In the summer of 1978, an American artist named Steve embarked on his first journey through Europe. Traveling alone and carrying little more than the essentials, he had sold his most valuable possession, a pickup truck, to pay for the airfare. On a bright June morning, Steve, my father, landed in Vienna with a simple plan: make it to Greece by the end of the summer to reunite with family. He bought a purple bicycle, a pair of panniers and a few maps, and began pedaling south.

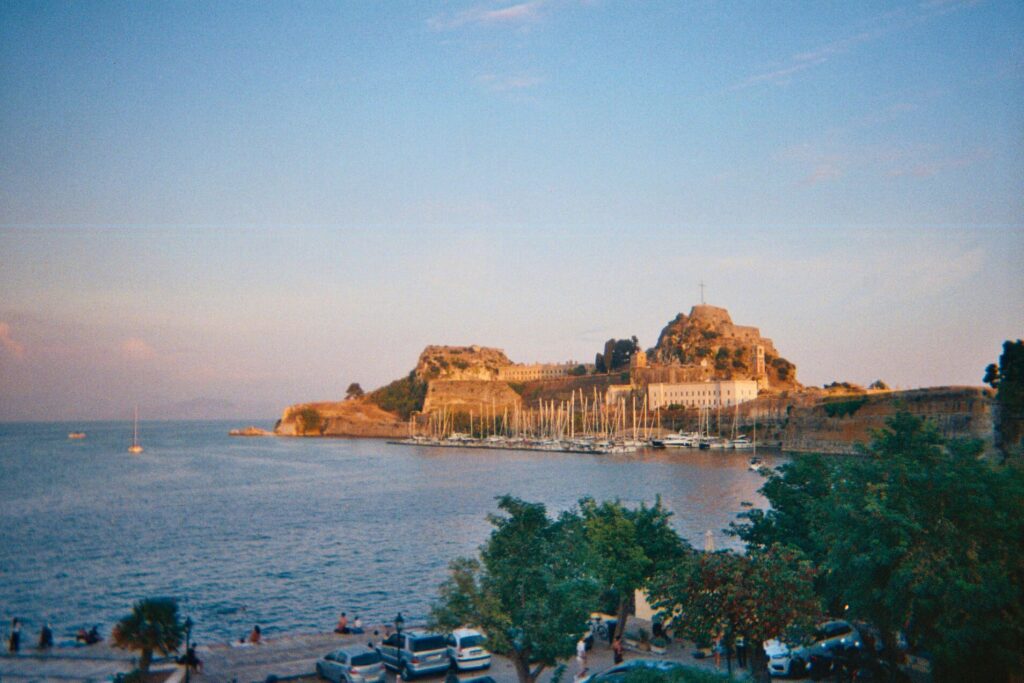

What followed was the adventure of a lifetime. Over the coming months, my father cycled first through Hungary and into what was then Yugoslavia, through bucolic fields alongside peasants toiling with scythes and oxcarts, then down the coast, free from mass tourism. He took a ferry from the Croatian city of Dubrovnik to Corfu in Greece. Island-hopping his way to Crete, he slept on rooftops when he wasn’t cycling, and ate plenty of his favorite fruit, watermelon.

Forty-seven years later, I set out to recreate his journey, an homage to my father and an exploration of the Europe he left behind. It was a region that I, too, despite living in Paris as both an American and a French citizen, had never traveled to. I cycled in his tire tracks to see if I could do it, physically and emotionally, but also if such a journey was possible today. In a world of fluid borders, interconnectedness and globalization, can you leave the world you know and stumble into a new one? What remained, I wondered, of Steve’s mysterious, poetic Europe?

In early July, I took a train from Paris to Vienna, schlepping a hand-me-down Cannondale touring bike. From there, it would take me seven weeks to travel 1,200 miles. As I made my way from Austria to Greece, I was confronted with the ways in which Europe had changed in the nearly half-century since my dad embarked on the same path. His journey, some 600 miles, covered roughly half that distance. By night train and then ferry, he skipped past the mountains of Bosnia, quite possibly too rugged for his simple touring bike, and then skirted around isolated Albania, shut off from the world under a particularly oppressive communist regime.

Steve traveled through a Cold War Europe where alliances were clear-cut, borders were firm and national identities rooted in deep, if painful, histories. To my father, each new place on his trip felt like a different world with strange new languages, products he didn’t recognize and political histories written across many centuries. His Europe was a quilt: a patchwork of nations knitted together, yet clearly distinct from one another.

