The Netflix series “The Eternaut” has been a global success. The streaming service never discloses viewership figures, so we’re left to infer impact from its advertising campaigns. In Argentina, the show has sparked widespread conversation about an imagined alien invasion in Buenos Aires, praise for local actors and admiration for the production’s technical polish — its staging, storytelling and special effects.

Perhaps this was just further validation of the stereotype that Argentines are narcissistic. Though we did see, on YouTube, a short clip — one of the opening scenes — in which the protagonists play truco, a distinctly local card game where banter, jokes and provocations are part of the ritual. The dialogue turns to the weather — rain and thunder — and unfolds through a series of crude, sexually charged puns that defy translation. Still, YouTube offers the scene in English, Italian, German, Czech, French, Hindi, Hungarian, Indonesian, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese, Thai, Turkish and Ukrainian.

We can explain its success in Argentina. As for how it’s interpreted elsewhere, we can only speculate.

“The Eternaut” is a masterpiece of Argentine popular literature for many reasons — reasons that have boosted its readership into the millions. Among them is its place within a constellation of texts conceived and produced on the margins of the literary system. As Argentine critic Juan Sasturain notes, these texts are marginal in relation to the canon, yet transformed into classics by their readers.

Three other works belong decisively to this lineage: the poem “Martín Fierro” by José Hernández, written in 1872 as if sung by a gaucho; the chronicle “Operación Masacre” by Rodolfo Walsh, a denunciation of the execution of Peronist militants, published in 1957, the same year “The Eternaut” began, and considered the foundation of the nonfiction narrative form some years before Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood”; and the comic strip “Mafalda,” a satire in the “costumbrista” tradition of observing everyday life, by the cartoonist Quino, published between 1964 and 1973.

None of these were produced as literature per se, yet all three (along with “The Eternaut”) became literary classics. Their weight in the collective memory and cultural annals of Argentina is immense. That’s why the audience for “The Eternaut” approached the series with anticipation: We all wanted to know what they were going to do with our comic strip.

But “The Eternaut” is also a politically resonant text. As is well known, Héctor Oesterheld, its writer, was kidnapped and disappeared by the Argentine military dictatorship in 1977, along with his four daughters and their husbands. Only one of his grandchildren survived; two others were disappeared by the regime and remain missing. With the return of democracy in 1983, his work was swiftly recovered, and numerous tributes followed. In 2000, the comic was reissued as part of a collection of Argentine literary classics, at the suggestion of the renowned literary critic and writer Ricardo Piglia. In 2010, the Argentine parliament declared Sept. 4 National Comic Book Day, in honor of the publication date of the first chapter of “The Eternaut” in Hora Cero Semanal, a magazine also created by Oesterheld.

But none of this appears in the series — not a mention, not even a hint. There is no reference whatsoever to the 1976-1983 dictatorship. Perhaps the screenwriters assumed it was common knowledge, a kind of historical backdrop that didn’t need explaining. In contrast, the original comic strip, published between 1957 and 1959, sets the action in the then-futuristic year of 1963, a time when the dictatorship wasn’t even imaginable, though political violence had already begun to simmer in Argentina.

The series, however, relocates the action to 2001, during a real and devastating economic and political crisis. This historical setting helps contextualize certain behaviors, such as the street protests in the opening scene. At the same time, the 2025 release of the series has reopened public debate in Argentina around the disappeared and, in particular, the kidnapped children, including Oesterheld’s own grandchildren.

As I said, all of this formed part of the local expectations — among readers, fans or simply those familiar with the comic. It doesn’t explain why the series resonated with those who are unfamiliar with it.

The relationship between cinema and literature is as old as cinema itself. Historical accounts suggest that many of Georges Méliès’ films, completed between 1899 and 1910, were adaptations from literary works, drawing from Shakespeare, Lewis Carroll, Mary Shelley and Jules Verne. I imagine that, at the time, few questioned the quality of these adaptations. After all, “quality” can mean many things: from reverence for the original and fidelity to it, to new forms of expression enabled — or compelled — by the shift in medium. Back then, the sheer novelty of the moving image was enough to captivate audiences. Moreover, a few minutes of footage could hardly be compared to works whose reading demanded far more time and attention.

