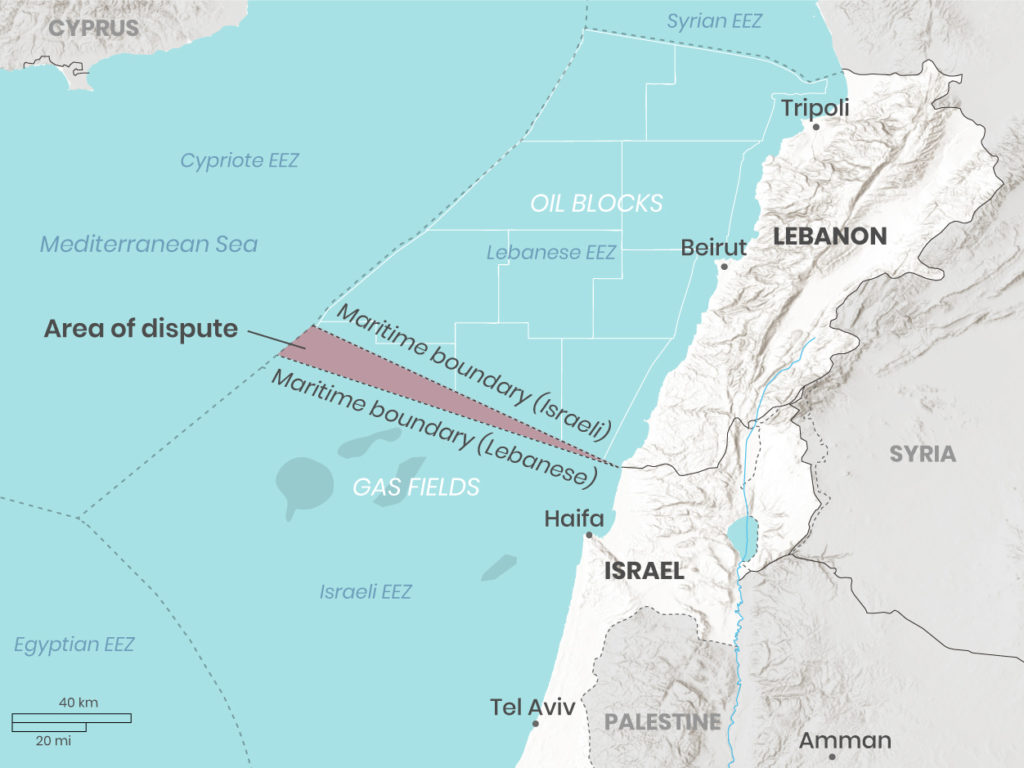

For nearly two years, from 2010 through most of 2012, I tried as a U.S. State Department official to mediate an agreement involving Lebanon and Israel – an understanding that would resolve a dangerous maritime dispute. Two neighboring countries, legally (and sometimes actually) at war since 1948, had drawn different lines out into the Mediterranean Sea laying contradictory claims to exclusive economic zones where each might pump hydrocarbons out from beneath the seabed. The result of these conflicting claims was 882 square kilometers (about 340 square miles) of disputed salt water.

When I took on this mediation task, I was already fully employed trying to mediate peace between Syria and Israel (the subject of a forthcoming book). While the Israel-Syria mediation was active, however, I also shuttled periodically between Lebanon and Israel trying to keep the peace in the wake of violent incidents along the 2000 Line of Israeli Withdrawal from Lebanon: the “Blue Line.” Israel-Lebanon combat would not, after all, facilitate Syria-Israel peace.

I was vaguely aware that geological surveys had indicated the possibility of hydrocarbons – mainly natural gas – in great quantities off the shores of Lebanon and Israel. Indeed, I knew Israel was already exploring and exploiting these resources. In Lebanon, however, political talk of treasure to be harvested had not translated into licensing for exploration.

Yet I was unaware of a brewing maritime crisis until I was contacted in late 2010 by Maura Connelly, the U.S. ambassador to Lebanon. She described the potential dangers quite vividly.

At the top of her list was the prospect of episodic Israel-Hezbollah violence on land acquiring a blue-water dimension. Second was the likelihood that international energy companies would shy away from investing time and energy on Lebanese hydrocarbons, and not just in disputed areas. Capital, after all, is a coward. Israel was already extracting natural gas well to the south of the area in dispute. Lebanon desperately needed hydrocarbon revenue, but the prospect of a confrontation with a militarily superior Israel was dictating caution among global energy firms.

