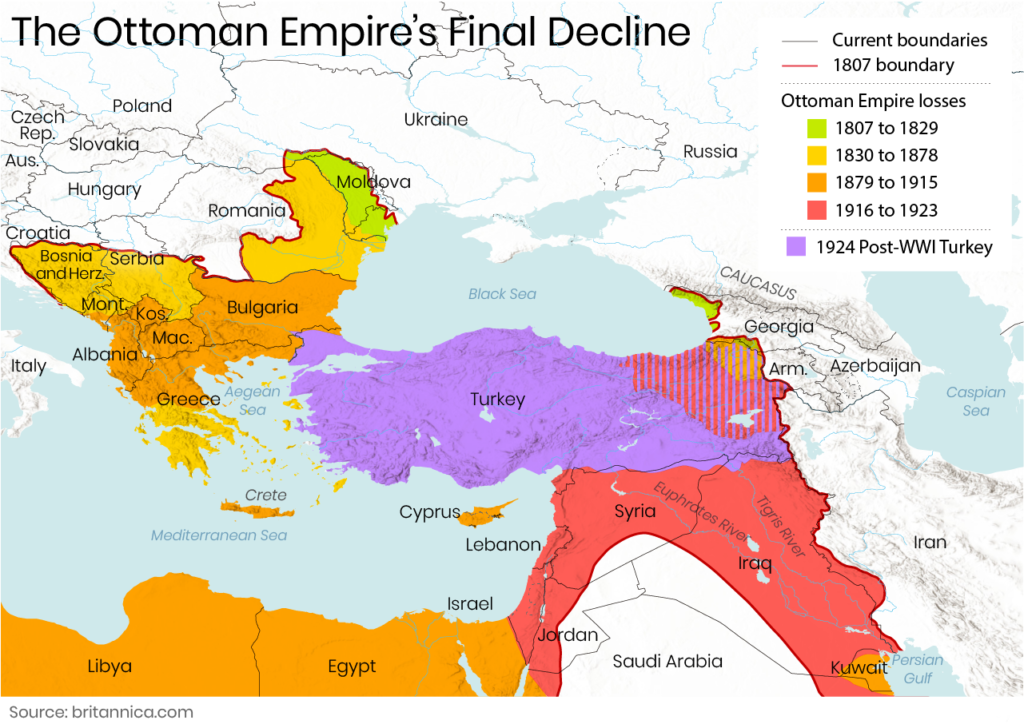

In the summer of 2014, the Islamic State released a dramatic video presenting its destruction of a sand berm along the Iraqi-Syrian border as “the end of Sykes-Picot,” a notorious 1916 agreement believed to have laid the groundwork for the borders of much of the modern Middle East. Even today, few people are aware that the fortifications ISIS used to symbolize a century-old political order were likely just a few decades old. In fact, the Iraqi-Syrian border was only delimited by a League of Nations commission in 1932, and it remained open for nomads to cross relatively freely until Iraqi-Syrian relations turned hostile in the 1980s.

While everyone has their own preferred narrative, many observers, from academics to reporters and memoirists, have all come to see the Middle East’s post-Ottoman borders as a particularly ugly embodiment of the way colonialism, nationalism and the 20th-century state dismembered a once-coherent space. Preexisting social ties were severed, trade networks were dismantled, and families were torn apart, all in the name of modernizing ideologies that refused to recognize the region’s interconnected reality. As a result, these new lines have come to symbolize the blind arrogance of those who reordered the region with so little regard for the lives they would ruin.

But it would be a mistake to assume that these borders sprung fully formed from the heads of the colonial officials and nationalist leaders who drew them, with barbed wire, checkpoints, and minefields inevitably following their pens across the map. To a surprising extent, the political regimes that built the new borders of the Middle East after World War I acknowledged and tried to mitigate, if only for their own cynical reasons, the potential for disruption. In the 1920s and ‘30s, many of the region’s borders were considerably more open than they are now. It was not merely the creation of borders that proved disruptive but, more crucially, the political tensions between governments on both sides that subsequently led to their closure.

Consistently, borders drawn in the immediate aftermath of the First World War took on a life of their own later in the 20th century. Political and military disputes gave lines that were initially intended to be quite permeable the fortified, disruptive character we associate with them today. Bad neighbors, it seems, make bad border regimes, and bad border regimes disrupt societies. It is always tempting to blame today’s problems on the ideologically driven failure of our predecessors to anticipate them. The more damning possibility is that earlier generations of leaders or thinkers may have anticipated the challenges they faced quite clearly but still failed to find a lasting solution. Recognizing this doesn’t absolve our predecessors, but it can help us avoid their mistakes.

