There were half a dozen garbage dumpsters standing at attention by the side of the road in al-Bass, an industrial district of Tyre in southern Lebanon, a few minutes from the city’s 3,000-year-old Iron Age necropolis, where Jesus is said to have once sat down for a picnic.

This was our first bus terminal of the day.

The war that has been going on for the better part of two years was at a decrescendo — sort of. To this day, Israel still drops bombs on seemingly random homes and vehicles across southern Lebanon, picking off civilians and alleged Hezbollah members almost every day. June brought, frighteningly, a two-week war between Iran and Israel that spurred nervous jokes about World War III and an imminent nuclear apocalypse. In Lebanon, where I live, my colleague João Sousa and I watched the long-range Iranian missiles fly over us en route to Israel, in a sort of ballistic Wimbledon.

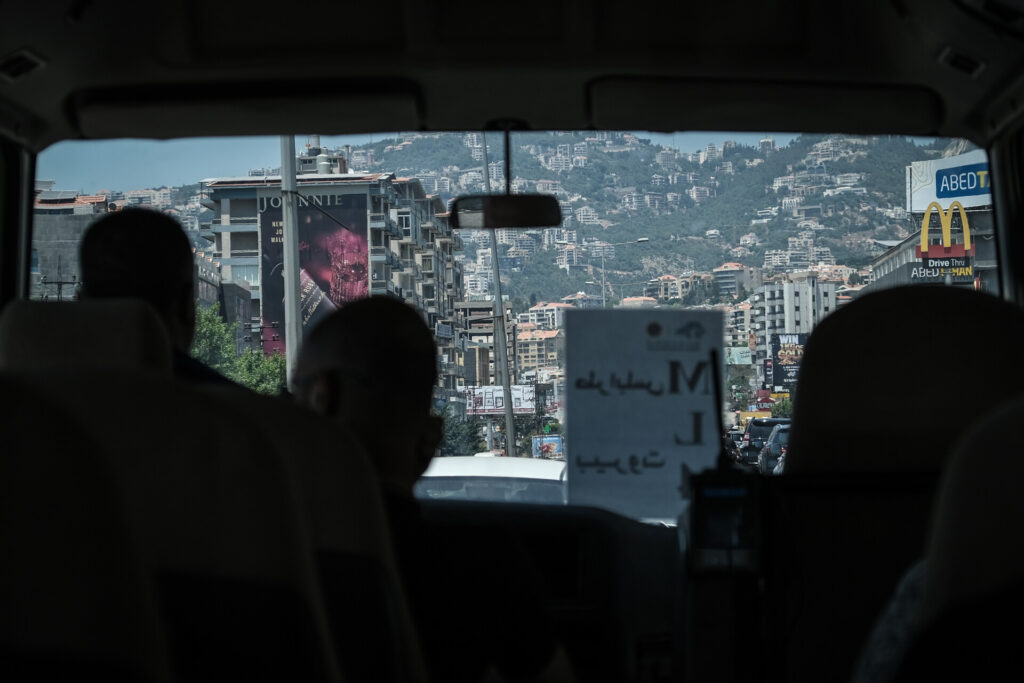

Still, it was summer, and it was time to dream small. At our little bus stop in Tyre, that meant finally trying out Lebanon’s first new public bus system in decades, the deep purple buses bearing the Arabic words “al-naql al-mushtarak” and, in English, “public transportation.” As of June, the purple buses now crisscross Beirut and stretch the roughly 130-mile length of the country, from beach- and bomb-ridden Tyre in the south to industrial Tripoli up north.

I figured João and I could make the trip in a day.

A previous attempt at state-organized transit, back in 2022, saw France donate a modest 50 buses to Lebanon’s Railways and Public Transport Authority. But the project panted to a sad halt in a matter of weeks amid a lack of funding and a workers’ strike over pitifully low wages.

The timing was bad. Lebanon was already in the midst of a financial crisis that, since 2019, had decimated tens of thousands of people’s life savings and plunged the Lebanese pound to previously unexplored depths. Then, in 2023, came war with Israel, which expanded from the south to the whole of Lebanon in September 2024. A million people fled their homes in the hardest-hit zones, which included Tyre. More than 4,000 people were killed. Simply leaving the house meant checking for the latest bomb “warnings” issued by the Israeli army via, of all platforms, X.

