It has been 26 years since the passing of my beloved grandfather, Abdullah Al-Sallal, or how I call him, Jeddou. Although I was a child at the time, I still carry vivid memories of him with me. The most precious is of him gently pinching the baby fat on my hand.

I grew up listening to many stories about Jeddou’s valiant character, profound love for his country, and witty sense of humor. His kind smile never parted his face, his eyes always reflected compassion, strength, and deep contemplation, and he was able to laugh even during the most trying of times. I remember him as being tall, with a round stomach, a gray moustache, and goatee. He had square glasses and always wore a white koufeyya (a round, embroidered Yemeni headwear) with a sophisticated gray suit and tie, for when he went out, or a white thawb (a long, traditional Yemeni tunic) with a buttoned-up cardigan when he was at home.

Jeddou, the first president of North Yemen, lived a long life filled with sacrifice, imprisonment, blood, tears, and ultimately triumph and victory, all for the greater welfare and prosperity of his beloved home, Yemen. And although my time with him was short, I am grateful that I was able to witness the last few pages of his life story before he moved on from this world.

Jeddou was born in the village of Shaasan in 1917. Shaasan is a branch of the ancient and widely spread tribe of Sanhan, located southeast of Sanaa. I can imagine him as a child playing with his siblings among cubic houses that look like they were built with pieces of stone Lego, surrounded by lush trees and carefully sculpted mountains. It was a simple, but perfect, life.

However, soon after the family moved to the city of Sanaa, Jeddou lost his father, Yahya. As a result, he was enrolled in Dar Al-Aytam orphanage school in 1929, where he completed his elementary education while being raised solely by his loving mother. He then moved to the city of Al Hudaydah, southwest of Sanaa, where he completed his secondary education.

Jeddou first traveled outside of Yemen in 1936 to complete his military education in Baghdad. He graduated two and a half years later, earning the rank of second lieutenant. This chapter of his life marked a critical turning point when his dream and vision for a better, modern, and progressive Yemen was born.

