While authoritarian regimes are powerful and violent, they’re also idiotic. Authoritarians don’t employ wit and rationale to rule or set laws, leaving it all primarily to force. Even if they were intelligent when they seized power, they eventually become so calcified in their reign that intelligence is surplus to need. One doesn’t have to be a genius to crack open the skull of a tied-up wiseass.

These regimes don’t have a sense of humor, not only because they don’t want to have one, but also because they don’t need to have one. People have a sense of humor to show they are smart, tolerant and approachable, all qualities authoritarian regimes hate. In their day-to-day lives, most despots aren’t really familiar with a sense of humor; they take themselves too seriously, and they want people to take them just as seriously. The more of a joke they are, the more seriously they want to be taken.

This humorlessness begins from the moment an authoritarian takes power. They want to instill fear in the populace to make sure people don’t consider going against them. When the revolution happened, the Egyptian people had been living in a state of listless fear; the previous generation had tasted the fear themselves and passed it on, second hand, to that generation. This generation is headed toward this lethargic fear again, as anyone who speaks out suffers formidable consequences. But, just as with the Boggart in Harry Potter, the way to defeat the fear that despots sow is to laugh at them, stripping them of the most powerful grasp they have over people.

The year we launched the humor website AlHudood, 2013, was the year we lost hope for change in Jordan, but it was a good year in terms of hope for the media. A few media outlets sprung up. There weren’t any new freedoms granted, but people were triggered, and even if briefly, a feeling of empowerment was palpable.

That year, my co-founders and I gave up on a new 30-person political party, which had managed to suffer two major schisms within the first two years since 2011. We were working as screenwriters, or more accurately we were unemployed. Any writing job we were able to secure in the tiny writing market was butchered to the point where any association with the work made me feel a deep shame, internally and in front of my friends who knew I edited the script to suit the client. We were writing comedy, asked to do something unique, edgy and funny, and however little or much of that was delivered, the client would ask us to strip it down slowly so as not to offend society, not to upset the government, not to make a friend of the producer uncomfortable, until nothing was left.

Being a long-time follower of the satirical American publication The Onion, I had long been interested in this type of writing, but inspiration to start the magazine came about quite suddenly. It happened one day as I was driving back from the airport. I was looking at the aftermath of a multicar accident with people cramming up before it to get their own share of excitement and blood when an Onion-esque headline came to me: “Young entrepreneur sets up box office before accident site.” I wish it were a better headline that led to the inception of the publication that is now an inseparable part of my life, but its macabre feel still lingers in a lot of work we do today. One prime example satirizes the extent and myriad ways that destruction was wrought on Syria: “Syrian man succeeds in dying of natural causes.”

We met that evening and discussed the project. With our combination of creative writing, comedy and activism, we felt like we had the perfect skillset to start the publication. We came up with three potential names for it, chose one before the end of the evening and bought the domain name. I built the site in a few weeks; we wrote the initial 15 articles for launch over a few more weeks and then went live. Although those articles weren’t our best work, the day we launched, we received 20,000 readers. The format got people excited — or very confused and angry — and the articles messed with a few of the political and social lines to pique people’s interest and, to a lesser extent at that point, that of the authorities.

There was a rush of excitement. We felt we’d made it, and all we needed to do was grow. We just needed to find some writers, then develop the site and get some ads, and we would be sorted. But none of that happened (spoiler alert: it still hasn’t). The skills needed for political satire writers are quite particular, and no number of ads or calls for contributions or contact calls led us to them. They needed to be able to write humor (that was actually funny), to understand politics (young people are highly deterred from politics from a young age), to know Arabic well (the better educated in Jordan are much better at English than they are in Arabic) and to be risk-takers willing to work for a non grata organization.

Approaching the advertisers and investors with our political content wasn’t easy either. Initially, we were laughed out of advertising agencies the moment we loaded the site on their projectors, with headlines like “Jordan to reinstate capital punishment after rising popularity in the region” or “Police shoot man to save him from committing suicide.”

Even when we gained traction, we still got rejected, but after a much longer and more laborious process. The junior creative would pitch to the account manager, and they would love it. We would then go back and forth, propose how we could advertise for them and create native content just for them, how they would be the edgiest and the best, to which they would agree, and none of us could hold back our excitement. And as we came close to signing and it reached the decision-maker, they would abruptly pull the plug. Investors on the other hand were kinder: They rejected us outright.

