On the outskirts of the city of Van, in eastern Turkey, the concrete buildings of the urban center give way to small stone houses. A large field of dry thistles spreads out beyond the buildings, with scraps of clothing and backpacks scattered amid the undergrowth. There, at the bottom of a valley, about 15 young people gathered in several groups around bonfires. “Don’t take pictures!” several of them shouted at me. “Every time the press comes, the next day the police arrive, and we need to hide.”

Their fear was understandable. Most of them were migrants from Afghanistan and Pakistan who had been living in this spot for about 20 days. Some of them showed signs of physical abuse, with broken lips and burn marks on their skin. Most agreed to talk to me on the condition of anonymity.

“At the border, the Turkish police broke our phones and beat us. Several of us managed to escape and ran for two hours until we arrived here,” said one 22-year-old Afghan, who had a scarf wrapped around his injured left ankle. He had crossed on foot from Iran with a group of 100 other migrants through the Zagros mountain range. Like a lot of the people who end up in Van, he arrived in Turkey with the intention of going onward to Europe in search of paid work.

Another Afghan, Habib, had worked for two years as an interpreter for U.S. forces during the war. Fearing Taliban reprisals, he left his family behind in his homeland and paid $1,500 to get to Van. Age 35, he claimed the Turkish gendarmerie stole another $350 from him that he had intended to use to go to Ankara. “I have to get to the American embassy,” he told me.

Desperate to leave their homeland and short of money to secure a safer passage, many Afghan migrants who want to reach Turkey turn to smugglers who use perilous routes that take them through the mountains and deserts of Iran. Deaths are common during the long, exhausting journeys. Some of the victims are laid to rest here in Van’s Seyrantepe cemetery, their graves marked by nameless headstones. The fates of others are lost to history or known only through grim statistics.

Since August, the Turkish coast guard has been patrolling the huge local lake in Van, where 60 migrants — most of them Afghans — died in a shipwreck last year. The patrols are unlikely to deter more from trying to come here in search of a better future.

People smuggling is big business. According to government officials in Van province, more than 1,200 smugglers have been arrested in the area this year, the majority of them Turkish nationals. Now there are fears that the situation for Afghan migrants is nearing a tipping point that will make it harder and more dangerous for new arrivals hoping to get to Europe.

Turkey is already home to some 3.5 million Syrian refugees and, amid rising anti-immigrant sentiment, the government has repeatedly warned that it will not let the country act as a clearinghouse for the European Union. At the same time, large numbers of Afghans have been arriving since the fall of Kabul to the Taliban on Aug. 15.

Some fled their homeland fearing for their lives; others came in search of employment and greater social freedoms. The Taliban government has announced an amnesty for its domestic opponents, including anyone who worked with U.S. troops. But many Afghans had already made up their minds to leave, exhausted by decades of war and broken political promises.

According to the Turkish Interior Ministry, around 46,000 Afghans have entered Turkey illegally this past year. The construction of a concrete wall along the border with Iran is intended to curb further arrivals. “In Van province alone, we have completed 15 kilometers [9 miles] and hope to reach 64 kilometers [40 miles] before the end of the year,” said Mehmet Emin Bilmez, the local governor. Construction work, which includes the laying of concrete blocks 10 feet high and 9 feet wide, has intensified in recent months in order to make the border “impenetrable,” he said.

In the past three years, Turkey has deployed additional reinforcements of gendarmerie and special police to secure Van’s border with Iran. The EU, meanwhile, has financed the building of 103 control towers equipped with radar systems and thermal cameras along the border. “In the last year alone, we have blocked 91,000 border crossing attempts with the help of our drones and thermal camera systems,” said Bilmez.