There was little space to dream about nice buses.

Lebanon is tiny. I Googled it to make sure: According to thetruesize.com, a map website that measures such things, it fits neatly into the toe of Italy’s boot. If Lebanon is so small, why is it so hard to connect its parts by bus?

“Actually, there is public transport,” Tammam Nakkash, a civil engineer who specializes in urban planning and transportation, told me.

That is, there’s a whole nerve system of informal, privately run bus and van routes already pulsing through the country. The most famous of them is the storied No. 4 line, whose dozens of haggard white vans span the breadth of Beirut, from the working-class Dahiyeh suburb to Hamra. I’ve ridden the line alongside everyone from ancient Sudanese cooks to young claw-clipped Lebanese women, purses in lap, heading home from work. In their off hours, the No. 4 vans sleep in Laylaki, in Dahiyeh, where I recently found a stray one parked under a friend’s apartment building near some uncleared rubble from an Israeli airstrike. Magazines and even entire novels have been written about the No. 4, whose passenger chitchat and nicotine-fueled road rage “reflect the reality of the social, political, and religious ‘line’ the van travels in the past, present, and future,” according to one academic publication.

Good luck finding a timetable, though, or disability access. Or official bus route maps. Or stops.

It’s shambolic, but “it helps by offering a service when nothing else existed,” according to Hala Younes, an architect. She set up an installation earlier this year at Beit Beirut, a house museum along the city’s former civil war-era front line, mapping the country’s informal bus routes. There, I found little veins of colored light hugging the contours of a giant topographical map, marking where Lebanon’s informal buses carry their passengers.

“‘Informal’ is a wrong term,” Rami Semaan, a civil engineer, insists. He’s worked on public transit since the end of the Lebanese Civil War, which lasted from 1975 to 1990, when movement around the then-fractured country meant crossing deadly front lines. To him, “informal” seems to imply those grassroots-level van and bus lines are themselves, somehow, at fault, when really the government should be doing more to regulate them.

“Politicians in Lebanon prefer roads, which are easier. … They don’t like public transport because this means more social interaction between people and more independence,” Semaan posits. “Citizens will depend on the public [transit] system,” rather than political clientelism a la Lebanon’s sectarian “zaim” bosses.

Still, the existing/informal bus system has its problems — decrepit vehicles, sometimes mafia-esque bus owners and few options for people with disabilities. Once, while I was on a swelteringly hot van ride from Tripoli to Beirut last year, the doors of the trunk suddenly broke free on the open highway, spilling suitcases and unfurling a fluffy swirl of polyester blankets across the asphalt. More importantly, “there is a lot of harassment,” Hala adds, “especially for young women and girls. I wouldn’t like to have my daughter take those buses.”

That could be changing. A public tender last summer saw Ahdab Commuting & Trading Company (ACTC), a logistics group in Tripoli headquartered just a few doors down from the city’s Ottoman-era clock tower, win a contract to handle Lebanon’s public transit — including those 50 dormant French buses. The proposed bus network would go on to cover not only Beirut and its suburbs but also lines to Tyre, Tripoli and Chtoura in the Bekaa Valley (a hub for onward sojourns to Syria).

The new buses now allow for cashless payment with prepaid cards and, in some cases, digital screens tracking the bus routes in real time. It would all be acronymed, rather confusingly, ACTCPT. I still just go with some variation of “the purple buses.”

The official launch of the purple buses could not have been timed worse — the ceremony came just days before Sept. 23, 2024, when Israel began to expand its deadly bombing campaign across Lebanon into a so-called “66-Day War.”

The purple buses would not truly start catching on until months later, after a November ceasefire brought a fragile peace to most of Lebanon.

We were five minutes outside Tyre, then 10, and 20. Green banana orchards slid past, then a United Nations peacekeeping armored vehicle and a recently planted billboard about the dangers of landmines.

About a dozen people hopped on and off the huge city-size bus along the road north to Sidon. Muhammad and Nour, an elderly Syrian couple from Deir ez-Zor, were off to do their weekly shopping. Ghassan al-Ali, a middle-aged Lebanese man visiting home from Denmark for the summer, was headed to Sidon to take pictures of the sea castle. Young baseball-capped workers stepped on then off again amid the coastal groves and car-tire depots. A nurse in blue scrubs rode just a few minutes to a clinic.