Ambassador Connelly urged me to help the two sides reach a compromise: a single, agreed-upon line dividing their respective exclusive economic zones – a single line each would file separately with the United Nations, thereby avoiding the complication of asking two officially hostile parties to sign the same document. She cited published works of mine focusing on Israel-Lebanon boundary issues. I was, according to the ambassador, a natural for the task.

I pointed out in reply that the subjects of my books and articles – the 1923 Palestine-Lebanon International Boundary, the 1949 Lebanon-Israel Armistice Demarcation Line, the 2000 Blue Line, and disputes involving the “Seven Villages,” Ghajar, and the “Shebaa Farms” – were all land-based, and that my knowledge of maritime disputes was nonexistent. But Connelly was persistent, arguing that Lebanon-Israel violence in the Mediterranean would surely deep-six my Israel-Syria mediation. And she was adept at gathering support for her views from State Department higher-ups. Before I knew it, I was on the case.

Task number one, however, was to ascertain whether Lebanon and Israel wanted American help in resolving their dispute. That proved easier than I anticipated.

Connelly had done her homework with the government of Lebanon where I was, in any event, a known quantity to the president, the prime minister, speaker of parliament, and the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) – which had the lead in making and documenting Lebanon’s exclusive economic zone claim. Lebanon welcomed me as a mediator.

In Israel it was a bit more complicated, but not much. I was already well known to the prime minister and Israel Defense Forces. But I decided to rely on our very capable ambassador, Jim Cunningham, to run the traps. Israel came on board quickly.

Both sides agreed with me that the American effort would be low-key and as informal as possible. We would explore, as best we could, whether it might be possible for the two sides to accept the same line.

Task number two was to form a team and learn something about maritime disputes – how they arise and how they get settled. I got the complete package when I succeeded in recruiting, from the State Department’s Office of the Geographer, the leading U.S. expert on all manner of boundaries on land and at sea: Raymond Milefsky. Ray, regrettably, is no longer with us. But he was the person who brought this mediation to the brink of success. And if Lebanon and Israel are able now to complete the work they suspended in 2012, both sides will owe a great deal to the knowledge, creativity, and decency of the late Ray Milefsky.

Task number three was drawn from diplomatic best practices: establish relationships of trust and confidence with both sides. This meant making multiple trips and spending quality time in Jerusalem and Beirut. It meant listening carefully to the positions and rationales of the two sides and ensuring that each understood that the mediator was getting it. And the ability of the mediator to get it depended on active listening, both to the parties and to Ray, whose mastery of the cartography and international law governing maritime claims earned the respect and admiration of all.

This mediation still would have gone nowhere without Israel and Lebanon forming negotiating teams reflecting subject matter and methodological excellence. Both teams enjoyed superb leadership.

On the Lebanese side, the mediation began when Saad Hariri served as prime minister. Hariri designated his foreign policy adviser and the former ambassador to the United States, Mohamed Chatah, as my most senior governmental point of contact. Mohamed was cordial, but tough in insisting that Lebanon would stand up for its rights. A kindly and decent man, Mohamed shared with me his view that the Lebanese political establishment would seek to steal future hydrocarbon revenues, and he therefore favored the “Alaska approach,” whereby such income would be distributed directly to every Lebanese adult. No doubt it was that kind of thinking that got Mohamed assassinated in 2013.

When Hariri was replaced as prime minister in 2011 by Najib Mikati, my primary senior Lebanese counterpart would be Joseph Issa el-Khoury. Like me, Joe was not an expert in maritime disputes. But he became one quickly, and he had the complete confidence of the prime minister. He proved to be a superb interlocutor right through the end of the mediation.

The business of understanding Lebanon’s claim focused, however, on the LAF. A very capable officer – Maj. Gen. Abdul Rahman Shehaitly – led the effort. His top expert, Col. (later Rear Adm.) Joseph Sarkis, was one of the most professionally outstanding individuals I encountered during the mediation. During our many meetings at LAF headquarters my colleagues and I never ceased to be impressed by the professional excellence – scientific, legal, and diplomatic – of the Lebanese team.

The same impression prevailed on the Israeli side, where the team was led by a diplomatic all-star of long standing: Ambassador Oded Eran. Oded, who had served as Israel’s ambassador to Jordan and the European Union, was himself a relative newcomer to the magic world of maritime disputes. But he was able to rely on and channel the work of superb experts, people like Haim Srebro (Director General of the Survey of Israel), someone who spoke the same language as Ray. Oded also had at his disposal a first-class legal team in the ministry of foreign affairs.

