Diddy, adding to the emotional pull.

The lyrics of these songs contain consistent themes of African self-sufficiency and sovereignty alongside religious language. The imagery is also marked by melodrama. One video features the likeness of a sobbing Selena Gomez on her knees in a bulletproof vest. Others feature famous singers like R. Kelly with their hands clasped in prayer — and militancy. A verse by AI Eminem proclaims, “they tryna paint him like a villain cuz he won’t kneel, pulling out the puppet strings make the West feel,” while another song by AI R. Kelly states that Traoré “kicked out the soldiers of the old regime, told the West we reclaim the dream.”

Some channels producing Traoré music videos of different celebrities reuse the same lyrics in different meters and melodies. The same title, “God Protect Ibrahim Traoré,” is used for several different songs with AI versions of real artists, with some receiving millions of views on YouTube.

But who exactly is the man behind the myth? Traoré came to power in September 2022 after leading a coup that ousted Burkina Faso’s then-leader, Paul-Henri Damiba. At just 34, Traoré became the world’s youngest head of state. He had risen through the ranks of the military during a time when the country was struggling to contain a growing jihadist insurgency. Once in power, he promised to restore security and reject foreign interference, particularly from the French, the former colonial rulers who still wield influence through their leftover holdings.

Now, at 37, Traoré has become one of the most talked-about leaders on the continent, building an image as a Pan-Africanist firebrand. His admirers often compare him to Thomas Sankara, the Marxist revolutionary sometimes referred to as Africa’s Che Guevara.

Traoré styles himself after Sankara, since both were young military men who seized power during national crises and preached sovereignty and Pan-African pride. For many in Burkina Faso and beyond, Traoré feels like a modern-day echo of Sankara’s legacy.

One of the reasons Traoré’s image is spreading so quickly beyond geographic and linguistic boundaries is something Sankara never had: the power of AI. There is also a stream of viral clips portraying Traoré as a fearless reformer who has stood up to France, the United Nations and other Western powers. In some, he’s shown creating smartphones, launching satellites or standing next to rows of cheering soldiers — none of which actually happened.

Nor is he the only one. In Mali, Col. Assimi Goïta, who seized power in 2021, is featured in AI-generated videos that paint him as a national savior. In Sudan, both Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and his rival, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (aka Hemedti), have been turned into digital heroes and portrayed as the “real” defenders of the country in online content, each trying to win hearts and minds in the middle of a brutal war.

The number of these videos is astonishing. New Lines analyzed hundreds of AI videos on YouTube and TikTok featuring Traoré, Hemedti and Burhan. We identified relevant YouTube channels through repeated searches, conducted over the course of several weeks, for “Traoré” and analyzed 560 videos on five channels. The top 10 most viewed videos for each account garnered a total of over 5.2 million views.

On TikTok, the views are even more astounding. New Lines identified 15 TikTok accounts featuring Traoré, 15 featuring Burhan and 15 featuring Hemedti. The 25 most viewed videos came from 10 different accounts and received a combined total of 95 million views. The top 100 most viewed videos came from 23 different accounts and received a combined total of 144 million views.

This isn’t just about deepfakes or clever editing. What’s happening online speaks to something deeper: a real hunger for strong, authentic African leadership. AI-generated videos of men like Traoré, Goïta, Burhan and Hemedti are going viral not because people are being fooled, but because they tap into frustration, pride and hope. They transform these men into heroic and larger-than-life figures. In some cases, people know the videos aren’t real, but they still share them since they speak to what many want to be true. That emotional connection is shaping how people think, who they admire and what kind of leadership they’re willing to follow, even if it’s built on fiction.

This emotional pull is not just widespread — it is deeply personal. John Mutuma is a law student at the University of Nairobi and, like many young Africans, he’s been closely following the rise of Traoré. Mutuma boasts of watching many of the viral clips online, the fiery speeches, the proud declarations, the moments that seem to capture a kind of Pan-African defiance. And they move him.

“They touch something in me,” he told New Lines. “Even if they’re not real, they speak to a truth I feel inside. I’m Kenyan, but when I see what’s happening in Burkina Faso, or Mali, or Niger, I see the same struggle. People are tired of the same kind of leadership. That’s why they connect to him.”