I found a continent grappling with globalization, uniform commercialism and rising nationalism. Everywhere I looked, there was a flattening sameness, including in the politicians who wielded nostalgia like a weapon, sowing division. More than once, I found myself longing for the Europe my father had encountered, which I imagined as a fairy tale of family-owned inns, dapper old men in felt hats and cafes filled with smoke and chatter.

I was increasingly convinced it no longer existed. But I also feared what might be stirred to life if demagogues and populists sought to resurrect the imagined glory of their past and its restless ghosts.

I had built up an image of Vienna in my head: of literary salons, hot chocolate and plush armchairs that I imagined had once been sat in by the novelist Stefan Zweig, and of my dad, waltzing into a bike store and selecting his purple bike.

He arrived there on an expiring Interrail train pass, having visited the fairy-tale Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, whose arches and turrets inspired the Disney logo. He nearly passed out from altitude sickness in the Austrian Alps, which he had hiked in a T-shirt and shorts with a new Australian friend he met at a hostel. In Vienna, he met an American expat and his wife, an Austrian, who invited him to stay at their home. “It was a nice city, and not overbustling,” he remembers.

I thought about what Vienna must have looked like then as I walked through its historic old town, its cobbled streets packed with tourists holding selfie sticks and cameras. I noticed gilded lettering on an H&M store and a McDonald’s with vaulted ceilings. The shiny screen of my phone guided me along dotted, neon blue paths that replaced the lines where paper maps had once creased. In the streets, young African and Asian men wearing boxy backpacks moved food deliveries on rented scooters — only the Uber Eats and Deliveroo logos on their bags were replaced by Wolt and Foodoo ones, global delivery companies that seem to be more popular in this part of Europe than in Paris. At a cafe called Kafka, young people worked on laptops as an enterprising Australian server rattled off the menu to five different groups of tourists in German, English, French, Spanish and Portuguese — the languages, too, blurring together.

The French have a word for the feeling of leaving home for something completely new: “depaysement.” Literally, “out-of-country-ness.” I had set off hoping to experience this sensation, the one my dad spoke so fondly of. In Vienna, I didn’t feel it — at least not yet.

The first leg of my cycling trip followed the Danube River from Vienna to Budapest — a relatively flat 120-mile stretch that weaves between field and forest in the borderlands where three countries — Austria, Slovakia and Hungary — meet. On my way out of the city, I stopped to watch a crane lifting shipping containers onto a long-distance freight train, and tried to guess the countries of origin: China, Turkey, Germany, Romania.

I entered Slovakia in the late afternoon, crossing the border without so much as a passport check. European border-free travel means that EU passport holders — which, as a binational, I am — can visit 29 countries without showing a passport. This has led to lots of freedom of movement, but also a blurring of cultural and historical differences. Crossing the border, the only thing that had visibly changed, to me at least, was that in Slovakia, unlike in Austria, gambling was legal. As if on cue, just beyond the now-obsolete border post, a run-down and somewhat seedy-looking building housed what claimed to be “the closest casino to Bratislava.”

In the capital, I used a QR code to check in to my hostel. That evening, I drank Czech beer in a dingy and surprisingly expensive pub, watching heavy rain cascade down the stone-paved streets. Nearby were a couple of French women on vacation, a British man reading on an iPad and an elderly American couple.

I left Bratislava the next morning as the heavy overnight rain turned to a light mist over the Danube.

My dad hadn’t cycled in Slovakia, which in 1978 made up half of Czechoslovakia and was under communist rule. He had headed directly south, into relatively more open Hungary. It was here, in the land of “goulash communism,” that he began to feel that sense of depaysement. Arriving in Budapest, he had used his map and compass to navigate to the center of town. In a local supermarket, he noticed that many of the products were imported, not from the U.S. but from the Soviet Union. There must have been rows and rows of “tushonka,” Soviet canned meat in Cyrillic-lettered containers, and “Lesnaya” toothpaste that came in metal tubes. Then, as in Vienna, a young couple spotted him with his bike, navigating with his maps, and they, too, invited him into their home.

In Budapest, I dodged packs of British men on “stag dos,” or bachelor parties, barreling through the city on Lime scooters as I went to meet my friend Szabolcs, a Hungarian journalist. On my way I passed a matcha shop, several brunch restaurants with 20 euro menus (about $23), and a bar that sought to channel the spirit of America’s Route 66 through neon lights, red plush booths and 1950s car deco — another attempt to repackage and profit from nostalgia for something that no longer exists, I thought. After lunch, Szabolcs told me about the current state of Hungarian politics. He walked me across the square that once housed the Communist Party headquarters. As if to underscore Hungary’s embrace of traditional values, it was recently renamed after Pope John Paul II.