With Lebanon’s political class promising that untold riches were right around the corner, Hezbollah, apparently, did not wish to be the proverbial skunk at the garden party.

Our effort would never get off the ground if Hezbollah – Iran’s Lebanese arm – had opposed it. At one point, however, the organization’s leader gave a speech saying that Lebanon’s government should exert all diplomatic and legal means to protect its exclusive economic zone rights. Not a word was uttered threatening violence. With Lebanon’s political class promising that untold riches were right around the corner, Hezbollah, apparently, did not wish to be the proverbial skunk at the garden party.

One of the first things I learned from Ray was that there is no one-size-fits-all formula for projecting lines out to sea to assert maritime separation boundaries. There are, to be sure, principles, procedures, and best practices widely viewed as appropriate in terms of cartography and international law. But there are also variables, often having to do with the validity and weight of land-based reference points on both sides of the boundary (in this case the Blue Line) employing equidistance to project a line. These variables, used by two parties making competing claims, can produce two lines sharply at variance, but each consistent with customary international practice.

Indeed, this is what Lebanon and Israel each produced: a line extending from where the two countries meet on the wave-washed rocks of Ras en Naqoura/Rosh Ha Nikra roughly 70 miles out to sea, meeting a perpendicular claim line already established by the Republic of Cyprus and accepted by both Israel and Lebanon. Lebanon did what it could, within acceptable customary standards, to make that line bend south, nearly touching established Israeli exploratory fields. Israel did what it could, short of violating anything appropriate, to make its line veer toward the north. Neither side did anything improper or illegal. But 882 square kilometers of Mediterranean Sea were left in dispute.

Much of 2011 was spent not only listening to Israelis and Lebanese explain why they drew their respective lines the way they did. My colleagues and I decided early in the process to take the time to explain Israeli thinking to Lebanese and Lebanese thinking to Israelis.

There were, after all, no direct talks between the parties. Everything went through the mediators, and each side was strongly inclined to think the other was simply out to steal as much as possible; that the other side had crudely drawn an arbitrary, unsupportable line aimed at maximizing gains at its expense.

By listening carefully, asking questions, and confirming the accuracy of what we were understanding, we accomplished two things: Each side knew its key points were registering with the mediating Americans; and the Americans, in turn, were able to explain these points to the other side, all but eliminating worst-case assumptions.

Ray was instrumental in convincing Israeli experts that their Lebanese counterparts were not ravenous thieves. He was able to convince Lebanese experts that Israel was not bent on stealing Lebanese natural resources. Using a slightly less technical approach, I was able to persuade Oded and Joe that the other side was behaving professionally and properly, even as maximum advantage was being sought.

To be sure, each side felt fully justified in demanding 100 percent of the area in dispute. Neither budged in the direction of concession and compromise. Lebanese and Israelis were hoping the American umpire would rule fully in their respective favor or, failing that, would make a one-sided proposal attractive enough to sell domestically.

I was not about to rule for one party or the other; this was not compulsory arbitration, and even if it had been, the excellence of presentations by both sides had convinced me this was not a simple case of right and wrong. On the contrary, they had both made sound cases. I was, however, at a loss as to what I should propose.

Both sides could rightly see a suggestion for a 50-50 split as an insult, given all the time spent in long meetings dealing with technical issues. And why would any arbitrary percentage allocation make any more sense than the senseless 50-50?

Briefly I toyed with the idea of avoiding a compromise line altogether by converting the entire disputed zone into a “unitized” entity whereby the parties would agree on a single energy company to extract hydrocarbons, market them, and send equal payments to each.

This, however, struck me as (a) a fancy version of 50-50, and (b) requiring a gratuitously complex agreement involving two parties not even on speaking terms. True, they would have to discuss “unitization” eventually in terms of sharing hydrocarbons located under or near an agreed maritime separation line. And I was hopeful those talks could be direct: perhaps under U.N. auspices in Geneva. Yet getting to the agreed line itself struck me as the direct and best way forward. But how? No one reading this account would be surprised to learn that the answer came from Ray.

At a team meeting back in Washington, Ray volunteered an idea. “You know, Fred, we Americans have lots of experience with peacefully resolving disputes of this nature, especially in the Caribbean. Normally – especially when the coastlines involved are relatively uncomplicated – we use a very simplified equidistance version of what the Israelis and Lebanese have done. And they have uncomplicated coastlines. So why don’t we do this? Why don’t we pretend we’re Lebanon and Israel’s Mexico; or we’re Israel and Lebanon’s Canada. Then, let’s strip away all the bells and whistles they included in their calculations. Let’s do this the way we typically do it to assert an American claim. I mean, what else can we offer these folks?”

