“Spotlight” is a newsletter about underreported cultural trends and news from around the world, emailed to subscribers every Monday and Wednesday. Sign up here.

Last week, a member of Tunisia’s National Guard went on a shooting spree outside a synagogue on the island of Djerba, where hundreds of Jews from across North Africa, Europe, North America and Israel had gathered for an annual pilgrimage. Four people, including two pilgrims, died in the attack.

But before the shooting occurred, the El Ghriba synagogue was holding one of the most raucous, joyous festivals in the country — a celebration of nearly 3,000 years of community and connection to the island. The American photographer Skyler Dahan, who has Moroccan Jewish roots, had flown to Tunisia to document the pilgrimage to El Ghriba after visiting the synagogue once years earlier. In a conversation with New Lines, he shared what he saw and experienced before the shooting — and what he feared could be lost if antisemitic violence kept people away from the pilgrimage.

“Are you Jewish?” the armed guard at the checkpoint leading up to El Ghriba asked Dahan when he arrived for the first of a two-day celebration. “It was a weird moment, when you’re being asked that question in an Arab country,” he said, but something about the tight controls felt comforting, a buffer against the outside world.

“There were rows of military men in white hats and gloves who looked like they were there to greet a president,” he said. Then there were armed security forces, checkpoints, metal detectors, layers upon layers of security for a site so old and symbolic that it is said to house a stone — or perhaps it is a door — salvaged from the Temple of Solomon.

Whether the legends are true or not, El Ghriba is, most likely, the oldest synagogue in Africa (the other contender is deep in Libya and has likely been destroyed in recent conflict). Built by a community of Amazigh Jews, it dates to the 6th century BCE and is one of the oldest continuous sites of worship in Judaism.

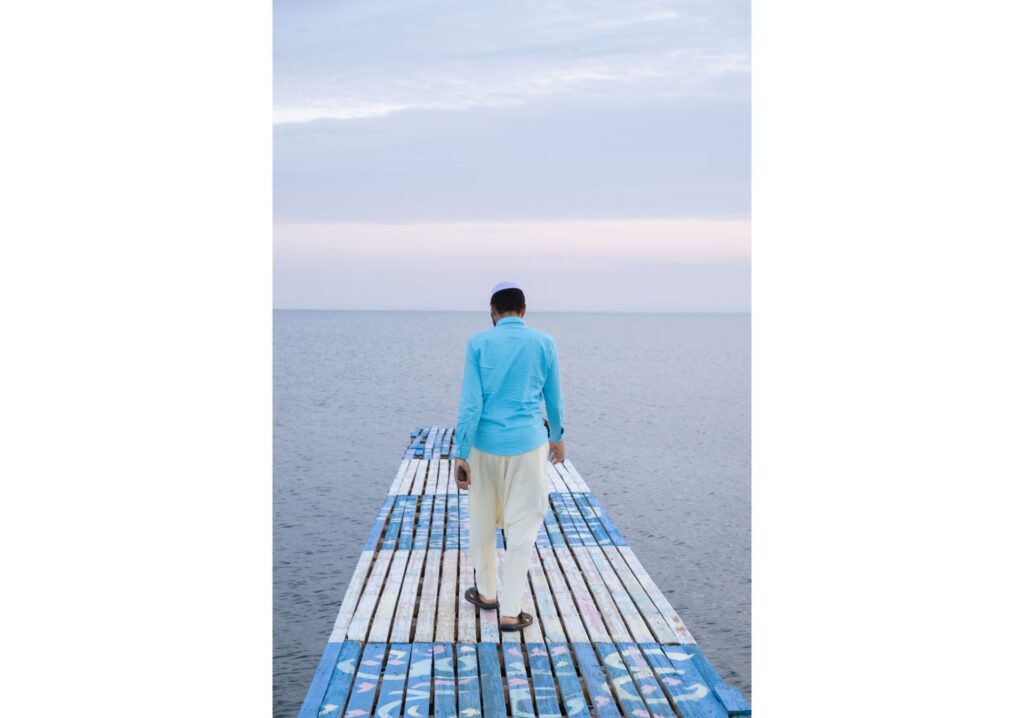

The Jewish community on Djerba has dwindled since the 1950s, when many of Tunisia’s Jews emigrated to France or Israel. But the synagogue on the desert island has remained a gathering place. Each year for the minor holiday of Lag BaOmer, Tunisian and other North African Jews from throughout the diaspora flock to Djerba — not to celebrate a religious ritual so much as to celebrate the reunion of their community.