Muhammad and Nour were in their 60s. They told me that, yes, they had heard of the new public buses, mostly that they were cheaper than the existing informal network, the equivalent of about $1.50 for a ride ending in Beirut.

But when I asked why they were on board today, they gave me confused looks. They simply hadn’t questioned the fact that this was the first bus to have passed by as they waited together on the side of the road, for whatever might show up. It was how they had always traveled Lebanon’s highways.

Somewhere in the rows behind them, two off-duty Lebanese army soldiers in camo laughed at each other’s jokes, on the first leg of a long journey home to Akkar, in the farthest northern reaches of the country.

We reached Sidon’s main Nijmeh Square, lined with buses, vans and little shared taxis, known as “services” (pronounced as in French).

Two of the van drivers there said they paid a monthly pittance to “some guy” who lets them use their spot in the roundabout as a makeshift bus stop. In exchange, Mr. Some Guy manages a sort of timetable for them. They told me they’re worried about the cheaper purple buses taking away some business, at least for now, with the price of gasoline being so high.

Across the roundabout, ancient bus drivers ashed cigarettes into paper espresso cups inside a decaying bus terminal. The latter belonged, apparently, to a private transit company still running the decades-old buses stationed outside. I didn’t see any passengers climb on board.

Behind the old service desk, an attendant told us not to take pictures, and then promptly disappeared into the traffic circle among the carts selling “kaak” bread and men smoking cigarettes.

We waited for the next purple bus inside, away from the heat, beneath a crumpled old map of Lebanon on the wall.

Samira Kharma was born in Msaitbeh, Beirut, 81 years ago, one of 13 children. Back then, a two-line streetcar network first built in Ottoman times still crossed the city, its teeny wooden cars snaking along metal tracks that, in some places, still poke through the asphalt.

On some days, all 13 of them would board the Beirut streetcar together. Sometimes, they’d go to the downtown souks, where her father had a butcher shop. At times, she’d hold her gaggle of younger siblings’ hands, helping keep them in order inside the tiny streetcar. In those days, a ride was 10 cents per seat.

“We used to hear a lot of Armenian being spoken,” she remembered, and other languages, too, from the sorts of people who intermixed in Beirut — Lebanese-accented Arabic, and English.

It was on one of those streetcar trips to the souk as a young woman that she bought the fabric for her wedding dress. It was later stolen, she told me at her home in Beirut, “during the war.”

“Everyone in Beirut used the tramway,” 73-year-old Muhammad Amin told me from his home not far from Samira’s. He remembers riding the streetcar as a boy, after dropping out of school, to work as a car painter or sometimes to visit his grandmother. Other times, he did it simply to enjoy being outside the house.

“Beirut was prettier then, and there weren’t as many cars,” not like today’s traffic-clogged streets.

By the late 1960s, the streetcar network had been dismantled, as “service” taxis and American cars became more popular. It was a system that would come to favor private car dependency over public transit, choking side streets and highways alike with all manner of sedans and SUVs.

“Before that, nobody had cars,” Muhammad remembered. “Only rich people.” A car painter with little money, he’d go on to take rickety buses, or simply walk, for hours.

“We’re missing out now, without the tramway,” said Marwan Zahour, founder of Beirut Heritage, a history society with a page that sometimes posts old photos of the city and its streetcars. He, too, once rode them to work as a young man, to his job as a clerk at the Beirut Municipality. “We miss out on beautiful things,” he said. “Like riding to the sea.”

There are also, simply, the lost moments of sitting together with all types of Beirutis. According to Hala, the architect, “Public transport is not only some place where people meet, but also a way for us to deal with the fact of everyone living together in a crowded city.”

Where they mix the most is, apparently, the Cola Roundabout.

There, as in Nijmeh Square in Sidon, buses and vans wait in the heat to collect passersby, announcing trips to Chtoura, Aley, Tripoli and the south. Sellers of falafel and tissue paper wander the traffic circle, under a bridge caked in soot. Men in purple vests matching the purple buses sit waiting for their scheduled drives to start; others, from the privately run buses, simply stand outside, shouting the name of their destination in a sort of musical rhythm. In a way, it’s a well-oiled machine.