Ray’s approach struck me as a brilliant alternative to spending years haggling with Israelis and Lebanese, meter by meter, over 882 square kilometers of sea. I asked Ray how it might come out in terms of a percentage split. “Fred, I don’t know. Give me permission to put my team to work on this and you’ll have the answer in a few days. We’ll use the most up-to-date software and I’ll check it a million times. But I can’t even guess where it would come out other than saying our line would almost certainly be somewhere in between theirs.”

Ray ran the calculations and drew a line. To avoid provoking a controversy over who owned what rock at the base of Ras an Naqoura/Rosh Ha Nikra cliff – an area never surveyed for boundary, armistice demarcation line, or Blue Line purposes – he started his line three miles offshore. And yes, it ran in-between the Lebanese and Israeli lines, which of course had swung south and north respectively. The Ray Line intersected the Cypriot line 60 percent of the way down from the Israel-Cyprus intersection to the Lebanon-Cyprus intersection, leaving slightly more than 55 percent of the disputed area on the Lebanese side of the ledger.

I must say that 55:45 – irrespective of who got what – struck me as more respectable, more attractive than 50:50. Yet any other split produced by the application of American methodology would have struck me as just fine; even 50:50. We had, it seemed to me, a respectable story to tell the parties. All that remained – or so I thought – was telling them and convincing them it was the best we could do.

Through our ambassadors I informed the parties that we were ready to offer a compromise proposal. We succeeded in persuading our London embassy to host us for separate meetings with the two delegations. The meetings took place on April 23 and 24, 2012.

I briefed the Lebanese team first. Joe and his team listened carefully, asked many questions (with Ray providing most of the answers), and seemed a bit crestfallen.

I had gone out of my way to praise the professionalism of the LAF team and to thank Joe and his colleagues for all the courtesies they had extended us. But I laid heavy emphasis on what I would also tell the Israelis: Applying the standard American methodology to resolve this dispute was the best we could do and the limit of what we could offer. We were not constructing a basis for further negotiation; we would not alter our recommendation without the mutual consent of both parties. Both sides would receive identical data packages detailing the methodology employed by American experts.

Joe and his colleagues expressed appreciation for the logic of what we had done, albeit tinged with regret that their position – 100 percent of it – was not upheld. Joe assured me he would brief the prime minister soon and he suggested I plan a near-term visit to Beirut.

The Israeli team was no more thrilled than its Lebanese counterpart with the American verdict. Again, Ray was grilled intensely by the experts. The Israelis had previously complained about land reference points selected by Lebanon for equidistance purposes. Ray was able to prove the validity of the Lebanese reference points, and he stressed one of the key aspects of the American approach to drawing a line: We had accepted Israel’s reference points in Israel and Lebanon’s in Lebanon. We had accorded each full weight in creating an equidistant line; something the Lebanese had not done with respect to Israel’s selection of an island off the coast of Haifa as a reference point.

Just as the Lebanese had done, the Israelis expressed grudging respect for the American approach. In the end, Oded pulled me aside. “Fred,” he whispered, “I’ll brief the leadership soon and will be as positive as I can. But you know, we’re not used to settling for 45 percent of anything.”

Israel was prepared to accept the compromise line subject to Lebanon’s acceptance. But Lebanon’s acceptance would be problematic.

Oded must have briefed Israel’s leaders well. In May 2012 Secretary of State Hillary Clinton received a letter from Israel’s foreign minister. Israel was prepared to accept the compromise line subject to Lebanon’s acceptance. But Lebanon’s acceptance would be problematic.

Prime Minister Mikati told me in Beirut in May that he wanted to say yes, but he would need cabinet unanimity. He asked that I brief several of his ministers. I did so without encountering negativity.

He also asked that I brief the opposition, headed by Hariri, the former prime minister. Again, there were no substantive objections beyond former prime minister Fouad Siniora insisting that the United Nations in southern Lebanon – not the United States – should be the mediator. I explained as best I could that the U.N. Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) had no role in maritime matters beyond the territorial sea 12-mile nautical limit, and that the secretary-general’s special representative in Lebanon was already making the rounds (at my behest) praising the proposed compromise. In the end, the opposition would maintain a discreet silence on the proposed compromise.

Prime Minister Mikati and Joe were delightful to deal with. But Mikati had many priorities competing with a maritime agreement for his attention, all of which boiled down to keeping his government afloat in the violent seas of day-to-day Lebanese politics.

