Among the verdant greenery and sun-dappled stelae in the gardens of Syria’s National Museum, Tareq al-Asaad, 44, wipes the sweat from his brow, sweltering in the Damascene heat. This place is a sanctum that he comes to almost weekly, surrounded by names written upon rock, inscriptions whose authors’ identities are lost to time. The gardens of the museum are full of these and other artifacts, carvings and columns.

His head is clouded with memories. Memories of a childhood and a family, of a lost home and of his father. “There used to be a picture of him hanging on this wall,” he says, smiling and pointing to a bare wall in the museum’s cafe. “I don’t know why they took it down.”

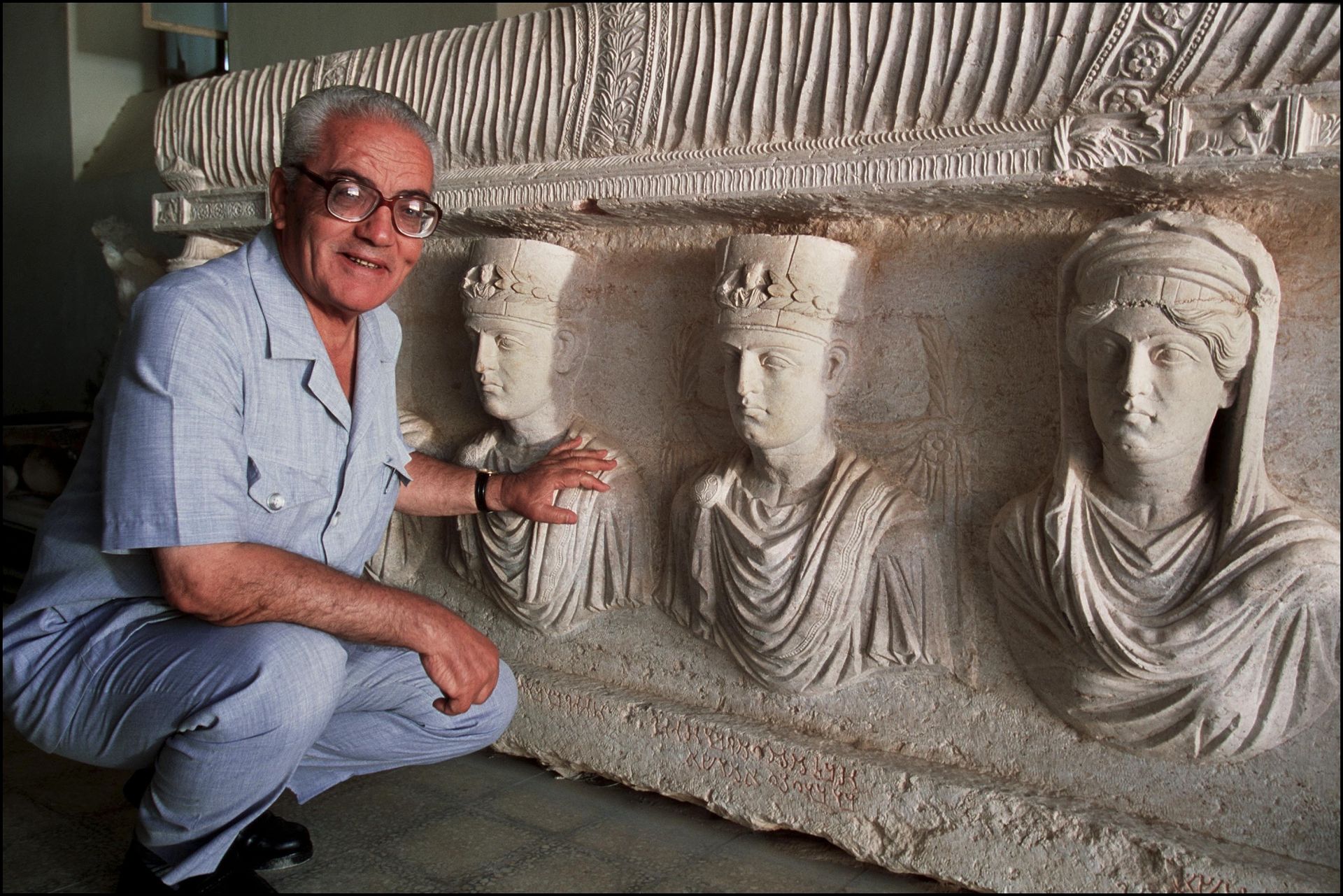

His father spent many days here; he was an archaeologist, the most renowned in Syria. His name was Khaled al-Asaad, although he had many epithets: Abu Walid, the father of Walid; the father of Palmyra; the guardian of Palmyra; the martyr of Palmyra.

He was murdered on Aug. 18, 2015, dragged into Palmyra’s main square by members of the Islamic State group and publicly decapitated in front of the town’s distraught residents.

The pain is still raw for Tareq, 10 years on. One of his eyes twitches erratically — from the stress of what he has lived through, he says. “When I speak about him, it feels like [his murder] just happened. It is as if I am small again, speaking to him, crying with him. I was the youngest, you know, he used to spoil me,” he sobs amid the hectic hustle of the busy cafe. “Over the last 13 years, they have killed us in such monstrous ways, and for what?”

Khaled was born in Palmyra, not far from the entrance to the famed Temple of Bel, in 1932. It was a remote oasis settlement cupped by the Tadmur mountains and situated at a key crossroads on the historic Silk Road. It is the site of the mythical rebel-queen Zenobia’s famed city, the ruins of which still rise from the sand and among the palms like a golden crown.

At the time of Khaled’s birth, Palmyra was just a small community of herders and farmers, living, as they had done for centuries, in small mud homes in and among the ruins of Zenobia’s great lost glory. Yet it was a community on the precipice of change. Over the preceding three years, French colonial authorities, at the behest of European archaeological institutes, had begun to resettle the residents to a “modern” town located outside the historical ruins.

