“Bashar al-Assad sharmouta!” shouts Rami Jaber, delivering the punch line to his joke before the audience erupts in laughter. Pairing the former Syrian dictator’s name with the common Arabic insult — meaning “whore” — represents a bold defiance that would have been unthinkable just weeks ago. But now, the comedians of the Styria Comedy Club are seizing the moment, performing openly for crowds eager to embrace this newfound freedom.

Wherever the collective of comedians performs, the venue is packed to capacity, as I saw one Friday in early January at the Karma Cafe. This trendy spot, nestled in the northern suburbs of Damascus, hosts the troupe every Friday night. On this particular evening, the crowd is so large the show starts late. With no more seats in the main hall, some attendees sit cross-legged on the floor at the comedians’ feet. A little after 8 p.m., Omar Jayab, a 25-year-old performer, steps up to the microphone to open the evening.

“I’m very happy to be performing in front of you tonight,” he says in Arabic, before adding with a mischievous grin, “There’s even a foreign journalist in the room — probably a Mossad spy.” The quip drew roars of laughter from the audience. Switching seamlessly to fluent English, he continues, “I’m just saying you look adorable.”

For over two hours, the performance was a steady stream of laughter and applause, interrupted only by a brief 10-minute intermission.

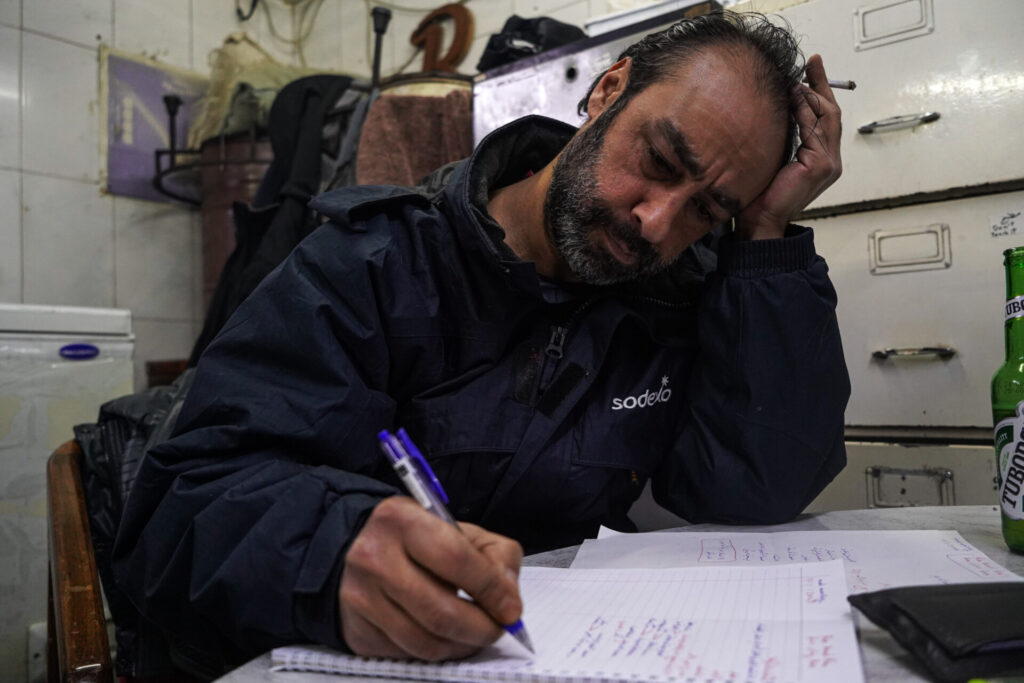

A few hours before the start of the show, Sharief Homsi is fine-tuning his set with his friend and Styria co-founder Malke Mardinali, 29, in his bedroom at his family home, just a short distance from the cafe.

The room reflects Homsi’s vibrant personality: walls adorned with Indian mandalas, an eclectic collection of hats ranging from a French beret to an Indiana Jones-style fedora, and even a Harry Potter poster he stole from the presidential palace during the regime’s downfall. It is hard to know where to look.

Since meeting three years ago, the two friends have been inseparable. At the time, Mardinali was already performing on stage while Homsi had recently returned to Syria after a few years working as a real estate agent in Dubai.

Launching a comedy club was an ambitious challenge. No one had ever attempted it in Syria before. The few comedians working in the country struggled under the weight of self-censorship and the difficulty of building a consistent audience. Even Mardinali had nearly given up in 2019.

Despite the obstacles, Styria Comedy Club was officially launched in December 2022. “At first, it was an outlet for us, but also for the Syrian people,” Homsi recalls. “Of course, we were limited back then. I mostly talked about my father, who is a dog trainer, my friends and school. Occasionally I’d slip in subtle political commentary, which terrified Malke, who was completely against it,” he adds.

When the Assad regime fell, the collective had just completed a tour of around 60 dates across Syria. “In total, we must have performed for about 9,000 people,” Homsi estimates.

“It’s certain that many officers were in the audience, monitoring us. Sometimes they’d even come up to us after the show and admit it. But even they wanted to have a good time, and we were careful about what we said,” he explains.

Just months ago, after a comedian from Styria made a simple joke comparing the names of private and public schools, Homsi found himself in serious trouble. A complaint was filed against him. The situation was only resolved when he paid $600 to have the case dropped and his name removed from a wanted list.

