I spent the summer of 2021 in the company of old white Frenchmen.

Dead men, that is, the type of men whose names and statues mark the streets of Paris, Lille and Marseille, but whose thoughts and words are buried in the creases of history books and the corners of dusty archives. Imagine, if you will, the Robert E. Lees and Christopher Columbuses of France — men who were once celebrated as symbols of achievement and sacrifice but whose stone edifices now stand as reminders that the violence of the past still lives among us.

In my role as a doctoral scholar, a journey to the government archives in the French city of Nantes felt like a mission to discover grime-covered treasures to plump up my dissertation on the French conquest of Morocco. As a Muslim woman of North African descent, that journey became very personal.

I hadn’t expected it to be. Born to Egyptian parents, I have had primarily academic ties to Morocco. In fact, I’d avoided research on Egypt because more often than not, it hits too close to home. Rather than be the Muslim woman who does only Muslim woman-ish things, I’d developed an interest in military history and security politics — fields that, across most US campuses, are dominated by middle-aged white men.

Yet the identity that I felt was irrelevant to the work I was doing followed me everywhere I went.

Before booking my trip to France, I scoured the Google-verse for an answer to one important question: “Can I access government archives while wearing a headscarf?” It seemed to me a legitimate concern, as only a few weeks earlier, French legislators had been debating new measures that would restrict the access of hijab-wearing women to certain public spaces. The irony was not lost on me: My access to the history of the lands and peoples to which I belonged might be denied by the structures and biases that shaped some of the darkest chapters of that history.

But luckily for me, that wasn’t the case. Not yet anyway.

One plane ticket, one Boston airport security hand swab (I resisted, as I always must, the indignant urge to ask the TSA officer why it was necessary for me to pat my head first — was the assumption really that any potential explosives must be hidden in the folds of my invisible hair?) and one additional “random” interrogation later, I arrived in Nantes.

I made it through an obstacle course of prejudices to be delivered to a place where I could meet with the ghosts of some of the men who helped create them.

Nantes is a good place to think about history. Situated on the banks of the Loire River just 30 miles from the Atlantic Ocean, the city was once a major port in the transatlantic slave trade, responsible for the transfer of more than 500,000 African slaves across its shores, or approximately 43% of the French share.

It’s also a city whose charm is defined by its quirkiness: Every corner boasts a bizarre-shaped building, an architectural innovation, a moving art installation. The streets, the parks and the museums are all designed to exude a sense of adventure, no doubt inspired by the city’s proximity to the ocean. Nantes was the muse that gave us Jules Verne classics like “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea” and “Around the World in Eighty Days.” Verne — whose memorable characters I have to thank for my improved French — was enamored of the ships that docked along the Loire. No doubt the 19th-century novelist also knew that many of those used to be slave ships.

Northwest of the river is another piece of history, locked within the walls of the Diplomatic Archives of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The heavily guarded, four-story building would be my office for the next two months, home to tens of thousands of documents belonging to the French colonial administration in Morocco from 1912 to 1956. Access to the building is contingent on a daily security screening, during which a rotating set of guards pass a hand-held metal detector over your body, joke about finding weapons in your laptop bag and, in my case, deliver unprompted 15-minute monologues on the superiority of French law as compared with what they understand to be Islamic sharia.

Once inside, I spent hours on end combing through dusty boxes exploding with government memos, official correspondence, research documents and intelligence reports. Every day felt like I was listening to a one-sided conversation, one that dated back at least 100 years. The speakers — explorers, officers, administrators — were long dead, but the topics were painfully familiar.

For instance, there was the perplexing question of whether Moroccans, specifically Muslims and Jews, should be allowed access to public swimming pools. It was a debate that, according to a thick folder of correspondence I found in a box labeled “indigenous policy,” occupied the energy of a wide gamut of officials, from municipal bureaucrats to high-ranking officers, from 1936 to 1944. After repeated petitions and pleas from Moroccan Muslim and Jewish communities to be allowed the same rights as Europeans, the solution, in most cases, was to designate special hours for non-Europeans and occasionally, where Muslims were concerned, to require a special bathing permit.