Among other things, the text of the Sykes-Picot agreement contained several clauses aimed at minimizing the impact of any new borders it might create. Maintaining preexisting networks – of trade, at least – proved to be important for imperial interests. It was agreed, for example, “that Alexandretta shall be a free port as regards the trade of the British Empire,” meaning “that there shall be no discrimination in port charges or facilities as regards British shipping and British goods.” France was to be given similar rights in Haifa and, to further facilitate trade, there would “be no interior customs barriers between any of the above-mentioned areas.”

When Americans put forward their proposal for the region in 1919, they saw similar benefits in maintaining such ties. The King-Crane commission report, despite presenting itself as a corrective to European imperialism, ultimately concluded that imperial rule could help smooth the challenges posed by self-determination and maintain smoother relations across borders. In calling for the same mandatory power to control Syria and Mesopotamia, for example, the commission claimed that this would serve to “promote economic and educational unity throughout Mesopotamia and Syria.” This, they believed, was necessary to “reflect more fully than ever before, the close relations in language, customs, and trade between these parts of the former Turkish Empire.” Likewise, the commission said of Turkey and Armenia that “[t]hose areas have been held together for several centuries and have a great number of close ties of all sorts, the delicate adjustment of which can be best accomplished under one power.” Making modern states, in other words, did not require abandoning the benefits of the old order.

Several years later, the newly created League of Nations was called on to adjudicate a dispute between Britain and Turkey over who should control the former Ottoman province of Mosul. The League’s final report on the subject helps reveal the extent to which the diplomats who embodied the modern nation-state system also believed borders could and should be porous. In making their cases to the League, both Britain and Turkey insisted that if the new Iraqi-Turkish border was drawn in the wrong place it would cause deep and traumatic social and economic disruption. But if it was drawn in the right place, they insisted, these disruptions would be minimal and could be managed with an attentive and responsible border regime.

The League, for its part, seemed to think that whoever got Mosul and wherever the borders were drawn, the consequence wouldn’t be that bad. As evidence, the League’s decision first cited an agreement already in place for the Persian frontier stipulating that “Turkish tribes which are accustomed to pass the summer in these valleys at the source of the Gadyr and Lavene will continue to enjoy the use of these pastures as heretofore.” (A later League report on Iraq-Syria also cites a 17th-century agreement between Norway and Sweden regarding nomadic migration in Lapland, with the caveat that camels and reindeer were somewhat different beasts.)

About free movement for nomads, the League concluded “that the statements of the British Government regarding the difficulty of tracing a frontier across territory over which the Bedouin roam in search of pasture is rather exaggerated.” Why? Because the British government’s own reports on the administration of Iraq showed that it had been possible to do so successfully “even on the Iraq-Syrian frontier.” The League was equally optimistic that provisions could be made to maintain trade ties wherever the border was drawn. “If the disputed territory is assigned to Iraq,” the report argued, “its inhabitants should be given full freedom of trade with Turkey and Syria.” To make this possible, “facilities should be afforded to the Turkish frontier towns to use the Mosul route for exporting their produce and importing manufactured articles.”

Even more telling is that, when it came to both trade and nomadic migration, the League assumed that political forces, not borders, would be the main factor in transforming traditional patterns of life. Forcible resettlement of nomads by both the Turkish and Iraqi states, they suggested, would curtail migration, while the construction of new railways and roads would transform economic patterns in the region. In other words, other aspects of the modern state would prove more disruptive than the borders that came with them.

When European imperial powers drew borders in the region, they consistently included provisions to accommodate the web of economic and social relationships these new lines would cut across. As Robert Fletcher concludes in his study of interwar borders, “Freedom of grazing and nomadic migration was written into all major boundary agreements in the 1920s.” Moreover, he argues, “These terms were assiduously observed by local frontier officials, even to the point of risking conflict with demands from the center.”

The language in many of these agreements was standard and relatively expansive. The 1926 Anglo-French “good neighbor” agreement, for example, states:

“All the inhabitants, whether settled or semi-nomadic, of both territories who at the date of the signature of this agreement enjoy grazing, watering or cultivation rights, or own land on the one or the other side of the frontier, shall continue to exercise their rights as in the past. They shall be entitled, for this purpose, to cross the frontier freely and without a passport and to transport, from one side to the other of the frontier, their animals and the natural increase thereof, their tools, their vehicles whatever the mode of traction, their implements, seeds and products of the soil or subsoil of their lands, without paying any customs duties or any dues for grazing or watering or any other tax on account of passing the frontier and entering the neighboring territory.”

