It seemed like I was the only one driving down Fourth Street, headed into the downtown area of Oklahoma City. The road led me to a vacant lot where the ruins of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building once stood. There was nothing to see, just a ruin of concrete, gravel, and dirt encompassed by a chain-link fence stretching around the entire block. At first, I thought it was a construction site. The remains of the building had already been demolished a week earlier and, to my surprise, all the rubble and debris had been cleaned up. It might have always been this way — vacant and soulless. Except everyone knew what happened on April 19, 1995.

As I exited my Honda Accord, crammed floor to ceiling with my college belongings, a slight breeze was kicking up dirt and pushing dead grass and trash across the weathered asphalt street. A large, warehouse-like building directly across from me was boarded up. I walked the sidewalk alone looking at the makeshift memorial to the victims: the 168 killed and 800 wounded by a 4,800-pound bomb hidden in a rental truck. The flowers, teddy bears, and handwritten notes were still tied to the fence, while candlelit vigils long since extinguished lay burnt on the sidewalk.

As I walked the grounds, I reflected on a few fateful moments in my young adulthood that seemed directly tied with my desire to travel on my own to the site of this deadly, American terrorist attack.

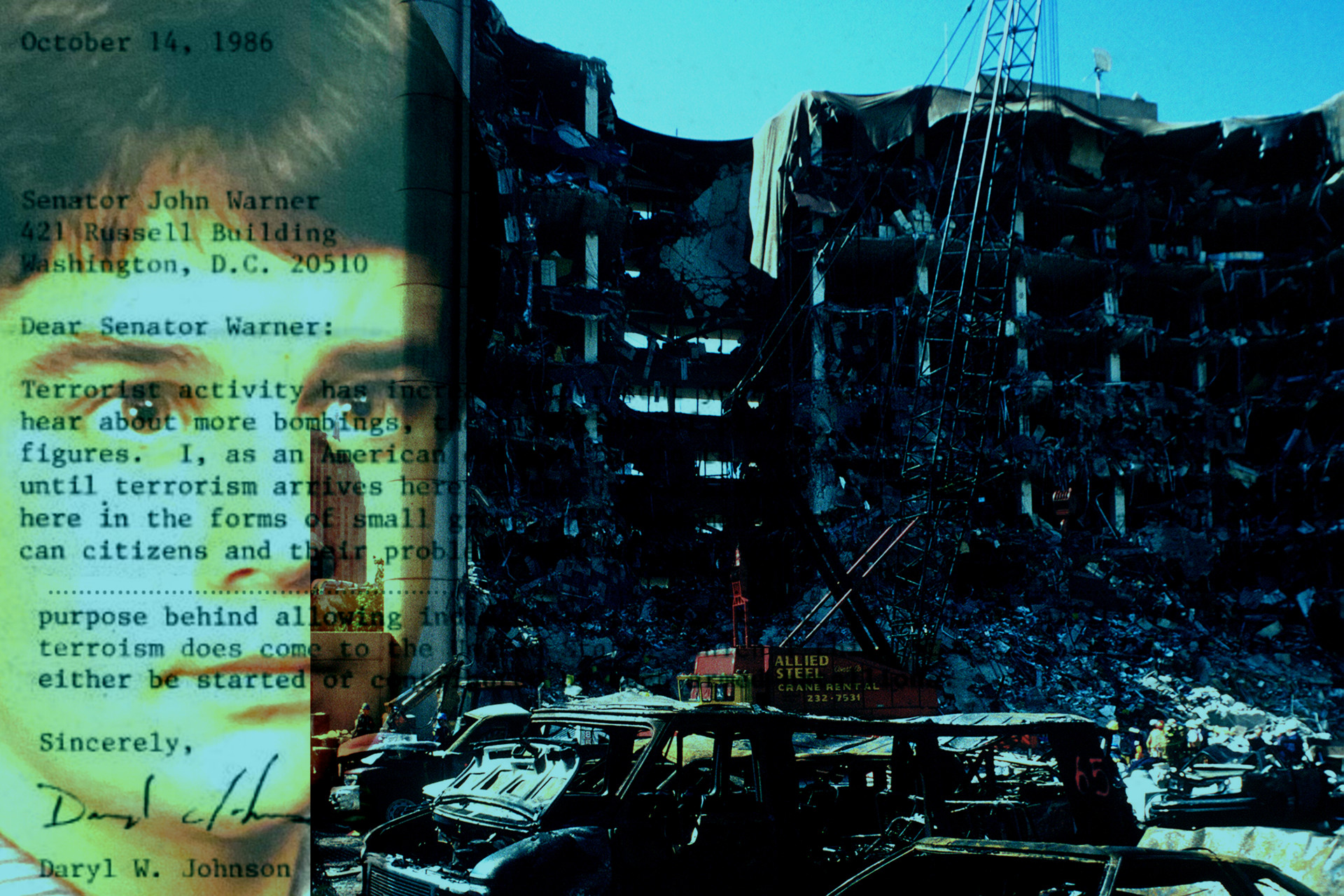

As a 17-year-old boy scout working on his Eagle rank merit badge requirements, I had to write a letter to an elected official discussing a relevant issue in my community. In October 1986, I wrote to then Sen. John Warner (R-Virginia) to warn him about the threat of domestic terrorism. I was influenced by recent events: the 1985 standoff between the FBI and an insular community of white supremacists called “The Covenant, The Sword, The Arm of the Lord”; the violent criminal activities of The Order, another white supremacist group operating in the Pacific Northwest; and the cult of Lyndon LaRouche, an extremist political figure who lived on a fortified compound in Loudon County, Virginia, near where I lived in Warrenton.