A few months ago, in a review of another Netflix adaptation — this time of Gabriel García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude” — Santiago Ospina Celis used a familiar word to describe such relationships: betrayal. The betrayals he cited were numerous and not limited to the adaptation itself. They included, for instance, the sale of García Márquez’s archive to the University of Texas and the posthumous publication of his final novel against his wishes.

Inevitably, all adaptations are a betrayal of language, even when the original authors collaborate with the screenwriters — in which case, they betray themselves. The shift from literature to film entails a radical change in language: from words to moving images. Among other consequences, this means that what our imagination once conjured is now replaced by what the image dictates. Perhaps the only viable conclusion is the one Ospina Celis attributes to García Márquez: “I have seen many great films based on very bad novels, but I have never seen a great film based on a great novel.” Yet considering that Gabo himself wrote the screenplay for a 1964 film adaptation of the great Mexican writer Juan Rulfo’s novella “El Gallo de Oro” (“The Golden Rooster”), this may not be a conclusion at all — but, rather, a false trail.

“The Eternaut” is not a novel, but what Argentines call a “historieta” (comic strip), originally written by Oesterheld and drawn by Francisco Solano López, and published weekly between 1957 and 1959. Had it been released 20 years later, we would likely have called it a graphic novel.

In essence, it is a story told through images, typically the result of collaboration between a writer and an illustrator. This collaborative format somewhat reduces the potential for betrayal: If a film adheres reasonably closely to the visual narrative, the transition from comic to screen tends to provoke less scandal or controversy — though it still involves a transformation of language, as the images begin to move. From the many iterations of Superman and Batman to the sprawling Marvel dynasty, we know that controversy is inevitable. Discussion of the gap between the original 1938 Superman and James Gunn’s recent version could easily fill hundreds of pages — and perhaps even a doctoral thesis in cultural studies.

But Netflix’s “The Eternaut,” in that sense, is peculiar: It is “The Eternaut” as filmed by Bruno Stagnaro for Netflix, not “The Eternaut” conceived by Oesterheld and Solano López. Its “betrayal” is radical, beginning with its visual choices. The original comic is in black and white and adheres strictly to the traditional strip format — three panels per page, rarely broken. There are no visual explosions; the artwork supports the narrative with restraint and reverence.

This contrast is especially striking in the way Buenos Aires is treated as a central character in the show. The city bursts onto the screen — not just as a backdrop, but as a charged setting. Before the snowfall that marks the start of the alien invasion, it’s alive with street protests, traffic chaos, heat and noise. And once the invasion is underway, the city becomes a dynamic space of movement and tension. Buenos Aires is not merely a set; it’s a space saturated with meaning.

The betrayal also operates at the level of plot. It begins with the very first scene, a moment that comic book readers remember vividly and one that is crucial to understanding the entire story. In the original, the protagonist of the adventure, Juan Salvo, appears one night before a comic book writer — Oesterheld himself — and begins recounting the tale of an alien invasion that will take place in the future, knowledge he possesses because he is traveling through time. This narrative choice establishes the comic’s structure: an omniscient first-person account. Salvo tells his story to a writer who simply transcribes it. That first-person voice disappears in the series. Salvo is, literally, an eternaut — the name he gives himself — a navigator of eternity, moving through time and thus able to foresee what lies ahead.

In the series, however, the opening scene features three young women on a boat, two of whom die from a toxic snowfall (a few episodes later, we learn that the sole survivor is Salvo’s daughter). In short, there is no eternaut. Across all six episodes, there is no reference to the title’s meaning. The eternaut is simply a masked man — his mask, we later learn, protects him from the toxic snow — but we are never told where that enigmatic name comes from. Or at least not in the first season, where there are only hints that Salvo’s relationship with time is more complex than it seems.

This may well be the greatest achievement of the series: radical betrayal. Stagnaro freely constructs a new narrative, anchored in two enduring motifs and enriched by a host of innovations. The invasion and the snowfall are the two organizing principles that shape everything that follows. From this foundation, Stagnaro rewrites the story with complete creative license, while still preserving a wealth of references that are indispensable to readers and connoisseurs of the original text.