During my father’s era, Hungary had faced a choice: East or West; communism or capitalism. Today’s Hungary, Szabolcs explained, was at a similar crossroads, but the choice was of another variety. Authoritarian nationalism in the figure of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán or the European multiculturalism of opposition candidate Péter Magyar. Orbán’s vision was based on a return to “traditional values,” even if through authoritarianism. Magyar’s meant embracing modernity, but possibly eroding national consciousness.

Leaving Budapest, it became easier to understand how a country like Hungary could struggle with such a choice. Though large by today’s standards, Hungary was once much larger, and the memory of imperial power still lingers. My cycling route took me through towns like Szekesfehervar, Nagykanizsa, and Nagyatad, where the faded grandeur of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which fell in 1918, remains etched into crumbling castle gates. The art nouveau facades of buildings long ago repurposed as communist-era public housing are now standing vacant.

Like fellow populists Donald Trump, Javier Milei and Vladimir Putin, Orbán has tapped into nostalgia for a “Greater Hungary” to push through a politics of exclusion and resentment. That vision felt more immediate as I pedaled west into the Hungarian hinterland, far from cosmopolitan Budapest’s matcha cafes, brunch menus and the “ruin bars” that make use of derelict buildings. Signs announcing Magyar’s closeness to Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy (“like two eggs,” the billboards proclaimed) began to disappear, as Hungarian flags proliferated. At a campsite, Hungarian vacationers put on a show of traditional music and dance. I began to feel more stares on my back as I neared Hungary’s western border.

In “Catch the Rabbit,” a 2018 novel by the Bosnian and Serbian writer Lana Bastašić, the book’s two main characters — young women whose stories are tied by a shared painful past — set off on an impromptu road trip from Mostar, in Bosnia, to Vienna. They make their way north through their formerly war-torn country, going in the opposite direction from my route. Austria, the narrator remarks at one point, staring out the window, looks a whole lot like Slovenia. And Vienna, she later says, has “plastic skin.”

For Sara, the book’s narrator, and Lejla, her friend, the rest of Europe feels fake, uniform, contrived — and, especially, inaccessible. “A different surface existed for the two of us — slippery and uniform,” Bastašić writes. For better and for worse, she seems to be saying, Bosnia is anything but plastic. It grabs you by the guts.

My father didn’t make it to Bosnia. Instead, from the Hungarian border, he continued west, riding rolling, golden hills all the way to Zagreb, the Croatian capital. If there was a highlight of my dad’s trip, he would later recall to me, it was cycling this stretch of agricultural backcountry, then part of Yugoslavia, which under Communism was composed of six federated republics, Croatia being one of them.

He crossed into eastern Croatia at sunset. The scene, he remembers, was poetic: a bucolic landscape, peasants toiling in the fields and an old locomotive chugging along rickety tracks. “To my left, the freshly cut fields were dotted with workers dressed from another century and using rakes to bring in the wheat,” he remembers. “It was like a Millet painting.” He cycled, alone, along small roads, feeling the wind at his back. As he rode alongside a train, he caught the eye of the conductor, who tried to race past him. The two of them took turns flying past one another — my dad passing the train on the downhills and the conductor catching up to him on the uphills. Finally, as the tracks curved away from the road, the conductor smiled and waved at my dad, and happily began tooting the horn as he turned the corner and rode out of sight. “It was a dream that would last a lifetime,” he says.

I made a beeline for Bosnia — or, as Bastašić describes it, “the dark heart of Europe” — hoping I might find some traces of the former Yugoslavia, the one that my dad remembered so fondly, a country of paradox and peril.

In 1931, the historian and activist Robert Seton-Watson, a proponent of the formation of Yugoslavia after World War I, wrote that Bosnia-Herzegovina had “always been the focusing point, and sometimes the battle signal, of the Jugoslav national movement.” Not only was this the “geographical centre” of the Yugoslav territories, it was “the dividing line between the religious and cultural influences flowing from Rome and Byzantium.”