“Terrorist activity has increased in recent years,” I wrote to Warner. “With each passing week, we hear about more bombings, the hijackings of planes, the kidnappings of political figures. I, as an American citizen, begin to wonder how much longer will it take for terrorism to arrive here in the United States.”

At 19, I served as a missionary for the Mormon Church in southeastern Michigan, proselytizing in suburban and rural areas. The harsh winter climate, large swaths of wilderness, Great Lakes, industrial landscape, and cloistered demographics make Michigan inviting to survivalists, white supremacists, Black nationalists, and other extremists, a few of whom became interested in the Mormon faith. There was the homeowner who displayed an upside-down American flag and who wouldn’t shake my left hand because he believed it was “a communist handshake.” Another potential convert had a large painting of Hitler hung on the wall in her home. In time, I found the Book of Mormon had to compete with flyers from the Ku Klux Klan in the Detroit suburbs of Madison Heights, Warren, and Clawson.

So as I stood in downtown Oklahoma City, I couldn’t help but think of the Michigan background I shared with two of the perpetrators of this atrocity: Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols. They were both enlisted men who were transitioning out of service — they were U.S. Army veterans who had served in the same unit during the Gulf War. Once committed to defending U.S. national security interests through their military service, they became enemies of the state, hellbent on undermining American society through an ideologically motivated act of mass violence. I’d run into guys like these before, individuals who shared their outlook, and had tried to reach them spiritually.

A few days after visiting the attack site, I arrived home in rural Virginia. My new job was as an Intelligence Research Specialist at the Army Counterintelligence Center (ACIC) at Fort Meade, Maryland, where I’d monitor threats to the U.S. military coming from within the continental United States, a program called CONUS force protection.

At the time, CONUS force protection was focused on a bygone era of far-left violence against the military in the 1970s and early 1980s by communist sympathizers and Puerto Rican nationalist groups like the FALN and Macheteros. There hadn’t been an attack by these groups on military personnel or facilities in the U.S. for over a decade. Many left-wing terrorist members were incarcerated, while a few remained fugitives, forgotten phantoms from an outdated, radical era.

And yet, the data told a different story. At the ACIC, I noticed that much of the law enforcement and open-source reporting involving threats to the military at home were linked to right-wing extremists, specifically militia members and white supremacists. Extremists had been arrested for stealing military weapons and equipment as well as plotting to attack the military, motivated by various conspiracy theories related to black government helicopters, the New World Order, and citizen detention camps, among other bogus claims. I raised the issue through my chain of command, which allowed me to begin careful, limited monitoring of these groups to assess the threat they posed to the Army. At the time, some questioned why I even bothered. By 1998, the emerging new threat to U.S. national security was Islamist extremism overseas, embodied by al Qaeda, which had begun bombing our embassies in Africa.

Yet the threat of homegrown, non-Islamist extremism persisted, as I discovered in 1999 when I joined the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. White supremacists, militia extremists, and others still violated federal firearms, arson, and explosives laws. There were intelligence threat concerns related to right-wing extremists plotting violence as the millennium approached, combined with the usual paranoid fears of Y2K and the cult hysteria about the year 2000 ushering in the end of the world. In fact, there were a couple of high-profile, ongoing criminal investigations related to militia extremists plotting attacks on critical infrastructure in California and Florida.

In 2000, I traveled to Cheyenne, Wyoming, to assist agents as they arrested two neo-Nazis for manufacturing dozens of improvised explosive devices and illegal firearms. Two years later, I helped with an investigation into a Ku Klux Klan faction in Benson, North Carolina, responsible for the murder of a fellow KKK member who they suspected of being an informant. The same faction was also being investigated for plotting to bomb a county courthouse and assassinate the local sheriff.

If monitoring domestic terrorism wasn’t a high priority before 9/11, after that event it became almost a coy relic of a distant past.

If monitoring domestic terrorism wasn’t a high priority before 9/11, after that event it became almost a coy relic of a distant past. Nevertheless, I continued to work for the U.S. government in the same capacity, joining an agency created expressly because of al Qaeda’s gruesome attack on U.S. soil. In 2004, I joined the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Intelligence and Analysis as its only domestic terrorism analyst. Even flying solo, I found, there was plenty of work to do supporting projects related to critical infrastructure threats, developing talking points for DHS leadership, and writing strategic intelligence and policy reports. By year two, I finally had four contract analysts working alongside me, with plans in place to hire three more. I wanted this program to grow, but I also realized that I needed to be extremely judicious about the type of analysts that were hired due to the highly charged social and political issues encompassing domestic terrorism. Debates about gun rights, abortion, immigration, and taxation permeated the various far-right extremist movements. But they were also mainstays of the American conservative movement. Monitoring these issues within the right context, and with U.S. taxpayer money, was essential.