The wager is clear: Netflix does not invest in an expensive, sprawling production merely to validate the memories of a few million readers familiar with the source material. Even so, that is not a negligible figure, so the goal is to offer a new global commodity for these millions to consume. And this commodity comes with the hallmarks of Netflix’s global packaging: As with “One Hundred Years of Solitude” or “Pedro Páramo,” these are Latin American works that captivate precisely because of their Latin American identity, not despite it.

Of course, “The Eternaut” is not regarded as a literary work on the same level as the others, and it operates within a different register of meaning. The former works belong to the core aesthetic of so-called magical realism, which never found an equivalent in Argentina, where literature has long been shaped by the cultural weight of Buenos Aires and its ties to European traditions, with the work of Jorge Luis Borges as its apex.

What sets “The Eternaut” apart is its ability to relocate a narrative invented and traditionally staged in the Global North — an alien invasion — and render it in the peripheral Global South with rigor, creativity and plausibility. The apocalypse unfolds in the realistic Buenos Aires of “The Eternaut,” not in a fabricated setting like the one used for Marvin J. Chomsky and Faye Dunaway’s “Evita Perón” (1981), lamentably filmed in Guadalajara.

The alien invasion, of course, is not a Netflix or Stagnaro invention. Neither is it Oesterheld’s. It likely first appeared in H. G. Wells’ “The War of the Worlds” in 1897 (another text adapted for film), and it exploded in 1950s American mass culture as a metaphor for the Cold War. The threat wasn’t Martians or Venusians — it was Russians. What made Oesterheld’s comic strip radically new was, as Sasturain puts it, “the home of adventure.” Oesterheld had already spent years scripting adventure, war and intergalactic comics, often featuring American protagonists, like war correspondent Ernie Pike in World War II or Sergeant Kirk of the 7th Cavalry in the American West. Both were illustrated by Italian artist Hugo Pratt, who was then based in Buenos Aires. But “The Eternaut” unfolds entirely in Buenos Aires in 1963 — an imaginary time six years after it was written and drawn — with precise geographical references, especially to the northern edge of the city and its suburbs, stretching to the River Plate stadium and the Barrancas de Belgrano park.

Here, I should offer an apology: For fans of the original, the stadium reference may be a spoiler. All of us who read the comic are eagerly awaiting that confrontation, which we’ve been told will take place two years from now, when the next season will be released.

And then, of course, there’s the toxic snowfall. For Argentine readers, its novelty is doubly radical: The snow is toxic — a chilling invention by Oesterheld — but it is also snow in a city where snowfall occurred only once throughout the entire 20th century, and then just once more in the 21st.

The series has been a monumental success, achieving unprecedented viewership for an Argentine production, even in the realm of streaming. I could offer a long list of reasons for its local popularity, which include, but are not limited to, the morbid impulse to compare it with the original. Without exaggeration, “The Eternaut” is one of the great works of Argentine popular literature, and its countless reprints make it entirely plausible that its readership is in the millions, spanning at least three generations. I’ll return to this point, because it has led to a very contemporary form of political appropriation.

But I believe the key to its international success lies not so much in the freedom or quality with which Stagnaro rewrites the basic premise of the alien invasion, but in his fidelity to certain crucial elements of the original. Chief among them is that the hero does not precede the story but is born within it — an ordinary man thrust into a crossroads of destiny who senses that this moment, precisely, marks a turning point in his life.

What is exceptional is not the hero but the situation that transforms him. The adventure may shift its setting, as I mentioned earlier, because it is the place where an ordinary man encounters his fate. And that can happen on a battlefield in Germany, on a snow-covered street in Buenos Aires or, if need be, in Addis Ababa. But Oesterheld introduced — and the series both respects and expands — a key element of local culture: Argentina’s rich tradition of disseminating technical knowledge among the middle and working classes.

By 1957, Argentina was a semi-industrialized country, with a significant number of students attending technical schools. But even earlier, starting some 40 years before, there had been a widespread diffusion of such knowledge, with publications like “Popular Mechanics” following the American do-it-yourself model. That tradition, brilliantly analyzed by Beatriz Sarlo in her 1992 book “La Imaginación Técnica” (“The Technical Imagination”), is embodied in the character of Alfredo Favalli, who can repair — or even invent — virtually any device for fighting the aliens.