During the hottest week of the year, I chopped a diagonal line across the country. Riding along busy highways to avoid remote mountain paths populated with bears, I entered the Serbian-speaking part of Bosnia, the Republika Srpska, at Gradiska, and exited near Gornja Prisika, in Croat-speaking Herzegovina. On a hot day, I crossed my first non-Schengen border on my bike — unsure whether to hop off and walk or enter with the cars; I thought the border agent might ask me what in the world I was doing, but he simply stamped my passport (European citizens are guaranteed visa-free travel up to 90 days) and impatiently waved me through. The cycling conditions were terrible and the weather even worse, but for perhaps the first time on my trip, I felt like I had left Europe behind. And I loved it.

Here, the continent I thought I knew receded swiftly into the distance. The former Ottoman outpost revealed a skyline where minarets and church steeples rose side by side, punctuated by the omnipresent Coca-Cola logos that had proliferated in the wake of communism’s collapse. Here, I enjoyed simple pleasures: cevapi, grilled mince sausages; burek, the flaky pastries stuffed with meat or cheese; and rakia, a potent plum brandy that marked every toast.

It was in Jajce, a small city in the middle of the country, that anti-fascist partisans came together in 1943 to form the National Committee of Liberation. They named Josip Broz, or “Tito” — the country’s future dictator — as the de facto leader of the resistance government. And it was here, in Bosnia, that the country splintered into sectarian violence in the 1990s, as Bosnian Serbs led by Radovan Karadžić and backed by Serbian warlord Slobodan Milošević embarked on a mission to ethnically cleanse the country of Muslim Bosniaks and Catholic Croats.

When I arrived in Jajce, I looked around for traces of Tito’s Yugoslavia, which had tried, ultimately unsuccessfully, to unite these different people and religions. All I found was a Google Maps landmark called Tito’s Hill. During the Yugoslav era, the trees on this hill had been chopped down so as to spell T-I-T-O. At the time, the hill was a major tourist attraction, but over the years nature had done its best to erase the work of people. By the time I arrived, it was simply a hill.

The Slovenian author Brina Svit, in her book “Moreno,” calls Yugoslavia “a brief history of impossible love.” The federation broke apart violently in the 1990s. Croatia, which is part of the EU and where I was headed next, seemed particularly keen on distancing itself from that history.

On the Croatian coast, I reconnected with my dad’s journey. In 1978, after bypassing Bosnia, my dad cycled the coast road from Split to Dubrovnik. This stretch, too, he remembers as uncrowded, picturesque, alien. In front of him, the sea and sky formed a wall of light blue. Behind him, jagged limestone mountains rose into the distance. “I can’t even remember a car passing me as I rode down the coast,” he says. “It was like being alone with the whole world in front of you and the whole world behind you.” The only tourists he saw were a group of British retirees, who had stopped their bus at a scenic overlook to take a picture. When he told one woman about his solo bike trip, her response was unexpected: “How could you do something so antisocial?” she scolded.

On one of those nights, he remembers camping near the beach and meeting a group of Yugoslav college students on vacation. They reveled in the relative peace and stability that reigned in Yugoslavia, which had broken with the Soviet Union and was trying to chart a third path between communism and capitalism. “When Tito dies,” they warned, presciently, “this will all end.”

In the center of the Croatian city of Split, chiseled young men wearing tight-fitting Hugo Boss T-shirts and sunglasses drank expensive cocktails on party boats. Women had lip injections and wore tight, leather skirts. I saw several Teslas. The coast road my dad had cycled was now a traffic jam that seemed to last until Montenegro. In Dubrovnik, where my dad had once walked alone along the walled city’s ramparts, I found not one, but two concept stores that sold nothing but rows and rows of plastic ducks.

Only the “Red History Museum” in Dubrovnik stands as an interactive mausoleum of the past. There’s a Yugoslav living room with records and a worn typewriter, a K67 kiosk — one of the small vending stalls that once littered the country and are now mostly in disrepair — and, of course, a famous Yugo car that you can sit in. These cheap 1980s clunkers were produced by Zastava Automobiles and sold abroad, including in the United States, in a show of Yugoslav soft power. “Where I go, Yugo,” the tagline read.

Montenegro, where I cycled next, seemed ready to follow Croatia’s lead. The brutalist Jugopetrol building in Kotor, which used to host the offices of the state-run oil company, had been gutted in preparation for a project to renovate it into a five-star Marriott hotel. Jugopetrol still exists, but the company was bought by the Greek company Hellenic Petroleum in 2014, and its offices were relocated to the capital, Podgorica.

During the Yugoslav era, Montenegro, one of the country’s six republics, remained the closest to the Soviet Union, even after Tito famously broke with Stalin in 1948. Montenegrin elites often had family or historical ties with Russia, some dating back hundreds of years to when Moscow helped them fight off Ottoman influence.