“Before, when we got on stage, we were afraid to tell certain jokes,” says Omar Jayab, one of the stand-up comedians in the collective. “People didn’t always dare to laugh. We all lived in fear of being sent to Sednaya,” he adds, referring to the infamous prison north of Damascus where approximately 30,000 prisoners were tortured to death or executed between 2011 and 2018.

“When we started out, we had family-friendly jokes. Out of 10 jokes I’d write, I’d only keep one. We wanted the audience to feel comfortable,” says Homsi.

Since the fall of Bashar al-Assad on Dec. 8, however, the onstage fear has vanished. Censorship has loosened its grip, and laughter flows freely.

“We feel at home here. We can laugh about anything and as much as we want — no one is watching us anymore,” says Nour, a woman in her 30s who has become a regular at the comedy club after discovering it on Instagram.

The collective spares no one, starting with the Assad family. “On the day the regime fell, Bashar sat his brother down in his office, told him to close his eyes for a surprise, and then a few hours later sang ‘Happy Birthday’ to him over video call from Moscow,” jokes Homsi, referencing the dictator’s escape to Russia on his younger brother Maher al-Assad’s birthday — without even informing him of his departure.

Even Syria’s new interim leader, Ahmad al-Sharaa, isn’t exempt from their sharp humor. Formerly a notorious jihadist, al-Sharaa made a name for himself within the Islamic State group before founding Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian branch of al Qaeda, in 2012. By 2018, he had severed ties with al Qaeda to form Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the group now ruling the country. Today, he presents himself as a polished head of state, clad in tailored suits with a meticulously groomed beard, shaking hands with diplomats from around the world.

“I wonder where it’ll end,” muses Homsi. “Is he going to turn into a hipster next or start greeting world leaders with, ‘Yo, what’s up, motherf—er?’”

“I want to test these kinds of jokes on our audience to see where the boundaries lie,” Homsi admits. “We’re still haunted by the trauma of the Assad dynasty. We tend to replace old fears with new ones.” Mardinali, however, prefers a less provocative approach, tackling politics in a more personal tone.

A minor celebrity in Syria, Mardinali shares a story on stage about an encounter with HTS fighters after the regime’s fall. He was refueling his car on the roadside when the fighters recognized him. “They stopped to take a photo, and then another car pulled up — it was CNN Turkey. They filmed me in my pajamas while the fighters sang their anthem beside me. My father, who’s very Christian, saw the footage on TV and scolded me, thinking I had joined HTS. He told me not to come home,” Mardinali recounts, leaving the audience in stitches. Even Homsi’s infectious laugh could be heard rippling through the crowd.

Each comedian has their own way of addressing the sweeping changes in the country. Throughout the night, a rotating lineup of 10 comedians performs, though the Styria collective boasts more than 20 members. Among them are Christians, Sunnis, Shiites and Druze — a diversity mirrored in the audience. Men and women, some veiled and others not, mostly young, applaud and laugh in unison.

Between sets, the evening’s host, Hussein al-Rawi, entertains the crowd with improvisations, poking fun at local stereotypes. “If we can laugh together, we can live together,” says Mardinali, summing up the spirit of the evening.

Even today, Syria’s comedy scene remains a small, tight-knit community. Comedians share modest rewards for the immense energy they pour into their performances. Still, many of them have achieved a certain level of fame in Syria. Mardinali boasts 120,000 followers on social media while 165,000 accounts follow Jaber.

“We get millions of views, but we can’t make a living from it. No one’s ever contacted me for an ad deal, except for an underwear brand. Look at my body — I’m 43! Is that really serious?” jokes Jaber. Meanwhile, Ahmad Azez, who has 215,000 social media followers, continues to practice as a dentist alongside his performances at the Styria Comedy Club and his influencer activities. He’s also launched his own perfume brand, sold in stores in Aleppo, Homs and Damascus.

From performing in a shawarma restaurant, at the Karma Cafe and even in Homsi’s family living room turned into a makeshift stage, Homsi and Mardinali are now setting their sights higher. “Before, everything was controlled. Now it’s up to us to lay the groundwork and build a sustainable economic model so other comedians can emerge across Syria,” emphasizes Mardinali.

“We’re looking for investors to open our own comedy club where people can come and laugh every night of the week,” adds Homsi.

But can one truly laugh about everything in a society still shaped by the shadow of a regime that, since Hafez al-Assad came to power in 1971, oppressed three generations of Syrians?

While the audience eagerly consumes long-repressed political jokes, the comedians are also tackling more taboo topics, such as sexuality and drug use, to challenge a society constrained by past prohibitions and traditional norms.

Just a month after Assad’s fall, jokes about the regime already feel like “old news,” according to several comedians. Even Homsi admits he sometimes grows tired of discussing the dictator. He prefers to share more personal stories — moments of life and intimacy that the audience can equally relate to.

“Humor is, first and foremost, about making people laugh. Changing the world comes second. For now, I just want to express myself, to be heard and to make people laugh,” he explains.

As the final set concludes, the door of the Karma Cafe opens, releasing a thick cloud of cigarette smoke that has built up inside. The cloud contrasts sharply with the fresh air brought by this group of comedians, determined to entertain their audience while holding a mirror up to a Syrian society that is breathing freely for the first time.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.