His minister of energy and water, Gebran Bassil, had not yet been consulted by the prime minister on the proposed compromise. Mikati, fearing Bassil might blow things up, wanted to save him for last.

Bassil was making nationalistic speeches and statements conflating Lebanon’s exclusive economic zone claim line with a national boundary, one that could be amended only by parliament. In the end, I was obliged to tell the minister in Washington that Lebanon had no national boundaries with its neighbor to the south; that the maritime separation line proposed by the United States would, like the Blue Line, be provisional in nature until Lebanon and Israel negotiated boundaries and normalized relations. I would, however, have no objection if the minister wished to announce to the State Department press corps that he was unilaterally recognizing national boundaries with Israel on behalf of Lebanon.

Bassil got the point and might have supported the compromise had Mikati put it to a cabinet vote. But it never happened.

On Oct. 19, 2012 I was having lunch in New York City with Joe, telling him I planned to leave government – unless Lebanon were to approve the compromise proposal of the previous April – on Lebanese Independence Day: Nov. 22. Just as Joe was absorbing the news and promising to do his best, his phone rang. It was the prime minister’s office. The powerful head of Lebanon’s Internal Security Forces Information Office – Wissam al-Hassan – had been assassinated via car bomb. Thus began the rapid slide of the Mikati government toward collapse.

Weeks after leaving government (on time) and after joining the Atlantic Council, I received a telephone call from Lebanon’s excellent Ambassador to Washington Tony Chedid. He told me he needed to see me urgently. Could I come to lunch?

I reported immediately to his residence. Tony looked as if someone had died. I asked him if he was OK. “Fred, that is a question I should be asking you. I had no choice. I had to report to my government what happened to you. I am so sorry.”

I told the ambassador I had no idea what he was talking about. He looked puzzled. “I reported to Speaker Nabih Berri, who was very interested in your mediation and who always enjoyed meeting with you, that you were fired by the State Department and your proposed compromise line was withdrawn by your government.”

I hoped against hope he might be joking. But it was not April 1. He was clearly distressed, and his puzzlement only increased as I insisted that the tale being told was news to me and contained not a word of truth. “But Fred, I was told this in confidence by a senior State Department official!” When he declined to identify the official, I suggested he check with Secretary Clinton or her deputy, Bill Burns. As I left, I told the ambassador I could not verify the current status of the proposed maritime separation line; I had been a private citizen for several weeks. But I assured him I had left the State Department voluntarily and, to the best of my knowledge, on good terms with all.

On returning to my office I called Ambassador Connelly in Beirut. Coincidentally, she had just heard from an outraged speaker of parliament. She knew the story of my sacking was untrue, but could I please come to Beirut and calm Speaker Berri? Within a week or two I was in Berri’s office, assuring him I’d not been fired. Connelly told him the U.S. compromise was still on the table. Berri did a good deal of handwringing about “American friends of Lebanon” always being ousted from positions of power of influence but, in the end, I suspect he believed me, and the United States’ honor was upheld.

Years later I was told that the State Department official who had eventually replaced me on Lebanon-Israel maritime matters – someone not assigned to the Near East Bureau – had spread the story in question.

Years later I was told that the State Department official who had eventually replaced me on Lebanon-Israel maritime matters – someone not assigned to the Near East Bureau – had spread the story in question. He believed he had an alternative that both sides could accept: pursuing a unitization agreement covering the entire disputed area without drawing a line. As it happened, neither side was interested. The unitized zone approach was something I had considered and discarded. The idea nevertheless had merit; the diplomatic tradecraft employed to kill an American proposal welcomed by the leaders of both countries had none.

In recent weeks, Washington has succeeded in reviving its Lebanon-Israel maritime mediation. The “Hof Line” – something that ought to be called the “Ray Line” – has received some attention in the press. After three sessions there is no breakthrough. But at least the two parties are in the same room in UNIFIL headquarters, something Israel declined to do a decade ago.

The U.S. maritime mediation of 2010-2012 is missing from the annals of great diplomatic accomplishments. Indeed, in the end, it failed. But the parties to this ongoing dispute would be ill-advised to ignore what they accomplished, with good-faith American help, nearly a decade ago. They can, perhaps, try marginally to improve on their predecessors, bearing in mind nothing happens without mutual agreement. Ray gave them everything they need now to get to “Yes.” By honoring his memory, a win-win scenario – the rarest of occurrences in the Middle East – can come about.