Khaled grew up playing among these ruins, curiously watching these early expeditions languorously excavating small sections of the site. It was in the mists of these childhood experiences that his love for the history of his home was formed. By the age of 12, with the town lacking anything other than an elementary school, he was forced to hitch a ride in the back of a truck, bouncing his way along the as yet unpaved desert tracks to obtain an education in Damascus.

He spent years away from his home, only traveling back along those same tracks to witness the foreign expeditions that came to Palmyra every summer. Graduating with a degree in history from Damascus University in 1957, he returned to Palmyra in 1963 to become director of the recently opened Palmyra Museum — a position he held until his retirement in 2003.

“Every time he came to give a seminar in Damascus, he would reveal some new gem of knowledge that he had discovered in Palmyra,” recalls Ahmad Ferzat Taraqji, 66, the former head of excavations at Syria’s Directorate-General for Antiquities and Museums. “The heads of each department would be looking at him in amazement.”

Over his 40-year stint as director of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, Khaled oversaw the excavation and restoration of some of Palmyra’s most iconic landmarks, including the Temple of Bel, the Tetrapylon and Roman amphitheater.

Khaled “was beloved and respected” among his peers “for his professional tenacity and personal qualities,” explains Taraqji. “He was known for his generosity, always willing to help those of us more junior than him, and to host us whenever we passed through Palmyra.”

His obsession with discovering the secrets of the city of Zenobia transcended work. He was one of the few people on earth able to read ancient Palmyrene, spending hours after work in his smoke-filled study deciphering ancient texts that had been all but lost.

Much like Khaled, Khalil al-Hariri, a 65-year-old Palmyra native with a thin mustache and sallow cheeks, was spellbound by the history he grew up around. “I was always a curious youth who wanted to know everything,” he reminisces.