After nearly a year from launch, the initial excitement faltered. I was 28 with a grand total of zero in my bank account, and I was moving to the U.K. to live with my then-fiancée. AlHudood either would be a pet project we did in our free time as we waited for it to die, or it needed to generate some income. We approached every donor known to Google. Our chances were slim, but we submitted anyway, almost certain we wouldn’t get the money — because who in their right mind would give money to an organization that wasn’t even able to get registered, in which no one else has put any money or given validation, with founders who have no track record? Moreover, who would fund an organization that is doing political satire (actually doing satire at all in the region) in a country that doesn’t welcome it, where the media is weak and highly polarized, and where there are higher priorities to fund. One funder we were less pessimistic about was the European Endowment for Democracy, which claimed to fund the unfundable. We turned out to be just the right amount of unfundable for them to give us our seed money (which we satirized in an article the same day we signed).

Years on, we are now a global team of 15 that includes editors and journalists, writers and designers, and a sizable technical development team that backs the editorial team in taking their jokes on the media to the extreme. The team members I work with are incredibly intelligent with an eclectic set of diverse skills, and while they have a great sense of humor, funny isn’t the first word I’d use to describe any of them. But we do know what makes a powerful, witty joke and how to build it, and, since our format is written, regardless of how much wit any of us actually has, we have the time to produce a witty article.

However, getting to this point took practice. When we started the magazine, we just sat looking at the news all day, waiting for inspiration to strike. It wasn’t efficient and it wasn’t funny. Our early days of chatting and smoking all day are gone, and we now have a set of systems to wring satire out of our brains.

Today, we run different types of meetings regularly, each to produce a different type of content.

Our editorial meeting is an hour long, every day. But unlike traditional editorial meetings, it is not about pitching, but rather ideation and co-creation; and instead of everyone talking over each other, it is all done in threaded chats. We collect news we believe we should comment on, decide which stories are most important, and then delve into long discussions about what happened and why and what it means, and who is the asshole in the story to take aim at. As we near a consensus about our angle, the team shoots down headline after headline as we attempt to phrase the sharpest and funniest one. That debate becomes the main material that the writer uses for arguments and jokes.

This hourlong meeting leaves everyone depleted, requiring a good half hour to recover from the sparring. The biweekly Headlines Hour is more fun. During this meeting, writers and editors, designers and developers, and even our accountant leave their work for an hour of headline ideation. There is one rule for this meeting: By choosing to take part, they must contribute a headline at least every five minutes. In the first 15 minutes, the headlines are the type that make dad jokes feel like “The Daily Show,” but once we get into a rhythm, it becomes difficult to get the team to stop at the end of the hour.

What makes the setup of AlHudood difficult to replicate, however, aren’t the processes. Over the course of the last seven years, we have had a lot of discussions and debates that, in the early days, were chaotic and infuriating. How do you tell someone their headline just isn’t funny? Can they not just see that it isn’t? It turns out that telling someone that their jokes aren’t funny won’t suddenly inspire a side-splitting headline out of them or any positive feelings toward you. Over the years, we have developed a way to communicate with one another about what makes something funny and how it can be made better. We are able to build on ideas through these conversations. And the spirit guiding the team is that if you see a headline that doesn’t work, instead of explaining how it doesn’t, just rewrite it in a way that it does.

Last year I was talking to a good friend about AlHudood, and he told me he has it on good authority that Qatar funds the site. It wasn’t even an accusation from him. He was sympathetically saying it like “money has to come from somewhere.” I opened the banking app on my phone and, unfortunately, no money had come from Qatar that day either. Articles like “Growing fears that migrant workers will all die of heat before being able to finish installing air conditioners at World Cup stadiums” must have helped.

While a few independent outlets exist, there are hundreds of media organizations in the Middle East that are either government- or politically funded. The common understanding for the average person in the region is that the media is there to push a certain agenda and tarnish the reputation of the other: The better you do that, the more successful and better you are at your journalism.

Plain impartiality in this environment becomes even less meaningful and less powerful, and gets lost among all the other voices as boring, weak and unsexy. All of which is in some way true. Impartiality doesn’t provoke emotion, but this is critical to get people engaged. In 2011, the sense of defeat that had built up over the decades was converted to anger, and then the anger mostly crumbled back to passive resentment and bitterness. So at AlHudood, instead of taking no sides, we attack all sides.