These days, as I found on an early August weekend, Montenegro’s beaches are inundated with Russian tourists — unable to travel to most of Europe, but happy to take advantage of the Adriatic’s azure waters from just next door, where they spend an average of $120 per day.

Though Montenegro’s President Jakov Milatović ran on the platform of the Europe Now Movement, the country whose capital was once known as Titograd doesn’t seem to mind the cash inflow.

If there was one country on my route that particularly intrigued me, it was Albania — a place my dad had not been able to visit.

The closest Steve came to Albania was on the other side of the Adriatic. From the deck of a ferry, he watched a silver sun rise up from behind distant mountains shrouded in fog. Forty-seven years later, I crossed into Albania by land, wondering what this once-isolated country had in store for me. Would it be like Croatia and Montenegro, with cruise ships docking at every port and roller-bag restrictions to stem noise complaints? Or would the Kosovo War of the late 1990s have left Albania with the veneer of Bosnia, still recovering from trauma?

Unbeknownst to me, the tone had already been set. “Albania Seizes Its Moment in the Sun,” The New York Times travel section proclaimed in an article published as I was cycling through the country. The article kept showing up on my Instagram feed.

Initially, I did not come across any shops selling plastic ducks. Rather, Albania welcomed me with the strong odor of gasoline and burnt crops. In Shkoder, old men played dominoes as the sound of a muezzin rang out in a municipal park filled with teens on their phones and mothers in headscarves pushing strollers.

I visited the Site of Witness and Memory, a modest and mostly empty museum where visitors learn about the more than 5,000 Albanians killed by firing squad under the dictatorship of Enver Hoxha, thanks to a film screened on a loop, showing grainy images set to dramatic music.

Albania officially embraced multiparty democracy in December 1990, and with it capitalist development. By then, “small pieces of the [Berlin] Wall were already being sold in the souvenir kiosks of recently unified Berlin,” writes the Albanian political scientist Lea Ypi in her memoir “Free: Coming of Age at the End of History.” But in Albania, the path to capitalist development didn’t proceed smoothly: The economy cratered as desperate Albanians, once welcomed in neighboring Greece and Italy as dissidents, were now humiliated and barred from entry, considered unwanted migrants and refugees. In 1997, the country nearly descended into civil war.

Twenty years later, the Albanians I met were still not convinced of the path they wanted to take. At a campsite in the Patok nature reserve, I met a group of young Albanians who took me under their wing for the evening. As the sun dropped low in the sky, we piloted a small boat across a shallow lagoon to a deserted beach to swim in the shallow waters. Later that night, over home-brewed beer and locally caught fish, they told me about their fears of mass tourism. Where would all of that money go in a country plagued by corruption, and what would happen to places like the one we were in?

As long as we don’t start killing each other again, one of my new friends — himself an Albanian Kosovar — pontificated, everything would be alright.

It was not until I reached Fushe-Kruje, a town in the center of Albania, that I started to realize the futility of my mission, and the disappearance of my dad’s world. I was sitting at the George W. Bush cafe overlooking the George W. Bush bakery. Below me, I watched as an enormous traffic jam of 1980s-era cars, motorcycles, bicycles and rickshaws rounded the George W. Bush statue. The statue shows Bush wearing a casual button-down and no tie. His sleeves are rolled up as he raises one arm, bent at the elbow, a sheepish grin on his face. Behind the Republican former president, artfully placed, are the offices of the center-left Albanian Socialist Party.

In 2007, Bush became the first U.S. president to visit Albania. Why Bush decided to go to Fushe-Kruje, specifically, seems to be a mystery. What’s certain is that when he arrived, he was greeted as a hero. In pictures from that visit, Bush is surrounded by crowds of people waving American flags. To the inhabitants of this 15,000-person town, whose only other claim to fame is its cement factory, Bush was the incarnation of freedom and promise in a moment of great transition.

As Ypi writes in “Free,” the fall of communism and the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc was viewed by many as the victory of one world over another, of capitalism over communism, freedom over tyranny. But does history really progress as simply as that, she asks?

In Fushe-Kruje, I felt that the world I’d been searching for was gone and would never come back. George W. Bush’s smiling and eternal bust — a symbol not only of U.S. hegemony, but of the globalized world the so-called American century ushered in — was standing there, confidently, as ultimate proof.

Become a member today to receive access to all our paywalled essays and the best of New Lines delivered to your inbox through our newsletters.