What drives groups to commit shocking acts of political violence on ordinary people?

This question has renewed urgency in the wake of the storming of the United States Capitol building on Jan. 6, and the rise of white nationalism at large. Such acts were said to have been ideologically driven by a conspiracy theory, peddled by the former president and online groups, about a covert, bipartisan government operation that altered the results of the 2020 presidential election and falsely declared Joe Biden the winner. Its adherents were committed to stopping what they saw as a stolen election by an oligarchic “deep state” and restoring democracy.

As a cognitive scientist, I have been studying the drivers of political violence by interviewing and surveying current and former members of jihadist, white nationalist, and conspiracist groups like QAnon. My colleagues and I at the research organization Artis International have also taken the novel approach of using neuroscience to understand what motivates people to kill or be killed for an idea. What we’ve found is that the “success” of these groups is largely driven by a certain kind of member within them.

People join politically violent movements for a variety of reasons and differ in their levels of commitment to the cause. Some people are ideologues and strategists who take on leadership positions. Others join for pragmatic reasons like money and security. Some people even have severe mental health issues, and these groups can exploit them. My colleagues and I have been studying a particular group of people that exist within these movements. We believe that these people make up the backbone of these groups and, more than any other member, give these groups their power. We call them “devoted actors.”

Devoted actors are those people who are willing to make costly sacrifices for a group or cause. Now, we’re not just talking about any ordinary sacrifice, like lending a helping hand to a friend to move apartments. These actions have to be truly sacrificial, like willingness to go to jail, to be beaten bloody, to lose one’s life, or even to take another’s.

These people aren’t all bad, though. Followers of Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Nelson Mandela could all be classified as devoted actors: They were willing to lay down their lives for their people and their cause. Successful movements, good or bad, contain devoted actors who put their own well-being, and sometimes that of others, on the line to advance their cause.

Devoted actors are the cornerstone of a movement — without them the whole project falls apart. Any country that is battling a violent movement at home or abroad needs to be asking itself how it should deal with these figures. And in order to do that, you first have to understand the anatomy of a devoted actor: how they are created, how they think, and how to divert their actions.

In our research, we have found two elements that are particularly important in the psychology of those who are willing to fight and die for a cause. The first is a particular kind of identity called “identity fusion.” This occurs when a person feels a visceral sense of oneness with a group. Many of us already know this exact feeling as it’s how we feel about the loved ones in our lives, such as our family. While we maintain our individual identity, we have an emotional connection to our loved ones that could cause us to move mountains to help them. Think of a mother running into traffic to save her wandering toddler. She’s willing to risk her own life to save her child. Her springing into action is a visceral response. When it comes to political violence, identity fusion is what happens when this feeling gets extended beyond our family or loved ones to something like a combat group.

Researchers at the University of Oxford conducted a study demonstrating this phenomenon with individuals who took part in the Arab Spring in Libya. The researchers embedded themselves in Libyan revolutionary battalions that were fighting against the Gadhafi regime in 2011 in order to conduct psychological studies on them. What they found was that non-frontline revolutionaries, those in logistical units, were more fused with their families than with their battalions. So, while they cared about their comrades, they did not put them on equal footing with their blood relatives. However, frontline fighters were as fused with their battalions as they were with their families, meaning the people who went out to kill and be killed psychologically came to see their battalions in the same way as they saw their families.

These findings won’t necessarily come as a surprise to anyone who’s served in the military in a war zone. There is a reason why soldiers refer to their fellow service members as brothers and sisters in arms. The threat of violence and risking one’s life for a common goal can bind people together in inextricable terms. But the making of a devoted actor has another crucial component we call “sacred values.”

These are moral values of the highest caliber. You can’t persuade someone to give up a value that is sacred to them by offering them money or other material enticements. Despite the name “sacred,” these values do not have to be religious. For some, freedom of speech or national sovereignty could be sacred. For jihadists, sacred values could include the resurrection of a caliphate or strict shariah as the rule of all lands. When someone violates your sacred values, you are unlikely to sit back and take it, especially if you have a whole group of people who also hold those values as sacred and are ready to defend them at your side.