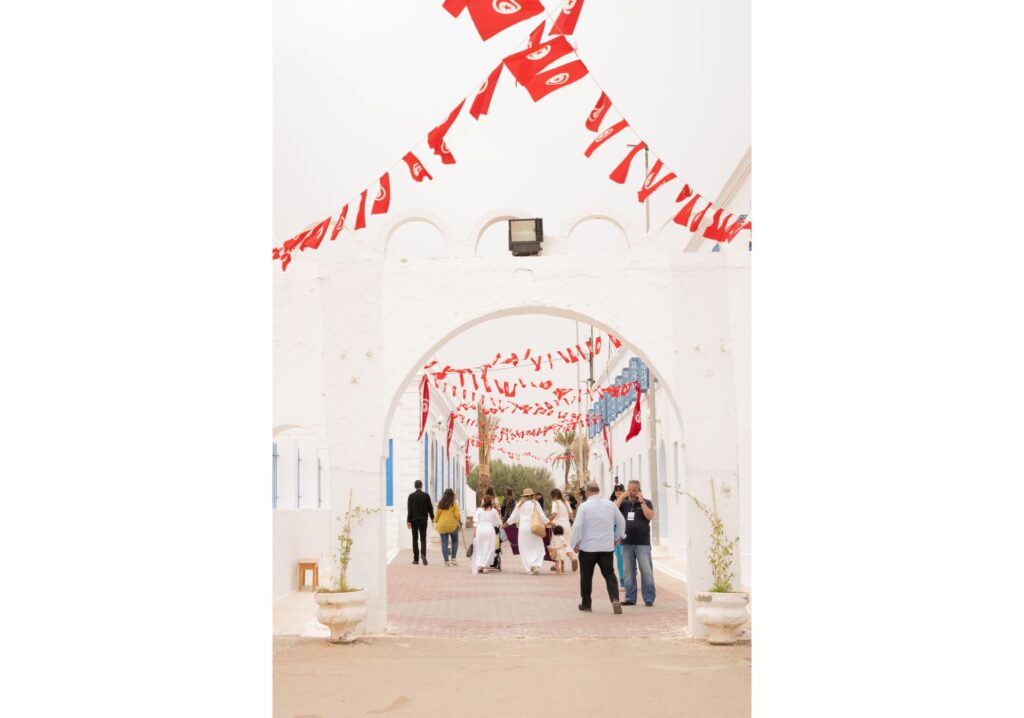

Once through security, Dahan squeezed in between revelers who were packed into the courtyard like the sweet sardines fished just off Djerba’s shores. Swathes of bunting of Tunisian flags were strung from the upper floors. “Everyone was drinking. Everyone was dancing,” as music — sung in Judeo-Arabic — boomed from the stage set in their midst, Dahan said. There were swirls of color and glints of light off of gold and silver jewelry, their tintinnabulation adding to the din of the music.

The fashion and personalities were as varied as they were numerous: older women wrapped in traditional white Tunisian safseris; other older women dressed for a weekend in St. Tropez; a family that looked straight out of a trailer for “Real Housewives of Miami Beach”; men chomping cigars, holding court, greeting friends with abundant kisses and a firm shake of the shoulders after an embrace.

From the kitchen, a miasma of unctuous smells lured in revelers for refreshment, mostly in the form of brik — a shatteringly thin fried pastry shell filled with a silky, barely cooked egg, tuna, capers and potatoes. Brik after brik was turned out from great pans of oil, while massive pots of chraime, a slow-simmered fish stew made by Djerban Jews for the Sabbath, bubbled away on the back burners in preparation for the evening meal.

As Dahan wove his way through the crowd and into the sanctuary, the riotous atmosphere shifted. There, a solemnity prevailed as pilgrims lit candles — hundreds of candles, with wax dripping everywhere, sticking to fingers and dripping on shoes — as they prayed in Hebrew but with an Arabic accent. Women wrote wishes and blessings on eggs that were placed in a small grotto, heeding a superstition that has grown along with the pilgrimage.

Dahan left the synagogue a few hours before the gunman opened fire outside the complex, killing two pilgrims and two police officers. The news shook him; he said he felt a pang of both fear and grief — and a concern for the future of the pilgrimage and the community that gathered there.

“Seeing that connection, that community, was really transformational,” Dahan said. “If this doesn’t survive, you’d be losing a part of something incredibly important” — a living legacy of one of Tunisia’s oldest and most vibrant communities.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our stories in your inbox.