I was also caught in something halfway between boondoggle and PR exercise. My higher-ups at DHS viewed the work my team did as a tertiary responsibility and a potential political liability. Nevertheless, they also thought it gave DHS convenient political cover against any allegation of racial profiling of Muslims in the heightened post-9/11 security climate. Perhaps for that reason alone, I got what I asked for. When the contractors left, I was able to hire five staff analysts, some of whom had extensive backgrounds in monitoring and assessing domestic extremism gained from their work in civil rights organizations, other DHS agencies, as well as intelligence fusion centers. Even if this was the department’s nod to professional tokenism, it kept us vigilant against threats having nothing whatsoever to do with al Qaeda.

Less than a year after assembling this analytical team, I authored the 2009 DHS report on right-wing extremism meant for law enforcement only. It was subsequently leaked to the press and a political backlash ensued, the aftermath of which scuttled my unit’s work at DHS.

The Republican Party and conservative media were offended by the term “right-wing extremist” (a legitimate term used in the counterterrorism community and academia) and objected to a vague definition of it that they intentionally misconstrued, claiming it was an attack on conservatism, the GOP, and the newly formed Tea Party, a grassroots populist movement that coalesced in opposition to Barack Obama’s presidency and what it saw as the administration’s radical leftist agenda.

The American Legion, too, was angry that my findings raised the prospect of returning veterans becoming targets of recruitment by right-wing extremists. No one on the right wanted to hear that the U.S. threat environment was shifting from homegrown Muslim extremists aligned with al Qaeda to violent, right-wing extremists. As is customary with inconvenient intelligence, my work was politicized, and my team was dissolved.

Within a few weeks of the release of the 2009 DHS report, the first in a series of violent, right-wing terrorist attacks occurred. First, there was the killing of three police officers in Pittsburgh by a white supremacist, then the murder of an abortion doctor in Kansas. These attacks were soon followed by the fatal shootings of two sheriff’s deputies in Florida by a militia sympathizer and the fatal shooting of a guard at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. The new wave of domestic terrorism I had predicted was upon us.

Now, more than a decade on, America has witnessed the unprecedented growth of right-wing extremism and the increase in its butcher’s bill: the shootings at the Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, in 2012 (six deaths); the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, in 2015 (nine deaths); the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh in 2018 (11 deaths); a Walmart in El Paso, Texas, in 2019 (23 deaths). The body count grows seemingly with each attack, year after year.

Even more demoralizing than the atrocities is how elected officials have dismissed, apologized, or even showed support for the perpetrators. The former president of the United States, Donald Trump, referred to white supremacists who attended the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, as “very fine people”; asked the violent, far-right group Proud Boys to “stand back and stand by” during the 2020 presidential debate; and messaged militia members to liberate the states of Michigan, Virginia, and Minnesota during anti-lockdown protests in 2020,among other irresponsible statements and shows of support. Other GOP representatives have delivered speeches to and had their photos taken with known extremists, opened the door for a mob to breach security at the Oregon State Capitol last year, and failed to call far-right violence “terrorism.”

Furthermore, the internet and social media have become force multipliers for extremist recruitment and radicalization. Such technologies have allowed otherwise disparate extremist movements to organize, communicate, network, message, and plot with ease, privacy, and stealth. Dangerous conspiracy theories, like QAnon, are also able to spread through social media with incredible speed, influencing large swaths of people to believe falsehoods and mobilize out of fear and paranoia.

The culmination of this grim trend was a violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, fomented by none other than the president of the United States.

As I reflect over a half-century of my life, a majority of which I’ve spent studying, analyzing, and understanding the threat of right-wing extremism, I now realize my life mission has been uniquely shaped and guided to combat it. From the religion I was born into; to my interest in an Arkansas white supremacist standoff; my Mormon missionary service; a personal pilgrimage to the site of the Oklahoma City bombing; and later, my work at the ACIC, ATF, and DHS, each of these experiences informed my knowledge about domestic terrorism. Despite using that expertise to warn law enforcement and policy makers in 2009, there is no satisfaction or vindication with each domestic terrorist attack. And since that warning in 2009, the right-wing extremist threat has only grown far worse year after year, plot after plot, attack after attack. It has metastasized into a global terrorist threat with the attacks in Norway (2011), Canada (2017), and New Zealand (2019), among others. Now, the Capitol insurrection on Jan. 6 has brought this threat to the doorstep of our legislators, the very people who have ignored it for too long. My only hope is that our leaders in government, publicly elected officials, law enforcement, and the U.S. intelligence community belatedly recognize this threat, assess its national security implications, and finally do something about it.