When we write on the war in Yemen, we hit at the Saudi regime, the al-Houthis rebels, Iran, the United Arab Emirates, the U.S. and continued European weapons sales. One particular headline that is dear to my heart encapsulates this spirit: “Saudi Arabia condemns Houthis’ use of human shields even though it plans to bomb them anyway.”

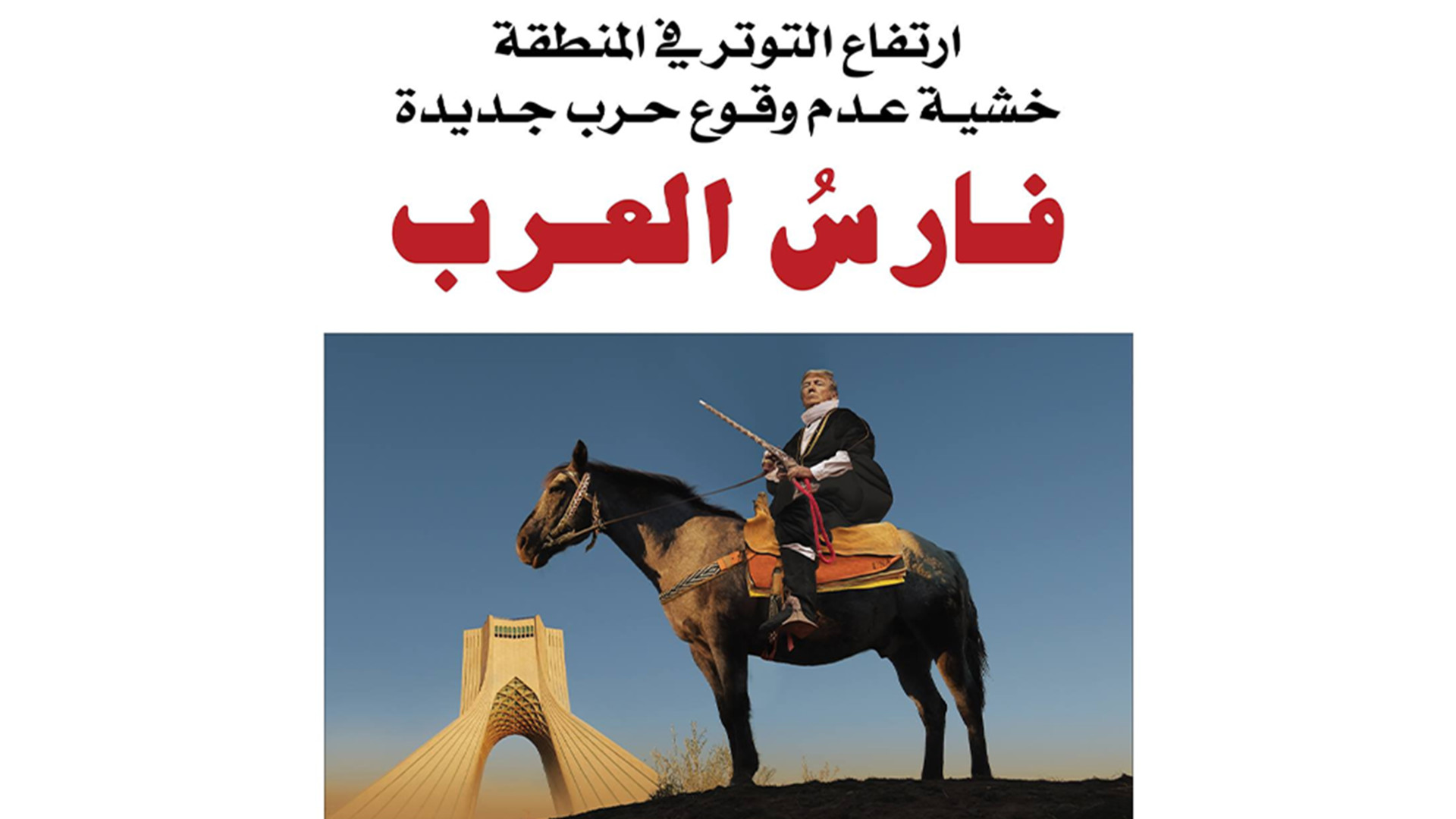

This isn’t to say that we are able to hit all sides equally. Saudi Arabia, Israel, Syria, Iran and Egypt, to name a few, not only disregard, on a regular basis, every ethic and value we respect and stand for, but they do it so brazenly and openly that it forces us to cover them constantly (as was true of the media during former President Donald Trump’s time in office). What we make sure of, though, is that every article denouncing one side will have to include some blows to the other, even in the headline, where possible. When we give unfair coverage, we attempt to keep the other side in our mind and dig that much deeper to give them the coverage they also rightfully deserve. We do this with most of our coverage, but in some places like Egypt, the opposition has been so thoroughly crushed that it’s not really possible.

This approach left a lot of readers confused, especially in our early years. They share a headline mocking Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and they praise and comment and concur. Then they find us criticizing Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan the next day, and their insults come raining down on us. They love us for sating their own anger at injustice, then hate us for smashing their idols, leaving them perplexed. They can’t figure out why would we bother slagging off one side if we are going to undo all that good work the next day by criticizing the other side?

We take satire seriously, probably a lot more seriously than most “real” news organizations or media in the region covering the news. We do this to compensate for the fact that satire is all we do. (A few years ago, I was answering my cousin when she asked what I was doing these days. Her response was, “Oh, I know you do that. But what do you do with all the other time?”) But taking the work so seriously also has an interesting, unintended side effect: It makes serious news organizations look even worse than they already do, from their basic grammatical errors to hate speech to republishing articles unknowingly copied and pasted from satire.

So four years ago, while joking about how the media is so awful that they deserve awards for the extremes they go to with their work, we realized this is just what they needed. That year the AlHudood Award for (Worst) Arab Journalism (AAAJ) was born to celebrate and highlight the worst excesses of the media, to name and shame those journalists and organizations that are being read by hundreds of millions of people every day and whose offering is far from journalism.