Well, I certainly hadn’t tried to pack a hijab-friendly swimsuit on my way to Nantes; even among the living, there are plenty — including a fair share of French politicians — who would deny me that choice.

Then there was the problem of the inherent fanaticism of Muslim populations and how to civilize them, “à la française.”

French colonial administrators, like many of their counterparts in the 19th and early 20th centuries, were obsessed with a “scientific” approach to imperial rule. Subject races were an object to be studied as much as they were a population to be conquered. Every custom was a discovery; every movement, however mundane, was worth scrutiny. I learned, for example, the name, history and average following of every Sufi religious order in the country. I also learned that on one crisp September afternoon in 1940, the Moroccan sultan — the religious, if not effective, head of state — apparently went roller-skating on his terrace, to the astonishment of officers tasked with his surveillance.

As I chuckled over the meticulous level of detail in these little pieces of history, I considered keeping count of how many times I read the word “fanatique” in the thick volumes of research on Muslims and Islam. It didn’t take long for me to decide that the task would be too arduous.

And of course there was the phrase that I, as an Arab and a Muslim, had learned to fear: “les terroristes musulmans” (read: the anti-colonial movement).

It was a phrase I’d been repeatedly told was the rational price I had to pay for the crimes of others. “Can you blame them?” I’d often hear. “Look at the terrible things Muslims like us are doing.” It’s easy to embrace the labels and stories others tell us about ourselves. But here I was, in possession of evidence that the T-word had been in heavy circulation at least a century before 9/11.

As I continued to scour the grime-filled documents, I heard the racist and disdainful undertones piercing through the faded texts just as clearly as I read the bold signatures of their mustachioed authors. I felt both empowered and defeated by these one-sided conversations — empowered by the knowledge I was amassing to write my own narrative and defeated by my inability to talk back to these dead men with their overconfident ink strokes.

Along the Loire River is Europe’s largest memorial to the abolition of slavery. Built in Nantes as a way to acknowledge the city’s violent past, it has been celebrated by many as the first memorial of its kind. After days spent rifling through stained piles of documents and rusty paper clips, I searched for it along the esplanade, my feet unknowingly stepping over hundreds of small glass inserts carrying the names of slave merchant ships that once docked on these shores.

I was puzzled. Google Maps was telling me I had arrived, but the memorial was nowhere in sight.