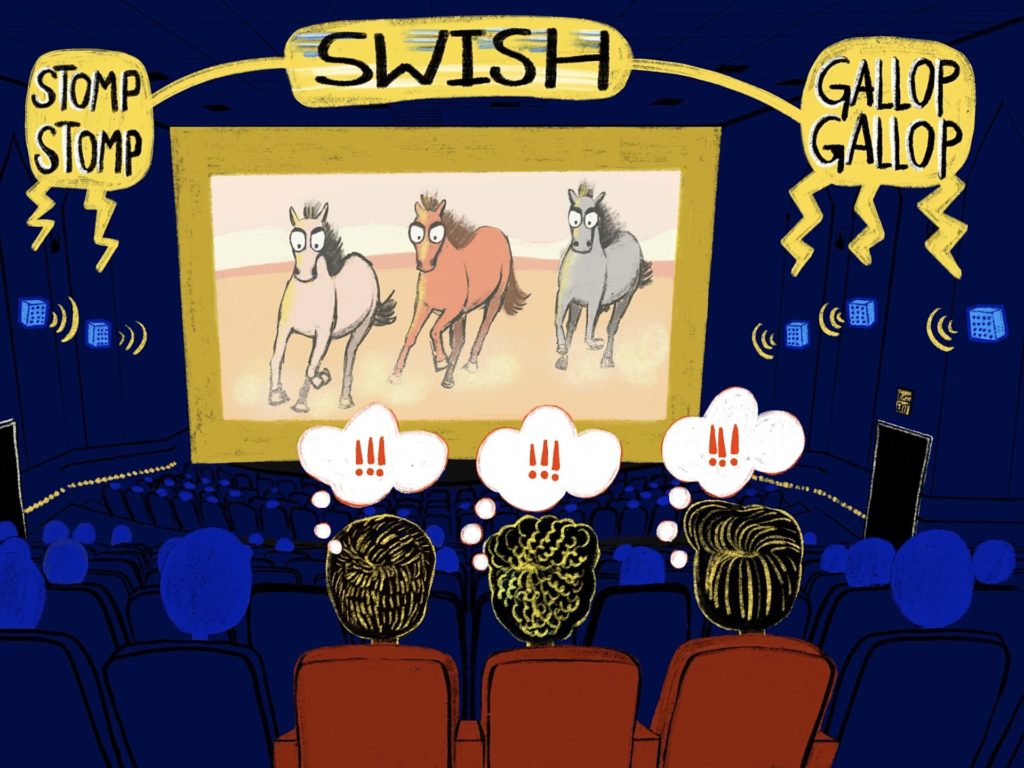

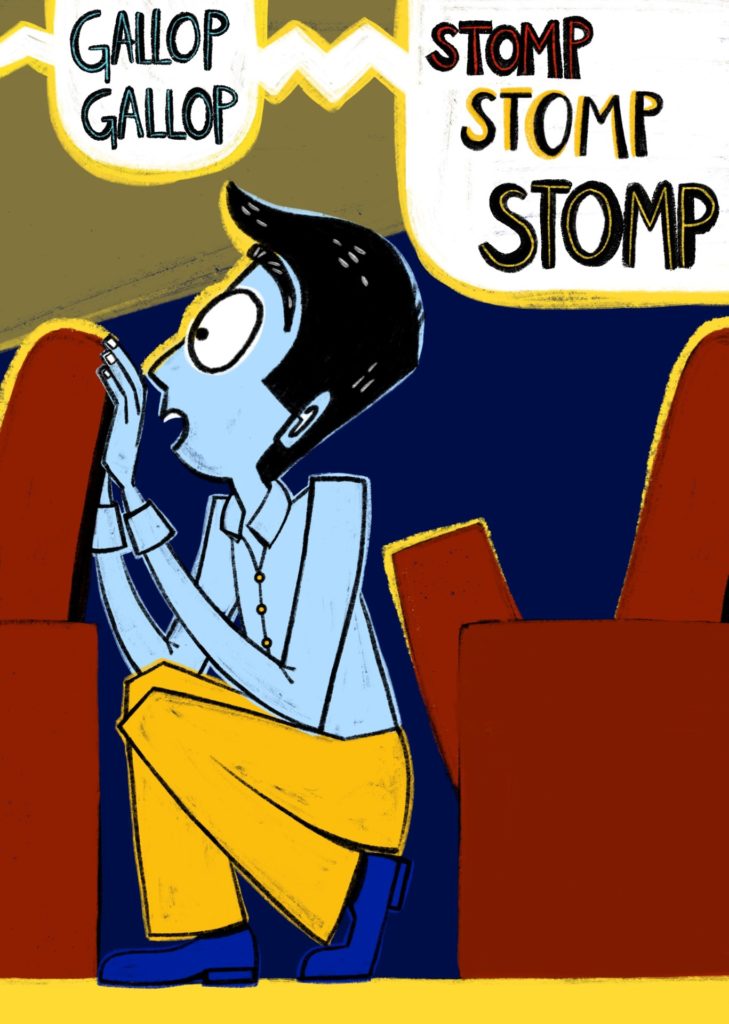

On his way to Baghdad, Jeddou made a stop in Aden before boarding the ship that would take him to Iraq. He was stunned at what he saw in the city of Aden with its cinema and modern amenities. Because of British colonization of the city from 1937 to 1963, the level of development in Aden far exceeded that of Sanaa, leaving Jeddou with the feeling that he had stepped into a different country. Jeddou recalled his first experience of the cinema in Aden as being startling: When he saw horses running across the screen, he thought they were real.

When he reached Baghdad, he was, yet again, flabbergasted by the stark difference in the quality of life between Iraq and Yemen. These two trips inspired Jeddou to visit other Arab countries, such as Egypt, Palestine, Syria, and Lebanon. It seemed that any Arab city in the region had basic necessities that Sanaa lacked, such as asphalted roads, electricity, cars, and access to free health care. During his time abroad, Jeddou embarked on his first train ride with his peers. The experience was exhilarating, and being teenagers, they playfully ran back and forth in the aisle.

