Letisia Nghiondjwa and her husband live at the foot of a dumpsite, deep inside the slums of Havana, one of Namibia’s largest informal settlements on the outskirts of the capital, Windhoek. She carries a tin pot full of fat cakes, a greasy Namibian sweet treat similar to a doughnut or fried bun that she sells at the market alongside hundreds of others touting clothes, groceries and assorted miscellaneous goods. The fat cakes are delicious, but this isn’t the life Letisia had in mind.

She hails from Okanguati, a village in the Kunene region in northern Namibia, where subsistence agriculture has sustained communities for generations. Maize, millet and melon crops are adapted to the region’s arid soils, but even the savanna has its limits. In 2012, the worst drought in a generation hit Kunene hard. Two years of failed rains left plantations in ruins and dry water holes decimated livestock. That’s when Letisia and her husband came to Windhoek.

“There’s nothing left in the village,” she says. “We moved here for a better life, to find work and generate an income. Here, I make money selling fat cakes and meat. It helps keep us going.”

But the slums are a world away from the sprawling plains that Letisia knows.

In 2019, Namibia’s President Hage Geingob said living conditions in Namibia’s informal settlements were “unbearable” and constituted a “humanitarian crisis.” The arid scrubland is draped in corrugated iron as Namibians squeeze into shacks flanked on all sides by neighbors or the banks of landfill. Water is scarce for those who can afford it, while toilets are a luxury enjoyed by less than half the population. Such levels of privation not only deny Namibians access to even the most fundamental rights but also create danger in their absence.

An estimated 45 tons of feces are deposited each day in Windhoek’s informal settlements alone. Men and women in search of privacy and dignity away from the clusters of shacks are vulnerable to assaults, robbery and rape, and those afraid to go out at night use buckets inside the home instead. Others relieve themselves in plastic bags and discard them on streets, alleys and even rooftops. When the rain falls, sludge pours through neighborhoods.

A deadly four-year outbreak of hepatitis E, which started in 2017, was spread by open defecation and hit these slums the hardest.

“It is not really like being in the city,” says Letisia, whose husband is unemployed. “When the municipality burns the waste, it’s difficult to breathe. There are no jobs. We are struggling. … But we cannot go back.”

It’s hard to imagine how this could be the lesser of two evils, but people need to work. Namibia has declared four national emergencies since 2012, each due to extreme drought events. In 2019, the nation experienced its lowest rainfall in 90 years. More than 500,000 Namibians were affected by water shortages and food insecurity, while 60,000 livestock perished, and so tens of thousands of Namibians have trodden the same path as Letisia.

“People are moving for better living conditions but there is no difference,” says Lukas Shilongo, 21, a neighbor of Letisia’s who has spent his whole life in Havana. “There are not enough jobs, the people around here are self-employed, they are selling on the road. The dumpsite is growing, it is moving towards the people and it’s going to make them homeless.”

President Geingob has promised to rid the nation of these shacks by 2024, but the former mayor of Windhoek, Sade Gawanas, says they are still growing by 10% each year in the capital. Namibia’s Minister for Health, Dr. Kalumbi Shangula, also admits that the city is not keeping pace with the rapid growth of its informal settlements as drought devastates rural Namibia. “We have had droughts over many years, one part of the country is always in drought,” he says during an interview with New Lines. “Climate change is a big challenge. We are paying for it, although we are not contributing to it.”

Rural Namibia is still home to over 1 million citizens, although that number is declining. And the changing climate is forcing many who stay to adapt. A Red Cross assessment found that drought had forced some families in northern Namibia to adopt a semi-nomadic existence in search of fresh pasture or water.

Xhuka Shorty and his family are all Ju/‘hoansi, a group indigenous to southern Africa, also known as Bushmen. He was 98 years old when he and 12 members of his family were evicted from the farmstead where he had lived and worked for generations. Surviving on his monthly pension of 1,300 Namibian dollars ($87), they migrated to Katumba village in northwestern Namibia, where they lived under the shadow of a tree for eight years.