He used to sneak into the excavations to witness the unearthing of history. One summer, a Polish expedition came to Palmyra to undertake excavations around the Temple of Bel, but Khaled caught him and dragged him out by the ear, telling him to go back to school.

“I told him at that moment that I would be an archaeologist just like him,” he laughs. He kept that pledge. Inspired by Khaled’s dedication, he studied history, taking the mantle of director of the Palmyra Museum after Khaled’s retirement in 2003.

“We were like best friends — our relationship was a union of professional and personal spirits,” Khalil recounts. Growing up, he was essentially an unofficial member of the al-Asaad family. Khaled had five daughters and six sons — “they used to refer to me as his seventh son,” Khalil says, smiling sadly. “I remember how we used to sit around the columns of the Temple of Bel after school and study together.”

He officially joined the al-Asaad family following his marriage to Khaled’s eldest daughter Zenobia, whom Khaled named after the famed historical queen of Palmyra.

Sitting with several members of the family in an antiquely decorated home in Homs, the conversations are a patchwork of reverie, laced with historical references. Tales of Khaled intertwine with stories of the Islamic conqueror Khalid ibn al-Walid and the savageries of the Roman Emperor Aurelian. “We grew up in that museum and on those worksites,“ explains Mohammed al-Asaad, Khaled’s son. “We would rush to change out of our school uniform just so that we could go and see him at his work.”

There is a sense that Khaled, as a towering patriarch, exerted a remarkable gravitational pull on those within his orbit. Much like Khalil, six of his children followed in his footsteps by going into the fields of history and archaeology.

Yet he is simultaneously conjured in memory as a figure of gentleness and quiet modesty. “When he used to visit, he would come and sit with my young daughters and help them practice writing,” says Raslan al-Asaad, 77, Khaled’s brother-in-law. “It was unusual in that time for a man to do that — he respected all people regardless of age or status.”

It is a feeling echoed by his children. “He was like a father, a brother, a friend and a teacher, all at the same time,” remembers Tareq. “He taught us respect — respect for ourselves and him, to not drink or smoke and to work hard.”

The al-Asaad family tells a story of two halves. Each of their lives is bisected by a single day: Aug. 18, 2015.

Palmyra, like much of the country, was caught up in the euphoria of revolution in 2011 but was situated, as its historical antecedent had been, at a key crossroads between Damascus, Homs and Deir ez-Zor. By 2015, it had become a major military stronghold for Bashar al-Assad’s regime.

Yet this didn’t save Palmyra from the Islamic State’s onslaught, much like the one that had overrun Mosul a year earlier. “No one expected Palmyra to fall,” Mohammed explains, “but there was no real resistance from the regime’s forces, until Daesh [the Islamic State] got to the heart of the city.”

As the black flag of the caliphate was being raised above the municipality building, members of the family, including Khaled, Khalil, Tareq and Mohammed, gathered at the museum. The Islamic State had previously destroyed priceless relics in Nimrud in Iraq, and so it was clear what would happen to the treasures of Palmyra if they fell into their hands.

War was no novelty to them by 2015. With the group’s advance across the Iraqi border in the preceding months, they had made preparations to evacuate the museum by packing into crates as many of its treasures as possible.

“This was a fairly common practice throughout the war,” Taraqji says. He had helped evacuate museums in Deir ez-Zor and Homs ahead of rebel advances, but the speed with which the Islamic State took Palmyra surprised everyone.

Under the crack of bullets and the thud of shellfire, they rushed to pack as many of the priceless artifacts as possible into three waiting trucks. They are unsure how much they managed to save — perhaps between 2,000 and 3,000 individual pieces, according to Tareq — but no more than 40% of the museum’s collection, in Mohammed’s opinion.

Pieces too large to be moved into the trucks were left behind. The Islamic State would later release slickly edited videos of its members smashing them to pieces with sledgehammers alongside the demolition of some of the site’s most remarkable monuments, including the Temple of Bel.