Still, the lack of development in Yemen compared to its neighboring Arab countries left Jeddou feeling heavy-hearted. How could a country considered one of the oldest centers of civilization in the world reach this state? Yemen was home to three powerful and affluent empires: Sabaean, Minaean, and Himyarite. This was the land that was dubbed “Arabia Felix” by the Romans, with its lush greenery, fertile land, and rich profits from its trade of frankincense, spices, and agricultural products. After having seen what was possible, my grandfather was determined to spark a change and pull Yemen out of its isolation and prehistoric way of life.

He and his partners began raising awareness about the poor conditions of the country and the dire need for change. They held meetings and discussions with other military officers, published newspaper articles, and even formed a secret alliance called the Free Officers. Yemeni civilians started listening, and the following for this new liberal movement started growing.

Many religious members of the palace attempted to convince Imam Yahya of the city’s grave conditions, but to no avail — he turned a blind eye, ear, and heart. This caused acts of rebellion: Handwritten notes condemning his oppressive rule were scattered throughout Sanaa, with some landing within the bounds of the palace walls.

Jeddou was falsely accused of writing and spreading these notes, and as a result, was captured and placed in solitary fort confinement for one year. This imprisonment marked only the beginning of a long and dark series of encounters in which Jeddou endured some of Sanaa’s darkest and most horrific prisons.

Jeddou’s years in prison didn’t alter his vision; they empowered him to try harder. He secretly continued his work with the Free Officers, and over the next few years, a number of different political parties associated with this new liberal movement started sprouting across Sanaa and Aden. Change was on the horizon.

The Free Yemeni Movement began designing the scheme for their first uprising, the Revolution of Feb. 17, 1948. With Vice Imam Abdullah Al-Wazir as their ally, they peacefully called for a reformed constitutional Imamate with Imam Yahya remaining as governor and spiritual leader but with limited, temporal powers. Unfortunately, the Imam instigated a battle that ended in his assassination. His son, Imam Ahmed, subsequently came into power, capturing and executing a large number of Free Officers.

Jeddou was then detained again. Along with his allies, he was thrown into one of the cruelest and most demoralizing prisons that existed in Yemen, perhaps the world: the dark, underground prison in Hajjah where Jeddou spent seven long and terrifying years.

The prison was a grotesque place where death and infestations thrived in every nook and cranny. Each new beheading was celebrated with loud, ghastly music that reverberated throughout the prison, serving as a chilly reminder of the horrific doom that awaited most of those who lived there. One fateful day, Jeddou’s old and dear friend, Ahmed Al-Hawrash, whom he met in Baghdad, woke up and cried, “I had a dream that they cut off my head in a large field! Me and three of my friends! I could see my head flying, then landing on the floor next to the other three!” Everyone started panicking, running, and saying their final prayers.

Ahmed walked up to Jeddou and gifted him his only pair of shoes, “You were not in my dream, they are not going to kill you.”

Moments later, sinister music and drums started playing, announcing the beginning of the execution ceremony, which was to be attended by Imam Ahmed and hundreds of spectators in a large square. The deathly musical was then silenced by the creaking of the prison doors being unlocked, and through the opening the large silhouette of the chief guard slowly appeared. He looked at Jeddou and silently signaled for him to approach. Jeddou was perplexed, “Me?” he asked. The guard responded with a head nod, yes. “You mean me? Me?” Jeddou asked again. “Yes!” shouted the guard. Jeddou turned to his friend and jokingly said, “Hey Ahmed, I have preceded you in the return to our merciful Lord, so now you can take your shoes back, they have cost me my life!” In that instant when Jeddou called his friend by his name, the guard realized he had summoned the wrong person. He asked Jeddou, “What is your name?” “Abdullah Al-Sallal,” responded Jeddou. “I am here for Ahmed Al-Hawrash,” demanded the guard.

And just like that, Jeddou’s life was spared because a pair of shoes were gifted to him by his dear friend, who died on that fateful day.

Even as Jeddou was about to answer the call of death, he was still able to find something to laugh about to fight the fear of such a distressing situation.

Imam Ahmed formed a new government that consisted of him as the king and his son Imam Badr as the crown prince, deputy prime minister, and minister for defense and foreign affairs. The rest of the government positions were distributed among Imam Ahmed’s supporters.