My colleagues and I have been studying the role of sacred values in conflicts ranging from Israel and Palestine, to India and Pakistan, to Iran and the U.S., and even in the Catalan independence movement.

Devoted actors really start to take shape when we look at the interplay of identity fusion and sacred values. One of our studies in Morocco found that the combination of holding strict shariah as a sacred value and being fused with like-minded friends boosted willingness to use violence for a cause. In other words, it’s comrades and cause together that make the potent mix for self-sacrifice.

On the frontlines, fighters would choose their sacred values over their fused groups (e.g., their tribe, immediate family, etc.) and even over their families. This suggests that fusion may act as an incubator to increase devotion for a cause, but once you are really ready to give your life for your sacred values, then you would be willing to forsake your own family and even your fellow combatants. Meaning, in some cases, a devoted actor would be willing to sacrifice their comrades for the cause.

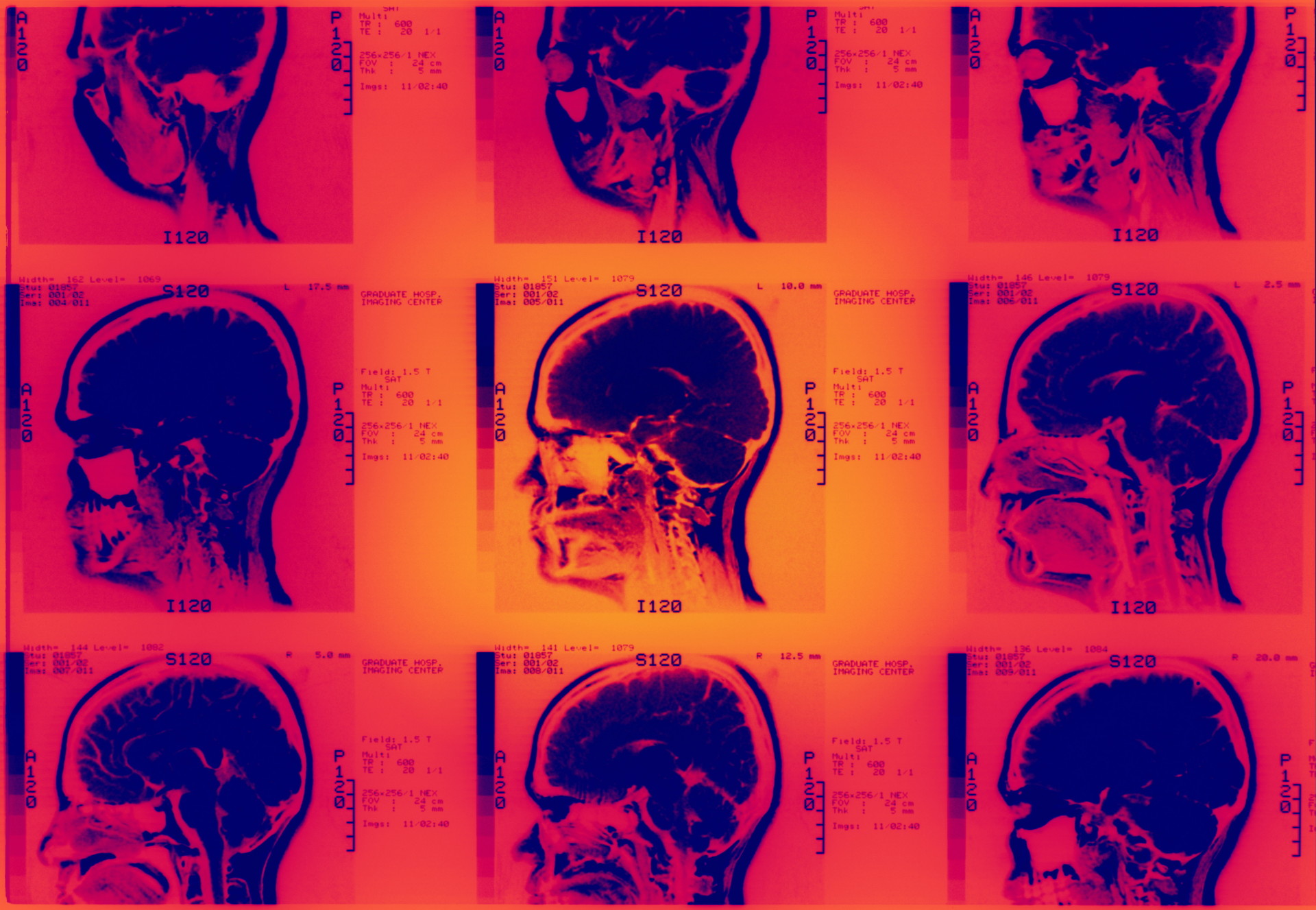

We wanted to dig deeper into this notion of sacred values and how they relate to someone willing to fight and die. Observations, interviews, surveys, and behavioral experiments can tell us a lot, but we wanted to go beyond the standard qualitative and quantitative methods. So, we scanned the brains of jihadist supporters in the first-ever neuroscience studies on a radicalized population.

In the first study, we scanned the brains of 38 young Moroccan men living in Barcelona who endorsed violence for causes championed by jihadist groups. Before being scanned, the men played a virtual ball game with three ostensibly Spanish players. Half the participants were randomly placed in the control condition; they passed the virtual ball to the three Spanish players who would then pass the ball back to them. The remaining half of the participants played the same game, except in this group the Spanish players started by passing the ball to the player of Moroccan origin, but after a few passes they stopped passing it to our participant and only played among themselves, thus excluding our jihadist sympathizer.

All participants then got into the functional MRI (fMRI) to have their brains scanned while evaluating their willingness to fight and die for their sacred and non-sacred values (which we ascertained beforehand using psychometric measures). We found that social exclusion caused parts of the brain associated with sacred values to activate even for non-sacred values. And they increased their explicit willingness to fight and die for these non-sacred values. In other words, social exclusion caused non-sacred values to become more like sacred values, both neurally and behaviorally.