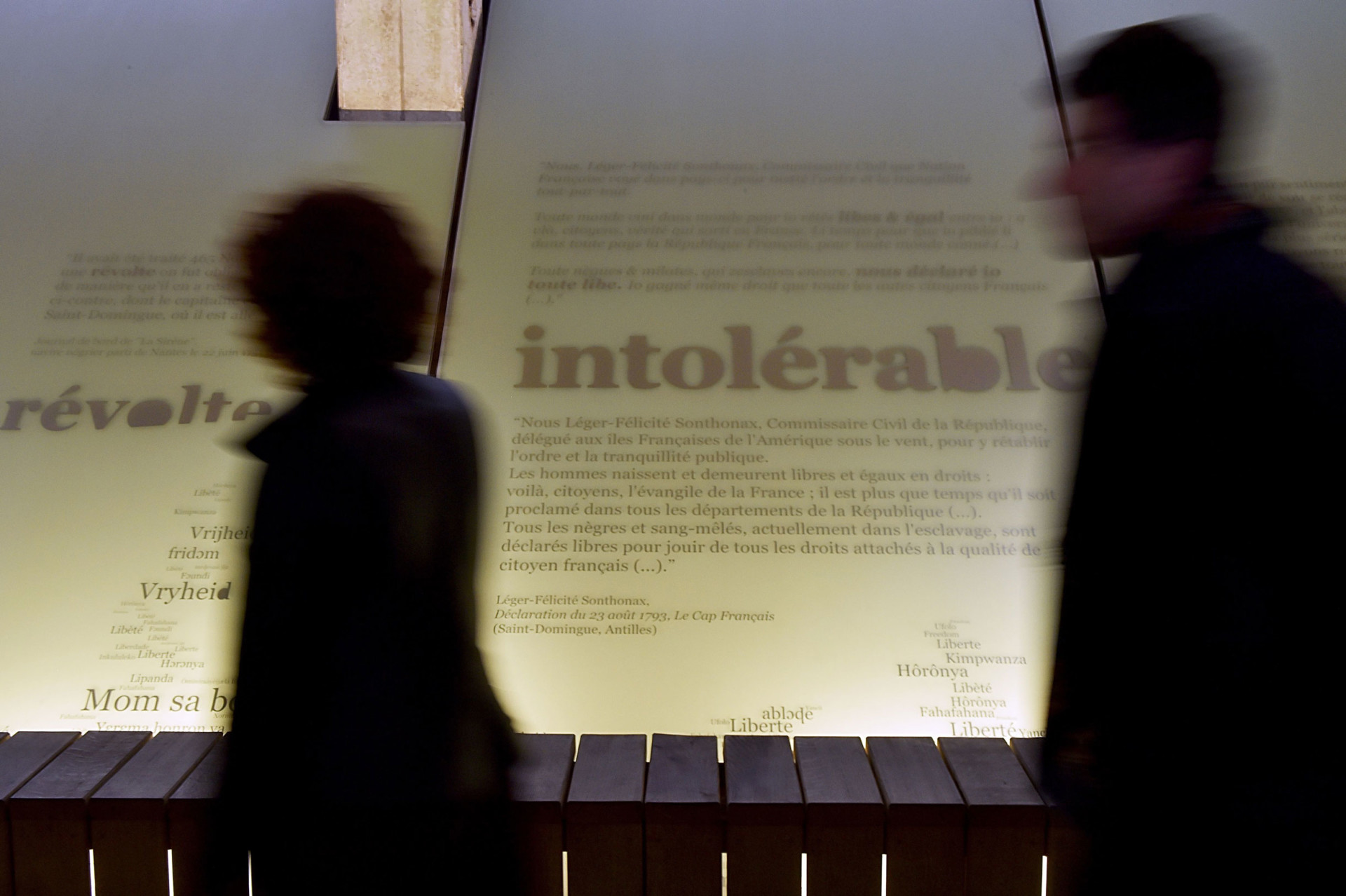

The bulk of it, I eventually discovered, was located in a 440-yard-long underground passageway, designed to replicate the underground confines of a slave merchant ship, but effectively hidden from sight and only visible to those who seek it. Inside the passageway was information about the magnitude of the transatlantic slave trade and a timeline of its abolition, followed by a series of glass panels featuring the word “freedom” written in different languages, a quote from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and inspirational words from renowned thinkers, politicians and artists. It reminded me of the quotes my undergraduate students place as epithets at the beginning of their essays: something deep and profound, yet often disconnected from the rest of the text.

But what I felt wasn’t inspiration; it was despondence.

Though perhaps well-intended, the focus on the triumph of the abolitionist movement seemed to me to reduce history to a moment in the distant past. The memorial wasn’t a reminder of the violence and suffering of the more than half a million people whose feet were shackled on its very shores, but a story of progress. “Good for you,” it seemed to say, complete with a 440-yard-long pat on the back for closing a grim chapter of history.

I knew this to be wildly misleading: The slave trade continued long after abolition, and the legacies of slavery long after that. As I stared at the date on the timeline marking the official abolition of slavery in France — 1848 — I recalled a document, written in 1950, which I’d found among the dusty boxes at the archives. In it, a French official discusses what he believes are compelling reasons in favor of allowing Moroccans to continue to maintain slaves in certain parts, a gesture of tolerance toward the “archaic” customs of their overseas subjects.

Custom and tradition, I had learned, were malleable concepts, and convenient ones too. Marshal Hubert Lyautey, the first and longest-serving resident general of France in Morocco and the man whose instructions and correspondence I’d spent countless hours reading, was a big fan of tradition. Unlike his assimilationist colleagues in other parts of the French empire, he embraced, reified and repurposed cultural and religious traditions as tools to secure colonial rule.

Some 240 miles northwest of Nantes is a material testament to this legacy: the Grand Mosque of Paris, located in the city’s Latin district. The first stone of what would become one of the largest mosques in France was laid in 1922 in recognition of Franco-Muslim friendship and the hundreds of thousands of Muslim soldiers — most recruited from the empire’s colonial possessions — who lost their lives while fighting for France during World War I.