Upon his release from prison in 1955, Jeddou was appointed as commander of Imam Ahmed’s Private Guards. Seeing the hopeless state his country was in, he was filled with despair and sure the Imamite system would stubbornly cling to its old ways. Every second, the prying eyes of the kingdom watched as he tried to readjust to normal life. Still, he secretly continued his mission to free Yemen from the regime’s shackles.

During the mid-50s, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser was advocating for Arab unity against Western colonizing forces in the region. He sought a partnership with Saudi Arabia and Yemen, and although Imam Ahmed was against Egypt’s political thinking, he saw this as an opportunity to restrain British forces that were growing beyond Aden.

Hints of progressive change started appearing across Yemen. The Imam started permitting the establishment of new schools and colleges such as the Military College, the Police College, and the Aviation College. Luckily, Jeddou was assigned to supervise the Al-Badr Regiment. He saw this as an opportunity to spread national awareness among Yemen’s younger generations by educating them and sharing different types of publications that instilled the teachings and values of the Free Officers.

While Imam Ahmed was receiving treatment abroad for some health complications, Imam Badr attempted to prove his capabilities as a nonviolent leader and started preaching for national improvements and reforms. He made promises that included raising the army’s salaries and providing free health care.

As soon as news of these promises reached Imam Ahmed, he rushed back to Yemen, furious and threatening all those who called for, or participated in, any kind of reforms. A new wave of suppression and terror followed. A series of unjust arrests were made, and countless innocent supporters of the Free Yemeni Movement were thrown into jail, mutilated, or beheaded. Those heads would then be donned on long sticks and paraded throughout the city or hung on the walls and Bab Al-Yemen, the main gate of Sanaa.

Luckily, Jeddou was not arrested, but he was removed from the military field and placed in an administrative position as director of Al Hudaydah Port.

As 1961 approached, schooling and education in the north were still underdeveloped. Electricity was scantily introduced in Sanaa, Ta’izz, and Al Hudaydah, and the bank remained without a local currency system. The government under the Imam’s rule still lacked institutions to run the state, its administration, laws, or justice. All power remained in the hands of the Imam and his deputies. Jeddou continued pushing for a new revolution before it was too late.

Jeddou made connections with external forces such as the Arab Nationalist Movement, the Free Movement in Egypt, and experts in the Soviet Union and China. He explained Yemen’s critical situation and asked for support. With time, the Free Officers’ activity amplified, and as their ties to Egypt strengthened, the Egyptians became a trusted ally in the fight against the unjust Imamite rule. By the time the big moment of change arrived, the Free Officers had garnered the support of many powerful and influential forces, all of which played a pivotal role in preparing for the great revolt.

Following the passing of Imam Ahmed on Sept. 19, 1962, his son Imam Badr took over as king and appointed Jeddou once again as commander of the Imam’s Private Guards. This not only worked in favor of the revolution, as Jeddou gained a means to monitor and study the palace, but it also placed him as the natural leader of it, and the Free Officers voted him as leader of the revolution.

Like a rope set on fire, news of the scheme spread rapidly to all other Free Officers stationed across the nation. The big moment was finally here. The moment my grandfather had been dreaming of for more than 20 years, when he would finally free North Yemen from the ruthless claws of the old regime, which for hundreds of years isolated the north and shed the blood of many of its people.

At 11 p.m. on Wednesday, Sept. 26, 1962, the uprising started. The first step was to take control of the radio station. After some altercation and firing of bullets, the Free Officers were able to seize the building. The next step was to take over Dar Al-Bashayer Palace. This battle, however, was more protracted, and fighting continued through the night. The situation reached a critical point when officials refused to obey an order from Jeddou, as commander of the Palace Guards, to unlock the doors to the artillery storage. Jeddou was faced with a precarious situation. Although risky and dangerous, he marched to the Imam’s Regiment at the palace, unprepared but optimistic he could resolve the standoff.

“Imam Badr has surrendered and ordered me to advise you to do the same,” Jeddou said. The soldiers were shocked and puzzled, “How could he surrender when just an hour ago he sent us word to keep fighting the disobedience of the sinners?” they asked. Jeddou, trying to stay confident and composed, responded quickly: “That message was probably sent before I was able to reach you. Do you not trust me? I am the colonel who taught and trained you to be the soldiers you are today. My advice for you is this: You are first and foremost from the army, and you answer to the army. What is happening right now is a revolution of the army. This is your revolution!” The soldiers then declared they were on Jeddou’s side.