To this core, Stagnaro adds another clever layer: In Salvo, there is a memory of real war that draws him back into combat — specifically, the 1982 war over the Falkland Islands (also known as Islas Malvinas) between Argentina and the United Kingdom. This conflict occurred not only after the original comic’s publication, but also after Oesterheld’s death at the hands of the dictatorship. This history adds a specific layer of meaning. The 1982 war is framed primarily as a nightmare in Argentine culture, which remembers it as a war that should never have happened. It is because of it, though, that Favalli is a technician while Salvo handles weapons with ease.

One of Stagnaro’s most notable innovations in the series is the introduction of female characters — powerful women who are entirely absent from the original comic. Simply put, in 1957, almost no one could imagine women fighting battles, let alone against aliens.

Stagnaro also honors another of Oesterheld’s core ideas: He follows the characters and their transformations attentively and tenderly. Salvo, like Favalli or Lucas, gradually becomes a hero through the course of the adventure, without knowing it and without ever seeking to be one. The clearest case of transformation is that of Omar, a character whose fear turns him into a fleeing coward, but whose action transforms him into a committed and compassionate fighter. The same applies to Inga, who operates on two fronts: as a female migrant (a Venezuelan) and as a member of the popular classes. In this, Stagnaro follows Oesterheld, who discovers his characters (all of them from the middle and popular classes) as he writes them over the course of two years, in a story structured as a serial. Each episode ends with a “To be continued,” without fully revealing where the characters will be by the time the adventure concludes.

Stagnaro recreates that sense of accompaniment, though he knows exactly where he’s headed: toward the battle against the aliens, who have yet to appear. The beetles that do show up early on, as we know, are merely cannon fodder. What the series reveals is the creation of a collective hero in motion. That’s why the slogan accompanying its release in Argentina is “No one is saved alone.”

In the original comic strip, the extraordinary occurs twice: First, an ordinary man finds himself in an exceptional situation and becomes a hero. Then, he encounters another ordinary man, a comic book writer, and turns him into a witness to the extraordinary by recounting his story, so that the writer can, in turn, tell it to us — a perfect mechanism of nested Chinese boxes. But the third movement is the collective one, and it’s the series’s most powerful element. The extraordinary event gradually gives rise to a series of exceptional individuals, men and women pulled from their everyday lives to do one thing and one thing only: save the world.

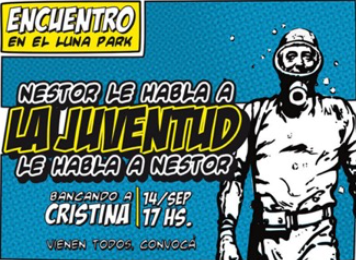

Oesterheld’s biography, which portrays him as a political activist who gradually aligned with the Peronist left, led to his appropriation by the government of Néstor Kirchner, who ruled from 2003 to 2015 — and even to the use of the former president’s image in that controversial transformation:

The face inside the mask was no longer that of Salvo or of the actor Ricardo Darín, but that of Kirchner, transformed into the Nestornaut, without anyone ever offering a convincing reason for the association. In short, it rests on the assumption that Oesterheld and Kirchner were politically aligned. Yet this claim is highly questionable; it is doubtful that Kirchnerism can be regarded as a modern incarnation of the Peronist left. That association resurfaced with the success of the series, standing in stark contrast to the far-right government of Javier Milei, which openly rejects any notion of collective heroism, favoring radical individualism and selfishness. Of course, the idea of “The Eternaut” as a political metaphor can be stretched too far, for the series resists linear and, frankly, reductive interpretations.

Far more compelling as iconography is the tribute poster published by Sasturain in 1984 in the magazine Feriado Nacional, which offered a concrete demand for justice in the face of the kidnapping and disappearance of an artist.

A copy of that poster hung on the wall of my house until it was abducted by an alien invasion. Or by a divorce — I can’t remember which came first.

“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers twice a week. Sign up here.