A dozen or so screens covered the wall of one room in ACTC’s sleek concrete office block in Anfeh, a short ride from the entrance to Tripoli. We paused here, just ahead of our final stop in Lebanon’s “bride of the north.”

Inside were three young employees in purple vests, watching a live feed of the buses moving through their mapped routes. To date, there are 11 routes and just under 100 buses. They have up to 5,000 riders per day, give or take, but “our goal is to cover all of Lebanon,” Hoda Ahdab, head of branding, told me. Her brother, Aoni, is ACTC’s CEO. Their grandfather first founded the family transit business in Tripoli in the 1960s.

Cola Roundabout was on the screen, plus all the other little streets where the bus icons inched along.

The team is hoping to launch a live-tracker app for riders within a few months, likely with help from the huge microwave satellite on the roof of the Anfeh office, which triangulates each bus’s location — including whether the drivers go off-route. Apparently, I was told, this sometimes happens when drivers get impatient in traffic.

There are even AI-assisted security cameras pointed at the drivers and bus carriages, sending little alarm sounds to the HQ room if, for example, a driver lights up a cigarette mid-journey.

That is what happened about a minute later, when an alarm went off, bringing up a live video feed of a bus driver somewhere in Beirut taking puffs of, I imagine, a pack of Cedars. “Please don’t do that, sir,” Nur Hayek, the operations manager, told him, gently, through a desk-mounted mic.

They both smiled a bit sheepishly, hiding a guilty laugh, testing out the perimeters of an anti-smoking rule that is brand-new to the vast majority of Lebanese bus drivers.

Finally, in Tripoli, we found ourselves disembarking in the city’s historic al-Tall Square. We were just steps from the old Fahim coffeehouse, where, as I searched at the last minute for stories of the bygone days of Lebanon’s public transit, I was told there would be elderly folks wiling away the hours.

There I found Narja Salim, 80, originally from Alexandria, Egypt. She came to Lebanon decades ago, she said, after marrying a Lebanese man from Tripoli. She sat alone in the cafe courtyard, taking demure drags of an “argileh” water pipe amid the fallen leaves.

I asked her if she had any memories of the Beirut streetcars, stopped and dismantled back in those last years before the civil war. She rarely goes down to Beirut, instead living out her years here in Tripoli.

She responded in the present tense, marveling at what she called Beirut’s “metro,” as if she had never heard the news that Beirut’s streetcars stopped running back in the 1960s — before 15 years of war, before a historic economic crisis, a port explosion and yet more war that made a streetcar in Lebanon feel like a distant dream.

She still had a sliver of a memory of riding the streetcar, to a passport appointment at the Egyptian Embassy in Beirut. “It was so beautiful,” Narja smiled.

I was too saddened by the prospect of shattering her illusion of Beirut as a glittering city by the sea, complete with its own metro. Maybe I should have corrected her. I didn’t.

It was time for the last purple bus of the day, from Tripoli. On a street corner outside ACTC’s old office, near the Ottoman clock tower, the bus waited as a hodgepodge of people filed in. They all told me this was the first time they had heard of the new public bus system at all.

As with Muhammad and Nour, the Syrian couple in the banana fields of Tyre, this bus in downtown Tripoli was simply the first one they had encountered on their hunt for a ride to wherever they were headed. It wasn’t particularly clear that this was the terminal for the purple buses, any more than that the other nearby patches of busy sidewalk were also makeshift bus stops for the informal vans and buses, hoping to pack in enough of the surrounding humanity to break even on the drive down to Beirut.

There was a young man bedazzled with colorful rings, who said he was here from Beirut simply to get his argileh pipe repaired. A pair of young Syrian brothers from Aleppo told me they were hoping to make their return flight to Germany via Beirut tomorrow — if the trip wasn’t canceled by the ongoing tennis match of overhead missiles.

The sun slipped behind the sea. We were headed back south along the coast, past an army checkpoint and rows of car dealerships, past beach resorts and cemetery headstone showrooms.

On X, I was told of a new barrage of huge missiles on their way from Iran to hit somewhere near Haifa. We were still here beneath the warheads’ path, riding in an air-conditioned French bus equipped with AI-assisted security cameras, (sort of) unscathed, for now.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.