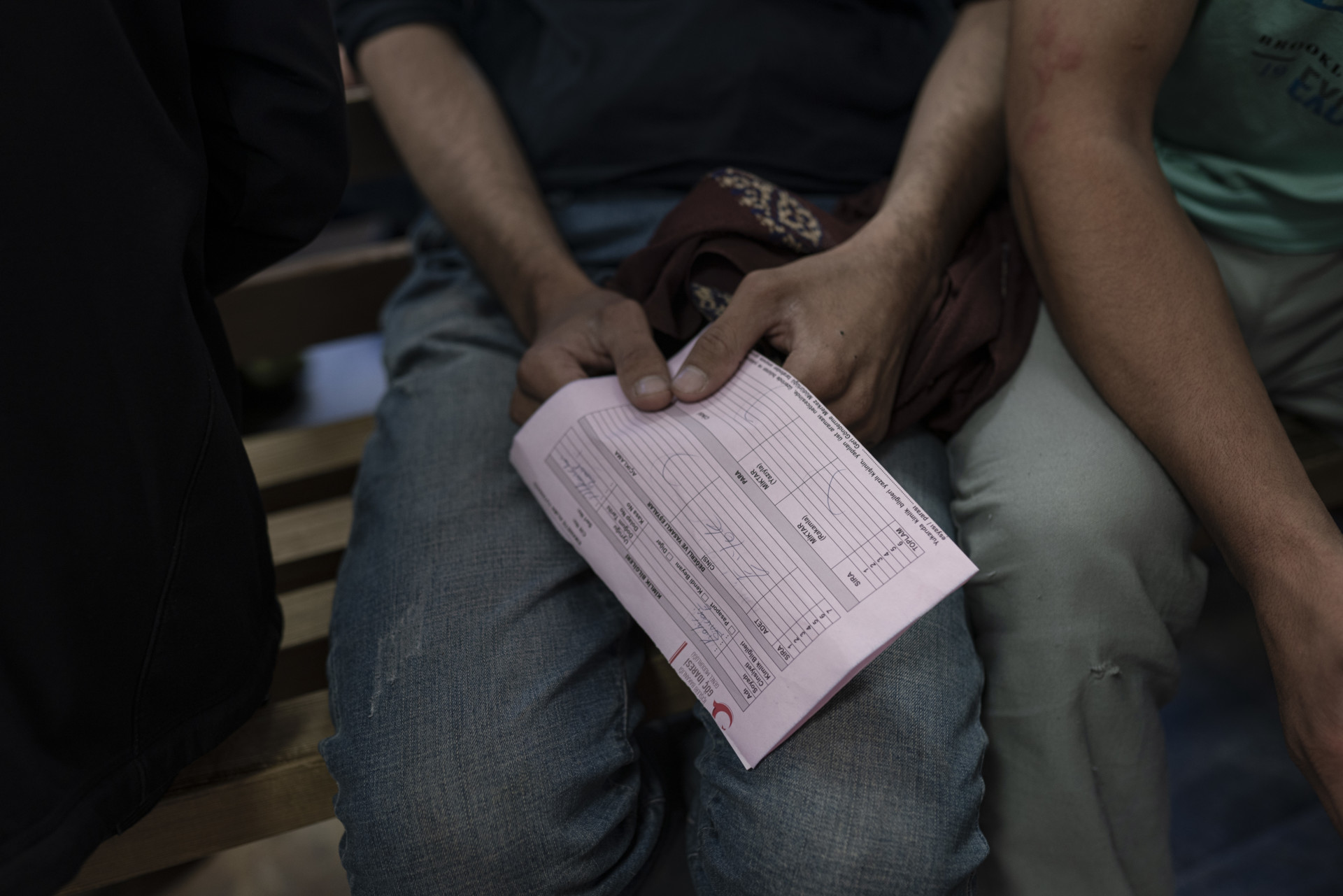

Turkey has granted its Syrian migrants special status, giving them access to some basic services. But Afghans and other refugees fleeing conflict must apply for international protection and wait for a third country to accept them. In 2018, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees gave the Directorate General of Migration Management, which is run by the Turkish Ministry of Interior, responsibility for determining applications for international protection. The number of asylum requests it processed and accepted decreased by 92.5% in the first year.

Many Afghan migrants are detained in places like the Kurubas detention center until their status is resolved. Designed to hold 750 people, it currently holds more than 1,000, according to a local human rights group. One Afghan mother detained there told me she had paid three different smugglers to bring her from Afghanistan with her seven children after the Taliban killed her husband. She said she had not seen her children for 40 days but did not reveal if they were in hiding, perhaps fearful of speaking too openly in the confines of the detention center.

According to Cuma Omurca, director of the migration department in Van province, the last deportations of Afghans took place about 10 days before the fall of Kabul to the Taliban. Those who remain on the run in Turkey know they could meet the same fate if they are arrested.

Asylum applications submitted by Afghans are rarely processed, said Mahmut Kacan, a lawyer specializing in refugee and asylum cases. “A few weeks ago, an NGO transferred me a case of three Afghan girls held at the Kurubas center,” he explained. “When I contacted the management, they denied that these women were detained there.”

Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has urged EU countries to take responsibility for the flow of migrants from Afghanistan, but the opposition Republican People’s Party has tried to portray him as weak on the issue. In August it hung a huge banner reading “Borders Are Our Honor” outside its headquarters in Ankara, hoping to capitalize on anti-refugee sentiment that has built up in recent years on the back of high unemployment and inflation rates.

Back in Van, meanwhile, the Afghans are bracing themselves for what could be a particularly harsh winter. “Last winter several bodies were found buried under the snow near Caldiran,” said Mehmet Karatas, a local human rights worker. “There are many accidents due to the conditions in which the smugglers transport the migrants.”