This is a worrying finding as non-sacred values are the negotiable part of someone’s value system. The less of these there are, the more difficult it is to persuade them and, in the case of violent ideologies, the closer they move to violence. These results corroborate what we have seen in our case studies of people who joined terrorist networks. Once a person self-identified as a member or supporter of an extremist movement, it would only take a minor incident of exclusion to move them to action.

What’s likely happening here is that people, including supporters of extremist organizations, straddle many group allegiances. When they feel a rejection from one of those groups, it can cause them to double down on one of the other groups, especially if that group is antagonistic to the one that just rejected them. And this is what extremist groups want: to constrict the identity of a potential recruit so the recruit has allegiance only to them.

So what do we do with people who have fully internalized the violent ideology of a group to the point that they explicitly support terrorist groups?

To look at this, we found 30 supporters of Lashkar-e-Taiba, a Pakistani jihadist group associated with al Qaeda, who said they would be willing to carry out a violent act of jihad. When they were considering their willingness to fight and die for their sacred values, we found areas of their brains associated with deliberation and self-reflection to be deactivated. This could mean that these so-called executive functions are not being used when deciding how violently to act on their sacred values. But when we told them that their community (the broader non-radical Pakistani community) disagreed with their level of willingness to engage in violence, this caused our participants to lower their own level of violent intentions. And that decrease coincided with a reactivation of the brain areas, previously offline, associated with deliberation and self-reflection.

This suggests that a better way of engaging with devoted actors is not to attack or persuade them on the content of their sacred beliefs but rather to change their perception of what they assume their peers think are acceptable actions (aka social norms) one can take in defense of those values. These findings bring into question the effectiveness of standard public service announcements and counter-messaging that seek to change beliefs. At least as a first step, it could be better to leverage their peers’ social influence on their behavior and divert them from violent actions.