Amid all this, Imam Badr disappeared into thin air. There was word he had escaped to Masour Mountain, so Free Army officials began bombarding his place of residence, causing him to flee the region. He attempted several times to enter Hajjah, but Jeddou had sent over Lieutenants to fortify the city and deny him entry. It is said that he eventually escaped to Saudi Arabia.

As the clock approached 5 p.m. on Thursday, Sept. 27, 1962, the revolutionaries had successfully eradicated the Imamite system and took control over Sanaa, including Al-Bashayer Palace. And over at Ta’izz, the brigadier and leader of the Ta’izz army announced their support for the uprising.

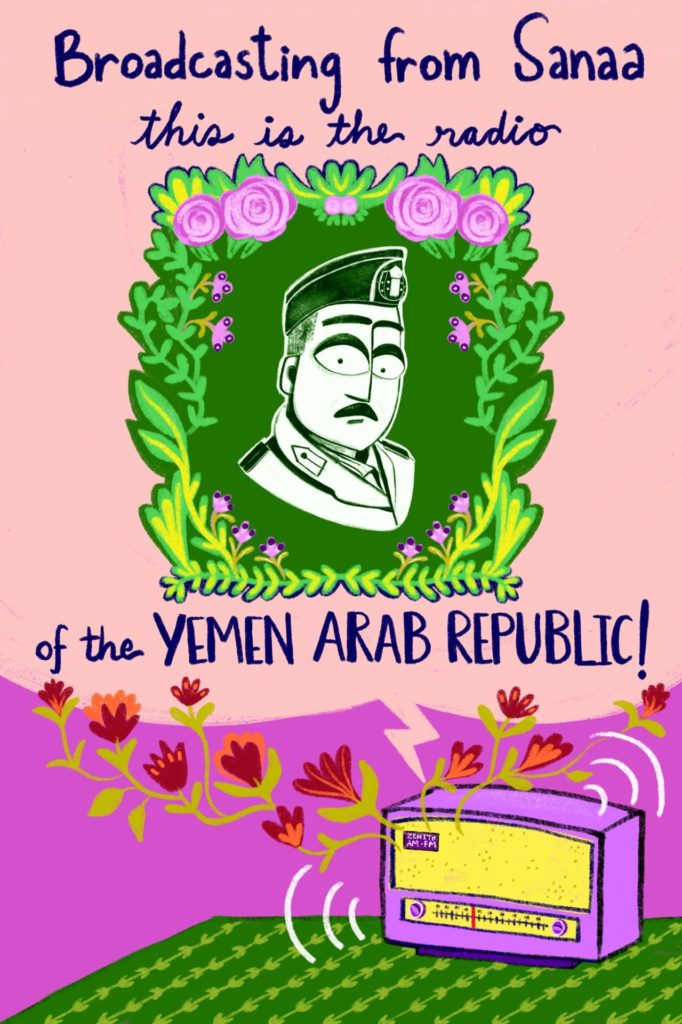

By Friday, Sept. 28, 1962, the new government of Yemen Arab Republic was formed under the leadership and presidency of Abdullah Al-Sallal. Upon the revolution’s glorious win, radio announcers began their program with, “Broadcasting from Sanaa, this is the radio of the Yemen Arab Republic!”

The September revolution altered the history of Yemen, changed the lives of its people, and it was led by my dear Jeddou, the fearless warrior, heroic leader, and steadfast visionary, who loved his country with every bit of his heart.

How I wish I was there to witness this hard-earned victory, to hug Jeddou and tell him: “You made it! You can now enjoy the fruit of your labor and build a bright, happy, and independent Yemen.” I wish I could tell him how much I miss him, that I lead by his honorable example every day and carry his name proudly with me wherever I go.

But for now, I take comfort in my memories of him and imagine we are both sitting in his beautiful sunflower garden in Sanaa, drinking shahi together, and he is telling me stories about the time when he was a heroic revolutionary and first president of North Yemen.