His children and grandchildren live off veldkos — food gathered from the countryside (literally “bush food” when translated from Afrikaans). But as drought increases competition for water and grazing land, human-wildlife conflicts can also arise.

“We had to move here because elephants destroyed our water tank,” says Shorty.

Indigenous groups from the north like the OvaHimba, Damara and Herero, who have traditionally relied on livestock and crops on communal land to both generate income and feed their households, are also vulnerable. Below-average rainfall has meant families spend more time searching for water than on income-generating activities. Families are reducing the number of meals they eat, as well as selling their remaining livestock and saving on school payments by withdrawing their children.

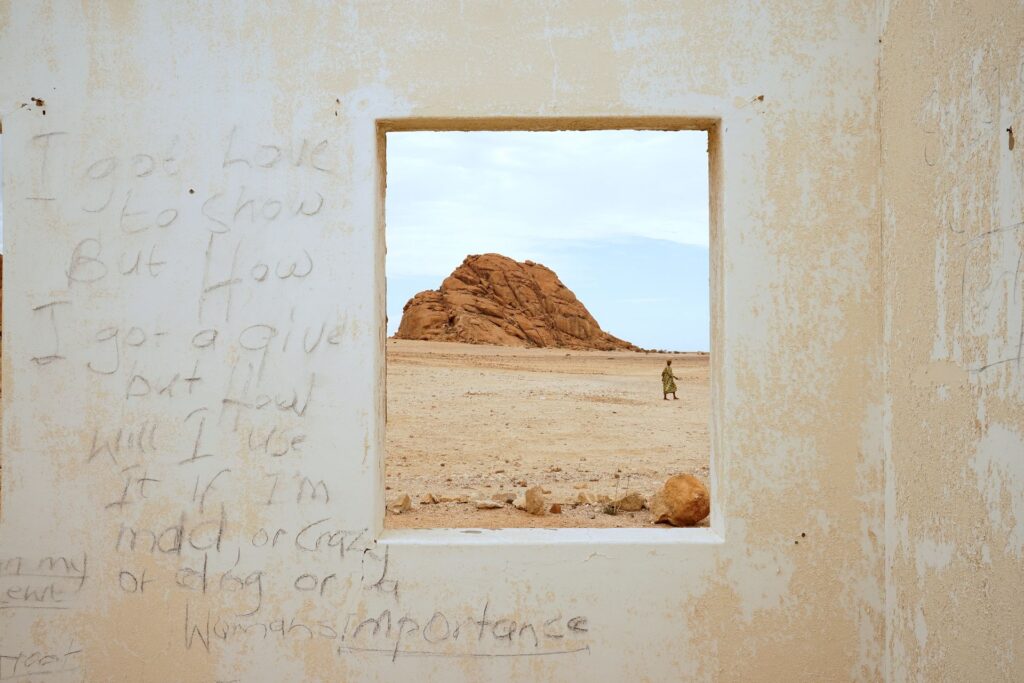

Susanna Uri-Khos and her family are Damara, but she has rejected the slums in favor of surviving in the desert. She lives on a farm with five of her sons close to the village of Spitzkoppe in the Namib, the oldest desert on Earth, boasting some of the world’s highest dunes, sculpted by fierce coastal winds for over 55 million years. Her farm enjoys spectacular views of the monumental granite peaks of the Spitzkoppe mountains, one of Namibia’s most popular tourist attractions. It’s a remarkable place to call home, and a difficult place to survive.

Susanna is frail and her farm is starved of moisture. She lost all her goats and donkeys to drought, and instead raises chickens and pigeons for their eggs. A bathtub held on scaffolding serves as a rain-fed shower and water catcher, but recently she’s reverted to carrying buckets from the borehole pump almost a third of a mile away.

Still, she won’t move to the city. Two of her other children have moved to the Democratic Resettlement Community, a vast informal settlement on the outskirts of Swakopmund by the coast, where some 20,000 Namibians live without running water or sewerage. “In 18 years in Swakopmund they’ve never got a house or a plot,” says Susanna. “They had to build their own shack. Here on the farm life is easier and safer.”