In research conducted on post-conflict Rwanda, Elizabeth Paluck has demonstrated that social norms conveyed in the media can alter behavior. Communities randomly assigned to listen to a reconciliation-themed radio soap opera over the course of a year did not change their personal beliefs about reconciliation or cooperation. Meaning, Hutus and Tutsis who did not support reconciliation a year earlier still did not endorse it. What did change was their perception of what other ingroup members valued; they now believed that other Hutus and Tutsis believed in reconciliation and cooperation.

These changes in perceptions of social norms had positive behavioral consequences on active negotiation, discussion of sensitive topics, and cooperation. For instance, the soap opera listeners had a 100% increase in comments about cooperation in follow-up focus groups, compared to control groups who were randomly assigned to listen to radio programs on health.

When Paluck ran a follow-up study in Congo and added a condition of listening to a weekly radio talk show where listeners could call in and discuss their respective grievances and viewpoints with other social groups, she found that it increased intolerance and lowered the likelihood of helping disliked community members. This suggests that, in some cases, well-meaning media programs that provide a platform for discussions on political issues could make matters worse due to the contentious nature of the conversation. These findings should also make us reflect if contentious debate programs — regularly found on CNN, MSNBC, Fox News, and the like — are detrimental to the functioning of a deliberative democracy.

We tend to pathologize people we disagree with politically and morally. We call them crazy and think there is something fundamentally wrong with their psychology. But our research shows the underlying impetus to become a devoted actor can be harnessed for good or bad. Many of us are the beneficiaries of devoted actors from the past who fought for racial and gender equality, minority rights, and individual liberties. Today devoted actors of the environmentalist movement are trying to apply pressure to divert the trajectory of a global climate crisis.

Donald Trump has created his own devoted actors by applying the same principles we find in other movements. The day after the storming of the Capitol building, he tweeted: “These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide election victory is so unceremoniously & viciously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long.” In one tweet, he summed up the key ingredients of what motivates his activist followers: a concocted threat to the sacred value of democracy and a valorization of “patriotic” devoted actors made up of people who perceive themselves to be excluded by a system that they can now violently revolt against.

In addition to security services detecting and deterring further riots, those who support Trump but not an insurrection must make their voices heard to create a strong perception of social norms that condemn violence. In the fall of 2019, the normally peaceful Catalan independence movement turned violent as some protestors turned to rioting in the wake of a court ruling that imprisoned some of their leaders involved in sedition. My colleagues Clara Pretus, Hammad Sheikh, and I ran a survey study with activists before and after the ruling. We found that those who increased their violent intentions after the court ruling were those who believed that fellow Catalans would approve of their violence. This finding further demonstrates that peaceful pro-Trump protesters have the power, and thus an obligation, to stop riots by condemning them in no uncertain terms.

In the longer term, we will have to address ways to engage with, rather than exclude, those we disagree with, especially on social media. Deplatforming extremists and conspiracists may serve a short-term security goal, but they will migrate to other forums where there will be less exposure to alternate perspectives. If their main social community becomes only those who share their view of the world, it will become very difficult to deter their actions. Maintaining social links online and offline is a first step. Engaging one-on-one, privately, in good-faith conversations, as opposed to publicly in comments sections, is another step. Understanding and addressing the specific reasons why extremists and conspiracists embraced this movement is crucial. Exposing them to information that contradicts their beliefs can be effective if it comes from sources they deem to be trustworthy, but this is becoming increasingly difficult.

Extremist and conspiracist groups dismantle trust in social institutions. Those making allegations of a stolen election, a fake news media, deep-state control of government, as well as climate-change deniers, anti-maskers, and anti-vaxxers are all increasing distrust in government, mainstream media, and scientific institutions. The more this distrust grows, the greater the number of people in society who are susceptible to the narratives of fringe groups.

Research has shown that for an organization to be deemed trustworthy, it must be perceived as possessing three qualities: competence, benevolence, and integrity. This is what malign groups seek to undermine in social institutions. A plan is needed to study and counteract this dwindling trust in order to mitigate further social fragmentation, which extremists seek to create and exploit.