During the escape, both Tareq and Khalil were injured, shot in the shoulder and leg, respectively. Under fire, members of the family clung to the back of the heavily laden trucks, packed so full there was no space inside, as they drove at high speeds down the same, now asphalted road that Khaled had hitched rides on as a child.

Khaled wasn’t with them, though. Despite attempts to persuade him, he refused to leave, staying alongside his son Walid.

Walid declined to be interviewed for this article. This tragedy is a memory he has had to relive countless times over the last decade, which I sense he sees little purpose in reopening. He did offer me a document in which he had previously written down his thoughts: “For [my father], Palmyra was the cradle of Syrian civilization and its gate to the world. He always considered her the sea from which he could not get out except dead. He would say: ‘Please, leave me here among her ruins, there have always been drops of my blood and perspiration scattered on her golden stones. I will never give up on her, I was born and lived, and I will die standing here, just like her pillars and palm trees.’”

Both Khaled and Walid were soon kidnapped by the Islamic State. Walid was released after a week, but Khaled was kept for a month, tortured and interrogated in a cellar under the Zenobia Hotel, owned by the al-Asaad family.

According to Walid, they were looking for “the hidden gold of Zenobia,” which of course did not exist. Khaled’s dream was to discover just a single statue depicting the mythical queen. The only surviving depiction of her is a single small bronze coin stashed away in Damascus’ National Museum.

Then, on Aug. 18, Islamic State militants forced the residents of Palmyra to gather in the town square at gunpoint, where Khaled was brought and decapitated. His headless body was crucified, his head placed at his feet, still wearing his iconic thick-rimmed glasses, at a site not far from the place of his birth by the gates to the Temple of Bel. His head and body were buried separately in secret at night. They have still not been recovered.

The members of his family who had escaped Palmyra had gathered in Homs because rumors had reached them that Khaled was about to be released. “It was a shock, it shattered us,” Tareq laments. “This war broke everyone.”

There is a shadow that hangs around the family now, as if some lighthouse that helped guide them through their lives has gone out.

Like so many in Syria, their home is gone and the family is dispersed. Walid went to France, plagued by health issues following his detention by the Islamic State. Others have fled abroad, to France and England. Part of the family is in Damascus, others are in Homs. No one remains in Palmyra anymore.

They don’t see each other that often. Those days in the spring of youth, chasing each other through the golden ruins in the Palmyrene desert and playing football with visiting archaeologists, have faded, preserved only in old photographs and wistful anecdotes.

Tareq hasn’t seen Walid for 11 years. His only wish these days is to be granted a visa to go and visit him. “When [my father] died, it broke something in our family,” he sighs. “We lost him and our home, and then when our mother died in 2020, it felt as if the glue holding us together had dissolved.” Khalil had always “felt like he was part of the family when [Khaled] was there,” but he now feels that something changed after the family became separated.

He still visits Palmyra but paints a picture of a town abandoned and destitute. Mines still remain across the desert, and places that had once been a source of adventure now instill fear. The museum remains closed; no one has been appointed to run it since Khalil retired in 2021. The city of Zenobia has been mutilated, and little work has been undertaken to restore the historical city that Khaled gave his life to a decade ago.

The desecration of Palmyra never really ended. After the regime recaptured Palmyra in 2017, the looting of its treasures only worsened — reaching its height under the rapacious mandate of Malik Habib, Assad’s military intelligence chief in Palmyra. Tareq was imprisoned on three occasions for speaking out publicly about the regime’s systematic plundering of Syrian artifacts.

There are no commemorations for the anniversary of his death. His story is not well known in Syria — just a single drop in the suffocating sea of tragedy. His family was shattered like many others, his home and his city were destroyed like the rest.

Khaled’s family says his love for Palmyra was rooted in a firm belief that it represents the shared heritage of mankind. A small solace is that Khaled’s name is now indelibly etched into the history of Palmyra. His story, his sacrifice, is part of our shared heritage. He will always be the father of Palmyra.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.