Officially, the construction of the mosque was subsidized by the French state, as well as the governments of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, all under varying forms of French rule. Unofficially, as the time-worn sheets of paper at the Diplomatic Archives indicated, colonial officers had also been instructed to solicit funds from their North African subjects, a task over which some officers expressed some scruples: Times were tough, harvests were poor, and some farmers might misconstrue the request as a mandatory tax. But the mosque was important to French imperial policy.

Despite a near identical decorative style, what struck me when I visited the Grand Mosque was the difference between this and other religious sites I had visited in Morocco. Inspired by the architectural design of the ancient Al Qarawiyyin mosque in Fez, it bears the same mosaic tiles and arabesque reliefs I’d seen at mosques and palaces across Morocco and Andalusia. However, unlike the majority of Moroccan religious sites, Muslims and non-Muslims alike could access it. It also came with an annex of Moroccan-themed businesses, including a “hammam” spa, a tearoom, a restaurant and a gift shop, all of which gave the mosque complex a commercial and touristy feel that overshadowed its religious and communal functions.

During my first visit to Morocco, it was confusing to me that non-Muslims were banned from entering the majority of Muslim sites. Growing up in Egypt, I was accustomed to an open-access policy, as long as visitors treated the sites with respect. And as a Muslim myself, an entry ban seemed to contradict the welcoming spirit of Islamic teachings. But by the time I made my way to the Grand Mosque, I had learned that the prohibition was in fact a policy instituted by Lyautey himself. In proclaiming to preserve religious practice, he had invented it. And now, some 100 years later, millions of Muslims embrace it as a tradition of their faith.

As I stood alongside a handful of tourists admiring the serene beauty of the mosque courtyard, it occurred to me that this monument and its bustling annex of “ethnic” commercial experiences was, like Lyautey’s non-Muslim ban, also a product of France’s complicated history with Islam and its attempts to define it in more palpable terms.

The journey that began as a search for a doctoral thesis had morphed into a series of accidental discoveries about my own relationship to the forces of history. What dead men will inadvertently tell you is that history is durable; it lingers long after the moment we decide to put it behind us and shapes not only the world in which we live but also the narratives we are told — and sometimes believe — about ourselves. It is this very durability that sends chills down my spine every time I come across a reference to the “beastly” features of Black men or the “barbaric” nature of Arabs: These words feel more familiar than they should. They’re so painfully old.

And yet it seemed to me that our instinct, from Nantes to Boston and everywhere between, is to relegate history to the distant past.

In Nantes, the clock has been reset with the abolition of slavery, and across the world, monuments to the heroes of yesteryear were being vandalized, removed and even beheaded. In the United States, nearly 100 Confederate monuments have been removed in 2020 alone, and only a few miles from my own home, the city of Boston was discussing plans to replace a decapitated statue of Christopher Columbus with a monument celebrating the Italian immigrant community in the North End. Whether we choose to erect new memorials or topple old ones — to preserve memory or to erase it — the message seems to be: replace old with new.

This material reset can be comforting: It gives the impression of a clean slate, of a division of history into the darkness of the past and the promise of the present. But we need only look to the rubble of empire to see that the past still lingers. As I strolled along the esplanade by the Loire River and through the streets of the Latin district, I wondered what a more honest material testament to the past would look like, one that doesn’t feel so disconnected from our lived experiences.

Perhaps what we need, uncomfortable though it may be, is to live and breathe history for as long as it takes for it to stop being familiar. We need to let go of the notion that memorials must somehow celebrate the end of things or that memory is to be enclosed in archives and memorial sites, accessible only to those with the interest and privilege to seek it. We need to recall the old street names along with the new, the monuments that were vandalized along with those that replaced them. We need to build memorials that not only honor the victims of violence but also record that somewhere across town, the perpetrators of violence still stand tall in casts of bronze and stone.

If my summer with dusty, long-dead Frenchmen taught me anything, it’s that we need not confine history to a single moment in the past or to a series of pages that can neatly be archived. Instead we must recognize it for the mess of undetachable layers that it is. Perhaps only then will the bold signatures of mustachioed dead men start to fade away.