Mutuma said that his X account is a space where he speaks out on issues that affect people across the continent. “I try to dig deep, find out what’s really happening and share what the Western media won’t. They rarely say anything good about Africa. So when these videos show our leaders standing up, sounding strong, even if they’re AI, I get why people share them. I do, too.”

It doesn’t matter to Mutuma that some of the speeches are fictional. What matters, he said, is the message they carry and how deeply people see their own reality reflected in them.

Mutuma’s reaction isn’t unique. Across Africa and in the diaspora, many people are engaging with these videos, not as fact but as emotional truth. In a political landscape in which they often feel ignored, AI-generated clips offer something that feels honest, even if it isn’t real.

That’s what makes them both powerful and complicated. These videos blend myth, fragments of truth and history into something very appealing. Some show Traoré inspecting troops or speaking, with words from famous revolutionaries added on. Videos show Traoré delivering fabricated speeches across several different languages. The point is not to be accurate but to make people feel supported and inspired.

“There’s a real hunger for stories of leadership that feel bold and honest,” said Nanjira Sambuli, a researcher and policy strategist at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, who studies how digital technology is shaping governance, diplomacy and culture across Africa. “These videos are filling a vacuum left by broken promises. They offer people a vision, even if it’s not real,” Sambuli told New Lines.

According to Sambuli, Traoré’s appeal extends far beyond Burkina Faso. “It’s this idea that our generation is taking on leadership by any means necessary,” she said. Military figures like Traoré and Mali’s Goïta are being recast as reformers. The internet, and AI, accelerate this shift.

Yet the rise of these videos comes with real risks. Nanjira fears that in places like Sudan, where people are living through war and displacement, AI-generated clips can drown out the reality on the ground. And in Burkina Faso, where Traoré’s image is being glorified, journalism is under attack. It’s a sharp contradiction: While social media is flooded with feel-good digital heroism, those trying to report what’s actually happening are being silenced.

For Nanjira, this moment reflects a kind of online spectacle, where different actors are using whatever tools they can to control the story. And it raises deeper questions: Who gets to shape the story of Africa’s future, and what happens when fiction spreads faster than fact?

In places like the Sahel and Sudan, where conflict shapes daily life, fact-checking feels like chasing shadows, as AI-generated videos of military leaders spread fast, fuel emotion and leave little room for doubt or pause.

“We need to get access to sources” to debunk these claims, said African fact-checker Bilal Tairou in an interview with New Lines. “The challenge is that, often, sources are not accessible. Many media outlets have been shut down or forced into exile, and those in power make it difficult for anyone to share reliable information.”

According to Tairou, some of these videos are clearly part of well-organized propaganda campaigns meant to stir up anti-Western feeling or boost support for military regimes backed by countries like Russia, Turkey or Iran. But plenty of the content is also shared by regular people caught in the moment, driven by emotion and a desire to show support. Its reach has spawned a digital ecosystem and made its creation lucrative. Several accounts analyzed by New Lines offer digital marketing courses to teach others how to profit from viral AI videos. Even with all this noise, fact-checkers are still doing the hard work of putting out evidence-based information.

Paul Mucheke Wangechi is a 27-year-old digital marketer, videographer and website designer based in Kenya. A self-described Pan-Africanist, he runs a YouTube channel called The Sahel Informer. “I’m just an African crusader. I’m just trying to get the message out there,” he told New Lines over a WhatsApp call. He said AI makes it much easier and cheaper to produce content online, but added, “We have to make sure, even if you’re using AI, we don’t go overboard and try to make up things that are not there.”

Asked about the popularity of this kind of content, he said the message resonates with the desires of young Africans. “Africans have known nothing other than suppression and oppression for the longest” time, he said. “You are given this idea of independence, and you are given this idea of democracy and all these things that you have been told [like] self-sovereignty. But it’s not there,” he said.

Mucheke said he sees Traoré as part of a broader shift in the region. He expressed disillusionment with African democracies but added, “We cannot ignore the fact that military intervention is not the solution. We need better solutions.”

He said he’s not afraid to be critical of Traoré when he believes he is not fulfilling his promises or taking an authoritarian turn but that, so far, he is doing a good job. “Time never lies. Time will tell us the truth about Traoré,” he said.

The real danger isn’t just the spread of misinformation but how it quietly shifts the sense of what strong leadership looks like. In times when many, especially the young, feel ignored or failed by traditional politics, narratives that center on heroic leaders using force, defiance and control start to feel like strength.