And unlike most media monitoring and media literacy initiatives, which distinguish what is true from what is false, we believe that misinformation and disinformation in a region with massive, elaborate media organizations that are decades old are a lot more sophisticated, and the award accounts for that. While there is a category for “blatant lies,” others include sycophantism, hate speech, propaganda and worthlessness (covering inconsequential pointless news about despotic rulers). We also publish a weekly piece that corrects commentary columns with the most inaccuracies, and it is developed to look and feel just like elementary school teachers’ marks on their students’ papers. While this might give the impression that we are a bunch of arrogant writers and editors, in fact it’s mostly that the bar is so low.

Starting the publication was not a direct act of defiance. The point of this project when we started wasn’t to expose and critique and debunk. It stemmed from an innate need to freely express our thoughts and opinions using tools and skills we happen to already have. While we understood that it might put us in trouble, we didn’t look at ourselves as acting against the law. We are antagonizing a lot of ferocious regimes with our writing, but the whole team views this as something we have the right to do. It doesn’t even feel like we are rebelling, because we find it impossible to look at a naked emperor and cheer along with the rest.

And even though on a day-to-day basis we feel like we are just going about our work like other people, we take incredible pride in it. Not enough people are doing this basic act, partly because of a lack of tools and also the inability to see, longer term, where any act of defiance might lead given that everything is crushed so quickly. In addition, the foundation of political thought is weak.

Of course, this type of work puts everyone involved at a certain level of risk. Almost everyone works anonymously, and everyone feels a certain air of discomfort at all times. I can’t (probably ever) go home, and everyone is, to one degree or another, overworked as we try to cover a wide geopolitical area with a small team and little funding. We do all of this knowing that satire can do things, but we are also aware of all the things that it can’t do.

Satire won’t change anyone’s mind, but it might get someone sitting on the fence to consider another perspective. Satire won’t topple thrones, but it will unsettle their occupants. It won’t change rules on freedom of speech (except maybe in the wrong direction), but it will remind people what freedom of speech looks like and inspire them to claim it and fight for it. (Before 2011, no one spoke ill of the king, not even at home when surrounded by their own family. “Just in case,” we used to say.) Satire won’t make people revolt, but it might fuel their anger. It “mostly” won’t uncover hidden issues and do the work of journalism, but done correctly, it can amplify its work and reach people it would have never been able to reach.