As to how these agreements played out, it seems that across the British-French frontier that divided Syria and Lebanon from Palestine, the impact of the new border was initially minimal. Cyrus Schayegh writes that “travel documents could be obtained at minimal cost from French administrators,” but even where new border posts were erected, “[p]eople mostly continued to cross between these posts without papers.”

Similarly, Asher Kaufman describes Zionists freely crossing the border between French and British mandates in order to hike Mount Hermon and notes that as of 1941, according to one participant, “these trips did not require cross border permits because the border was wide open and they never met a Lebanese or Syrian policeman.” Sometimes even the nominal requirement for documents was waived, such as with a provision declaring that “pilgrims making the annual pilgrimage to the Nabi Yusha marabout at the end of Ramadan shall be exempt from formalities of a passport or laissez-passer.”

Subsequently, both Schayegh and Kaufman cite a series of political developments as being decisive in bringing this once-open border to a close. In 1938, the British built a fence to stop gun-runners following the outbreak of the Arab revolt. Then, in 1941, they deployed the Transjordan frontier force to stop Jewish immigration to Palestine. Finally, in 1948, two and a half decades after its demarcation, the border closed more dramatically, taking on the impassable and militarized character it has today.

The Turkish-Syrian border experienced a similar transformation. The story is perhaps most familiar to Turkish audiences from the 1999 film Propaganda, which shows the disruptive impact of the new border that came into being with the Turkish annexation of Hatay in 1939. The film offers a dramatic parable of neighbors and lovers separated as their village is torn apart by an arbitrary and unnatural line. But in fact, after 1923, the Turkish-Syrian border was relatively open until the ongoing conflict over Hatay itself caused both sides to gradually close it.

The initial agreement governing the Syrian-Turkish border included similar clauses to those above. Moreover, a Turkish train line extending east to the city of Nusaybin crossed the border at several points, an arrangement whose legal and logistical challenges Ankara found relatively minor in comparison with the track’s technical limitations. Then, in the years leading up to Hatay’s annexation, the French set up new border controls to try to prevent the infiltration of Turkish guerrillas seeking to liberate the province. Sarah Shields relates how, after 1938, the Turkish government imposed new tariffs and transport restrictions as part of a deliberate effort to sever the region’s ties with Syria and incorporate it into Turkey.

In World War II, wartime security concerns led to new restrictions, with religious minorities in particular carefully monitored amidst accusations of espionage. Finally, in the 1980s, after Turkey’s Sept. 12 coup, the Turkish government for the first time laid mines along the border in order to prevent potential Syrian support for illegal left-wing groups in Turkey. Mining the border half a century after it was first drawn showed the deadly and disruptive result of Cold War politics, as well as Turkish-Syrian tensions arising from the Hatay dispute.

Imperial nostalgia, of either the Ottoman or European variety, remains distinctly less popular in the Middle East than in either Turkey or Europe. But there is one realm in which the region’s earlier political order appears undeniably more humane. With people from Belgrade to Basra now cut off from each other by a series of borders – and all too often dying while trying to cross them – it is hard not to romanticize an era where these divisions did not exist.

To blame Europeans for creating many of the Middle East’s problems yet simultaneously recognize that they presided over a period when you could simply board a bus from Haifa to Beirut is not necessarily paradoxical. Rather, it helps articulate the difficulty, and possibility, of resolving these problems today. We must constantly struggle to overcome the injustices around us while remaining constantly alert to the risk of creating new ones. Nationalism promised former Ottoman citizens self-rule, but instead brought them continued oppression in smaller states. Likewise, the resistance movements that proved necessary to overthrow European colonial rule carried with them the seeds of the conflicts that compounded some of colonialism’s worst features.

To date, forcible attempts to redraw borders have simply added to the misery of those trapped or divided by them. Ideologies such as pan-Arabism or pan-Islamism, cast as a corrective to these borders, have also faced resistance from those worried about the new disruptions they would bring. And for Palestinians in particular, the promise of a two-state solution has been cynically manipulated, leaving them with no state and no rights.

There is a more optimistic side to this history, though. Looking back at the evolution of border regimes over the last century serves as a reminder that we can work to transcend them without eliminating them completely. We don’t need to change the lines on the map to mitigate their human toll, whether by making them easier to cross or helping people fight for their rights within them.