Traoré is shown over and over again as a savior leading his troops and providing services that do not exist. What keeps this savior image alive, however, isn’t truth, but the way it allows people to project their hopes and desires onto a heroic figure who comes to embody the state. His success became Burkina Faso’s success and, perhaps, that of the continent.

Journalist Samira Sawlani described to New Lines how her friends and acquaintances in Kenya — mainly people who are far removed from politics — repeated lines they’d seen on WhatsApp or Instagram about Traoré “bringing real change.” Even her landlady, a woman in her 60s, said she wished “we had someone like that.”

According to Sawlani, this kind of distortion has consequences. The more viral these stories become, the harder it is for reality to cut through. “You’re seeing these glowing stories about these men, but no one’s talking about what’s actually going on,” Sawlani said. “It’s almost blocking out the news we should be getting about conflict, displacement, school closures and people dying.”

And the danger, she says, isn’t just misinformation. It’s the rewriting of what strong leadership looks like. “He came into power through a coup,” Sawlani pointed out. “But now that we’re being fed all these so-called successes, it starts to sound like democracy is overrated. Maybe it’s better to have a military government that tells the French to get lost.”

And this shift in perception isn’t happening in a vacuum; it’s landing hardest on the generation most plugged in and most disillusioned. It is young people, especially in places where coups have taken place or civil protest is bubbling, who are most vulnerable to this flood of misinformation. In countries like Burkina Faso, Mali, Sudan and even parts of Nigeria and Kenya, viral content doesn’t just travel fast; it sticks. That’s partly because many of the people consuming it have little experience filtering fact from fiction. The line between political reality and digital spectacle is blurred and there’s not always a toolkit to sort it out. Conflict creates an environment of confusion in which falsehood is able to flourish.

Tairou explained how AI-generated content and social media virality are helping to construct a new kind of hero in fatigues, one that feels familiar, even aspirational. “These videos of military leaders, often dressed in ceremonial uniforms or surrounded by crowds, are made to look like moments of destiny,” he said. “They speak directly to people’s frustration with democracy and decades of broken promises, and in places where schools are underfunded and traditional media has been silenced, that imagery becomes powerful, especially for the youth.”

He added that this form of digital mythmaking rarely holds up under scrutiny. “In Burkina Faso, for instance, Traoré is portrayed online as the one who’s standing up to the West and taking charge, but when you look at the data, insecurity has worsened, and his popularity isn’t as deep as it seems,” Bilal said. “It’s mostly emotional appeal. Social media has just made a small message look louder than it is.”

Folahanmi Aina, a political scientist and security analyst at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, takes this concern further. He warns that young people, especially those lacking the critical skills to verify what they see online, risk seeing dictators like Traoré as heroes and role models. This, he says, normalizes authoritarianism and blinds many to the long-term damage such leaders inflict on peace and stability.

“Leaders like Traoré need to be seen for what they really are — dictators who have dismantled democracies and set back progress by years,” Folahanmi told New Lines. “The viral spread of their digital image only amplifies this false narrative.”

Yet, Folahanmi points out, this reliance on digital propaganda also reveals a sense of desperation. Real security and governance continue to decline under these regimes, even as the online personas of their leaders grow stronger. He adds that while some rural communities — driven by anti-Western sentiment and distrust of elites — may express solidarity with these leaders, the broader appeal is limited mostly to countries where coups have taken place.

The danger, he warns, is that this digital mythmaking can convince a generation to accept authoritarianism as normal, overlooking the real costs to democracy, peace and development. “This is not just about fake videos or social media hype,” Folahanmi said. “It’s about the rewriting of political reality in ways that threaten the future of the continent.”

What’s unfolding in Africa, particularly in the Sahel and Sudan, isn’t just a wave of misinformation; it’s a shift in how some people understand authority, leadership and belonging. The content being shared online is shaping perceptions in real time, especially among younger audiences who feel ignored by political systems. As fact-checkers and journalists try to keep up, the stakes remain high — not just for truth, but for the kind of leadership Africans believe in going forward.

“This digital mythmaking risks drowning out the harsh realities on the ground,” Sawlani warned. “People are still dying in these conflicts, but the stories we see online often block out those truths. If we lose sight of what’s really happening, the consequences for peace and stability will be serious, and this will deeply affect Africa’s future.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.