Her belief speaks to the squalor of the slums, but it’s an extraordinary claim given the whereabouts of her other sons. Five of them dropped out of school to help support the family and now leave home for weeks at a time to dig for semiprecious stones on Mount Erongo or Brandberg Mountain.

They sleep in caves at night and mine during the merciless heat of the day, drawing water from whatever dirty puddles and ponds they can find. But the road to Spitzkoppe offers up curious tourists, and they will buy the stones. This is how they make a living.

“They will never leave the farm,” she said. “It is the only livelihood they know and trust. To be self-sufficient and not rely on others.”

Susanna is the same and, despite the ceaseless austerity under which she survives, it is hard to imagine her trading this in for a shack in a slum. But there are ever fewer opportunities for those unwilling or unable to mine for semiprecious stones.

Fifty families used to live on farmland surrounding Spitzkoppe. Now, just five remain. Drought has gripped this desert, making life in the most hostile places even harder. And there’s no end in sight.

Temperatures in Namibia are set to rise much more rapidly than the global average. Researchers at the University of Cape Town estimate that for every 0.5 C increase in global temperature, temperatures in Namibia will increase by an additional 0.5-1 C. As countries worldwide commit to efforts limiting average global temperature rises to 1.5 C, Namibia looks set to break that threshold, meaning rural life will face even greater challenges.

“If the January rains disappear, then we are doomed,” says Simon Dirkse, head of climate at Windhoek’s Meteorological Institute. “Seven of the last 10 years were bad years and nobody thinks the country is going to get wetter. … We expect the droughts to become more frequent and severe. … Everyone is looking at survival, we are not taking care of what is happening in the environment. We are not adapting.”

From all quarters of Namibia’s politics there are calls to prioritize development in rural areas to help residents cope with the impacts of drought. “Most of the wealth is in the urban areas, in the rural areas there is basically nothing,” Shangula says, acknowledging that migration to larger settlements cannot be stopped until conditions are changed for rural citizens. “The people are many, and the opportunities there are not enough.”

In 2021, the government launched the Namibia Water Sector Support Programme, a massive infrastructure project aimed at improving water security for 1 million Namibians by the end of 2026, funded by a $121.7 million loan from the Africa Development Bank. But Luckson Zvogbo, who worked for the Africa Development Bank as an environmental consultant on the NWSSP, is critical of the scheme’s capacity to adapt to climate change.

“People at the forefront of the project didn’t have a very good understanding of the impact of climate change,” he says. “They are talking about increasing groundwater extraction … but if you increase groundwater extraction in an area with reduced rainfall the groundwater will eventually run out.”

Namibia’s Minister for Agriculture, Water and Land Reform, Calle Schlettwein, accepts that Namibia’s water sector is vulnerable to decreasing annual rainfall, but insists that his ministry is prepared for the impacts of climate change. “It is envisaged that accelerated development of climate resilient water resources infrastructure will mitigate against the effects of floods and droughts,” he says.

But after almost two years, the NWSSP remains in the planning and design phase and so the scheme is yet to make an impact on those who need it most.

Hamutenya Kasian is the headman of the Mile 10, Kanguni and Musitu villages in Kavango East, not far from the border with Angola. He waits patiently for his pension to arrive in a government truck, along with hundreds of other senior citizens gathered by the side of the road.

”My people have no electricity, no toilets, and there is not enough water,” he says. “They are leaving for the towns, especially the young people, they are tired of facing these challenges. … We need the government to help us.”

For now, the city, the slums and the economic opportunities they offer are not just tempting, but inevitable. Selma Mpasi, 21, cradles her 2-year-old daughter under the shade of a tree on the outskirts of Mile 10 village. She is selling oranges by the side of the road, but the baskets are full. Nobody is buying.

“Usually (by November), we are already done preparing the land, harvesting and soon to start weeding,” she says. “But we no longer receive as much rain as we used to.”

“I think life is better in Windhoek.”

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.